Yesterday I wrote about what Michael Michaud calls ‘the new cosmic humanism,’ looking back at an essay the writer and diplomat wrote for Interdisciplinary Science Reviews in 1979. Intelligence, Michaud believes, creates the opportunity to reverse entropy at least on the local scale, and to impose choice on a universe whose purpose we do not otherwise understand. Continuing growth into space, expansion and discovery are the kind of long-term goals humans can share, highlighting the extension of knowledge and the rediversification of our species.

What Michaud is talking about is nothing less than a mission statement for extraterrestrial man, one that trades off a key uncertainty: In the face of an indifferent universe, intelligence itself may prove to be an evolutionary quirk that is of little consequence. Whether or not this is the case could depend on the decisions and purposeful choices of intelligent beings, assuming they choose to expand into the cosmos. Let me quote Michaud on this:

Intelligent beings evolved from planets can do that [i.e., influence the universe] only by adopting extraplanetary models of their futures, by committing themselves to purposes for the species that reach beyond individual lifetimes, and perhaps eventually by adopting goals that reach beyond the species itself. If evolution suggests any ultimate moral task, it is survival; intelligent beings with technology and social purpose are equipped with unique means to assure it.

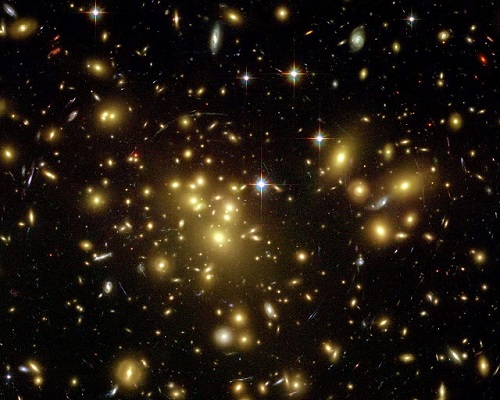

Image: The galaxy cluster Abell 1689, as seen from NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope. Faced with such immensity, what role do we assign intelligence in the ultimate fate of the universe? Credit: AFP/NASA.

The Price of Purpose

What Michaud calls cosmic humanism is not without its detractors, whose case emerges on practical grounds, and the author is wise to present it in the context of his larger argument. Anyone involved with the space community is challenged to explain why we should be looking beyond the Earth when we have so many problems here. Zero-sum arguments suggest that money spent on space is money taken away from social programs, leaving space advocates to argue the technological benefits that have accrued from the space program and future savings in areas like power generation.

These are arguments the space community has to be prepared to engage in with tangible benefits and a sensible eye toward budget realities. The moral argument can be trickier, and it also becomes ideological. Is space expansion just another way of imposing human chauvinism or preserving a Western model of industrial growth, a kind of futuristic ‘manifest destiny’? Is it in fact a thinly cloaked imperialism that turns the conflict of nation states into a model for future human conflict on other worlds, perhaps imposing our values on alien cultures?

We also run into the issue of limits. Michaud cites Philip Morrison, who has criticized the idea that there is any imperative for human expansion, arguing that as finite beings, we should be more attuned to our own limits. Added to this is the understandable argument that we have evolved in a biosphere for which we are now uniquely suited, and that expansion to other worlds would dilute and transform the species. Whether this is something to be deplored or celebrated is controversial, but certainly Michaud falls into line with Freeman Dyson as seeing diversification in society and ultimately biology as inevitable outcomes of an interstellar culture.

Behind all these objections lies the undeniable fact that a wide range of futures is within the realm of human choice, a philosophical stance varying from bounded to unbounded, a closed model vs. one open to expansion. Michaud points out that the window of opportunity for making a choice for the extraterrestrial paradigm is not necessarily infinite. We may run into serious issues of resource depletion within the next century that stymie our hopes for expansion.

