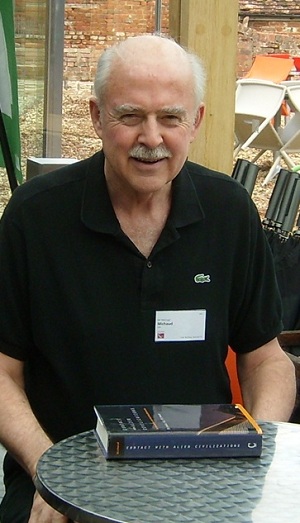

Diplomat and author Michael Michaud returns to Centauri Dreams with a look at interstellar probes and how we might use them. Drawn from a presentation originally intended for the 100 Year Starship Symposium in Houston, the essay asks what effect our exploring another stellar system would have on its possible inhabitants. And beyond that, what effect would it have on us, as we weigh ethical issues and ponder the potential — and dangers — of highly intelligent artifacts going out into the galaxy? Michaud is the author of the indispensable Contact with Alien Civilizations: Our Hopes and Fears about Encountering Extraterrestrials (Springer, 2007). Among his numerous other works are many on space exploration. He was a U.S. Foreign Service Officer for 32 years, serving as Counselor for Science, Technology and Environment at the U.S. embassies in Paris and Tokyo, and Director of the State Department’s Office of Advanced Technology. He has also been chairman of working groups at the International Academy of Astronautics on SETI issues.

by Michael A. G. Michaud

Although the planets may belong to organic life, the real masters of the universe may be machines. We creatures of flesh and blood are transitional forms.

— Arthur C. Clarke

A Paradigm Reversed

For the past forty years, nearly all published work about the impact of contact with an extraterrestrial civilization has foreseen that it will be one way, from the aliens to us. These scenarios have rested on an assumption that any alien civilization detectable by its technological activity must be more scientifically and technologically advanced than we are.

The 100 Year Starship Study is bringing this paradigm into question, because of an anticipated change in human capabilities. We are talking about sending our own machines to visit nearby star and planet systems. This is the beginning of a role reversal.

We could be the first technological civilization to begin expanding its presence into this region of the galaxy. The impact of contact, whether intended or not, might flow from us to others.

If there are alien forms of intelligence in any of the target systems, they may be less scientifically and technologically advanced than we are. If those other sapient beings live in pre-industrial societies, they may not be detectable before our probe arrives.

On Earth, practical ethics imply that we should try to anticipate the effects of our actions. Our plans for our probe’s arrival in an alien system should have an ethical dimension.

Sending Out a Mind

Our first interstellar probe may include the most autonomous artificial intelligence we have built up to that time. While much of its behavior will be pre-programmed, the probe’s actions may not be determined solely by the instructions it receives from its makers. That probe must be able to adapt to unforeseen circumstances, in some cases to make its own decisions. How independent should that intelligence be?

During its long journey, such a machine might evolve by connecting data in new ways. The artificial intelligence could be mutated by the effects of radiation generated when the probe collides with interstellar matter.

An altered machine might make choices different from those its senders intended. Like the HAL 9000 in 2001: A Space Odyssey, the probe might override its programming, making its own choices about which actions it will take.

It may take years for our new instructions to reach the probe. It would take more years to know if the probe has obeyed those instructions.

Robot Warriors

We are seeing a preview of this issue in the military use of robots. Articles in Scientific American have warned of a threat from semiautonomous machines over which humans retain nothing more than last-ditch veto power. Some systems are only a software upgrade away from fully self-sufficient operation.

According to articles in The Economist, humans will increasingly monitor military robots rather than fully control them. Some robot weapons already operate without human supervision to save precious seconds. Defense planners are considering whether a drone aircraft should be able to fire a weapon based on its own analysis.

As autonomous machines become smarter and more widespread, they are bound to end up making life or death decisions in unpredictable situations, thus assuming – or at least appearing to assume – moral agency.

The Singularity

We have heard much about a Singularity predicted for less than twenty years in our future. At that time, human intelligences would be uploaded into machines, eventually becoming independent of biology.

Our interstellar probes could be the most advanced forms of such an uploaded intelligence. Sending out such intelligent machines could be a first step toward a post-biological galaxy.

A Second Singularity may begin when we lose control of the probe. The good news is that we would be sending our creation very far away, where it would pose the least potential risk to Humankind.

Recognizing Evidence

We commonly assume that our probe will give priority attention to whatever planet in the target system is most like Earth. What will our probe look for? High on that list will be evidence of life.

