Are we alone in the universe? Nick Nielsen muses on the nature of the question, for the answer seems to depend on what we mean by being ‘alone.’ Does a twin of Earth’s ecosystem though without intelligent life suffice, or do we need a true peer civilization? For that matter, are we less alone if peer civilizations are widely spaced in time and space, so that we are unlikely ever to encounter evidence of them? And what of non-peer civilizations? SETI proceeds while we ponder these matters, a search that Nick sees as a priority because of the disproportionate value of an exterrestrial signal. Like Darwin in the Galapagos, we push on, collecting data in a quest that is without end. It’s a prospect Nick finds invigorating, and so do I.

by J. N. Nielsen

One of the great questions of our time is, “Are we alone?” Even though it is, for us, an existential question that touches upon our cosmic loneliness, it is, at the same time, a scientific question, as befits our industrial-technological civilization, driven as it is by progress in scientific knowledge. Because it is a scientific question, it hinges upon empirical evidence, but this empirical evidence must be placed in a theoretical context in order to make it meaningful. (Anecdotal evidence is not going to resolve the question.) Empirical evidence provides the observational content of a theory; formal concepts provide the theoretical framework of a theory. Neither in isolation constitutes a science (with the possible exception of the formal concepts of mathematics), but a given science may place more emphasis upon the empirical or the formal aspects of a theory. I will try to show below how Fermi’s paradox can be approached primarily formally or empirically.

Clarke’s tertium non datur

There is an understandable human desire to answer a question as clear as “Are we alone?” with an equally clear yes-or-no answer, but it is not likely that this will be the case. What we discover as we explore the cosmos is likely to be unfamiliar, unprecedented, and perhaps unclassifiable. Or, at least, the unclassifiable will be part of what is found, along with that which fulfills our expectations. It will be what challenges our expectations, however, that will shape the development of our thought and force us to revise our theoretical frameworks.

The yes-or-no formulation of the question of a cosmic loneliness I have elsewhere called Arthur C. Clarke’s tertium non datur, following Clarke’s well-known line that, “Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying.” [1] The logic of this compelling assertion seems undeniable, until one studies logic and one finds that the law of the excluded middle to which Clarke appeals (and which is also known as tertium non datur) is controversial, and that intuitionistic logics do without the law. Making the claim that Clarke makes, then, constitutes a subtle form of Platonism, and a constructivist or an anti-realist will reject this claim. Thus a formal approach to the question “Are we alone?” becomes, in part, a logical question rather than a question of empirical research.

From an empirical point of view, only a little reflection will show that the question “Are we alone?” is not likely to be satisfyingly answered in yes-or-no terms. If we find simple (single-celled) life below the surface of Mars or in the oceans of Europa, will we say that we are no longer alone in the cosmos? Apart from evidence that life can independently emerge in the universe, thus making it all the more likely that a peer civilization exists somewhere in the Milky Way, exobiological bacteria will not satisfy our desire for fellow beings with whom we can communicate as moral equals.

If we find a world of complex life, perhaps even a complex biosphere consisting of multiple diverse biomes, but no sentient, intelligent life, will we say that we are no longer alone? From a biological point of view, a twin of Earth’s ecosystem would mean that Earth is no longer alone, but that still does not rise to the level of finding conscious, communicative beings in the context of a peer civilization. I will admit without hesitation, however, that for some among us such a discovery would carry with it the feeling of cosmic companionship; the feeling of what it means to be alone in the universe is subject to individual variability, and therefore disagreement.

It seems likely to me that most human beings are only going to feel we are not cosmically isolated if we find a peer civilization, that is to say, another civilization roughly technologically equivalent to our own, being the work of biological beings who have converged upon a technology commensurate with our own, or some technology near that level. However, we are not yet prepared to say what a peer civilization is, because we cannot yet say what our own civilization is. We have no science of civilization, and therefore no way to employ scientific concepts to classify, compare, or quantify civilizations. [2] This does not mean that we have no idea whatsoever what civilization is, or what our civilization in particular is, only that these ideas cannot be called scientific.

The law of trichotomy for exocivilizations

Elsewhere I have discussed what I called the law of trichotomy for exocivilizations, which is the straight-forward observation that another civilization, presumably a peer civilization, must, in relation to our own civilization, appear before our civilization, during the period of our civilization, or after our civilization. [3] The dichotomy between being alone or not alone in the cosmos, and the trichotomy of another civilization coming before, during, or after our own civilization, are formal ideas based on conceptual distinctions. In other words, they are not ideas based on empirical evidence, and so they derive from the theoretical context employed to interpret empirical evidence.

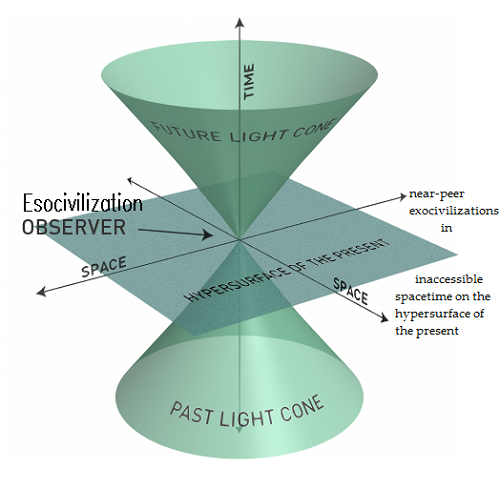

While the law of trichotomy for exocivilizations is ideally applicable, in practice it runs into relativistic problems. Relativity means the relativity of simultaneity, so that the absolute simultaneity implied by an ideal interpretation of the law of trichotomy (as when we apply the law to real numbers) does not work if the simultaneity in question is the punctiform present [4]. If, however, we allow a little leeway, and grant some temporal “width” to the present, we could define a broad present in which peer civilizations exist simultaneously, but this width would rapidly exceed the age of industrial-technological civilization as we attempt to expand this broadly-defined present in the galaxy (much less the universe). Thus, what we will not find are peer or near-peer civilizations existing simultaneously with our own, unless scientific discoveries force major changes in relativity theory or something like the Alcubierre drive proves to be a practicable form of interstellar transportation.

The act of traveling to the stars in order to seek out peer civilizations involves a lapse of time both on our home planet and on the homeworld of a peer civilization. The kind of temporally-distributed civilization that I described in Stepping Stones Across the Cosmos could constitute one form of temporal relations holding among mutual exocivilizations: the overlapping edges of two or more temporally-distributed civilizations may come into contact, but given that both civilizations are temporally distributed, the home world of these civilizations can never be in direction contact, and any radio communication between them might require hundreds, thousands, or millions of years—periods of time probably well beyond the longevity of our present civilization.

Using formal concepts in the absence of observation

The examples given above of Arthur C. Clarke’s tertium non datur and the law of trichotomy for exocivilizations seem to point to the limitations of formal conceptions in the face of the stubborn facts of empirical observation, but formal concepts can prove to be a powerful tool in the absence of empirical observation, when these observations require technologies that do not yet exist, or which have not been built for institutional or financial reasons.

