Nick Nielsen today tackles an issue we’ve often discussed in these pages, the space-based infrastructure many of us assume necessary for deep space exploration. But infrastructures grow in complexity in relation to the demands placed upon them, and a starship would, as Nick notes, be the most complex machine ever constructed by human hands. Are there infrastructure options, including building such vehicles on Earth, and what sort of societies would the choice among them eventually produce? You’ll find more of Nielsen’s writing in his blogs Grand Strategy: The View from Oregon and Grand Strategy Annex. In addition to his continuing work for the space community, Nick is a contributing analyst with strategic consulting firm Wikistrat.

by J. N. Nielsen

Although we have spacecraft in orbit around Earth, as well as on the moon and other planets and their moons, and even spacecraft now in interstellar space, so that the products of human industry are to be found throughout our solar system and beyond, we have as yet no industrial infrastructure off the surface of the Earth, and this is important. I will try to explain how and why this is important, and why it will remain important, potentially shaping the structure of our civilization.

Made on Earth

All our spacecraft to date have been built on Earth where we possess an industrial infrastructure that makes this possible. The International Space Station, of course, was assembled in orbit from components built on the surface of the Earth and boosted into space on rockets. It has long been assumed, if we were to build a very large spacecraft (say, for a journey to Mars or beyond), that it would be constructed in much the same way: the components would be engineered on Earth and assembled in space. There is an obvious terrestrial analogy for this: we build our ships on land, where it is convenient to do the work, and then launch them only when the hull is seaworthy. Once the hull is in the water it is fitted out, and then come sea trials, but it would not be worth the trouble to try to build the hull of a ship in the water.

The analogy, however, seems misleading when applied to space. In space, we could build very large spacecraft in microgravity environments that would considerably ease the task of manipulating awkwardly large and heavy components. Also, large spacecraft never intended to enter into planetary atmospheres could be built in the vacuum of space with no concern for the aerodynamics that are crucial for a craft operating in a planetary atmosphere. The stresses of transiting a planetary atmosphere would be an unnecessary requirement for most deep-space vehicles. But what would it take to really build a spacecraft in space, in contradistinction to the assembly of completed modules in orbit?

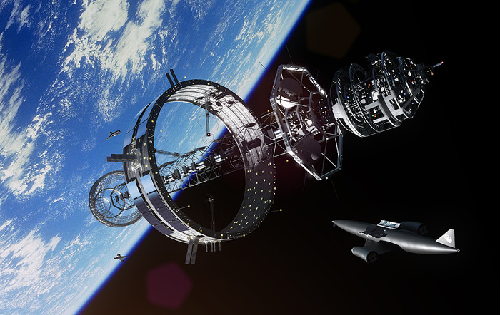

Image: One take on building starships in space. This view of the Project Icarus orbital construction ring prototype design shows resupply from the Skylon single stage to orbit spacecraft now under development by Reaction Engines. Credit: Adrian Mann.

Even a “basic machine shop” in orbit would not come close to providing the kind of industrial infrastructure we have been building on the surface of the Earth for more than two hundred years now. Production processes ripple outward until they involve much of the planet’s industrial production capacity, a lesson that can be illustrated by Adam Smith’s famous example of the day-laborer’s woolen coat or by what Austrian economist Eugen Böhm von Bawerk called round-about production processes. [2] I suspect that many will argue that the advent of 3D printing is going to change everything, and that all you need to do is to boost a 3D printer into orbit and then you can produce anything that you might need in orbit. Well, not quite.

The Growth of Infrastructure

As civilization grows more complex, infrastructure becomes more complex, and more precursors are necessary to achieving the basic functionality assumed by the institutions of society. We see this in the increasing complexity of our cities. There was a time when cutting edge technology meant bringing water into a city with aqueducts and having underground sewers to carry away the waste. To the infrastructure of water supplies we have added fossil fuel supplies, electricity supplies, telecommunications lines, and now fiber optic cables for high speed internet access. (On the growing infrastructure of civilization cf. my post The Computational Infrastructure of Civilization.) All of these infrastructure requirements have been continually updated since their initial installation, so that, for example, the electricity grid is significantly more advanced today than when introduced.

For the lifeway of nomadic foragers, no infrastructure is necessary except for a knowledge of edible plants and available game. Since the geographical expansion of nomadic foragers is slow, change in requisite knowledge is also slow, as a moving band of foragers only very gradually sees the diminution of traditional dietary staples and only very gradually sees the emergence of unfamiliar plants and animals. Much greater infrastructure characterizes agrarian-ecclesiastical civilization, and much greater still industrial-technological civilization. The extraterrestrialization of industrial-technological civilization (yielding extraterrestrial-technological civilization) requires an order of magnitude of increase in infrastructure for the necessary maintenance of human life.

How to Build a Starship

The spacecraft requisite to the achievement of extraterrestrialization are today, and are likely to remain, the most complex and sophisticated machines ever built by human beings. To produce not only their components, but the machines required to produce the components, requires the entire advanced infrastructure that we now possess in our most developed centers of manufacturing. A useful analogy for understanding the industrial requirements for the production of spacecraft is to think of building the spacecraft of the future as we think today of building a nuclear-powered submarine. Like a nuclear submarine, an SSTO (single stage to orbit) spacecraft will be one of the most technically difficult and demanding engineering tasks ever attempted; it will involve parts suppliers from all over the world; it will involve millions of individual parts that each have to fitted in place by a human hand, and the assembly itself is likely to require many years of painstaking construction.

There is another sense in which spacecraft probably will be like nuclear submarines: a spacecraft is going to have significant power demands, and the most compact way to address this with our current technology is what we now do with your biggest submarines: nuclear power. The compact reactors on submarines (and aircraft carriers, which typically have two reactors for redundancy) have proved themselves to be safe and serviceable, and they can keep generating power for 25-30 years without refueling – possibly a sufficient period of time to make an interstellar journey. We can, of course, readily make use of solar power in space, though this is not compact and would not be suitable for a starship, which would be operating for extended periods of time far from the light of the sun or any other star.

I think it is clear that once we attain the ability to produce technologies commensurate to the challenge of a practicable starship, we are likely going to want to employ more than one propulsion technology, so that the drive system is highly hybridized. By “hybridized” I mean two or more forms of propulsion on a single spacecraft, and if these multiple forms of propulsion can share structures of the propulsion system, the more they do so the more truly “hybrid” the propulsion design. We may want to have one drive system for use in planetary atmospheres, another for orbital maneuvering, a third for interplanetary travel, and lastly a drive for interstellar travel. Later that list may need to be lengthened for a drive for intergalactic travel.

Hybrid propulsion systems are already in development, and these innovations could greatly improve the efficiency of chemical rockets. I have written many times about the Skylon spaceplane with its “combined cycle” SABRE engines that operate as conventional jet engines in the atmosphere, and which are able to transition to rocket propulsion for exoatmospheric operation. (Cf., e.g., Skylon spaceplane engine concept achieves key milestone, Key Tests for Skylon Spaceplane Project, Move to Open Sky for Skylon Spaceplace, and Addendum on Jet Propulsion Technology) This is a truly hybrid propulsion system, as the jet engine and chemical rocket share structures of the propulsion system, though it remains within the parameters of chemical rockets.

