Neil McAleer is probably best known in these pages for his fine biography Visionary: The Odyssey of Arthur C. Clarke (Clarke Project, 2012), but this is just one of his titles. In fact, his book The Omni Space Almanac won the 1988 Robert S. Ball Award from the Aviation and Space Writers Association, and his work has appeared in magazines from Discover to the Smithsonian’s Air & Space and in many newspapers. A recent note from Neil reminded me that August 25th marked one year since the death of Neil Armstrong. This reminiscence of the astronaut brings Armstrong wonderfully to mind and gives us a bit more of Clarke, leaving me to wonder only how time has gone by so quickly in the days since the death of both men. McAleer’s article also gives me a chance to pause in Starship Congress coverage as I begin to collect papers from many of the presenters, the first of which we’ll be looking at a bit later this week.

by Neil McAleer

From the great deep to the great deep he goes.

— Alfred Lord Tennyson

The first letter I ever received from Neil A. Armstrong was dated May 21, 1987. Earlier that month, I had sent his office a copy of my recently published The OMNI Space Almanac with the hope he would agree to read and verify its text covering the final descent and landing on the moon of the Apollo 11 mission.

I had no clue if he would respond to my request or not, but it was worth a try. When I saw Lebanon, Ohio, on his return address a few weeks later, I was thrilled to have his reply — whatever it said. He thanked me for the book and wrote:

“I have been overwhelmed with business obligations this past several months, and have not yet had the chance to read it carefully.

“I will give my comments when the pressure subsides.”

Of course, I was all but certain that his pressure would never subside, but I was very grateful for his words.

That letter was my bonding with Armstrong for life, and it began a small friendship that lasted over 21 years and was sustained through occasional letters, emails, and phone conversations, several of which were interviews for my various works in progress.

Five months after receiving that special letter, in October 1987, I published a piece in Space World, “The Space Age Turns 30,” for which I interviewed 26 astronauts, science fiction and science writers, and various other space experts, asking them where they were when Sputnik 1 was launched — the event that would forever mark the beginning of planet Earth’s space age. Among the astronauts I interviewed for this piece were all three Apollo 11 crew members: Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins.

Here is the published text that was distilled from the Armstrong interview that took place in the summer months of 1987.

“You know, going back 25 years or more and trying to remember something accurately is dangerous. I think many people remember what they remember rather than what happened.

“My recollection is that I was at the Society of Experimental Test Pilots symposium at Los Angeles at the time. The SETP symposium is always in the fall, about the time of the World Series. And I believe that to be true because I remember that it caused the Society some consternation at its inability to get press coverage, when every journalist was concentrating on Sputnik.

“I was flying various projects at Edwards Air Force Base at the time, including the X-15. [Its first flight took place post-Sputnik, in June 1959.] Those of us at Edwards High Speed Flight Station were working on projects we thought might lead eventually to spaceflight, so I’m certain that Sputnik was of extreme interest and concern to all of us in that business. What it came down to was: The Russians had one and we didn’t. We got one and then went on to the Moon.”

Those last two short sentences let us into the mind and heart Armstrong — the core of the man — as few short phrases can: Cut to the essence; cut to the action; take over the manual controls to land successfully on the moon! It demonstrates the truth of the succinct phrase describing him in his high school yearbook: “He thinks, he acts,’tis done.”

Image: Neil Armstrong as I (PG) like to remember him, a laser-focused professional at the top of his game.

Neil and I had two more informal project interviews, with follow-up correspondence, for works in process. One interview took place on March 16, 1989, which was part of my research for my first Arthur C. Clarke biography, originally published in 1992. The second focused on Neil Armstrong himself, a 1994 piece in the Baltimore Sun (“Neil Armstrong, Reluctant Hero”) that celebrated the 25th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing, and the exemplary character of its commander, Neil A. Armstrong.

This piece was primarily my research, but I sent a draft to Neil and followed up with a phone call. My intent here was to make sure there were no egregious or even minor errors, which I knew he would tell me about if they appeared. Armstrong’s reach for excellence was ever-present.