One of the most obvious ways in which we are now limited in our ability to make empirical observations is that of imaging exoplanets. We know that this technology is possible, and in fact we could today build enormous telescopes in space, such as a radiotelescope on the far side of the moon, shielded from the EM spectrum radiation of Earth, and possibly sufficiently sensitive to detect the passive EM radiation of an early industrial-technological civilization. That we do not do so is not a matter of scientific limitations, and not even a matter of technological limitations. We have the technology now to do this, though there would be many engineering problems to be resolved. The primary reason we do not do so is lack of resources.

Because of our inability at present to see or to visit other worlds, we have no empirical data about life or civilization elsewhere in the universe. It is sometimes said that we have only a single data point for life, and scientific extrapolation from a single data point is unreliable, if not irresponsible.

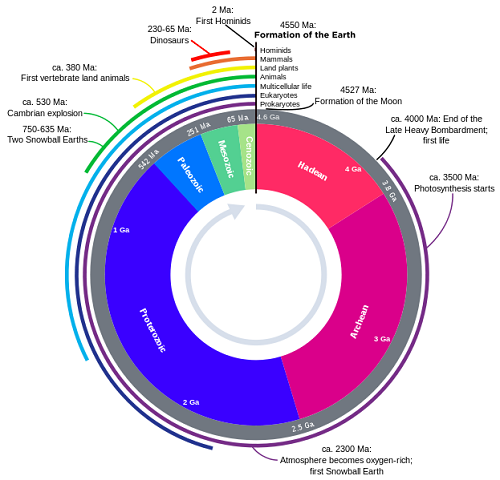

While a merely formal grasp of life and civilization may seem a pale and ghostly substitute for actual empirical data, in the absence of such empirical data a formal understanding may allow us to extract from our own natural history, and the history of our civilization, not one data point but many data points. If we can take a sufficiently abstract and formal view of our own world, that is to say, if we can rise to the level of generality of our conceptions that attends only to the structure of life and civilization on Earth, we may be able to derive a continuum of historical data points from the single instance of life on Earth and the single instance of human civilization.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Spatio-temporal distribution of life in the universe

Life on Earth taken on the whole constitutes a single data point, but the natural history of life on Earth reveals a continuum of data points. The temporal distribution of the natural history of life on Earth – if this is at all representative of life simpliciter – can be roughly translated into the spatial distribution of life on Earth-like planets in the universe, on the assumption that Earth-like planets are continuously in the process of formation.

In more detail:

1. The universe is about 13.7 billion years old.

2. The Milky Way galaxy may be nearly as old as the universe itself – 13.2 billion years, by one estimate [5], which means that, in one form or another, the Milky Way has persisted for about 96 percent of the total age of the universe.

3. Population I stars, with higher a metallicity consistent with the formation of planetary systems with small, rocky planets are as much as 10.0 billion years old [6], or have existed for about 73 percent of the total age of the universe – almost three-quarters of the age of the universe.

4. The Earth formed about 4.54 billion years ago, so it has been around for 33% of the age of the universe, or about a third.

5. Life is thought to have started at Earth about 4.2 to 3.8 billion years ago, so life has been around for 28 percent of the age of the universe, or more than a quarter. Life started at Earth almost as soon as Earth cooled down enough to make life possible. Although life started early, it remained merely single-celled microorganisms for almost two billion years before much more of interest happened.

6. Eukaryotic cells appeared about 2 billion years ago, for a comparative age of 15% of the age of the universe.

7. Complex multicellular life dates from about 580 million years ago (from the Cambrian explosion), so it has been around for 4 percent of the age of the universe.

8. The mammalian adaptive radiation following the extinction of dinosaurs (and thereby giving us lots of animals with fur, warm blood, binocular vision, sometimes color vision, proportionally larger brains necessary to process binocular color vision, and thus a measure of consciousness and sentience) began about 65 million years ago, and thus represents less than a half of one percent of the total age of the universe.

9. Hominids split off from other primates somewhere in the neighborhood of five to seven million years ago, and thereby began the journey that resulted in human beings, which possess a greater encephalization quotient than any other terrestrial species. This period of time represents about half of a thousandth of one percent of the age of the universe. [7]

10. The earliest forms of civilization emerged about 10,000 years ago, roughly simultaneously starting in the Yellow River Valley in China, the Indus River Valley, Mesopotamia, and what is now Perú (with a few other scattered locations). Industrial-technological civilization – the kind of civilization that can (potentially) build spacecraft and radiotelescopes – is a little more than 200 years old, which is too small of a fraction of one percent to bother calculating. This is the proverbial needle in the cosmic haystack.

We can recalculate these percentages specific to the age of the Earth (rather than to the age of the universe entire), so that 88 percent of the Earth’s age has included life, 44 percent has included eukaryotic cells, 13 percent has included complex multicellular life, 1.4 percent has included mammals of the post-K-Pg extinction event, 1.5 thousandths of a percent has included hominids, and a miniscule fraction of a percent of the total age of Earth has included civilization of any kind whatever.

Given a small, rocky planet in the habitable zone of its star (i.e., given an Earth twin, which recent exoplanet research suggests are fairly common), such a planet is 88 percent likely to have reached the developmental stage of rudimentary life, 44 percent likely to have reached the stage of eukaryotes, 13 percent to have progressed to something like the Cambrian explosion, and a little more than one percent may have produced animal life of a rudimentary degree of sentience and intelligence. [8] If we take current estimates of Earth twins of 8.8 billion in the Milky Way galaxy alone [9], only somewhat more than a million would have advanced to the stage corresponding to early hominids on Earth – and these million must be found within the 300 billion star systems in the galaxy.

The data points that we can extract from our own natural history leave us almost completely blind as to our future, and therefore equally blind in regard to civilizations more technologically advanced than our own. We have no experience of the collapse of industrial-technological civilization, so we have no evidence whatsoever that would speak to the longevity of such a civilization. [10]

Image: Stromatolites in Shark Bay, photograph taken by Paul Harrison. Is this what most habitable planets in the galaxy look like? Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

[http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Stromatolites_in_Sharkbay.jpg]

A universe of stromatolites

Of course, it is misleading to speak of taking an Earth twin at random. The universe is not random. [11] Like the Earth itself, it exhibits a developmental trajectory (sometimes called “galactic ecology” or “cosmological ecology”), so that any particular age of the universe is going to yield a different percentage of Earth twins among the total population of planets in the universe. Someone versed in astrophysics could give you a better number than I could estimate, and could readily identify the period in the development of the universe when Earth-like planets are likely to reach their greatest number, though we know from our own existence that we have at least passed the minimal threshold.