For faster travel to farther destinations, we will need hybrid propulsion systems of exotic technologies that do not exist today except in theory. A spacecraft with an Alcubierre drive and some basic form of chemical or nuclear or ion thrusters might be able to do the job, and this might well be the first step in building a starship that give us access to the galaxy in the way that we now have access to the surface of Earth. However, a spacecraft with an Alcubierre drive and a fusion or antimatter drive, or with Q-thrusters, would be much better. If, for example, you traveled to our closest cosmic neighbor, Alpha Centauri, you might want to travel the greater part of the distance with the Alcubierre drive, but once you get there you would probably want to make your passage between Proxima Centauri, Alpha Centauri A, and Alpha Centauri B with your fusion or antimatter drive, and you would definitely want to explore the planets of these stars with this “slower” drive. (And you probably wouldn’t want to use something like a Bussard ramjet for transit within a solar system.)

Two Responses to the Infrastructure Problem

A spacecraft mounting the kind of hybridized propulsion systems outlined above would represent an order of magnitude complexity even beyond the example of assembling a nuclear submarine. For the next few decades at least, and perhaps for longer, there will be no machine tools and no industrial plant in space. All the facilities we need to build a large and complex engineering project that is likely to occupy many years of painstaking effort, are earth-bound. Moreover, such technical assembly work would probably need to be performed by skilled craftsmen in a familiar environment conducive to careful and patient work. While there are significant advantages to constructing spacecraft in orbit, as noted above, the world’s most advanced industrial plant and best construction teams are on the earth and will be for some time, so that there remain compelling reasons for continuing to construct spacecraft on Earth, despite being at the bottom of a gravity well. This, in a nutshell, is the infrastructure problem.

There are two obvious responses to the infrastructure problem: (1) we accept the limitations of our industrial plant at face value and organize all space construction efforts around the assumption that spacecraft will be built on Earth, or (2) we begin the long task of constructing an industrial infrastructure off the surface of Earth. This latter approach may take as long as or longer than the building of our industrial infrastructure on Earth. While we have the advantage of higher technology and knowing what it is we want to produce, we also face the disadvantage of the harsh environment of space, and the need to initially boost from the surface of Earth everything not only required for industry, but also everything required for human life.

Almost certainly any human future in space will consist of some compromise between these two approaches, with the compromise tending either toward Earth-based industry or space-based industry. The model of extraterrestrialization that eventually prevails will not only be a matter of socioeconomic choice, but also a function of what is technological possible and what is technologically practicable. This latter requirement is insufficiently appreciated.

The Role of Contingency

The large-scale structure of human civilization, once it expands into space (provided we do not languish in permanent stagnation) will depend upon technological innovations that have not yet happened, and therefore the parameters of which are not yet known. That is to say, humanity as a spacefaring civilization is not indifferent to how we are able to travel in space, and how we are able to travel in space will be a result of the sciences we develop, the technologies that emerge from this science, and which among these technologies prove to be something that can be engineered into a practical vehicle, in terms of extraterrestrial transportation.

Just as we as a species are subject to contingencies related to the climatological conditions that shaped our evolution, the geography that has shaped our civilization, the gravity well of the Earth as a function of its mass that constrained our initial entry into space, and eventually the layout of our solar system as it will shape the initial spacefaring civilization that we can build in the vicinity of our own star, so too we are subject to contingencies that will arise out of our own actions (and inactions). These latter contingencies include the sciences we pursue, the technologies we develop, and the engineering of which we are capable. The human contingencies that determine the structure of our civilization in the future also include unknowns such as exactly which science, technology, and engineering projects get funding (cf. my recent post Why the Future Doesn’t Get Funded).

If it turns out that the science behind the Alcubierre drive concept is sound, and that this science can be the basis of a technology, and this technology can be engineered into a practicable starship, we may never construct an industrial infrastructure in space. It may prove to be easier to construct starships not as massive works slowly assembled in Earth orbit, but rather as relatively compact spacecraft constructed in the convenience of a hangar, which, once finished, can be rolled out onto the tarmac, fired up, and blasted into space, thence to activate its Alcubierre drive once in orbit in order to fly off to other worlds. If, in addition, habitable planets (or planets that can be made habitable) are not too rare in the Milky Way, and human beings prefer to spend their time planetside, the industrialization of space may never occur. In this scenario, space-based industry always remains marginal, even as we become a spacefaring civilization.

As it is, we already today seeing the beginnings of the gradual transition of our industrial infrastructure into something cleaner than the smoke-belching chimneys of the early industrial revolution. As this process continues, and we continue to improve the efficiency of solar cells, there may be little or no economic benefit for moving industry into space. We may pass a threshold, beyond which Earth-based industry can be made entirely benign, therefore obviating the need to move industry into space. But all of this hinges on unknowns of an eminently practical sort, and which we cannot predict until we have actual experience operating the technologies in question.

Space-Based Infrastructure and Planetary-Based Infrastructure

If the Alcubierre drive turns out to be impracticable, or even not practicable at technological levels of development obtainable in the next few hundred years, then the need to construct different kinds of spacecraft will be more pressing. The idea of building a sleek spacecraft in a hangar and blasting off to other worlds directly from Earth’s surface may be impossible. In this case, becoming a spacefaring species, and especially becoming a starfaring species, will likely mean the construction of enormous industrial works off the surface of the Earth, initially assembling large spacecraft in Earth orbit or beyond, but gradually providing more and more goods and services in space without having to boost them all from the ground, which means the industrialization of space.

The industrialization of space, in turn, would mean a very different kind of large-scale spacefaring civilization than a spacefaring civilization that had no need of the industrialization of space, as described in the examples above. A spacefaring civilization of primarily space-based industry would be distinct from a spacefaring civilization of primarily planetary-based industry. Distinct social, political, and economic institutions and imperatives would emerge from these distinct industrial infrastructures.

If, as Marx claimed, ideological superstructures follow from the economic infrastructure that the former emerge to justify, [3] then it is to be expected that space-based economic infrastructure will produce an ideological superstructure distinct from planetary-based economic infrastructure. In the distant future, when we have occasion to survey many different spacefaring civilizations, this may prove to be a fundamental distinction that divides them.

Notes

[1] At the Icarus Interstellar Starship Congress last year, a member of the audience asked a question of Kelvin Long in which the questioner used the phrase, “the infrastructure problem,” which strikes me as the perfect formulation for the topics I am covering today.

[2] On Adam Smith’s example of the day-laborer’s woolen coat cf. Smith’s The Wealth of Nations, the final paragraph of Book I, chapter 1; on round-about production processes in the work of Eugen Böhm von Bawerk, cf. Thesis 22 of my book Political Economy of Globalization.

[3] The locus classicus for this Marxian view is to be found in Marx’s A Contribution to The Critique of Political Economy, translated from the Second German Edition by N. I. Stone, Chicago: Charles H. Kerr & Company, 1911, Author’s Preface, pp. 11-12: “In the social production which men carry on they enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will, these relations of production correspond to a definite stage of development of their material powers of production. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society — the real foundation, on which rise legal and political superstructures and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production in material life determines the general character of social, political, and spiritual processes of life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary, their social existence determines their consciousness.” Note that Marx usually refers to the “economic base” of a society rather than to its “economic infrastructure.”