Whether we take these outward steps depends on our motivations, on the values of our most powerful societies, and on political events within and between them. One might argue that, without an external goal, the world’s nations may have no purpose other than the periodic redistribution of wealth, status and power, often by force. By pointing out the promise of an extraterrestrial future, one might strengthen the case for solving current problems so that such a future can be realized.

Evolution of an Extraterrestrial Ethos

We cannot know what our species will ultimately choose, or whether natural or self-inflicted disaster will punctuate or even end future attempts at expansion into space. But what if our own extraterrestrial paradigm runs into the paradigm of another species? We may encounter, in the distant future, intelligent species that have chosen for their own reasons not to expand, perhaps through a lack of nearby destinations and resources or because of cultural values incompatible with colonizing other worlds. Or we may find expansionist beings whose interest is in shaping the universe to their own design to form a noosphere of interstellar dimension.

Here we can see Michaud the diplomat at work, asking how we might handle inevitable questions of contact and cooperation, subjects he would later address in Contact with Alien Civilizations: Our Hopes and Fears about Encountering Extraterrestrials (Copernicus, 2006). Would the need for survival of a single species lead to conflict between it and the newly discovered others, a Darwinian struggle that could produce permanent limits to growth? We will need to be thinking about such issues down the road if interstellar travel ever becomes a reality, for ultimately we will be called upon to make ethical decisions — the hard currency of intelligence — involving both survival and altruism.

For intelligence to survive, shared purpose will need to come to the fore in our dealings with other civilizations, with an emerging macro-intelligence being made up of the individual contributions of cultures in control of their local sphere of space. Such a ‘conscious universe’ gives itself purpose through its own survival and the effort to impose structure and meaning upon the cosmos. If intelligence is to have a long-term purpose, something like this may be it.

Lighting the Cosmos

And if we are alone in the universe? Just as I was thinking about these issues yesterday I ran across Vinton Cerf’s What If It’s Us?, a short essay on the Communications of the ACM website. Cerf will be known to Centauri Dreams readers and almost all digitally aware people as the father of the TCP/IP protocols that are at the heart of the Internet. He’s also fascinated with the human future in space, and when I read his new piece, I found a useful synergy with what Michael Michaud is saying in “The Extraterrestrial Paradigm.”

Cerf was at a conference held by the Internet Society to discuss the emerging protocols for interplanetary communication when guest speaker David Brin asked what we would do if there were no other civilizations out there. What if we are the ones who are supposed to light the galaxy? If our species is destined to bring intelligence into at least the local cosmos and, in Michaud’s terms, impose choice on inevitability, just think of the responsibility that places upon us. Do we have the capacity as a species to survive long enough to make it happen? Cerf’s thought echoes Michaud:

I cannot speak for anyone else, but I think I would think somewhat differently about a lot of things. I would be thinking more long-term and be worried about the sustainability of our planet and the species that inhabit it. I would wonder what we should be developing to fulfill this mission. What technologies do we need to expand beyond our planet and our solar system? How should we prepare ourselves for such an ultimate goal?

Either way, you see, we face the need for sustained vision and developing purpose, our choices governing the outcome either here on among the stars. We must be prepared, as Michaud explains, to impose that purpose on a cosmos in which intelligence is rare just as we are prepared for possible contact with other species whose ideas on these matters may differ. Culturally, developing an outward-looking paradigm is not the work of years or decades but of centuries, requiring sustained effort and continuing debate. Those who choose to ponder these things on the public stage are playing a valuable role in the evolution of human purpose. They are helping us create the interstellar mission statement that will guide our way forward.

“Intelligence, Michaud believes, creates the opportunity to reverse entropy at least on the local scale”.

I would think that all life does exactly that: reverse, or rather reduce entropy.

Bookmarked this excellent post:

It could be said that human sperm was designed to explore…

We are the enduring kin of that exploring sperm….