Despite the fact that my estimates are admittedly misleading and probably inaccurate, as a rough-and-ready approach to what we are likely to see when we have the technology to observe or to visit Earth twins, these percentages give us a little perspective. We are more likely than not to find life. Life itself seems likely to be rather common, but this is only the simplest life. We may live in a universe of stromatolites – i.e., thousands upon thousands of habitable worlds in the Milky Way alone, but inhabited only by rudimentary single-celled life [12]. Maybe a tenth of these worlds will have seas churning with something like the equivalent of trilobites, and possibly one percent will have arrived at the stage of development where many species have relatively large brains, precise vision (something like binocular color vision), and limbs capable of manipulating their environment. In other words, possibly one percent of worlds will have produced species capable of producing civilization. The chance of finding the tiny fraction of a percent of these species that go on to create an industrial-technological civilization (and therefore could be considered a peer civilization to our terrestrial civilization) remains vanishingly small.

In a universe of stromatolites, are we alone or are we not alone? The answer is not immediately apparent, and that is why I said that the tertium non datur form of the question, “Are we alone?” is not likely to be given a satisfying answer.

Image: A caricature of Darwin collecting beetles by fellow young naturalist Albert Way. Credit: The Darwin Project. Credit: The Darwin Project.

A journey to distant worlds

From the above considerations, I consider the search for a peer civilization to be like the proverbial search for a needle in a haystack. But it is still a search that is well worth our while – as well as being worth our investment. If you are personally invested in a search for a particular needle in a haystack, you are likely to continue the search despite the apparently discouraging odds of being successful. We are, as a civilization, existentially invested in the search for a peer civilization, as a response to our cosmic loneliness. For this reason if for no other, the search for a peer civilization is likely to be pursued, if only by a small and dedicated minority.

Far from suggesting that the difficulty of a successful SETI search means that we should abandon the search, I hold that the potentially scientifically disruptive effect of a SETI search that finds an extraterrestrial signal would be so disproportionately valuable that SETI efforts should be an integral part of any astrobiological effort. The more unlikely the result, the greater would be the falsification of existing theories upon a successful result, and therefore the more we would have to learn from such a falsification. This is the process of science. A single, verifiable extraterrestrial signal would give a satisfying answer to the “Are we alone?” question, since a single counter-example is all that is needed.

Anticipating responses that I have encountered previously, I should mention that I do not find this point of view to be in the least depressing or discouraging. A universe of stromatolites, with the occasional more complex biosphere thrown into the mix, strikes me as an exciting and worthwhile object of exploration and scientific curiosity. With so many worlds to explore, it is easy to imagine the re-emergence in history of the gentleman amateur natural historian, which is how Darwin began his career, and some future Darwin collecting the extraterrestrial equivalent of beetles might well make the next major contribution to astrobiology. Darwin wrote, “…it appears to me that nothing can be more improving to a young naturalist, than a journey in distant countries.” [13] He might as well have written, “…nothing can be more improving to a young naturalist, than a journey to distant worlds.”

If we add to this prospect (to me a pleasant prospect) the possibility of a few extraterrestrial civilizations lurking among the stars of the Milky Way, at a pre-industrial level of development and therefore unable to engage with us until we stumble upon them directly [14], I cannot image a more fascinating and intriguing galaxy to explore.

Notes

[1] Quoted in Visions: How Science Will Revolutionize the Twenty-First Century (1999) by Michio Kaku, p. 295.

[2] I take these three kinds of scientific concepts – classification, comparison, and quantification – from Rudolf Carnap’s Philosophical Foundations of Physics, section 4; cf. my post The Future Science of Civilizations. We can classify, compare, and quantify energy usage, and it is this approach that gives us Kardashev civilization types; we can also classify, compare, and quantify information storage and retrieval, which gives us the metric proposed by Carl Sagan for giving a numerical value to civilization, but I take these to be reductive approaches to civilization, and therefore inadequate.

[3] The law of trichotomy for exocivilizations is simply a particular example of the law of trichotomy for real numbers, though applied to civilizations in time – time being a continuum that can be described by the real numbers.

[4] The idea of the punctiform present is that of the present moment as a durationless instant of time that is the unextended boundary between past and present. Note that the idea of the punctiform present is an idealization, like Clarke’s tertium non datur and the law of trichotomy of exocivilizations; as such it is a formal conception of time, and not an empirical claim about time. Like the distinction between pure geometry and physical geometry, we can distinguish between pure time, which is a formal idea parallel to pure geometry, and physical time.

[5] Cf. the Wikipedia entry on metallicity: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metallicity

[6] “Populations of Stars” http://www.astronomynotes.com/ismnotes/s9.htm

[7] I am employing the older distinction between primates and hominids. It has become commonplace in recent anthropological thought to introduce a new distinction between hominids and hominims, according to which hominids are all the great apes, including extinct species, and hominims are all human species, extinct and otherwise; This new distinction adds nothing to the older distinction. Moreover, from a purely poetic point of view, “hominim” is an unattractive word with an unattractive sound, with a series of insufficiently contrasting consonants (especially in contradistinction to “hominid”), so I prefer not to use it. I realize that this sounds eccentric, but I wanted my readers to be aware, both of the distinction and my reasons for rejecting it.

[8] I leave it as an exercise to the reader to reformulate my developmental account of the emergence of industrial-technological civilization on Earth into the more familiar terms of the developmental account implicit within the Drake equation.

[9] A recent study was widely publicized as predicting that 8.8 billion Earth-like planets are to be found in the habitable zones of sun-like stars in the Milky Way galaxy. “Prevalence of Earth-size planets orbiting Sun-like stars,” Erik A. Petigura, Andrew W. Howard, and Geoffrey W. Marcy doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319909110 (http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2013/10/31/1319909110)

[10] I wrote, “almost completely blind,” instead of, “completely blind,” as there obviously are predictions that can be made about the future of industrial-technological civilization, and some of these are potentially very fruitful for SETI and related efforts. More on this another time.

[11] The universe is neither random nor arbitrary; Earth is not random; life, intelligence and civilization are not random. Neither, however, are they planned; the order that that exhibit is not on the order of conscious construction anticipating future developments. It is one of the great weaknesses of our conceptual infrastructure that we have no (or very little) terminology and concepts to describe or explain empirical phenomena that are neither arbitrary nor teleological. We have, perhaps, the beginnings of such a conceptual infrastructure (starting with natural selection and moving on to contemporary conceptions of emergentism), but this has not yet pervasively shaped our thought, and it remains at present sufficiently counter-intuitive that we must struggle against our own cognitive biases in order to consistently and coherently think about the world without reference to teleology.

[12] According to Wikipedia, stromatolites are, “layered bio-chemical accretionary structures formed in shallow water by the trapping, binding and cementation of sedimentary grains by biofilms (microbial mats) of microorganisms, especially cyanobacteria. Stromatolites provide the most ancient records of life on Earth by fossil remains which date from more than 3.5 billion years ago.” I employ stromatolites merely as an example of early terrestrial life sufficiently robust to endure up to the present day; no weight should be attached to this particular example, as any number of other examples would serve equally as well. I could have said, perhaps with greater justification, that we may live in the universe of extremophiles.