Perhaps first we should figure out how to circumvent Russian politics when it comes to getting American astronauts back into space:

http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/04/29/ukraine-crisis-usa-technology-idUSL6N0NL2XE20140429

To quote:

“A deputy prime minister suggested that U.S. astronauts, who depend on Russian rockets to get to the International Space Station (ISS), use trampolines to reach it instead.”

Again, this is the kind of crap that will keep us from permanently staying in space.

Well , as Michael said pure iron does exist in the lunar topsoil , so perhabs Ilmenite should not be our first mining project . Pure Iron has so far been found only in concentracions of 0.5%, but is seems reasonable that this could be enriched to several % befor grinding the soil to a level that makes complete separation possible .

The first job for our small teleoperated robots , would then be to drive around with a specialized atachment which turns over the soil ( like a plow or discus) , while catching the pure iron contaning particles magneticly . Lets say this would give us a 20% iron material .

When a few tons has been collected , our little friends will change tools and asemble and operate the grinding & final separation setup.

Eventually we have perhabs one ton of pure iron powder , wich can be processed using powder metalurgy . In this way the compleks componenents for whatever can be created at a much lower temperature than smelting operations . Perhaps we would want to build a Brayton cycle solar generator , or maybe just a few 1oo kg size transport vehicles for which we brougt the motors and batteries form earth .

The extent of our space construction expertise to date is bolting together ISS modules. There’s a long way to go. The moon is a great place to start. But the ISS astronauts could start doing something in the immediate environs of the ISS too. Baby steps at least, rather than nothing at all.

“Alex Tolley April 29, 2014 at 10:21

@ljk

1. Contact your representatives in government and make your voice heard. If they get more than a few letters on this subject even they will pay attention.

2. Educate the public on space. Show them that space exploration and utilization is more than just science fiction. Do not let Tyson and Cosmos do all the work. And for the love of Pete, show them how interesting and exciting the real Universe is! And directly connected and beneficial to their lives.

How soon we forget. Nasa had all the money it wanted in the 1960?s, with an “exciting” Moon landing and exploration program, and….the public lost interest. By Apollo 13 the public was complaining about tv schedule pre-emption.”

@Alex Tolley

“The result is still a largely indifferent/incurious public. My own 2 offspring never even looked at my extensive library of books, both fact and fiction, so none of my enthusiasm rubbed off. I find the current crop of science students at a UC campus where I teach remarkably incurious about their major subjects, let alone space.

I suspect the problem is a some sort of malaise. ”

yes there IS malaise. what can be done ??

These teleoperated robots seem like putting the cart before the horse. My ideas are simpler and literally closer to home things the public can do to support space exploration.

So people weren’t interested in the Apollo lunar missions. How much of this is actually true? Did someone do a real survey and not just rely on a quote from Apollo 13? Oh I know there are plenty of people who do not care about space or understand the science behind it all, but I think the actions of one Richard M. Nixon did a lot more to derail America’s future in space.

So before we spend another twenty comments discussing these remotely controlled space robots, what are people here going to do to NOW to get the public interested in space in the first place so we can make a permanent presence there? I have already made my suggestions.

I don’t care if the public doesn’t get space or is terribly interested. The future of human civilization depends on our expansion into space. Literally.

So stop using that as an excuse and roadblock and let us start fixing the problem before it is too late.

@ljk

I could rephrase this to connote another context:

I don’t care if those people have not heard out our God or wants to follow theirs. The future of human civilization depends on all people getting to the afterlife we have been promised. Go forth and spread the word (or kill the unbelievers if they won’t convert)

Not subtle, but you get the point.

While Nixon did end the Apollo era spending, bear in mind that Kennedy wasn’t exactly pure in this regard either. He wanted a way to show US superiority to the Russians during the Cold War. From what I have read, he didn’t really want to do anything quite so grand as Apollo. Not to defend him, but by the time Nixon cut back the space program, the US economy was in real difficulties supporting a protracted War in Vietnam.

I think the point others make is that the public has to be involved, not just cheer leading. If space is just for scientific elites and a few government trained astronauts, it won’t involve them. If everyone had potential access to space, that might well make it popular. Appeal to people’s baser instincts – make space a visceral emotion – like taking a roller coaster ride (suborbital flight). Space has to become a destination that appeals to everyman.

Take my phrase as you will, but if you or anyone thinks we can keep maintaining on this one planet the level of population growth, industrial mining and drilling, and construction that our current civilization has been doing for a while now without consequences down the road, then I think you will find that physics and nature will be far harsher punishers than anything I have said.

There was a time when space was treated as the New Frontier just as the New World once was. We need to invoke that again. However, the shadows of the reaction to Newt Gingrich’s suggestion of a lunar base by 2020 during the 2012 US Presidential election still make me wonder how much pioneering spirit is left these days. Most people seem to have exchanged it for perceived comfort and safety and we know what else that will bring.

And I will say it again and again, we either expand into space as a species or wait to die – or worse, become a bunch of sheep living in a perpetual Middle Ages.

Oh yes, about equating my declaration to a religious dogma: Religion has done pretty good staying in business selling a destination that cannot be seen and likely does not even exist. Space has the advantage of actually being real, tangible, and a place humans can reach.

I was also trying to say that just because people remain ignorant does not mean the problems or the solutions should therefore go away.

We need a road map, we need to look at each step of the problems on that road map and solve them in parallel with as many minds as possible. Indifference to space is a problem and therefore there must be solutions to it. If we had travelling road shows to schools we could tell them about it, but we need to tell them what we need to do and that we need their help, engage with them.

Look what these youngsters did!

http://settlement.arc.nasa.gov/Contest/Results/2014/GREENSPACE.pdf

http://settlement.arc.nasa.gov/Contest/Results/2014/VONA.pdf

I personally find it humbling, there are young people out there who care, we need to get hold of them and keep them in the fold.

If a group of peers could look at their work and improve on it we could keep them engaged, they are the next generation.

A lot depends on the size of the construction blocks, or modules. If a large spaceship can be assembled from a series of smaller blocks that can be lifted into space, then these smaller blocks can be almost entirely built and fitted on Earth, and only connections will be required in space. If such a breakdown is not possible, then we will need large assembly facilities in orbit. If the materials come from the Earth, I don’t really see the point in shipping raw materials up into space to be manufactured. We should send finished products that just need to be assembled. There are some manufacturing processes that might benefit from space though. Foundry and casting work in particular might profit from the absence of contaminants. A typical example being heat pipes, that are, in some cases, filled with lithium and similar metals that are very sensitive to nitrogen and oxygen contamination, even in tiny fractions.

A test station for space drives would also be a great space installation. One of the major stumbling blocks in ion drive and fusion drive testing is that it is not practical to build vacuum chambers that can be pumped out as fast as the drives fill them with reaction products. A large solar array (ideally very large!), with adequate power conditioning and a small lab would provide a great test bed.

Regarding hybrid propulsion, even a fusion drive, specially any kind of drive that isn’t aneutronic, might not be a good thing to run near Earth. Not because of the danger on the surface, but because it might fry less protected satellites.