My memory tells me that the last phone conversation/interview we had was for this Baltimore Sun piece in the spring of 1994, but there were a few email exchanges during the rest of the 1990s and into the first decade of the 21st century.

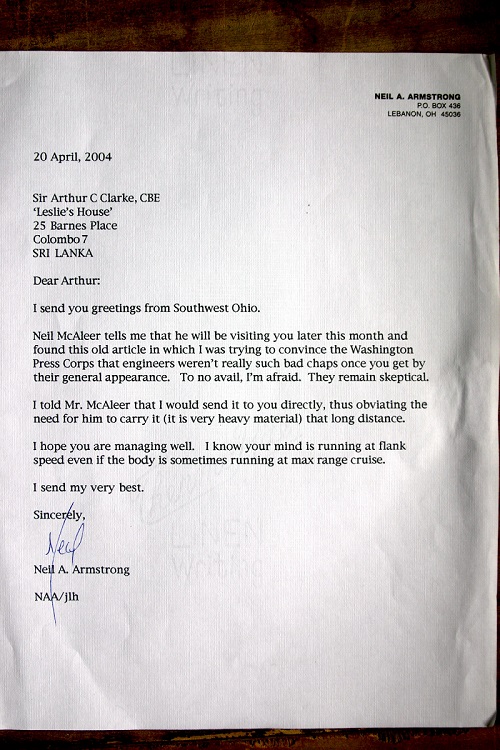

I was completely unaware of the last letter from Neil Armstrong that I played a part in. It wasn’t until I visited Arthur Clarke at his home in Colombo Sri Lanka, for the first time in April-May 2004 that I learned about it and read the original there.

Before my trip I wrote Neil to tell him I was making the long voyage over. It would be the first and last time I saw Arthur Clarke in his native habitat, where he chose to live in the 1950s. I was seeking a few special “gifts” to bring Arthur. Neil had said this about Clarke in a speech at the National Press Club in February of 2000:

“For three decades I have enjoyed the work and friendship of Arthur Clarke, a prolific science and science fiction writer, who back in 1945 first suggested the possibility of the communications satellite. In addition to writing some wonderful books, he has also proposed a few memorable laws. Clarke’s third law seems particularly apt today: Any sufficiently developed technology is indistinguishable from magic. Truly, it has been a magical century.”

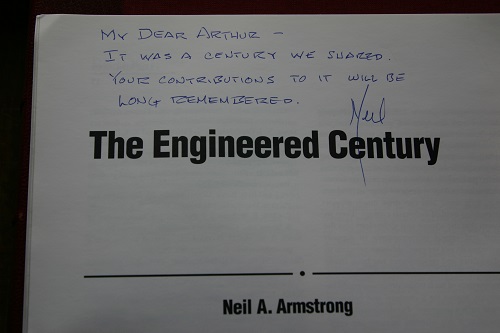

My letter to Neil, dated April 10, 2004, read in part: “I’m taking a brand spanking ‘new’ copy of ‘The Engineered Century’ piece from The Bridge* in Spring 2000 to Sri Lanka with me to give to Arthur as a gift… Would it be possible for you to sign and date a copy to him on the first page of your piece?” (This was after Neil Armstrong had put a moratorium on requests for his signatures. “Unless I sign the wet concrete of a building cornerstone, and it can’t be carried away,” he told me once.)

* A quarterly magazine, issued by the National Academy of Engineers. This article was an edited version of a speech Armstrong delivered at the National Press Club, 22 February 2000.

Neil’s answer came back the next day: “I will be happy to help out as you have suggested. I will mail the book directly to Arthur to save you the trouble of carting it to Sri Lanka.”

After arriving at Clarke’s home and office in Colombo in late April, I asked Arthur if a package had arrived from Neil Armstrong. “Yes,” he said. “The inscribed Bridge and a letter.”

The letter was a complete surprise to me—and much more significant than an accompanying note.