Michaud needn’t fret about the survival of the spirit of intelligence…

Arthur C. Clarke wrote a novel titled, “The City and the Stars”. In the novel he discusses a cosmic intelligence he named, ‘Vanamonde’, and its opposite, The Mad Mind’. It’s a pity Clarke hadn’t the passion to expand on these twin elements in another novel. But others have explored them in such places as the Holy Bible, and called them God and the Devil….

We are the enduring kin of the curious sperm….

Many will prefer their caves of security but they too are elements of every exploration…Wisely Clarke conceived of this reality as the city in his novel called Diaspar, the ultimate cave of security men will leave…JDS

“In the face of an indifferent universe, intelligence itself may prove to be an evolutionary quirk that is of little consequence.”

Nature cares little for intelligent. It’s just a series of mutations that has, so far, proved beneficial to humans. Should some massive disaster overtake us and reduce us to pre-civilization numbers again there is no reason to assume we would maintain our current level of intelligence.

Should the world following such a disaster be harsher, such as lower oxygen content in the atmosphere due to the die-off of the oceans from acidification, then evolution might move some of the resources devoted to bigger brains to better lung capacity. It would make sense. We would already know how to create things such as bow-and-arrows and optimally it could reduce our ability to innovate to better physically suit us to the new world. Instead we would only need to maintain enough intelligence to pass the knowledge of bow-and-arrows through the generations which would be considerably less than that needed to develop such instruments in the first place.

“Anyone involved with the space community is challenged to explain why we should be looking beyond the Earth when we have so many problems here. Zero-sum arguments suggest that money spent on space is money taken away from social programs, leaving space advocates to argue the technological benefits that have accrued from the space program and future savings in areas like power generation.”

Money taken from the space program would most likely go to the military which already has an excessive budget. I see little gain there for any country, or humanity as a whole, from doing that.

It’s not as though we’re throwing billions of dollars into space. A part of that money is spent to pay personnel who then buy goods with it. Some is spent on mining and buying the equipment needed to support the programs. In effect it drives the economy just as well as spending it on a new aircraft carrier would, or training more soldiers. It employes people who would otherwise be forced out of a job and would have to go on one of those social programs. The technological benefits that are derived from it are also considerable. Imagine just how of a benefit the GPS system has been, or more accurate weather forecasting. Those two alone has saved a considerable number of lives.

” Is it in fact a thinly cloaked imperialism that turns the conflict of nation states into a model for future human conflict on other worlds, perhaps imposing our values on alien cultures?”

There are no other intelligent species in our solar system, so how can we impose our values on them? (Unless they’re so far beyond us that we can’t even detect them, in which case the idea of imposing our values on them is laughable.)

By the time we reach other stars where there’s intelligent life I doubt the people traveling there would be culturally, and probably not even biologically, close to what we consider human today. The outcome of that isn’t something we can predict. Centuries on a ship were every resource must be conserved and recycled might root out every vestige of wastefulness creating a very different sort of society than the ones we’re used to.

But then I’m all for space exploration, and colonization, even to the point where I believe we should seriously consider project Orion (the one where we use nuclear bombs) to start moving large amounts of infrastructure into space. I mean, how is it sane to build tens of thousands of nuclear weapons that could have destroyed our civilization by accident, yet totally rule out such a cheap and powerful access to space that could be a game changer for our species? It makes no sense to me.

Articulating or forming a very long term vision of Earth-originating life’s potential, and binding that vision to our survival instincts as well as our aesthetic or intellectual instincts, seems like a daunting task. But I’ve been running across this idea in more and more places.

In a geopolitical phase as fractured as ours, can such a symbol be envisioned? What long-term project would be vivid or inclusive enough? As you suggest, if it’s an effort towards interstellar travel, it’d do well to solve some puzzles here on Earth along the way. This is quite reasonable and far from unreachable (doing both).

Perhaps the symbolic effort that would ignite such a long term striving would focus on close stepping stones, but point inevitably beyond them. In its own way, life itself always points beyond itself. All limits suggest something beyond them.