Nick Nielsen

An old pet peeve of mine: The purported wonders of the reactionless drive really amount to nothing until you invent a fuelless power source to go with it. Otherwise, the mass of the fuel you need to take is just as bad as that of the propellant. In an efficient rocket, in fact, the fuel is the propellant, meaning you don’t really “take” propellant, you just put the fuel to dual use.

As for the little robots, this is a great idea. However, I do not think teleoperation is going to be the way to go, especially not by laypeople. The key to industrial infrastructure is not the hardware, but the “software”. Currently, it exists as a huge unwieldy and disjoint collection of books, manuals, training documents, human expertise, and software. Rather than transcribe it into manuals to be used by laymen to teleoperate robots, it would be much more efficient to transcribe it into software directly executed by those robots, without human incompetence gumming up the works. It is still a huge amount of work, but almost certainly less so than creating training and operating procedures for a herd of laypeople. Crowdsourcing is all well and good, but it would be much more applicable for development of the software than its execution.

LJK:

Here’s my take on it: Before we spend another twenty comments whining and complaining about lack of interest by politicians or the public, let’s roll up our sleeves and program little robots that will eventually provide us with the means to create an industrial infrastructure in space with just a few launches.

@ljk –

I don’t see this as the only path. It is going to be a lot cheaper to adapt out civilization to adjust how we handle population growth, industrial mining and drilling, and construction. Population growth will solve itself. Mining processes can be cleaned up, and we can do more recycling. Construction can use less energy intensive materials and we can rebuild cities to be much more efficient and humane. Although I am critical of Rachel Armstrong’s specific ideas, she shows that there are other approaches to city building. We can transition to a cleaner world, with knowledge steering us away from dangerous processes. It is certainly going to be cheaper and impact more people than space colonization.

Nielsen and Rezabek have introduced the various levels of existential risk. My sense is the biggest risks are likely man made, but it isn’t clear to me that expansion into space will insulate all populations from risk.

As for getting the public interested in space, we will need to instill this at a young age. Just today I found out that none of my students in my class knew the name of the nearest star or how far away it was. They really had zero interest. We need to ENGAGE younger kids with the exploration and curiosity bug. Have materials that offer hands on relevance to space issues to stimulate questions and a desire to learn more. A few of those kids will maintain that interest.

We already have a wealth of information to use. E.g., instead of kinds making 3D landscape from USGS maps, what about using Mars maps? Models of different types of asteroids could be made and the kids explore how to deflect or destroy them. We have a enough rocket simulation software for kids to explore how best to reach planets. Embed problems in games suited for their education level. And yes, even pay for controlling a real lunar robot for the winning students.

Alternatively, one of the problems with constraining ship design to the tiny holds of the likely space transportation systems (unless a brave soul resurrects the Nova class rocket) is the huge amount of engineering required and the cramped dimensions that will inevitably result. Perhaps then it would be better to just send individual components in space, and assemble them there into larger and larger systems. We might then replace modular construction with containerization. Parts, from the earth: After all, do we need to produce ball bearings in space?

I am not just whining and complaining, I offered some realistic suggestions on how to get space exploration supported. As for the little robots everyone seems to be enamored with, if they do not get the support or funding in the first place, I fail to see how they are going to endear people to space if they cannot be built and get out there to begin with.

The real focus of this article and thread is being derailed by them. Start a new article and discussion on the little robots that might be able to save space maybe if anyone wants to. Personally they seem to be more of a distracting toy for engineers than getting to the real meat of the issue regarding how do we get into space to stay and grow.

Speaking of robots operated from Earth, Curiosity and Opportunity are exploring Mars every day, have been for years now. How often do you see news about them in the mainstream media unless they image something that looks like an alien artifact? I have talked to enough members of the public who were surprised to learn they were still functioning let alone any discoveries they were making. If they knew these machines existed at all.

I hope humanity does wake up and fix its problems on Earth, but so far I am seeing a lot of focus on trivial matters. Space may not solve everything, but it can save some of our species from doom by not leaving us all in the cradle. We also seem to need the larger cosmic perspective on our place in existence repeatedly.

Young children are interested in space, it is public education and social pressure that knocks it out of them and only a relatively few make it through that cultural strainer. So it isn’t that you just need to engage kids at an early age, you need to KEEP them interested through all the obstacles they will encounter as they get older. Society’s priorities are primarily aimed at the ground – or sports, or reality TV shows. All distractions that will serve no one any good in the long run.

@Michel Lamontagne

‘Regarding hybrid propulsion, even a fusion drive, specially any kind of drive that isn’t aneutronic, might not be a good thing to run near Earth. Not because of the danger on the surface, but because it might fry less protected satellites.’

An aneutronic drive can create an enormous amount of charged particles that can produce EMP’s, much more than a neutron rich drive.

‘…After all, do we need to produce ball bearings in space?

Due to the absence of gravitational effects magnetic/electrostatic bearings might be better.

@Alex Tolley April 30, 2014 at 22:04

‘As for getting the public interested in space, we will need to instill this at a young age. Just today I found out that none of my students in my class knew the name of the nearest star or how far away it was. They really had zero interest. We need to ENGAGE younger kids with the exploration and curiosity bug.’

So we need to look at psychology as well.

‘Have materials that offer hands on relevance to space issues to stimulate questions and a desire to learn more. A few of those kids will maintain that interest.’

Revolutions have started with a few people many times, not always for the good of humankind admittedly.

‘Embed problems in games suited for their education level. And yes, even pay for controlling a real lunar robot for the winning students.’

Just by discussing these topic amongst ourselves has produced many interesting avenues and some ideas that could be worth pursuing, the thing here is how do we continue this momentum, will it just die out when the blog closes?

Maybe we could divide up the problems with groups of people contributing some of their time to solving part of the roadmap, sort of filling stations along the great highway. Say all works on colony designs in one area, Starship engines in another and so on, then we can look at the grand vision more clearly and connect them.

We are going to need to stand on the shoulders of each other to solve this complex and ultimately rewarding task.

LJK:

We may have different ideas about what Nick’s article is about. Perhaps I was blinded by my unhealthy fixation on little robots?

In some ways we , the space advocates ( or whatever your favorite name for us would be ) behave pretty much like a splinter group on the far right or left , locked up in an all -against-all continous argument about the one and only true path to righteousness .

Or in other words , there is NO objective contradiction between different strategies to advance our common goal , as long as they dont compete directly for the same funding , which is sadly not the case ! . .. I think its great if somebody like ljk is working to get more funding and LOVE for space in general , but sadly I get the idea , that he considers my own very different ideas a complete waste of time ….

Eniac , on the other hand has a contructive opinion : Tele-operations would be too demanding for ”laypeople” , and we should concentrate on software for more automatic or autonomous robotic operations . This might proove to be true , but still I dont see any objective contradiction . In both cases there are piles and piles of work to be done in a multitude of individual detail-ares ( robot-usable software , mining tecnology, miniaturization ,geology , high temterature diferential issues , etc ) . If we could agree to divide the work up in manageable batches , we might get somewhere …. on the other hand it might be more FUN to go on arguing about who’s to drive the car !