[13] Charles Darwin, Journal of researches into the natural history and geology of the countries visited during the voyage of H.M.S. Beagle round the world, under the Command of Capt. Fitz Roy, R.N. 2d edition. London: John Murray, 1845, Chap. XXI (http://darwin-online.org.uk/content/frameset?itemID=F14&viewtype=text&pageseq=1)

[14] Our galaxy may host hundreds or thousands of civilizations at a stage of pre-electrification, prior to any possibility of technological communication or travel, and therefore beyond the possibility of observation until we can send a probe or visit ourselves. But keep in mind that a thousand civilizations unable to communicate by technological means, and distributed throughout the disk of the Milky Way, may as well be so many needles in a haystack.

[14] is interesting because we could have many different planetary civilizations which follow the same technological and psychological evolution of history as ours such as the bronze age, the iron age, the middle ages, etc.

They all will at some point become industrial and then electrical. Consequently we will be able to communicate with them with radio signals in the future. If we send a signal now to one in the middle ages, and if it is five hundred light years away by the time it reaches them, they might have the technology to hear it.

I think you could answer almost all your questions by referring to the conditions on Earth.

Posit being stranded on a remote island. Would that fact that it was a bare volcanic outcrop with just bacteria on it make you feel alone or not. I would go with ALONE.

Suppose the island was a covered in jungle with abundant vertebrate life. Again, I think ALONE would be the reply for all but a few people.

What if the island was inhabited by a primates, even (improbably) a colony of Bonobos. Again ALONE.

What about a stone age tribe. Now we get to a point where with some effort, we can imagine ourselves no longer completely alone. There is the possibility of communication, sharing ideas and belonging to the group. I think we reach a boundary here of NOT-ALONE.

What is instead you meet some fellow stranded people who speak your own language and share your customs. Definitely peers and NOT ALONE.

What if you found evidence that the island was once populated, but no longer, yet the artifacts contain writings that you can decipher? Communication is one way, from the past to the present. I think most people would agree that they are still ALONE.

Similarly, what if you found a working tv that was broadcasting? Would you feel coalone or not. For me that one way communication would still leave me feeling alone.

Finally, you are alone on the island, but you can believe in a God? For some people, they are no longer alone, others they are ALONE.

I suggest that the criteria for being alone or not is whether we can communicate with another entity such that we can share thoughts, even if that communication is a bit erratic.

Timothy Ferris did a PBS show in 1999(?), life beyond earth(?) in it is a pine tree with sparkling lights going on and off.it is a temporal metaphor of our galaxy and each light and how long it blinks on and off is one technological civilization that is born and dies.

if the lights turn on and off fast over time its unlikely that ant two will be lite up at the same time…………………………………………….

A stimulating precis of what we think we know. It’s a wry thought that a sub-light interstellar trip of say 1,000 years or so could be undertaken whereby at inception the target civilisation is at the agrarian stage, and upon arrival may have progressed over the trip time into a full-blown technical civilisation with space travel and whatever lies beyond. It is also the case that, barring tech collapse scenarios, the statistics of the post-industrial future are extremely skewed with respect to those of all of pre-industrial history. Imagine that diagram with an extra billion years tacked on into the future, and those vanishingly small numbers for humans start to bulk up in the big picture. And so it really isn’t fair to exclude the future in our statistics. Indeed, the ‘L’ term in the Drake equation attempts just that by addressing duration.

There’s also that pesky lightcone, which excludes a huge number of potential contact events, assuming all endeavours of detection and travel be sub-light. I have not seen a quantification of this effect but would like to see this discussed in a mathematical fashion.

In any event, your message is well-taken; we have to stand up and move out.

Needle in the Cosmic Haystack: Formal and Empirical Approaches to Life in the Universe… Nick Nielson…

A great post…

Perhaps human civilization, Cain and Able, burned by endless discord, rage, and murder will soon realize a stronger truth…not all intelligence among the stars will be as terrifying as the naked apes of earth…But we are the only standard by which we must judge…ourselves…it is pitiful to realize that on earth life preys on life…the future must be different…it is not an option…

“life, intelligence and civilization are not random”

Well, we really don’t know. It is possible (say) that the appearance of simple life is predictable from the laws of physics and chemistry (e.g. very likely on rocky wet planets). Intelligence on the other hand is a product of the vagaries of evolution and may be highly unlikely to re-occur elsewhere.

Or, it could be that the initial appearance of life is the highly unlikely event but once it occurs intelligence eventually follows, because of some law of evolution that we haven’t discovered yet.

It will require investigation of many worlds before we have the answers.

And there are some who argue that humans would be better off without civilization.

We might as well proceed as though we were the vanguard of life and sentience, which we effectively are.

All these speculations are based on two asumptions who could just as well be wrong : 1. life exists elsewhere in the universe , and 2 . industrial civilisations have a limited lifespan .

If industrial civilisations existst and have existed for billions of years , common sense implies that they would be easily detected , either by sheer number or by the gigantic projects they would need to go on growing , which is the way of all life .

So , if asumption 2. is wrong , it points in the direction of nr. 1 being wrong as well : for every day going by without detection of either lifechemistry on an exoplanet or signal detection from an industrial civilisation , it becomes more probable that we ARE alone in the full sense of the word . If and when this realisation grows strong enough to be accepted by a common sense aproach , our filosofic worldwiev will have to change again : we will again be the center of creation as before Galileo .

Some of us will then feel a responsibility to spread life to other starsystems in a big way , without too many moralistic limitations .

“a thousand civilizations unable to communicate by technological means, and distributed throughout the disk of the Milky Way, may as well be so many needles in a haystack.”

The fact of this notion makes me heartsick.

@Micheal Spencer

If there is a multiverse with an infinite number of different civilizations that are not contactable, is it equally heartsickening?

That civilizations may only extremely rarely, if ever, contact each other is both good and bad, depending on your viewpoint. It does mean that there will be living worlds with possibly treasure troves of information to study. Human civilization[s] will be able to expand without fear of “outsiders” and flower in any number of different ways, with evolution creating many post-human forms.

For folks like Heath Rezabek who want to build vessels to contain all knowledge, the aim should be to include ways to communicate with alien species, as they may be the principal readers. Dead worlds or moons would be ideal places to put those vessels. And those vessels need not be on home worlds, but planted like gifts near worlds that have life and the possibility of an[other] technological civilization emerging. Perhaps that is also a way to get young civs to join a galactic club, by giving them a technological lift that helps synchronize them in some way, facilitating this.

In Clarke’s Odyssey, the intelligence “uplift” that the star faring race was providing may have had that consequence.

Another possibility, suggested by Douglas Adams in THHGTTG, is that civilization go into hibernation and are revived when conditions are right, like the planet builders on Magrathea. This upsets the Drake Equation by allowing L to be shifted in time when it starts and stops, with stasis for long periods.

We’ve only had the ability to communicated with radio long distance for one hundred years which does not take us very far in the galaxy. It seems to me the longer the time goes by the greater the change we will receive a signal.

Our technology becomes more advanced through time. The space age is only 57 years old. I think once a civilization reaches a certain level of advancement, it becomes unstoppable. Most of the lights on that tree are still on! I think that same is true about our civilization. We will survive and get interstellar travel and until we’ve searched every Earth like planet in the galaxy, the fat lady won’t sing.

@ DCM “We might as well proceed as though we were the vanguard of life and sentience, which we effectively are.”