These last two posts are very good! I have long been of the opinion that there is a need for an explicit ideological and even spiritual movement to guide and drive space exploration. Right now the space movement seems fragmented, directionless, and culturally rather marginal.

I have recently completed a Master’s Thesis which seeks to address these problems. It offers a broad outline of a “Cosmist” ideological space movement. If anyone is interested, it is available here: http://thecosmist.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Cosmism-An-Ideological-Outline-of-a-New-Space-Movement.pdf

Here are the concluding paragraphs, to give you the flavor:

This paper has offered a broad overview of a worldview called Cosmism. We have attempted to justify and motivate the Cosmist idea, discussed its history and proposed it as an ideological foundation for our civilization going forward. We have described an emerging Cosmist spirituality that could form the basis of a new cosmic religiosity that Einstein and other visionaries have predicted, and offered some ideas for the creation of a formal Cosmist organization.

There is a rich literature and culture surrounding the Cosmist idea that seems worthy of greater influence and attention in our time. Does it not seem strange that our civilization, so materially enriched by science and technology, seems so lacking in a scientifically-informed higher vision for itself and its future? Hopefully this paper has given the reader a better appreciation for the many great ideas of Cosmist thinkers who have offered such higher visions until now. Cosmists are people who have heard the call of space powerfully, while most seem not to be listening at all. This paper has been one more Cosmist’s attempt at a wake-up call.

It seems fitting to conclude by quoting the man who most inspired this paper – the late, great poet of the Cosmist idea, Carl Sagan:

“The Cosmos extends, for all practical purposes, forever. After a brief sedentary hiatus, we are resuming our ancient nomadic way of life. Our remote descendants, safely arrayed on many worlds through the Solar System and beyond, will be unified by their common heritage, by their regard for their home planet, and by the knowledge that, whatever other life may be, the only humans in all the Universe come from Earth.

They will gaze up and strain to find the pale blue dot in their skies. They will love it no less for its obscurity and fragility. They will marvel at how vulnerable the repository of all our potential once was, how perilous our infancy, how humble our beginnings, how many rivers we had to cross before we found our way.”

Life increases entropy as the conversion of energy to locally reverse entropy is imperfect. We’re just a little low entropy bubble that increases cosmic entropy to sustain it.

@Sean. Interesting reading. To offer a complete opposite, a friend of mind saw humanity as nothing less than a disease and opposed any extra terrestrial spread. Neither of us was ever able to change the opinion of the other in this regard.

My friend’s view isn’t that dissimilar to that of the green movement. When Stewart Brand covered O’Neill’s ideas in CoEvolution Quarterly, the response was both positive and negative. IIRC, Wendell Berry was particularly dismissive of the space colony idea.

@ Heath Rezabek – The cosmist meme might be usefully embedded in your Vessels.

Two aspects of discovery I find highly captivating and able to overcome inertial relate more to technological innovation and breakthrough. These are ‘believability’ and ‘elegance of design.’ For example, quality science fiction has the element of believability – a foundation that can be accepted without too much difficulty and has an appeal of familiarity or nearness – makes a narrative more engaging. Believability (believe it or not) was a central principle of the original Star Trek production. Elegance of design we see in the form of sailing craft, aircraft, etc., but is often missing in our visualisations of space technology where our intellect, dealing with abstracts such as the ‘vacuum of space’ has offered transport in the form of cylinders and orbs in various combinations where the elegance of design is not apparently manifest. For example, at first glance the concept of a Start Wisp magnetic sail conjures up exotic visions of a space clipper with gossamer sails of magnetic flux, however the working models viewable online, with their centrifugal wire brush design, fail to generate the pleasing effect of elegant design that was so powerful in movies such as 2001 A Space Odyssey.

Believability and design elegance are mutually re-enforcing. The elegance of a design makes it more convincing and helps overcome the barrier to belief.

I think that the aspects of believability and design and the fascination they generate could help overcome some of the inertia we feel dragging us back to earth.