Allow me to clarify:

I do not think the telerobotics idea is a waste of time. I think it is a good idea overall. If I did not care for it or thought it was a waste of time, I would have said so directly.

My concern is that I feel it is being focused on here to the detriment of trying to get the public interested in such things in the first place. Without the funding and support, the robots in space idea will not happen at all, or end up on a scale that will do little good for anyone. I have seen these technical discussions happen here and elsewhere before, and while they can be interesting and useful, the main point ends up being diluted or lost. And we cannot lose sight of the main point that humanity needs to be engaged and support space exploration and colonization.

I think it deserves its own article. My impression is that the point of the article we are talking in here is about building a sustainable infrastructure in space to make star vessels possible. I see robotics doing exploration as part of this but we should be discussing the wider picture. And yes, again, if we are not engaging the public and politicians about space at all, they are not going to care about little robots or starships or anything else except what they can see at the cinema or on television.

A large part of the article here is focusing on something else that I think has the potential to derail our trying to establish a permanent foothold in space: The warp drive concept. Yes, twenty years ago a real scientist wrote a paper to see if the kind of FTL propulsion depicted in Star Trek could be rendered possible: The answer is hypothetically yes, but it will require a form of matter with negative mass, which so far as we know does not exist nor would we know how to manipulate it to our purposes even if we did have it. A rather major stumbling block on the road to the stars, in my opinion. Dilithium crystals do not exist, either, so far as I know.

This new article on warp drive by someone who has a very clear grasp of the major issues involved really brings the points home here:

http://briankoberlein.com/2014/04/30/make/

Maybe there is some kind of breakthrough in warp drive just around the corner, but I also think it tends to derail us from working on real solutions to the interstellar “problem”: Trying to reach even the nearest stars in something resembling a human lifetime to return useful data on them.

The best we have right now is the Orion nuclear fission vessel; its major hangup is the issues surrounding the use of the nuclear bombs that would propel the ship, but it could be done now. Controlled fusion has yet to happen and that is considered among the “simpler” interstellar propulsion designs. Sails are attractive and technically doable but they seem to require really powerful lasers sitting in space. Antimatter is hideously expensive, minute in quantity, and potentially very fatal if not contained properly.

And these are the non-crazy-really-out-there-practically-like-magic ideas for interstellar travel! So let us focus on them if we want to see Alpha Centauri in person some day.

By the way, I am NOT saying we cannot talk about warp drives or other hypothetical methods of galactic zipping about. I just think we need more focus and work on the relatively easier and plausible methods like Orion and fusion before we aim for the USS Enterprise. Otherwise this will all remain science fiction.

@Eniac

“As for the little robots, this is a great idea. However, I do not think teleoperation is going to be the way to go, especially not by laypeople. ”

Little mining robots are hugely exciting in their capacity to deliver a enhanced rate of growth human space development, hopefully shifting us from linear to exponential growth

Maximising automation and minimising teleoperation clearly is the way to go, but I am highly skeptical that at the early stages teleoperation could be 100% eliminated – I am sure that expert tele-operators will be permanently available to intervene during risky or delicate operations at least at the beginning

@Michael

“Just by discussing these topic amongst ourselves has produced many interesting avenues and some ideas that could be worth pursuing, the thing here is how do we continue this momentum, will it just die out when the blog closes?

Maybe we could divide up the problems with groups of people contributing some of their time to solving part of the roadmap, sort of filling stations along the great highway. Say all works on colony designs in one area, Starship engines in another and so on, then we can look at the grand vision more clearly and connect them.”

Many fantastic tools exist that we can use organise to all the value that has come out of this site, both through Paul’s leadership in writing and through all the comments. Some possibilities:

-A Centauri Dreams / Tau Zero wiki

-A MOOC (Massive Online Open Course) teaching the cutting edge science of interstellar travel – yes, organisations other than universities are able to start MOOCs

-Organising ourselves through LinkedIn

I’m sure others can add to this list of suggestions

The mainstream media, at least in the USA, are profit maximizers. If there was monetizable public interest in space that was not being exploited, I think they would try harder. My guess is that the low coverage reflects public interest, compared to other “news”. Global warming gets very little media attention too, and arguably this is one of the most important issues to face humans in the C21st. 20 years ago one might have said that publishers were ignorant of what the public were interested in. Today, with news item feedback, that isn’t true. Therefore it would be almost trivial to test public interest by comparing news item feedback for space issues compared to other issues, and compare the actual media coverage.

The wider issue of public apathy to science (even active opposition) also needs effort. Why children turn away from science needs to be addressed. Is it the difficulty of the subject, lack of competent teachers, lack pf obvious opportunities, etc that is the cause, or something else? Interest in science or engineering will engender an interest in space for a sub-population of these kids.

For expensive projects like space travel, government funding is going to be needed. Educating politicians is also necessary, even if it requires them to cross ideological lines.

We’ve seen that presenting professions in a positive light can influence career choices. Movies have a strong role to play here. The spate of legal movies in the 1980’s probably stimulated the interest in being a lawyer. I’ve no doubt that “Gravity” has re-stimulated the interest in being an astronaut.

But what about scientists? Very rarely are they depicted as doing heroic things for the greater good. Mostly they are doing bad things, or their experiments lead to unforseen bad outcomes. This seems to contrast with how they were depicted in the past, either as biopics, or as the primary agent in doing good (e.g. creating a new device, neutralyzing a threat).

I find all too often that scientific discoveries are presented as though they are “marvels”. The discovery is presumed to be interesting to the reader. Rarely are such discoveries put in context or answer the question “so what?”.

The “why should I be interested?” question will have different answers for different children (and adults). Even the new “Cosmos” often leaves me impressed with the graphics but totally bored with the content. Certainly the production team do not want to answer the “why should I be interested” question – other than going with the usual “how can you not when you see the wonder of creation?”. And let me say that the crudely animated depictions of past events leave me cold – could real actors have been employed to re-enact them?

So perhaps the question we should be addressing is how to encourage children to want to approach the world with scientific mind set and reward them for doing so, all the way to their careers.

@Ole Burde April 29, 2014 at 15:09

‘When a few tons has been collected , our little friends will change tools and asemble and operate the grinding & final separation setup.’

Multi-functionally,I like it.

‘…processed using powder metalurgy . In this way the compleks componenents for whatever can be created at a much lower temperature than smelting operations.’

An electric current could be used as iron is quite conductive plus pressure, similar to how tungsten is processed. The nice thing about Nano-iron particles is that they can be alloyed easily to produce some very strong steels.

@ljk May 2, 2014 at 9:57

‘The warp drive concept. Yes, twenty years ago a real scientist wrote a paper to see if the kind of FTL propulsion depicted in Star Trek could be rendered possible: The answer is hypothetically yes, but it will require a form of matter with negative mass, which so far as we know does not exist nor would we know how to manipulate it to our purposes even if we did have it.’

We should let them dream because sometimes dreams come true, at least I hope so or the banner of this site makes no sense. But you are right about we need to stay focused on the technology we know works.

@ljk May 2, 2014 at 9:57

‘The best we have right now is the Orion nuclear fission vessel; its major hangup is the issues surrounding the use of the nuclear bombs that would propel the ship, but it could be done now.’