Effectively, yes, and I believe that this effective isolation conveys a moral obligation to preserve and to expand the life, consciousness, technology, and civilization that we only know to be here. If we aren’t alone, we haven’t lost anything by proceeding as though we were the vanguard of life and sentience.

@ Michael Spencer “The fact of this notion makes me heartsick.”

Take heart, I say. I think that the feeling of heartsickness comes from the idea of a loneliness bridgeable in theory but almost unreachable in thought. But if we had the practical means to assuage this loneliness, that would be different, wouldn’t it? The next few hundred years of technological advance may give us this capacity sooner than we suppose, if we do not stagnate. And once we have the capacity, locating other civilizations, if they exist, will also be facilitated by these improved technologies. Whether or not we find a peer civilization, the quest to do so will give meaning to our technological civilization, which has done away with some many of the meanings of traditional civilization. This will be, I think, the mythic quest of industrial-technological civilization.

@ James D. Stilwell “Perhaps human civilization, Cain and Able, burned by endless discord, rage, and murder will soon realize a stronger truth…not all intelligence among the stars will be as terrifying as the naked apes of earth…But we are the only standard by which we must judge…ourselves…it is pitiful to realize that on earth life preys on life…the future must be different…it is not an option…”

Are you familiar with Peter Ward’s Medea hypothesis? This is exactly the idea that, “on earth, life preys on life.” (As a side note, Joseph Campbell emphasized this as a Schopenhauerian insight.) This is an invariant property of life on Earth much older than Homo sapiens. The question is, will be unprecedented emergence of conscious intelligence allow us to outrun this trend and establish redundancy off the planet before we are extinguished by the next mass extinction event.

@ Geoffrey Hillend “They all will at some point become industrial and then electrical. Consequently we will be able to communicate with them with radio signals in the future.”

I think it would be better to say that some percentage of them will industrialize and produce an electrical technology.

You have made, in brief, the argument for METI (messaging extraterrestrial intelligence). This is controversial and widely discussed. Cf. my earlier Centauri Dreams post “SETI, METI, and Existential Risk” (https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=29474).

@ steven rappolee “Timothy Ferris did a PBS show in 1999, Life Beyond Earth. In it is a pine tree with sparkling lights going on and off.it is a temporal metaphor of our galaxy and each light and how long it blinks on and off is one technological civilization that is born and dies.”

I have this Timothy Ferris program on DVD and have watched it several times. The tree with lights is a powerful metaphor. Carl Sagan also made this point several times, and in the classic formulation of the Drake equation the longevity of technological civilization is the last term of the equation.

Because of the anxiety over our potential longevity, the study of existential risk has taken on a particular urgency. As noted in the essay above, our history gives us data points for the past, if life on Earth is representative, but no data points for the future, so our speculation on million and billion year old civilizations in the universe is unmoored at present. This is also noted in the comment above by Andrew Palfreyman, who noted:

“Imagine that diagram with an extra billion years tacked on into the future, and those vanishingly small numbers for humans start to bulk up in the big picture. And so it really isn’t fair to exclude the future in our statistics.”

I agree with this, but we lack a sufficiently robust intellectual infrastructure for thinking about the future in scientific terms. Only in our time has a truly scientific historiography become possible through technological means of studying the past. Our historical consciousness that seeks to make sense of this expanded and extended history still lags behind. Part of this historical consciousness is the understanding of the human place in time. I hope to do further work on this, as it is a central question of my current research.

Phew! Great Post; so much stimulation and information to absorb I shall be head encased for some time.

However; what if – as Frank Tipler has speculated; Life, the Universe and what’s for dinner is the product of a computer programme?

Just a thought!

Alex writes: “If there is a multiverse with an infinite number of different civilizations that are not contactable, is it equally heart sickening?”

Yes. Recently I finished Krauss’ “A Universe From Nothing”, in which he infinite universes. More interestingly he describes a view of our own universe replete with regions impossible to ever image. In this view, our place in this universe is small indeed.

Heartsick, yes. And lonely. Indeed all that matters is what one makes of one’s life. The question of exactly where will remain unresolved. There is nothing to give life value other than what you make of it.

Nick writes: “Take heart, I say.”

Indeed, Nick; I’m forever mindful of my parochial views. Or rather the parochial views of the world and place I find my self living.

But ponder this: how would you explain to the cat sitting on my desk right now that I prefer, say, a Mac over a PC? This is perhaps the bridge we need to cross and I’m not convinced that humans as we stand now in time are capable of more in this universe than scratching ourselves.

We will need something far more than the technology presently imaginable.

I suggest that any technological civilisation will, in due course, produce nuclear weapons. It further seems to me that it may well be inevitable that, in the course of time, these civilisations will destroy themselves using these weapons. (I am suggesting that aggression is an inevitable part of technological know-how). This is my explanation of the Fermi paradox. Am I making too many assumptions? I invite comments.

you have a spelling error in your “cone” diagram. Disappointing. I’m a very good proof reader and I’m looking for a job.

@Alex Tolley – Agreed: Casting our knowledge and traces into forms that might be recovered, and allow a bootstrapping from simpler to the more complex technologies, would be the ideal.

Conveniently, such a vessel archive would serve its purpose whether the aliens were distant from us in space and time, or only in time: in other words, if the aliens were ourselves, rediscovering those traces after a long lapse of capability.

I like your idea of such stepping stones as a gift; if the recipients were ourselves after a lapse, then the result would be Adams’ hibernation scenario (we would re-awaken from cultural slumber). If those from other worlds, then the result might be uplift as per Clarke.

In the tale of Gilgamesh, he becomes heartsick over the loss of Enkidu, his friend. This sends him on a quest to achieve eternal life. Though he ultimately finds this impossible for himself, the tale of his quest as contained in the vessel of his name has achieved it. Imagine if this tale were to be passed on to distant civilizations — whether descended from ours or descended from another world’s.

Gilgamesh ought be heartsick no more.

Megis : the short answer is that yes , you are making too many asumptions.

For some reason nobody here wants to relate to the very real posiblity that we realy are alone . this might not sound very interrresting , but might actually have far ranging positive results .

Also we have no reason to believe nuclear wars would have to be the end of a civilisation . Building on facts , as oposed to pseudoreligious ideology , it seems that a very small one-time-only nuclear war in 1945 was more than enough to make mankind almost hysterically carefull and afraid of anything nuclear . This effect has so far lasted without weakening for 70 years , and extrapolating into the future from here , it is more realistic to expect that any probable future nuclear war will be very limited from a global pespektive , and that it will have a proportionaly bigger preventive efect , perhabs leading to forced disarmament of the guilty beligerents by the more responsible behaving international powers .

Nick Nielson writes…

“on earth, life preys on life.” (As a side note, Joseph Campbell emphasized this as a Schopenhauerian insight.) This is an invariant property of life on Earth much older than Homo sapiens. The question is, will be unprecedented emergence of conscious intelligence allow us to outrun this trend and establish redundancy off the planet before we are extinguished by the next mass extinction event.