It was the best letter written by Neil Armstrong that I had ever seen because it was a personal one to Clarke, who at 87 years was having multiple medical issues, including memory loss. And Armstrong’s humor and personality came through clearly in his words.

So two gifts had been sent to Arthur by Neil Armstrong: the inscribed magazine that was a cooperative initiative between the two of us; and his wonderful letter to Arthur—now in the Clarke archives. A photograph of that letter is below.

And here is Neil’s article with inscription to Clarke:

There was a brief email exchange between us in mid-October 2005. I happened to see an obituary in the New York Times of a fellow test pilot that he may have missed, so I forwarded it on. I first sent this with a brief personal note attached to his office via the NY Times email forward, but apparently it never arrived. So I sent it again, “in a more straightforward manner,” and he replied a few days later:

“Thank you for the obit on George Watkins. Although I get the Times, I did not see the article. I didn’t know George well, but he came to Edwards on a number of occasions when I was working there.”

The fact that he replied at all to such an off-the-cuff brief forward was indicative of Neil’s warmth and generosity. But I was especially happy about the consistent use of abbreviated greetings and signature closings that framed this round of emails: I had headed mine: Neil A. from Neil M., and he replied with: Neil M. from Neil A. He accepted the usage. And he kept his message short: “‘Tis done.”

Our last emails were sent during 2008, the year that Arthur C. Clarke died at the age of 90 (March 19). Several months later, not long after Neil celebrated his 78th birthday on August 5, I brought him up to date and sent him a link to the last professional photographs of Clarke taken shortly before he died. That was our final communication—some 21 years after I received Neil’s first letter.

I never met Neil Armstrong face to face, but I knew him through his own words and voice, and our small friendship was life-changing for me. In the 1980s, our occasional interactions renewed and invigorated my natural propensity for optimism that had slowly gone into hibernation during my forties.

I’ve always thought of Neil when looking at the moon—ever since he and Buzz and Mike flew there and back, not quite a half century ago. Like countless admirers around the planet, I too grieved last August, reluctant to give up the hope that he had many more good years left. I genuinely thought Neil would be with us for the 50th Anniversary of Apollo 11 in 2019—and I take great comfort in the fact that his life story and giant spirit will always be with us.

In the years leading up to the Apollo missions and perhaps during the mission years too, the astronauts were apparently willing participants on a roster, answering letters from the public, often in all likelihood written by youngsters such as myself. When the time came for my letter to be answered, just prior to the Apollo 11, who drew my straw but Neil A. Armstrong. Encouraging words and best wishes were signed off by hand, rather than on an auto pen. Understand your thoughts on bonding Neil. For those interested, the text read:

‘Dear David:

Thank you very much for your nice letter of congratulations. It always pleases me to hear from enthusiastic young people such as yourself who have such a keen interest in our activities.

Our recent flights have been all that we could hope for and we are encouraged to believe that we can reach our goal.

Again, thanks for writing and best of luck to you.’

Well, I’ve certainly enjoyed good luck! Further, my brilliant mother, at the post office and about to post my letter, carefully opened it and had it copied and so, I have that still too.

Thanks Neil and Neil!

I never met Mr. Armstrong but my family and I were fortunate enough to be there when Apollo 11 launched, I can still remember the incredibly loud roar of the rockets from where we were. Back then the future seemed so amazing and without limits. All due to men like Mr. Armstrong!

I’ve always thought we should expand the Apollo legacy with a serious effort to build a colony on the moon. And now we have a 3D dust printing scheme, and continuing indications of water.

http://arstechnica.com/science/2013/03/giant-nasa-spider-robots-could-3d-print-lunar-base/

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/08/130827091355.htm

As I have written here before I spent nearly 2 years with Neil and Buzz during the Apollo Era.

Besides being ace test pilots , I think , they were the only crew who could give a technical lecture , chalk talk, about the mathematical process of manual orbital rendezvous.

Not that the other crews didn’t have good astrodynamics smarts , but they were exceptional. It would be a while before the astronaut corps had any others like them.

I can only think of one anecdote I have never related.