A fission drive (micro-implosion) could not be classified as a weapon and therefore would be exempt from the treaty.

Definition of a weapon

‘a thing —designed— or —used— for inflicting bodily harm or physical damage.’, it is an engine.

‘a means of gaining an advantage or defending oneself in a conflict or contest.’

If placed in a region where none of the fallout would return to the earth would anyone be harmed or anything be physically damaged?

@Lionel May 2, 2014 at 11:16

‘Many fantastic tools exist that we can use organise to all the value that has come out of this site, both through Paul’s leadership in writing and through all the comments. Some possibilities:

-A Centauri Dreams / Tau Zero wiki

-A MOOC (Massive Online Open Course) teaching the cutting edge science of interstellar travel – yes, organisations other than universities are able to start MOOCs

-Organising ourselves through LinkedIn

-Join or form a Spacegambit, I am joining the one in Chelmsford UK, I need to see them next Tuesday.

http://www.spacegambit.org/

-A MOOC (Massive Online Open Course) teaching the cutting edge science of NOT just interstellar travel but also the technology that will develop the infrastructure needed to build the interstellar craft.

-Perhaps a virtual reality meeting place/Online academes where questions can be asked and answered by specialists. Sort of second life quality (AI Austin?).

Once again thanks Paul, you have presented quality articles that are informative and allow us to think outside of comfort zones. I have learned a lot from others on this site and on seeing an article I am compelled to seek out answers to those articles.

@Ole Burde May 2, 2014 at 8:43

‘If we could agree to divide the work up in manageable batches , we might get somewhere …. on the other hand it might be more FUN to go on arguing about who’s to drive the car !’

Although funny it might be part of the answer why we are still stuck on earth. We are just too good at arguing rather than working together, and we are going to need to work together as this is a massive complex task!

@Michael

Thanks on the Spacegambit tip! I’m back in the UK from China later this year and plan to be in central London. Do you know whether the Hackney Hackerspace has a Spacegambit group? Would certainly also like to meet you guys in Chelmsford

@everyone discussing education

It’s a pertinent discussion and I think there are no easy answers, but I wonder whether the movement in massive online courses can be one source of hope and inspiration – have you seen the offerings of Coursera, for example, on astronomy? Although there are currently less than ten courses, the quality of the courses that I have dipped into is very high. Currently there seem to be a couple of thousands of people that are completing these courses every year, and I think it’s reasonable to expect rapid growth. Crucially many of these people will be non-astronomy majors as well as non-students – so online courses are massively opening up education in all sorts of areas and this includes space

I was really very impressed from what I saw of the “Introduction to Astronomy” MOOC on Coursera by Duke University – although I only saw the first couple of weeks, Ronen Plessor who teaches the course I found to be brilliant and passionate and has put so much into making it. Will do my best to complete it on a future iteration

Another Coursera class is the “Imaging Other Earths” course from Princeton that is ending this week. People who sign up for this course now (completely free) will have continuous access to these videos, those who don’t will have to wait for another iteration, probably next year

@Lionel May 3, 2014 at 12:16

‘Do you know whether the Hackney Hackerspace has a Spacegambit group? Would certainly also like to meet you guys in Chelmsford’

Unfortunately it does not look like it, they do work with robots a bit and biology, maybe you could ask about alien biology possibilities and point them toward AC, they may be able to answer some questions on here.

Every Tuesday, 19:00 – Robotics

Every Wednesday, 19:30 – Biohacking catch-up

https://wiki.london.hackspace.org.uk/view/London_Hackspace

But there is nothing stopping someone starting or a least broaching the question of forming a Spacegambit, part of the roadmap, Education!

The one in Chelmsford is a Makerspace and it is small, but I will try to persuade them to build one common project with a space theme using all their skill sets, spread the word sort of idea, as I have access to a fair amount of electronics and instruments that could help them.

Lionel:

You are right. However, I think that these expert operators will not be teleoperating on the moon, but rather take care of their not-quite-finished robots right inside a terrestrial workshop. It is hugely easier and cheaper to develop initial prototypes of self-assembling robots right here on Earth, where we can stand by with the screwdriver anythime it is necessary. More importanly, a failure means a lost day at the shop rather than a lost million dollar rocket launch. Funding for these kinds of developments could come right out of an average hobbyists budget, or a kickstarter project in more ambitious cases.

Self assembling robots would have many non-space applications, anyway. Think of self-maintaining solar power farms in the desert that make solar cells from sand. Even for late-stage space related developments it may in many cases be easier to utilize a vacuum chamber and synthetic moondirt rather than the real thing. Actual space comes into play only when most of the kinks have been worked out and success is likely on the first launch.

If I understand LJK directly, he would have this forum focus on advocacy rather than technical discussions. The latter, he appears to think, are nice and dandy, but not nearly as important as the crucial advocacy work we have to do.

This is directly opposite to my own convictions, truth be spoken. I see very little value in discussing advocacy, especially when around here it amounts to preaching to the choir. I frequent this blog specifically because of the excellent science and technology reports and discussion. I will lose interest if the place gets turned into an advocacy echo chamber.

Is there a ”we” ?

From early childhood Space and anything connected to it has been an important part of my life . Until now , it has mostly been reading , learning and talking about it , because as isolated individuals only a very few lucky , rich , exeptionally gifted or well connected people has any chance of doing any meaningful work .

My idea is , that it might be possible to change this situatiion , by looking at the thousands of well-motivated volunteers like myselv as a valuable ASSET , a high-value raw material from which something extreemely valuable might be created .

In other words , it seems that ” we ” need an ” Organisation” in order to become WE , even if I dont yet understand at all what kind ,or where or how or when…So , just like any other problem related to space (last thing I cleaned out was Vacum-welding) , I’me goin to read up on it , starting from the buttom , and optimistic about reaching the top .

Alex Tolley said on May 2, 2014 at 15:41:

“We’ve seen that presenting professions in a positive light can influence career choices. Movies have a strong role to play here. The spate of legal movies in the 1980?s probably stimulated the interest in being a lawyer. I’ve no doubt that “Gravity” has re-stimulated the interest in being an astronaut.”

I have my doubts about Gravity turning people on to space. If anything I think it may have made them eve more reluctant to journey into the Final Frontier.

From the start of the film we are told how dangerous space is, that it is no place for a human life form, and one screw up and you are dead within seconds. Then we have Sandra Bullock’s character who is clearly unhappy and unenthusiastic from the get-go and who goes through a ridiculous string of spacecraft mishaps which she somehow survives nevertheless (the HST, one Space Shuttle, two Soyuz, and two space stations are destroyed during this film, along with every astronaut except Bullock).

At one point she says “I hate space” and who can blame her after her ordeal, but that is the phrase that will resonate in the audiences’ minds. At the end she returns to Earth and it is clear that is where she – and the audience – should really belong according to the film.

So maybe Gravity did encourage a few people to become astronauts, once they vaulted the dour attitude to being up there and all the death and destruction, but I bet it turned away a lot more. Apollo 13 was also about a disaster in space – a real one – but at its core was fortitude, hope, and a plea for us to return to the Moon.

All these discussions are quite interesting in their own right, but I wonder if perhaps there is interest in whether a new approach might be reasonably attempted.