I fear that in the total scheme of things every action comes with an equal and opposite reaction…Death will surely beget death…clinging to life by extinguishing another life to prolong our own dooms humanity to final obliteration…there will be no mercy shown to the merciless and this is the highest law…above and far beyond the grandest human philosophy…

Think twice about the wisdom of men rationalizing their ages of slavery and savagery…

@ Bob Andrews

Funny you should mention that, as I am hoping (assuming I can finish it) that my next Centauri Dreams post will involve the simulation hypothesis.

In any case, I’m very pleased you found my post stimulating.

@ megis

Carl Sagan especially emphasized the possibility of the destruction of civilization by nuclear warfare, and he even described a dream he had about this (and I wrote about this dream in the following: http://geopolicraticus.wordpress.com/2012/12/10/carl-sagans-dream/). Since the end of the Cold War (during which Sagan did most of his work), risk of MAD-style nuclear war is widely believed to have decreased, and so studies of existential risk tend to focus on other threats to civilization, though, to be sure, nuclear weapons remain a danger. But I will go farther than that. I think that the weapons we may develop in the next 100-200 years will make nuclear bombs look like firecrackers. Matter-antimatter reactions would be a wonderful form of power for starships, but the mastery of this technology would also mean matter-antimatter weapons.

What is the spelling error? I try to catch them, but if you mean my reference to “esocivilization” (not in the text) please cf. my post “Eo-, Eso-, Exo-, Astro-” http://geopolicraticus.wordpress.com/2012/09/11/eo-eso-exo-astro/

@ Michael Spencer

Thanks for your comments. Most recently you wrote: “But ponder this: how would you explain to the cat sitting on my desk right now that I prefer, say, a Mac over a PC? This is perhaps the bridge we need to cross and I’m not convinced that humans as we stand now in time are capable of more in this universe than scratching ourselves. We will need something far more than the technology presently imaginable.”

I’m not sure that I follow you. Do you mean to say that our relationship to the wider universe involves an epistemic disconnect on the order of your relationship to your cat? If so, I agree, but we are learning, and, perhaps more importantly, we have learned how to learn scientifically. This is a big change. If you meant something else, please elaborate.

Our “scratching ourselves” is slowly but surely becoming more effective. Think of it this way: the same technologies upon which we are now working that will give us transhumanism will also give as trans-speciesism, i.e., not only human beings, but other species will also have the opportunity to transcend the biology bequeathed to them by nature. This may happen even before interstellar flight. If so, you might easily explain to your cognitively enhanced cat why you prefer MAC OS over PC OS, and your cat may well answer you back with a different opinion.

In other words, we are on track not only to increase our knowledge, but also to increase our ability to learn, and this may well take us beyond “technology presently imaginable.”

“on Earth, life preys on life”

Perhaps one of the “necessary evils” that has enabled our existence. It’s been suggested that in the absence of predation, life would have got stuck at the level of unicellular autotrophs. Predation may have been a driver of evolutionary experiments such as multicellularity which ultimately led to you and me.

If true, it would mean that predation, along with other essential factors such as plate tectonics (which also produces earthquakes), large-scale atmospheric circulation (which also causes hurricanes), and the sheer fecundity of evolution (which produced AIDS and guinea worm by the same processes that produced humans) are the price we pay for existing at all.

@ James D. Stilwell

I haven’t made any attempt to rationalize human evils. Far from even suggesting that we should be, “clinging to life by extinguishing another life to prolong our own,” I have suggested in several contexts that humanity’s connection to all other forms of life, and to the biosphere on the whole, is central to our interstellar future. For example, this was a theme of my Centauri Dreams post “Extraterrestrial Dispersal Vectors” (https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=30024) .

More recently I wrote, “…the most significant role that human beings may play in cosmic history is that of employing our industrial-technological civilization as a dispersal vector for Earth-originating life to expand into the cosmos at large. In this case, we may be better known in the future through non-human species than for our own species, and we would do well to remember that in our dealings with other species and with the biosphere on the whole.” (http://geopolicraticus.tumblr.com/post/89311474207/lori-marino-leader-of-a-revolution-in-how-we-perceive)

You also wrote, “…there will be no mercy shown to the merciless.” I agree with this. I would also say that there will be no mercy shown to the merciful either. The universe is indifferent to us. As Pascal said: “…even if the universe were to crush him, man would still be nobler than his slayer, because he knows that he is dying and the advantage the universe has over him. The universe knows none of this.”

In a similar vein, though coming from a very different perspective, Richard Dawkins wrote, “The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.” (the last chapter of River Out of Eden)

All civilizations are vulnerable to permanent collapse, at least until

they arrive at an advanced space age. It is possible that 99% of

all civilisation making their way through a Stone Age period will not

exit it. On earth it lasted more than 3 million years. In that time

we know of atleast of a few events that pushed these proto-humans to

the edge of extinction.

Obcourse what we don’t know is if the ordered state of our solar system

is a six-sigma event. The Kepler mission could not tell us that, as it was

not desgined for this task. There are niggling possilities that maybe waiting

for us. For example, What if Terrestrial twins of Earth only occur in conjunction with Suns with in 2% of our sun’s mass. Are crusts in twin earth

doomed to melt and reform evey few hundred million years because their mantles are too thick and never had the “theia” event, there are probably are many more of these critical pathways that we just don’t have enough data on.

So yes, darned fortunate luck cannot be eliminated as the

answer to the Fermi question.

Nick Nielsen said on July 27, 2014 at 18:44

“I think that the weapons we may develop in the next 100-200 years will make nuclear bombs look like firecrackers. Matter-antimatter reactions would be a wonderful form of power for starships, but the mastery of this technology would also mean matter-antimatter weapons.”

That is probably an accurate prediction, and I believe it ties into some comments made in the previous CD topic about ethics and motivation involved in ETI interactions, directly mirroring contemporaneous Terran ones. Mutually assured destruction is definitely a reality on Earth, but an advanced non-terran civilization (assuming they can be affected by our means of warfare) could use such an observation as leverage against us, for us (to dominate/scare them), or with us (as a moral equalizer). Perhaps, as the article of my https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=31157#comment-120267 hypothesizes: intelligence, technology and ethics co-evolve as required necessities to ensure that order between species or even natural phenomena stay in tact, especially as species begin to acquire better and more intuitive ways of manipulating or disrupting it to fit their growing desires and behavioral needs.

Imaginably, this may take an interesting twist if super-hunters or hyper-warrior lifeforms exist, choosing to make contact with other species when and only they reach a certain level of tactical prowess or combatant intrigue. A humanistic parallel would be like sizing up your target as a “worthy opponent” or some such other creative euphemism. I don’t know about you, but I doubt it’d be treats we’d receive during a Predator Halloween. :)

@Nick:

Yes, you have my meaning exactly, but I am not sure that I share the idea that we will eventually figure things out.

As Krauss explained the multiverse concept I found myself drained emotionally, drowning in my own inability to conceive of a time when these vast distances might be bridged. On the other hand, as I thought more through the day yesterday about my cat and my computer, I wondered about, say, a Sumerian and an iPhone. It’s heartening.