@ProjectStudio – I think “believability”, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Aesthetics differ depending on whether you are a fashion designer, an engineer, a mathematician or a scientist. Long experience with terrestrial life and artifacts have informed our perceptions of elegance in design, although these may be subject to fashion, like architecture.

When 2001: A Space Odyssey (the movie) appeared, the aesthetic of spacecraft design was changed irrevocably. I personally did not find the designs in any way jarring. Since then, we have been subjected to ever more extremes in this design for space aesthetic.

I personally find the designs for electric or microwave beamed sails very elegant because they represent almost extreme forms of minimalist design, an aesthetic which has had an impact at least since Buckminster Fuller with his “less is more” doctrine. Geodesic domes and tent structures in architecture follow this ethos, so why not spacecraft that should minimize mass to improve performance?

Alex, I should clarify – yes I did mean that aesthetics are a component of an elegant design. Elegance is a way aesthetics can be married to a reconciliation of a contending technical requirements in an ingenious way. An example, with jet aircraft, is the *way* designers incorporated a narrowing of the fuselage and adjustable swept wing design to meet the requirements of supersonic flight.

I don’t know what designers may arrive at to reconcile the requirements of interstellar travel. Minimalism may be a driving aesthetic. But I feel that the elegance of proposed solutions will help the cause.

“Anyone involved with the space community is challenged to explain why we should be looking beyond the Earth when we have so many problems here. Zero-sum arguments suggest that money spent on space is money taken away from social programs” — Paul, I do hope that whenever you hear this tired old cliché you promptly and firmly correct it! Obviously, the whole point is that civilisation is not a zero-sum game at all, but an increasing sum game.

We are not in the least “challenged” to explain why we are looking beyond Earth, because the choice is not between spending time and money on spaceflight or spending it on developing Earth. It is between maintaining a dynamic civilisation or a static one. A dynamic civilisation embraces change, believing (usually correctly) that change improves the lives of the broad mass of people. A static one attempts to stifle change, believing (usually correctly) that change is detrimental to the power of the ruling elite.

A dynamic civilisation will therefore develop and grow, in terms both of its geographical or astronomical reach and of its institutions of political responsiveness and social justice (as well as in many other areas: technological capabilities, population size, energy consumption, individual rights and liberties, intellectual freedom). A static civilisation will do neither. By developing spaceflight, we ARE also developing Earth itself: the one cannot fail to impact the other.

I believe that this point can be illustrated with numerous examples from history, starting obviously with our current model of democratic liberal market capitalist expansionist Enlightenment civilisation, as compared with the prior civilisations of Europe, the Middle East, Asia and the Americas.

Stephen A.

@Astronist: Here is a pessimistic view that I have not yet bought into because I desperately do not want my 13 and 10 year old children to face it.

This “democratic liberal market capitalist expansionist Enlightenment civilisation” is a model of civilisation in Earth history that is fast approaching its denouement. Its successor is shaping up to be oligarchic, corporatist, mercenary, and unenlightened.

It will be populated with billions of unemployed humans left aimless due to robotics and computers assuming the jobs that persons once performed. The corporate oligarchs will rely on a a 21st century version of bread and circuses, using virtual reality and synthetic food production to keep the majority of the populace from revolting.

How will this future be sidestepped in a way that allows my grandchildren to populate Mars, and my great-grandchildren to reach the outer Solar System?

@Astronist

This is really the same argument as the economic investment preferences. Do we spemd resources investing directly in improving Earth, or do we use resources for Extra-terrestrial investment? The Space development argument is that this has greater payoffs. Whether this is true of not is unknown at this point. History, as you say, suggests that the payoff can be very large, in the long term.

However, we can also look at this as a consumption vs investment question. This was the way it was usually framed post-Apollo. “Consumption” being current investment in immediate, short-term, economic growth, whilst investment was long term payoff. The optimal preference moving between the extremes depending on viewpoint. For long term payoffs, the investment really looks like consumption (all costs, no returns over the medium term horizon). Therefore it can be argued that space development, especially if significant, depresses economic growth for the majority of the citizenry, benefiting few. An historical analogy might be pyramid building. Similarly, are we sure we are not involved in malinvestment, e.g. trying to build the equivalent of ornithopters or a steampunk space civilization?