With a limited payload, interstellar probe designers will have to make choices among instruments. Those choices will rest on assumptions about the nature of life that prevail at that time.

Will the probe recognize evidence of life forms very different from the ones we know on Earth? What if the probe reports ambiguous evidence? What if we are not sure whether the phenomenon we discover is life or non-life, because it is so different from the life we know?

Even if forms of life exist on that far off world, the probe’s sensors might not detect them. A report that there are no signs of biology could clear the way for an eventual human colonizing mission.

Will the probe also look for evidence of intelligence? Will it recognize such evidence in a society that does not emit electromagnetic signals and does not pollute its atmosphere with the by-products of industry?

Should our probe send signals to whatever planets it observes? Would local intelligences be able to receive such messages, or understand them?

It is conceivable, though not probable, that our astronomers will remotely detect signs of intelligent life in a nearby system before we launch a probe. Should we send a probe to that destination, or avoid it?

The Consequences of Contact: A Mirror Image

What would be the impact on intelligent beings who detected our probe? How would they react? This could be seen as a mirror image of the debate among humans about the consequences of contact for us.

What if the extraterrestrials had believed that they were the universe’s only intelligent beings, as most humans have believed about themselves? What if an alien technological civilization had used astronomical instruments to survey planets around other stars as we are doing now, and had found no evidence of the kind of biochemistry they know? They might have concluded that they were alone.

Even if they had imagined life and intelligence on faraway planets, they may not have thought of interstellar exploration. They may not have anticipated direct contact. Our probe’s arrival in their system could be a startling surprise.

Detecting evidence of an alien technology in their system would tell them that at least one civilization had achieved interstellar flight. They would know that contact could be direct.

To extraterrestrials, we would be the powerful and mysterious aliens, whose character and purposes are unknown. Suddenly, they might feel vulnerable.

Alien impressions of Humankind would be determined by their understanding of our probe. What would they see as our motivation in sending it? Would they think that the detected probe was only one of many, part of a grand scheme of relentless interstellar colonization?

Consider what now seems the most likely form of such an encounter: a fly-through of the alien system. The probe’s high velocity would make the event brief. Our machine might not be detected. If it were, the extraterrestrial equivalent of skeptical scientists might say that a one-time sighting is not proof.

Arthur Clarke described such a scenario in his novel Rendezvous with Rama, in which a giant alien spacecraft flies through our solar system without stopping or communicating. The implied message was deflating: Humankind was not only technologically inferior, but also irrelevant.

Imposing Ethics on a Machine

We humans have set a precedent for regulating our behavior toward possible alien life during our interplanetary explorations. Protocols are in place to avoid contaminating other solar system bodies, and to prevent back-contamination of the Earth.

Implicitly, we have accepted a principle of non-interference with alien biology. Such rules may be extended to an interstellar probe, suggesting that our machine should not enter the atmosphere or land on the surface of a planet suspected to have life.

What should be our probe’s rules of engagement if it encounters intelligent life? Will our machine be able to make ethical choices? Can we give our probe a conscience? Should our probe obey Star Trek‘s often violated Prime Directive, observing the other civilization while keeping our presence secret?

Before Star Trek, Stephen Dole and Isaac Asimov argued that contacts with alien intelligence should be made most circumspectly, not only as insurance against unknown factors but also to avoid any disruptive effects on the local population produced by encountering a vastly different cultural system. After prolonged study, a decision would have to be made whether to make overt contact or to depart without giving the inhabitants any evidence of our visit.

Image: The Hubble view in the direction of Sagittarius, looking toward the center of the Milky Way. The discovery of life around distant worlds raises huge questions of ethics and even self-preservation as we ponder what kinds of future probes we might send. What should a program of galactic expansion look like? Credit: NASA, ESA, K. Sahu (STScI) and the SWEEPS science team.

Future Behavior

Some of those involved in the extraterrestrial intelligence debate have assumed that a program of sending probes, once begun, would continue until all the Galaxy had been explored, perhaps by having probes reproduce themselves. This model has been used to dismiss the idea of extrasolar intelligences; if we don’t see their machines, they must not exist.

This model flies in the face of the only behavioral data base we humans have: our own history. No human expansion has continued unchecked. No technological program continues indefinitely.

Newman-and Sagan argued that self-reproducing probes will never be built because they constitute a potential threat to their builders as well as to other sentient species that encounter them. Wise civilizations would not create potential Berserkers.