And I don’t know why the unreachable nature of the universe is so evocative.

The point in the main article that the pattern of evolution of life on earth offers important insight into this question is a very good one I think. In this comment I am assuming DNA based life on earth like planets.

If we take as a given that life begins (or appears) on a planet small and simple and that mutations HGT etc. lead to what could be modelled as a random walk through gene space we end up with some interesting statistical patterns.

As the origin (or appearance) or life on earth was at or close to the lower limit for complexity the result of random variations over time is to increase the variance in any one specific characteristic (e.g. size) across the biosphere as a whole. Many lineages stay simple, or perhaps regress, but over time the most genetically complex organism present in the biosphere (or the one with the highest value of any particular variable such as mass, intelligence etc.) will tend to following a rising trend (no doubt with short term fluctuations due to extinctions and speciation events).

I am further making an assumption that the underlying causes of these variations are entirely natural and derive ultimately from physics. The precise patterns will no doubt vary with local geology, climate, random events such as major impacts etc. but there may be an underlying pattern of increasing variance in specific characteristics over time, until upper limits of the available gene space are approached (in terms of what can survive in specific environments – which will again vary spatially and temporally).

Sharov has published papers on this apparent pattern – which he finds to be log linear. I have some issues with his overall interpretation of the data (despite being favourably inclined towards the panspermia hypothesis), but the basic pattern strikes me as entirely predictable on statistical grounds.

We know (as we exist) that the probability of intelligent life emerging on an earth like planet in 4by is >0. The above pattern suggests it may require something close to that to be achieved (with great uncertainty around that point) but with terrestrial planets by the billion around for 10by we seem to be pushing the ‘we are alone’ option into a very finely tuned narrow range of probabilities only fractionally above 0. In practice the numbers that come out of almost any probability value you care to plug into the equation very rapidly move beyond the numbers where one could comfortably conclude that all such civilisations destroyed themselves or were killed off eons ago. Perhaps I am an optimist on this, but I take the probability that we ourselves will make it to the point where we can travel interstellar distances is >0

The data seems to ‘hollow out’ the range of credible options regarding this basic question.

a) We have made a fundamental error in one of our assumptions and life is an incredibly unlikely fluke here on earth. But what assumption is wrong?

b) Some civilisations will have achieved interstellar travel over the last 6 billion years or so, making them largely immune to extinction. Their technology may well not be recognisable. For this to be true they would have to choose not to interfere with life elsewhere to any noticeable extent to account for the ‘great silence’. As we are talking about billions of years this would have to include not interacting to a noticeable extent with any life up to our current stage of development.

c) The range in between – small numbers of scattered civilisations out of contact is so incredibly fine tuned in terms of the probabilities that I view it with suspicion.

“9. Hominids split off from other primates somewhere in the neighbourhood of five to seven million years ago…about half of a thousandth of one percent of the age of the universe.”

More like half of a thousandth of the age of the universe.

Your Light Cone has the Esocivilisation Observer as a point but if the civilisation spreads out in space and/or time the amount of hypersurface of the present accessible increases to an area. The Light Cone becomes more like a Unit Hyperbola rotated around the time axis.

Did Hominids advance in technology during previous interglacial? I bet they did only to revert by some extent during the glacial periods. I am sure we’ll stay reasonably advanced during the next glacial period but you can’t extrapolate an exponential advance forever without pull backs.

Finding peer civilisations will not be the reason humanity expands into the galaxy. Defending against them would be a good reason though. There’s plenty of resources in our solar system in the mean time.

http://arxiv.org/abs/1407.4895

Nightfall: Can Kalgash Exist

Smaran Deshmukh, Jayant Murthy

(Submitted on 18 Jul 2014)

We investigate the imaginary world of Kalgash, a planetary system based on the novel “Nightfall” (Asimov & Silverberg, 1991). The system consists of a planet, a moon and an astonishing six suns. The six stars cause the wider universe to be invisible to the inhabitants of the planet. The author explores the consequences of an eclipse and the resulting darkness which the Kalgash people experience for the first time. Our task is to verify if this system is feasible, from the duration of the eclipse, the “invisibility” of the universe to the complex orbital dynamics.

Comments: 8 pages

Subjects: Popular Physics (physics.pop-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:1407.4895 [physics.pop-ph]

(or arXiv:1407.4895v1 [physics.pop-ph] for this version)

Submission history

From: Jayant Murthy [view email]

[v1] Fri, 18 Jul 2014 06:40:55 GMT (864kb)

http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1407/1407.4895.pdf

@ NS “It is possible (say) that the appearance of simple life is predictable from the laws of physics and chemistry (e.g. very likely on rocky wet planets). Intelligence on the other hand is a product of the vagaries of evolution and may be highly unlikely to re-occur elsewhere. Or, it could be that the initial appearance of life is the highly unlikely event but once it occurs intelligence eventually follows, because of some law of evolution that we haven’t discovered yet.”

A distinction needs to be made between randomness in origin and randomness in development. When I said that the universe, life, and intelligence are not random, I meant that they are not random in their development, though randomness may play a role in their origins. The mutations upon which natural selection works are random — we could readily calculate a standard deviation for mutations in DNA — but the selection itself it not random. Once intelligence gets started, its origins may have an element of randomness, but its development clearly shows trends and patterns.

“And there are some who argue that humans would be better off without civilization.”

I explicitly addressed exactly this question in my talk at the first 100YSS symposium in 2011, “The Moral Imperative of Human Spaceflight.” In this I attempted to make an explicit argument for the value of civilization. (A similar argument appears in the appendix to my book Political Economy of Globalization). If you’d like to read my paper I would gladly send you a copy.

@ Ole Burde

I was pretty careful to formulate all my remarks on the existence and longevity of life and civilization in probabilistic or hypothetical terms, so I would not give the impression that I was assuming that there is other life in the universe. If this was not clear, allow me to be explicit: I do not assume that there is other life in the universe. All that I wrote above is consistent with the rest of the universe being sterile, and ourselves the sole oasis of life. In fact, the possible uniqueness of terrestrial life is a point I have used in several arguments concerning our need to protect and secure the only life that we know of in the universe.

“… it becomes more probable that we ARE alone in the full sense of the word. If and when this realisation grows strong enough to be accepted by a common sense approach, our filosofic worldview will have to change again…”

An increasing number of philosophers today are considering just this question and asking how to reconcile the possible isolation of humanity and terrestrial life with the Copernican principle and its corollaries. It is an interesting question upon which I have spilled a great deal of ink, and I hope to continue working on it until I have arrived at a definitive formulation. But the evidence is not yet in, so an enormous amount of science must needs go hand-in-hand with philosophy on this question.

@ roger “Your Light Cone has the Esocivilisation Observer as a point but if the civilisation spreads out in space and/or time the amount of hypersurface of the present accessible increases to an area. The Light Cone becomes more like a Unit Hyperbola rotated around the time axis.”