It would seem to be a twofold problem: approaching the government concerning space issues and pigeonholing the proper officials who make decisions regarding space policy. Pigeonholing means being influential and also arm-twisting and being persuasive. In short you need a person who is a LOBBYIST a dirty word if there ever was one in the government but in this day and age an absolute necessity. Now lobbyist do not like to work for free because they have their own lives to take care of and that means that something called money is going to be required to be needed.

This is where the rubber meets the road, what we call the second problem; to get money you either have to have somebody who’s already got money or you need to get the money yourself. Now from what I understand there is now a website in which you put forth a cause and essentially ask for solicitations to fulfill your goal(s). I honestly can’t recall what the website is called but it’s up to the individual who opens a plea to go ahead and make a persuasive argument as to why people should donate. What do y’all think ??

@ljk You may be right about “Gravity”. What I saw as an astronaut solving problems to get home, but it may be that people take home the message that we should stay home. And yes,”Ap0ollo 13″ did end with those stirring words about going back to the moon, despite the setbacks and danger. What happened to that spirit of adventure?

ljk : the resulting vektor-of-influence in almost anything SERIOUS made in Hollywood in the last 20 years , can only be described as anti-space , anti-tecnology , anti- almost everything eccept som confused and extremely selective ideas concerning ”human rights ” …Only when departing clearly from reality (like Spiderman and friends !) is it possible in the Post-Everything universe of Hollywood to create anything but fanatic politic correctnes .

Remember ”Avatar” …that was all about inserting the ideals of Post-Imperialistic Guiltfeelings to the next generation .

Eniac said on May 3, 2014 at 23:22:

“If I understand LJK directly, he would have this forum focus on advocacy rather than technical discussions. The latter, he appears to think, are nice and dandy, but not nearly as important as the crucial advocacy work we have to do.”

NO. That is a complete misinterpretation of what I was saying. And I thought I made myself pretty darn clear earlier.

I have NO issue with technical conversations here. They are important. Plus it would be incredibly stupid of me to say otherwise here because yes I know the conversations would dry up in short order.

I was trying to say that the little robots conversation in my view was taking away from what this article and thread are about. Not that even that idea is bad, but that everyone would start focusing it rather than what could be done to get us to stay in space permanently with the kind of infrastructure needed to make a starship happen.

No one has to listen to me if they want to, I am just stating my view. But please do NOT misinterpret me, especially after I have had to clarify myself more than once here.

You then said:

“This is directly opposite to my own convictions, truth be spoken. I see very little value in discussing advocacy, especially when around here it amounts to preaching to the choir. ”

That is why I was saying earlier that folks here should be taking the space advocacy messages to the general public and politicians. I even offered several ways it could be done for those technical folks who are not comfortable teaching directly to people.

Seriously, how was I misread so much? Am I that poor a communicator? Or was it on purpose to keep the starship discussions here strictly technical? Which in my view will make the space groupies happy but ensure that the masses do not care or support such endeavors.

There is room for both. It is necessary.

@Eniac

‘If I understand LJK directly, he would have this forum focus on advocacy rather than technical discussions. The latter, he appears to think, are nice and dandy, but not nearly as important as the crucial advocacy work we have to do.’

I don’t think LJK meant it that way, I think it was more out of frustration with the system more than anything else, to me anyway.

The whole objective of Space needs looking at, from little robots to interaction with Politician’s. We need to divide the problem up with the people who are good at certain tasks doing their part and bringing it together.

If we ask a load politicians for a load of money to go to the moon they will say why? Now if we build robots and with the aid of private enterprise do our part getting to the moon they may put the their hands in the ‘publics’ pocket and provide the money. But we have to show that we want to go into space permanently and that will require getting the public on our side.

And as LJK wrote ‘There is room for both’ and he is right.

As time passes by , the Apollo-era can bee observed more objectively . The good news is that an almost-miracle happened , the bad news is that it almost certainly won’t happen again . What COULD happen again is something very diffent ,more like the creation of a new social mecanism which would be dedicated to a hands-on advancement of spaceprojects in general , and human spacetravel in particular . ( Amateur astronomy has already shown a small very specifik gimpse of what can be achieved in this direction) .

It is not necesary to be a democratic majority in order to gain influence , all it takes is to have a few percent of well motivated people with an effective organisation . This does not meen that ”space advocacy” in the normal definition of the word has lost importance , it only sugests that it can not sucseed alone .

This article is relevant to teh education idea:

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2504/1

LJK: I apologize for misreading you that much. I am glad that you were not trying to say what I misheard you say, and I am relieved that we can keep the focus on science and technology around here that has made this blog so interesting and different from what else there is out there.

Here I am, excited to talk about industrial space infrastructure (involving little robots, of course), and we are reviewing movies instead. Sigh. ;-)

Alex Tolley said:

” You may be right about “Gravity”. What I saw as an astronaut solving problems to get home, but it may be that people take home the message that we should stay home. And yes,”Ap0ollo 13? did end with those stirring words about going back to the moon, despite the setbacks and danger. What happened to that spirit of adventure?”

Between the making of Apollo 13 and Gravity, America walked into two disastrous wars and went through the global financial crises – meanwhile China has risen rapidly. My opinion is that Hollywood is just tapping this national loss-of-mojo

That probably sounds bleak, but the last 5 or 6 years have been. Things seem to be relatively picking up for western nations now though, and if they do then I think the adventure spirit will rise alongside

Ole, you may be right that it only takes a dedicated and resourceful select group of people to get the job done in terms of a permanent and expanding human presence in space. That may in fact be the essential ingredient to literally get things off the ground and into the Final Frontier.

My concern is that we better hope this select group who is calling all the shots has the majority of folks’ best interests in mind once things get going, or that they will then allow others to have a say and sway. What I fear is something like a few corporations monopolizing space and claiming turf and setting prices. Even more problematic, if they are driven by profit as the bottom line, they could dismiss or ruin what would be of incredible value to a scientific space expedition just because they don’t see any money in it.

It probably will take private enterprise to get us up there permanently – either that or a government which appreciates what politicians and military leaders once knew decades ago about the advantages of the High Frontier.

My concern is that space will become primarily theirs and everyone else will either have to abide by their rules or stay stuck on Earth.

You can say that people often rebel whenever a leadership becomes too big for its britches, but will it work the same in space, where there is are few choices when it comes to staying alive?

There is another question: How many space planners have seriously thought about how a society might evolve in space? Including the possibilities for totalitarian regimes and rebellion?

ljk : My own worries are of a somewhat differet kind . They basicly concern the possibility that mankind wil be stuck o earth having wasted the window of opportunity which started from the apolo-era , and which might end when rawmaterials will start running out , leading to the end of cooperation between major powerblocks ,and perhaps to everyboddy shooting down each others satelites and spacecraft . Anti-missile systems has now become a mature tecnology , and mass production (like the ” iron dome” system) are already making it afordable on a global scale . Such systems were developped for a defencive role , but could also be used to attack anything mooving at high speed . With minor modifications they might prevent anybody from launching anything of a much higher value than the attacking missile itself .

Anyhow , the window of opportunity might not last forever . Human history shows that many cultures ALMOST reached to the point where the scientific-tecnologic breakthrough became possible ,only to vaste the window of opportunity by not realising its importance .