What if we send several probes, and none finds a habitable planet? Would our interstellar probe program be abandoned like the Apollo manned missions to the Moon? Sending our first probes might be a technological catharsis, not to be repeated.

Conclusion

You who plan to build starships may be initiating a new phase in Galactic history. If we expand our presence beyond our Solar System through our probes, our role in the galaxy will begin to change.

We cannot foresee all the powers that our machines will have a century in our future, any more than people in 1913 could foresee what powers our machines have now.

We should think through the implications of succeeding ourselves with artificial Intelligence. What motivations should we instill in our intelligent machines? What limits on their behavior can we impose?

For those who would design artificially intelligent probes, I offer a warning. Be careful of what you loose upon the galaxy. Above all, do not give those machines the ability to reproduce themselves.

Someday, Humankind may praise or condemn what interstellar advocates and their successors actually do. Choose wisely.

Bookmarked this one too!

In the Next Generation episodes, Data has an evil twin….a monster….

If you believe in one, you’ll eventually believe in the other….

A very good post!

Who will listen?

So we should just stick to our own pale blue dot, because we may accidentally influence the environment (the universe) around us? nah… I’m getting back to work. AI won’t write itself!

The overall point of the article is interesting, but I must take issue with this statement:

“This model flies in the face of the only behavioral data base we humans have: our own history. No human expansion has continued unchecked. No technological program continues indefinitely.”

What exactly are you saying here? Humanity evolved and walked out of Africa perhaps millions or hundreds of thousands of years ago. I don’t see that we’ve slowed down as nearly every even marginally-inhabitable place on the Earth’s surface now has human civilization. With continued developments in private rockets it won’t be too long before there are people living in space as well. Given enough time – and we’ve only had the blink of an eye in cosmological terms – humanity shows no signs of slowing down expansion.

“What limits on their [intelligent machines’] behavior can we impose?”

1. A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2. A robot must obey the orders given to it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3. A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

4. A probe-robot must adhere strictly to the Prime Directive regarding non-interference in alien cultures, even if that adherence results in the violation of one or more of the First Three Laws.

I think it says a lot about people that many immediately assume an AI would be malevolent or dangerous. Humanity would be its mother. I think it would be much more likely to love us, or at least respect us. Dark and gloomy predictions sell newspapers and stock market newsletters and such.

I can’t think of any scenario that a space-based AI and humanity would compete for resources. We would more likely be partners or allies.

@David – Don’t forget the later zeroth law: “A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm”

I thought that Asimov’s books explicitly explored why these laws (which are hard/impossible to code?) were broken. Elijah Bailey and Susan Calvin never came up against malfunctioning AI probes, and worse, replicating ones.

If all advanced civilizations came to the same conclusion – no replicating probes – then one argument for the Fermi Paradox might collapse. We might be in a Clarke’s universe, extremely rare visits of a world over cosmic time. Conceivably long lived, non-replicating probes could be churned out in the trillions to restore the paradox.

I’m not sure I buy the strict non-interference argument. We would want a probe to explore a living world for scientific reasons. It would make sense for it to be a shape shifter to minimize its effect on the world. What criteria would be needed to be met for it to be allowed to contact with intelligent species?

Interesting article… ethics plays a pretty big role in determining whether and how we should interact with other lifeforms, particularly intelligent ones, as has been portrayed (sometimes crudely) in many episodes of Star Trek.

Ultimately, though, a totally “hands-off” approach is probably infeasible. Where humans have seen, humans (or their robots) have been, and where we (or our ‘bots) have been we have changed. Contact with aliens inevitably means both parties becoming aware of each other and “contamination” both ways- whether of the cultural or biological kind. Most likely, such direct contact will be the beginning of a new phase of history for both cultures.

What may be the best approach is to first observe another civilization from afar, and then deliberate carefully on how to proceed- make direct contact or declare the planet or star system off-limits?- assuming that we don’t accidentally reveal our existence to them first.

The nasty little SF story “We’re Civilized” by Mark Clifton and Alex Apostolides plays with this idea. The first rocket to Mars lands on a covered canal built by the inhabitants, who have a complex society based around their symbiotic relationship with the lichen their canals water. Because they see no signs of towns and air pollution the rocket crew do not recognize the Martians as being civilized, and the Martians don’t have any conception of rocket ships. They gather to roll away the big, hot meteor as the rocket becomes cool enough to touch, causing the rocket crew to panic and shoot all of them.