One day at the Lunar Module Simulator Neil stepped out while waiting on a reboot of the simulator, sat in a chair and smoked a cigarette.

He said: “Well… that was my one smoke for this year.”

(In those days it was not unusual for some of the astronauts to smoke, goodness Ed Mitchell was a chain smoker, but many did not, at least I did see them do it at work. A bit surprising because it was absolutely forbidden to smoke in the CM or LM cockpit. Would have thought all would have given it up.)

Different times.

Just in case people missed this (from a year ago, of course):

http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/michael-collins-the-neil-armstrong-i-knew–and-flew-with/2012/09/12/b3f7556c-fb7c-11e1-8adc-499661afe377_story.html

ALES FROM THE LUNAR MODULE GUIDANCE COMPUTER

Don Eyles

(A paper presented to the 27th annual Guidance and Control

Conference of the American Astronautical Society (AAS), in

Breckenridge, Colorado on February 6, 2004, and designated

AAS 04-064. This version includes additional illustrations and

comments, and several minor corrections.)

ABSTRACT: The Apollo 11 mission succeeded in landing on the moon despite two computer-related problems that affected the Lunar Module during the powered descent. An uncorrected problem in the rendezvous radar interface stole approximately 13% of the computer’s duty cycle, resulting in five program alarms and software restarts.

In a less well-known problem, caused by erroneous data, the thrust of the LM’s descent engine fluctuated wildly because the throttle control algorithm was only marginally stable. The explanation of these problems provides an opportunity to describe the operating system of the Apollo flight computers and the lunar landing guidance software.

Full paper here:

http://www.doneyles.com/LM/Tales.html

Apollo 8: humanity’s first voyage to the Moon

As China returns to the Moon this month, the US remembers the anniversary of another major milestone in lunar exploration. Anthony Young recounts the first crewed mission to orbit the Moon, which launched 45 years ago this week.

Monday, December 16, 2013

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2421/1

The Sculpture on the Moon

Scandals and conflicts obscured one of the most extraordinary achievements of the Space Age.

By Corey S. Powell and Laurie Gwen Shapiro

One crisp March morning in 1969, artist Paul van Hoeydonck was visiting his Manhattan gallery when he stumbled into the middle of a startling conversation. Louise Tolliver Deutschman, the gallery’s director, was making an energetic pitch to Dick Waddell, the owner.

“Why don’t we put a sculpture of Paul’s on the moon,” she insisted. Before Waddell could reply, van Hoeydonck inserted himself into the exchange: “Are you completely nuts? How would we even do it?”

Deutschman stood her ground. “I don’t know,” she replied, “but I’ll figure out a way.”

She did.

At 12:18 a.m. Greenwich Mean Time on Aug. 2, 1971, Commander David Scott of Apollo 15 placed a 3 1/2-inch-tall aluminum sculpture onto the dusty surface of a small crater near his parked lunar rover. At that moment the moon transformed from an airless ball of rock into the largest exhibition space in the known universe. Scott regarded the moment as tribute to the heroic astronauts and cosmonauts who had given their lives in the space race. Van Hoeydonck was thrilled that his art was pointing the way to a human destiny beyond Earth and expected that he would soon be “bigger than Picasso.”

In reality, van Hoeydonck’s lunar sculpture, called Fallen Astronaut, inspired not celebration but scandal. Within three years, Waddell’s gallery had gone bankrupt. Scott was hounded by a congressional investigation and left NASA on shaky terms. Van Hoeydonck, accused of profiteering from the public space program, retreated to a modest career in his native Belgium. Now both in their 80s, Scott and van Hoeydonck still see themselves unfairly maligned in blogs and Wikipedia pages—to the extent that Fallen Astronaut is remembered at all.

“The most romantic place on Earth is Cape Kennedy.” – Paul van Hoeydonck

And yet, the spirit of Fallen Astronaut is more relevant today than ever. Google is promoting a $30 million prize for private adventurers to send robots to the moon in the next few years; companies such as SpaceX and Virgin Galactic are creating a new for-profit infrastructure of human spaceflight; and David Scott is grooming Brown University undergrads to become the next generation of cosmic adventurers.