Only once in history was this opportunity NOT wasted , and from this single exceptional event we cannot conclude anything .

Time might not be on our side as much as we would like to believe , and therefore almost ANY kind of social structure or political system which is capable of advancing spaceflight in a decisive way , will be a minor setback compared to what could happen later without it .

Ole, I also share that “window of opportunity” concern. Many people continue to act like our current civilization and its pace of resource exploitation and land grabbing can continue indefinitely. Even if the human population stabilizes at “just” 9 billion in 2050 as some predict (and how exactly will this come about I must ask them?) those who do exist will not stop consuming resources.

Earth is a finite place no matter what they wish or believe otherwise. It and/or Gaia also seem to have some self-corrective measures in place to handle species that get out of hand. If that fails and we do not further develop our space programs, then space will eventually provide a nice big rock to clear the deck.

As I said before, I do not expect space colonization to solve all our problems. What I do see it doing at the least is saving some of our species from extinction by not having all our eggs in one basket, as the phrase goes. If we do this in time, as you have already pointed out.

Speaking of space infrastructures, here is an article on Solar Power Satellites that may be of interest:

http://www.wired.com/2014/04/solar-power-satellites-a-visual-introduction/

I’m not as pessimistic about global population pressure and resources as others. While it is true that the Earth is finite, there is plenty of scope to increase populations and even resource use. Populations are quite sparse over the land area of a country, while cities are typically 3 orders of magnitude denser. While I don’t envisage Earth becoming like Asimov’s Trantor, our ability to manufacture living space by building multi-level structures will allow us to accommodate larger populations comfortably as far as shelter goes.

Food production might seem like the greater problem, but it suffers from the same thinking. Plants use only a fraction of the available sunlight and crops are constrained by seasonal growing periods. Vertical farming and artificial light can increase conventional crop growth, and we have barely started to explore factory food production from bioengineered organisms. It won’t be cheap, and it might be like “soylent” to some extent, but we can probably increase food production by these methods, as well as make food healthier to eat.

Energy production might currently look like a land grab, especially for the sparring over Arctic oil and gas, but we know how to generate carbon free energy in abundance, far beyond our existing energy consumption.

Other resources that periodically get worried about as running out don’t. We should have learned something from Simon’s winning bet with Ehrlich by now.

If we can sustain economic growth on this planet for even another couple of centuries, it is likely that our global wealth will easily support a vibrant use of space resources and associated exploration, both robotic and human – if we want to.

Of course it could all go to pieces with a civilization collapse or deep retrenchment. If that happens, I’m not sure that a near future off world colony could sustain itself and would find itself failing like the Norse Greenlanders when the trade ships ended as the climate cooled.

ljk : Peter Glasser’s ideas has no REALISTIC meaning without combining them with Gerald O’Neils adition of a mass-launcer , shooting out moon-materials to be caugt and processed i space . There is no way short of warp-factor stuff to build a cost efficiet energy sattelite with earth materials only.

The only other way would be to use asteroid materials , but this is farther into the future than the moon option . This is EXACTLY why we need to focus on robotic mining operations on the moon , because if and when locally produced bulk material become avaiable on the moon , there is a chance that a major corporation ( like GE ) would start considering to make a medium sized investment in a mass-launcer , leading to a wider group of corporation making the big-money- gamble of the first comercial energy sattelite.

Building a bridge to space solar power for terrestrial use

A long-running challenge to the concept of space-based solar power is the high costs inherent in generating it versus terrestrial alternatives. David Dunlop and Al Anzaldua examine approaches to develop key technologies and address the cost issue through a stepping-stone approach.

Monday, May 12, 2014

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2509/1

ljk : Try to google ”Micowawe Transmission” or related sujects , and you will realise how depressingly litle has actualy been DONE in the field . Lots of hopefull descriptions of wide ranging future scenarios , but very litle actual work . At this point nobody can say if energy transmission through 50km of atmosphere will ever do better than 30-50% efficiency , which is probably why nobody is jumping to invest in the area . The main problems have been known since 1926 , and nothing much has happened since then .

Life in space is impossible

Several recent movies have provided a negative view of space, including Gravity’s opening message that “life in space is impossible.” Dwayne Day compares those messages with the promise of an upcoming film, Interstellar, and the challenges of getting a positive space message out to the public.

Monday, May 19, 2014

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2516/1

To quote:

One of the biggest and most praised movies of 2013 was Gravity. The film stormed the box office and received rave reviews and numerous Oscars, including one for best director. Although astronauts and spaceflight experts stumbled all over themselves to discuss the technical inaccuracies in the movie while praising it for its visual and excitement, what was lost in all the chattering is that Gravity is one of the most anti-space movies to come along in a long time. It may have done just as much damage to NASA’s image as the frequent reports during the October government shutdown that NASA was the “least essential” agency, based upon the determination that 97% of its employees should stay home.

And…

The pro-space movement has no single voice and no single message. At best it is stagnating, at worst it is losing ground. At the very least it needs to present a more promising and uplifting message to a much broader audience. It needs fewer arguments about rocket engines and less infighting and sniping and NASA-bashing. What it really needs is a positive message and a positive, likeable messenger, and a major venue, like a big budget Hollywood movie, to battle the space-is-irrelevant message that seems to be taking hold in the culture.

We must probably start thinking about what CAN actually be done by a few determined people with limited means.

Now the ISEE-3 Reboot project has shown that a few determined individuals can get a space project funded through Kickstarter, and even though their craft doesn’t seem to have fuel left for maneuvering, the project is continuing to do science, making the most of what they have.

Now what are the chances of some similarly determined individuals getting a crude type of solar sail to hitch a ride on a SpaceX launch, and start getting some experience with maneuvering that sail around in LEO? I am sure one could crowd-source such a project through Kickstarter?

Once that is done, or at the same time, could a team of similarly determined individuals not start working (here on terra firma) on a small programmable robot like the ones talked about in the comments above? And once a working prototype is manufactured, it could similarly hitch a ride to LEO aboard a commercial launch, along with, say, some spare controller boards, electrical motors and such, could it not?

Once you have these two projects in LEO, the sail could go and dock with the robot, with the help of the manipulator arm or two that the robot is bound to have. And then the sail could be used to start dragging the robot up, up and away. It will be slow, but it will get to escape velocity eventually.

Now the big snag with this idea is of course that, once you get to the Moon with this duo, there is no safe way to actually LAND the robot on the surface of the Moon. But then of course, who said you need to land it on the Moon?

Why not aim it for one of these near Earth asteroids, the smaller the better, that are in approximately the same orbit as Earth, and just “dock” with it? The landing will be much much easier without the Moon’s 1/6g of gravity getting in the way.

And then you can use that robot to mine the asteroid, see if you could use it to build a bigger robot, use that to build an even bigger robot, and maybe use the solar sail to get one of these robots to another asteroid and so on and so on. You get the picture.

Come to think of it, another advantage of landing your robot on an asteroid is that you don’t have engineer your robot to deal with this two weeks of hellish heat followed by two weeks of hellish cold that you get on the Moon. A “day” on an asteroid is probably just a few hours, so no huge temperature differentials.