Once back on Earth, the rocket crew are hailed as heroes and presented with medals- but just as they step up to receive them, a bizarre alien spaceship materializes over the auditorium and inadvertently crushes most of the audience. Seeing no signs of civilization- their kind of civilization- the aliens get out and being claiming all that they survey while the cultural observer from the Mars rocket screams helplessly, “No!! We’re civilized!”

Perhaps it would be a good idea to ponder what “civilization” might actually be before we bring our assumptions to the rest of the universe!!

Agreed, this has been my issue with the Von Neumann probe idea and the Fermi Paradox- the assumption is that any interstellar exploration effort would exponentially expand from star to star without end, and leave a permanent presence at every star, indefinitely until the entire galaxy was explored.

But, as our own history shows, exploration as usually consisted of various fits and starts- not continuous programs- and no space project has continued indefinitely. If anything like the “continuous expansion” model happens, it would most likely be successive waves of exploration founding new colony planets, some if which send out new waves of colony ships later in their history. This could be a lot messier than the ideal Von Neumann model if not all expeditions succeed (they won’t) and planetary civilizations don’t last indefinitely (they might not, depending).

Great article. However:

Not unchecked, perhaps, but checked only by the boundaries of our planet that we (until now) could not physically transcend. KyleRice’s above arguments apply. Technological programs always end, but they are also always obsoleted by newer, more advanced programs.

We have long since gone way beyond the moon. We have not abandoned our space program. It has expanded from the moon to the outer reaches of our solar system in just half a century. Is that a sign of catharsis for you?

You are right, there is a theoretical possibility of such catharsis, but there is very little evidence for it in our own history. It may have existed for a limited time here or there, but it has always been overcome. Name one place that could be physically within our sphere of influence, but isn’t because we haven’t bothered to go there. Unclaimed territory, as it were.

Intelligent machines are inherently able to reproduce themselves, as long as they are smart enough to build machines. And for the universe, it makes no difference whatsoever if the machines that take it over have blobs of water and carbon controlling them, or intricately wired chips of silicon instead.

Contacting…even detecting another intelligent civilization within a 100 light years of our solar system seems like a long-shot?

Self-aware machines would inevitably have to act on what they understand.

‘You are here to explore. Discover within your framework of environment’

You could have just an autonomous system that maps all the objects in orbit around some alien Sun? You might even have it build a base. Maser communication node with a vacuum hangar and general service repair shop.

But what happens when your data collection shows ‘anomalies’ life ‘seasonal cycles of vegetation’ or ‘surface or areal migration’?

You might have that subset of ‘sealed instructions’ for a new mission that was 10 billion to 1 against! The contingency of extreme deep space exploration is the day we will find E.T.! I hoping we will have the advantage of knowing what ‘not to do’ as opposed to ‘we are over our heads with this.”

The real test of civilization is how we come to understand ‘the other’ and ‘their way of existence’…. how I envy our descendants.

Michael A. G. Michaud said; “Be careful of what you loose upon the galaxy. Above all, do not give those machines the ability to reproduce themselves.” Good advice, except that a colony itself can be regarded as a ‘self-reproducing machine’. Given time, a colony world could send out daughter colonies, and so on. The colonies could even mutate over time, into aggressive, ‘berserker’ colonies. Is that sufficient reason not to travel to the stars?

A fly through is not the most likely scenario for an interstellar probe. After expenditure of astronomical resources, you would want more payback than that, as Icarus is a stop-over in the target system, as opposed to Daedalus.

Christopher Phoenix:

Absolutely correct. Such an expansion will look “messy” and “fits and starts” on the time scale of decades, centuries, perhaps millenia. Looked upon at a larger scale, though, over millions of years, fluctuations would recede into insignificance and expansion would be continuous for all intents and purposes.

Steve Bowers:

Great point. Expansion of humanity has the exact same dangers for the universe as the uncontrolled expansion of AI. Unless, that is, if you postulate that humans have some sort of “Three Laws of Humanity” built into them that intelligent machines would lack. Call it ethics, if you will.

It comes down to these three questions: Do we trust our biological descendents more than the machines we build? Really? Why?

To quote Dr. Ian Malcolm from Jurassic Park:

“John, the kind of control you’re attempting simply is… it’s not possible. If there is one thing the history of evolution has taught us it’s that life will not be contained. Life breaks free, it expands to new territories and crashes through barriers, painfully, maybe even dangerously, but, uh… well, there it is.”

Our only guide for any of this is what happened here on Earth when humans expanded throughout the world, and when Europe began exploring/colonizing other cultures.