Governments come and go, public sentiment waxes and wanes, but the dream of reaching to the stars lives on. Fallen Astronaut does, too, hanging eternally 238,000 miles above our heads. Here, for the first time, we tell the full, tangled tale behind one of the smallest yet most extraordinary achievements of the Space Age.

Full article here:

http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2013/12/sculpture_on_the_moon_paul_van_hoeydonck_s_fallen_astronaut.html

By Deborah Byrd in

BLOGS | VIDEOS | HUMAN WORLD | SPACE on Dec 20, 2013

Video: New earthrise visualization lets you experience it

Earthrise via Apollo 8 astronauts in 1968

A new visualization of events leading to one of the iconic photographs of the 20th century – Earth rising over the moon.

To mark the 45th anniversary of the famous Apollo 8 “Earthrise” photograph, NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio today (December 20, 2013) released a new visualization of the events leading up to the photo’s capture. The video gives you a front row seat on the view seen by lunar astronauts in the Apollo 8 mission, as, during a roll maneuver of their craft, they peered from a window and noticed Earth ascending over the lunar horizon. You are there, as they capture one of the iconic photos of the 20th century – Earth rising over the moon.

Full article and video here:

http://earthsky.org/space/apollo-8-earthrise-december-24-1968-new-simulation

‘There Is A Santa Claus’ – The Voyage of Apollo 8: Part 2

By Ben Evans

Forty-five years ago, on 21 December 1968, three men were launched atop the most powerful rocket ever brought to operational status—the Saturn V—to begin a mission more adventurous, more audacious, more challenging, and far more dangerous than had ever been attempted in two million years of human evolution. As described in yesterday’s history article, Apollo 8 astronauts Frank Borman, Jim Lovell, and Bill Anders roared away from their Home Planet and re-lit the third stage of their launch vehicle in an event somewhat innocuously described as ‘Trans-Lunar Injection’ (TLI). That six-minute firing propelled them out of Earth’s gravitational clutches for the first time in history and set them on course to visit our closest celestial neighbor, the Moon.

Strangely, in the hours after TLI, none of the men could see much of the Moon at all. It was barely a crescent from their perspective and they would not really see it in its entirety until they arrived in orbit around it on Christmas Eve. “I saw it several times in the optics as I was doing some sightings,” admitted Lovell, but “by and large, the body that we were rendezvousing with—that was coming from one direction as we were going to another—we never saw…and we took it on faith that the Moon would be there, which says quite a bit for ground control.” As they headed towards their target, Apollo 8 slowly rotated on its axis in a so-called “barbecue roll”, to even out thermal extremes of blistering heat and frigid cold across its metallic surfaces.

One hundred and forty thousand miles from Earth, and 31 hours after launch, the astronauts began their first live telecast from the mysterious “cislunar” environment, betwist Earth and the Moon. Borman had tried to have the camera removed from the mission, but had been overruled, and now found himself using it to film Lovell in the command module’s lower equipment bay, preparing a chocolate pudding for dessert. Next there was a shot of Bill Anders, twirling his weightless toothbrush. “This transmission,” Borman commenced for his terrestrial audience, “is coming to you approximately halfway between the Moon and the Earth. We have about less than 40 hours to go to the Moon…I certainly wish we could show you the Earth. Very, very beautiful.”

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=28284

Articles on the 45th anniversary of Apollo 9, the mission that tested the Apollo CSM and LM in Earth orbit in 1969 and conducted the only EVA during an Apollo mission while circling our planet – among other space firsts on the road to Luna:

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2462/1

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=31834

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=31841

Did you know the ascent stage of the LM named Spider stayed in Earth orbit until 1981 due to a six-minute firing of its engine?

It is also a shame that Rusty Schweickart’s bout with space sickness as it is often called apparently cost him future space missions, thanks to the macho attitude of the astronaut corps then. At least he did go on to do other important things with space, some of which may even save ourselves some day:

http://themittani.com/features/interview-b612-foundation