Therefore, I do not think it is so easy to dismiss the objections to [human] space development. Can we unequivocally state that manned spaceflight spending by Nasa for the last 50 years has benefited all Americans compared to spending the same resources in some alternative investments? Can we say the same for future manned spaceflight investments?

@ProjectStudio – I think we need to be very careful about what we mean by elegance and aesthetics. They are not orthogonal attributes. Neither are they fixed, as canonical examples may be very difference in different periods, e.g. architectural styles.

@Eric Landahl: an interesting point, but many would disagree with it, e.g. here:

http://www.technologyreview.com/view/519016/stop-saying-robots-are-destroying-jobs-they-arent/

I think to some extent you answer your own question by talking about populating Mars and the rest of the Solar System. These tasks will create new employment opportunities for well-educated people, they will benefit hugely from automation, yet cannot themselves be automated.

@Alex Tolley: you misunderstand me. I’m not saying that resources will be spent either on improving Earth or on space exploration, but (a trivial point, really) that they will be spent on both, and the most creative type of society is one which finds the right balance between both.

Clearly manned spaceflight spending has so far not benefited us as much as it might have done, because the market growth and consequent job growth that should have flowed from it have been held back by space agencies wedded to the view that the only humans who ought to be in space should be government operatives. Forthcoming developments from SpaceX and Bigelow and their competitors will hopefully get us past this hurdle.

Pyramid building was clearly a major employer while it lasted. The problem was that ancient societies did not find a way to develop the industry further. In space, by contrast, the potential for development will remain quite large for some centuries to come.

Stephen A.

@Astronist – I don’t believe I misunderstood you at all. You also seem to be agreeing that long term benefits of human spaceflight have not proven very good investments to date. Arguing that they would be if some alternative reality existed is rather disingenuous.

The whole point of investment analysis is to maximize the current value of the investment mix, discounting future returns for risk and timing. It is quite possible that immediate investment in terrestrial projects will result in greater wealth because the immediate growth supports the deferred long term space colonization effort, rather than being underinvested to support human spaceflight today.

Of course this is all speculative as we cannot know the future. H0wever one should be skeptical of claims of huge future returns and benefits based on little more than faith, wishes and appeals to flawed historical analogies. If there is to be large investments made in this endeavor, better it is private risk capital rather than public.

@Alex Tolley: “You also seem to be agreeing that long term benefits of human spaceflight have not proven very good investments to date.” — I do not. Although the effort so far has not been as efficient as it might, it has nevertheless brought technology to the stage where private companies are on the verge of taking over the Earth to orbit transport system, which in my view is immensely important, and without which Michael Michaud’s mission statement in the post above will not be effective.

“H0wever one should be skeptical of claims of huge future returns and benefits based on little more than faith, wishes and appeals to flawed historical analogies.” — Agreed, of course.

Stephen A.

@Atronist. This book review about the transcontinental railroads offers an interesting, modern parallel, to the US manned space program (ignore the libertarian, Austrian economics plug at the end). Substitute aerospace/defense contractors for the shady entrepreneurs like Durant, the justifications are very similar. Today the railroads carry a fraction of the people and goods across the US compared to trucks, cars and planes.

Did the transcontinental railroads “open up” mass transit across the continent, that evolved into the forms we have today? Or were they a temporary transport approach that had little impact on the future? Would the US government have done better investing elsewhere? Is the government funded manned space program paving the way for a private program that is more like the birth of air transport, where mail carrying was the model to jump start the business that evolved into the huge, international, airline businesses of today?

Hi Paul,

As a journalist (by training) I must tell you that the quality of your articles is fantastic. Your archives section is a treasure.

George

(Australia)