The overall effects of human expansion have not been benign: habitat loss, pollution, over-exploitation of natural resources. This was true even of some non-industrial societies, and industrialization has generally made it worse.

As far as exploration/colonization, a number of “alien” cultures withstood even aggressive contact and were eventually able to adapt European technology for their own purposes (Japan, China, India). Others (e.g. those of North America) were virtually annihilated, mostly unintentionally by introduced diseases that nobody could control.

It was luck of the draw that Europe itself was not annihilated by diseases introduced by returning explorers, or that it didn’t encounter an even more technologically-advanced culture that took exception to its activities.

Although we now have a better understanding of these issues than our ancestors did, it’s likely that factors we don’t know about will have a similar range of effects as we move out into the galaxy. We should be extremely cautious about doing so.

Interesting thought experiment that poses many questions with few answers. One point – HAL9000 did not so much override its programming as it was influenced by the monolith alien presence. HAL9000 did not evolve spontaneously beyond its intended programming.

Eniac: “Do we trust our biological descendents more than the machines we build?”

Great question. It isn’t so much what ethics we program into our machines (or in the case of self-replicating probes, if such programming can remain unchanged over many generations), but what ethics we embrace ourselves.

The consensus here on this forum is probably one of caution and careful non-interference, but who knows what the consensus will be among those who finally get around to building the first set of self-replicating probes.

Most of us here applaud the notion of private space exploration, but let’s think for a moment what that ultimately means. Already each of us has in our smart-phone more processing power than NASA had when it launched the Voyager probes, and that trend will continue indefinitely. Even if some hard size-limitation at the quantum level is reached, Moore’s Law will continue to describe the increase in the availability of cheap processing power.

And what happens if we achieve Nuclear Fusion as a viable power source, and electricity really does become “too cheap to meter” as predicted back 1954? I know, right now things don’t look great for fusion, but they don’t look great for interstellar travel either — right now — and yet here we all are discussing it, aren’t we?

From what I’ve read on the subject of nuclear fusion — despite its inability so far to achieve “ignition” — I think that it’s only a matter of time before it becomes not just a reality, but a change-the-world-forever reality.

At some point in the future the average human will have not only an amazing amount of personal CPU processing power but an amazing amount of cheap energy at his/her disposal. It might not be today, it might not be tomorrow but it will be sometime in the reasonable near future. 50 years? 100 years? What do such numbers mean against the timeline of “ever since the invention of agriculture”? Nothing, really. A mere blip of time.

And when that time comes, “private space exploration” is going to include the likelihood of “private self-replicating interstellar probe launches”.

Regulation of such activities can and will be attempted, I am sure. And such regulatory efforts will certainly fail.

The bottom line is, if we have nuclear fusion (and even if we don’t have it, but certainly if we do have it), private launches of Von Neumann probes will become practically an everyday occurrence.

I think another important point here is that self-replicating machines can be permanently programmed, if and only if they are not intelligent.

This follows from the rigorous properties of error checking and correction codes, and the assumption that by “intelligent” we mean smart enough to understand and alter their own programming. By “permanently programmed” I mean imprinted with rules that never change, except by deliberate, intelligent, tampering.

It is my opinion that self-replicating machines are around the corner, as a byproduct of rapid progress in automation, but real general intelligence may take a little longer. As I mentioned before, intelligent machines are necessarily capable of self-replication, but the reverse is not true.

Pondering the latter, I feel it might be more appropriate to say: “Be careful of what you loose upon the galaxy. Above all, do not give those machines the ability to think for themselves.”

For those who still argue that self-replicating machines would necessarily be subject to evolution, let me point out that evolution is a precarious balance between mutation rate, genetic redundancy, and environmental stability. If any of these are off, the result is either complete stagnation or extinction by error catastrophy.

Unless a (non-intelligent) self-replicating machine is deliberately designed to achieve this balance, it will be in the former category: Able to make replicates of itself with a perfect copy of the original genome, or fail to procreate at all.

Intelligent machines would, like ourselves, also not be subject to evolution in the traditional sense. Instead, they would deliberately improve their own design from generation to generation, and even for existing individuals. This is a historically unprecedented process the outcome of which we can not hope to predict. One thing is sure, though: The traditional mutation/selection approach is FAR too slow to matter anymore, at all.

Evolution has served its purpose. This is the dawn of the age of intelligent design!

I do not believe that a robot can ever duplicate man, because man has spirituality which cannot be defined but it is established by a Mozart, for example. The reason is that feelings or emotions cannot be put into a robot because they cannot be described by the laws of physics. At the most fundamental level these laws are quantum mechanics, which was discovered by Heisenberg making a lucky guess. But as Feynman has said nobody understands quantum mechanics, but for reasons unknown it always works. It leads to the mysterious entanglement, experimentally shown to act over 10km with a velocity 10 000 times faster than the speed of light. Without this entanglement of the quantum mechanical wavefunction in higher dimensional configuration space there would be no photosynthesis to make chlorophyll and no forms of life. It almost appears that the ancient idea of a spiritual soul is the most simple “explanation” for man to be different from a robot. Kant in his critique of the pure reason had shown that God, Freedom and Immortality can never be proven, but in his critique of the practical reason he calls them postulates, because without them there would be nihilism. If one day we will make contact with an alien civilization I would be mostly interested in thei culture: Do they have classical music like we have and do they have someone like a Mozart, Einstein and Heisenberg.

@Winterburg

By the same argument, we cannot feel either, because our bodies and neural systems are just based on chemistry and physics. While we cannot measure feelings directly, we can observe their neural correlates. Explaining them is a work in progress, but I have little doubt that it will eventually be solved. What you are arguing for is some sort of mind body dualism. This idea has long been rejected by scientists working in neuroscience.

Scholarly reference please. AFAIK, this is not true in terms of transmitting or receiving information. If it was, you can bet it would already be in operation at the stock exchanges by high frequency traders.

“The reason is that feelings or emotions cannot be put into a robot because they cannot be described by the laws of physics”

How would you describe emotions objectively. Think of someone becoming angrier and angrier. Note that in this thought experiment, the actions of that person become more and more stereotyped, and easier to predict as emotion increases. So… it would be easier for AI to imitate highly emotional humans, it’s the more rational mind where the true problem starts.

Rob: “So… it would be easier for AI to imitate highly emotional humans, it’s the more rational mind where the true problem starts.”

I agree. Have you heard of PARRY?

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PARRY

We could send neurotic AIs into the void and be comforted that they’d be less likely to change their objectives. One manifestation of many neuroses is that one cannot process information to change one’s worldview. This is perhaps a cruel but effective way to keep them at the assigned task.

Hmm…now I can’t decide if I’m joking or not.

There can be little doubt that through quantum mechanics we experience the existence of the “thing in itself ” (Kant: das Ding an sich ), without knowing what it is. Classical mechanics tells us what we must do to make a car, but quantum theory does not tell us what we must do to make a Mozart, which unlike a car works by the rules of quantum mechanics. Brian Greene in his “The Fabric of the Cosmos” page 123 correctly notes the observed quantum entanglement -Bell inequalty violating- EPR correlations “show us fundamentally, that space is not what we once thought it was”. This is consistent with Kant’s critique of the pure reason, where he notes that all our thinking is 3-dimensional euclidean. How can we make a robot in our ordinary space which should be built in a space we do not even know what it is? In a paper entitled “Teichmueller Space Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics” (see internet), which I had presented at the American Physical Society meeting in Denver this year, I had speculated that this space is a higher dimensional complex function Teichmueller space (see internet) below the Planck length, which could perhaps explain these strange correlations. If true, then we would have to built a robot in a Teichmueller space below the Planck length of 10^-33 cm. Who can do this?

“Duplicating man” is indeed the most difficult of the targets of AI. It is third in the series after specialized intelligence and general intelligence. It is closely related to mind-uploading, which could be seen as the fourth. General intelligence (number two) is sufficient for the dangers we are worried ahout here, no need to duplicate man.

Presumably you can be intelligent without being able to see, hear, enjoy a symphony, or even have much of any feelings at all. As evidence for the first two, we have blind and deaf people who are smart. For the third it would probably not be too hard to find examples, either. The fourth appears to be unexplored territory, although it might pay to look into psychiatric disorders characterized by lack of emotion.

I do not dare say whether artificial intelligence would be more or less dangerous with or without emotion. Perhaps if emotion could be added selectively: include love, but not hate, include joy, but not anger. That might work. Or, maybe not.

@ Friedwardt Winterberg

Based on what evidence?

There is doubt, lots of it, right here….

Interesting readings on the subject of Friendly AI by Eliezer Yudkowsky. The links range from conversational to highly technical:

http://intelligence.org/files/ComplexValues.pdf

http://intelligence.org/files/CFAI.pdf

http://wiki.lesswrong.com/wiki/Friendly_AI