I lack a grasp of relativity theory sufficient to give a mathematical expression to my theory of civilization, but what you express is pretty much what I had in mind in my post Stepping Stones Across the Cosmos. Needless to say, I would be very pleased indeed if someone with a background in relativity who also understood the point I was trying to make in Stepping Stones Across the Cosmos were to give mathematical expression to my formulations.

“Did Hominids advance in technology during previous interglacial? I bet they did only to revert by some extent during the glacial periods. I am sure we’ll stay reasonably advanced during the next glacial period but you can’t extrapolate an exponential advance forever without pull backs.”

I agree that one can’t extrapolate an advance without pull backs, but two steps forward and one step back will still move us forward in the long run. And we have advanced considerably in the millions of years of hominid evolution.”

“Finding peer civilisations will not be the reason humanity expands into the galaxy. Defending against them would be a good reason though.”

I suggest that future civilization, if it becomes spacefaring, will be sufficiently pluralistic that more than one motive will be a driver in our expansion through the cosmos. For me, finding a peer civilization would be a high priority, but I would not be disappointed if I did not find one. The effort to find a peer civilization will likely uncover many other things that are of interest, and in the very long term our diaspora will be the source of a diversity of life and civilization in the universe, as the adaptive radiation of terrestrial life in the cosmos assumes many different forms. In time, we will be the aliens that we find.

Nick, I would like a copy of your talk at the first 100YSS symposium in 2011, “The Moral Imperative of Human Spaceflight.” Would you email it to me? landahl1@mac.com. Thank you very much.

Erik Landahl

NASA readies yet another mission to Mars to search for evidence of past life:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=65218

Because searching for any present living life there is risky and terrible if one fails, apparently. We may have been less knowledgeable in the days of Viking and before, but we were certainly more confident and bolder. And the masses seem to miss the point that a negative finding is just as important for scientific knowledge as a positive one.

Hmmm, maybe NASA is getting a bit bolder/smarter after almost 40 years:

NASA Still Won’t Look For Existing Life on Mars (Update)

By Keith Cowing on July 31, 2014 3:10 PM

http://nasawatch.com/archives/2014/07/nasa-still-wont.html

To quote from the above article:

Keith’s update: I asked the following question at the Mars 2020 Rover press event today. “Your press release says “determine the potential habitability of the environment, and directly search for signs of ancient Martian life.” Why isn’t NASA directly searching for signs of EXISTING LIFE on Mars? And I will ask my follow-up since the answer to this question is always “we don’t know how to look for life on Mars – yet”. – How are you going about the task of learning how to look for existing life on Mars, when will you have this capability and why is it that NASA was eager to search for existing life on Mars 40 years ago but is unwilling or unable to do so now?”

I obviously expected Jim Green to answer in the same cautious way that NASA has always answered this question – one I have asked again and again for the nearly 20 years. Instead, Green launched into a detailed description of all the things that the Mars 2020 rover could detect that have a connection with life. Much of what he said clearly referred to extant / existing life. Now THAT is cool. To clarify things I sent the following request to NASA PAO “Can the Mars 2020 rover detect extant/existing life on Mars? Will NASA be looking for extant/existing life on Mars?” Let’s see how they respond.

There is also a link to a brief paper in the article’s comments section on some developing new life detection technology that looks very interesting. See here:

http://www.lpi.usra.edu/meetings/marsconcepts2012/pdf/4065.pdf

I will go this far: If there are living organisms on Mars right now, then that means they have somehow survived some rather seriously harsh conditions for ages. This implies not only hiding deep below the surface in some warm little pool of water, for example, but hardier types that live near or even on the surface. Immune to ultraviolet radiation and transient liquid water. We know of such creatures on Earth, so why not Mars?

As Monty Python would say, it’s not quite dead yet and we have barely begun to seriously explore the planet in detail. A few orbiters and rovers do not a final answer make for a whole planet.

The simplest explanation must be prefared when everything else is equal ., so says one of the most basic priciples of organized thought .

If life existed elsewhere in a large number of places ,you would expect some of them to have survived to a stage where they would easily fill up the whole galaxy . That is what life does , given enough time and oportunity .

The simplest explantion for the fact that intelligent life is not obviously detectable everywhere we look , is therefore that we are alone , at least in this galaxy . Ofcourse there could be any number other explanations , but as for now our working hypotesis should be the simplest one .

@ ljk

It’s not just that there is a risk of failure in searching for contemporary life on Mars, NASA is also risk-averse when it comes to public relations, and for good reason, because they get their budget from taxpayers. Thus anything that sounds even mildly “out there” (like searching for life on Mars) gets downplayed or paraphrased so they don’t get beaten over the head by some outraged congressperson.

The same thing happens at NSF, which does not allow “evolution” to appear in the title of any research project, because they know the American public will howl if taxpayer monies are used to fund anything explicitly evolutionary, but all biology today is evolutionary, so it is simply necessary to paraphrase.

@ Joëlle B.

Thank you so much for making me aware of your Centauri Dreams post. I will study it carefully. This offers a really unique perspective on the Fermi paradox, as well all hypotheses among the class of responses to Fermi that assume that ETI is waiting to contact us until we are “ready” or “worthy.” Usually this worthiness to enter into interstellar and intergalactic society is framed in glittering generalities, but I have to admit I hadn’t thought about ETI waiting to contact us until we can put up enough of a fight to be interesting.

If we take a naturalistic view of the evolution of ethics (as, for example, in Frans de Waal and Soshichi Uchii), then the coevolution of intelligence, technology, and ethics that you mention means that ethics changes in essence when its coevolutionary cohort changes. In so far as the advent of industrial-technological civilization involves the exponential growth of technology, this growth in technology will be a significant driver in the evolution of the moral life of humanity. I am in complete agreement with this, and I would like to see a definitive formulation of this idea.

Best wishes,

Nick

Nick Nielsen said on August 6, 2014 at 3:42:

“It’s not just that there is a risk of failure in searching for contemporary life on Mars, NASA is also risk-averse when it comes to public relations, and for good reason, because they get their budget from taxpayers. Thus anything that sounds even mildly “out there” (like searching for life on Mars) gets downplayed or paraphrased so they don’t get beaten over the head by some outraged congressperson.”

Funny how NASA and various aerospace corporations were not afraid of a few little bugs on Mars in the first few decades of the Space Age. Certainly in those days there were plenty of other areas of thought that were close-minded if not barbaric in regards to “out there” ideas, yet our space agency considered it a logical duty to search for life on the Red Planet.

For example, one early 1960s plan for a manned Mars mission not only assumed life was there but that the astronauts would be instructed to see if they could use them as a food source to supplement the supplies they brought with them!

It would seem we are not only becoming a risk-adverse society but an imagination-adverse one as well. NASA needs to take some risks when it comes to selling space – and you think it would be a subject that could practically sell itself. Showing long minutes of people sitting at consoles in Mission Control as they often do on NASA Television – boring an audience into disinterest is no less risky?

Curiosity Rover Celebrates Second Anniversary on Mars as it Approaches Mountain Goal

By Paul Scott Anderson

The Curiosity rover has been actively exploring Mars for two years now, and as it celebrated its second anniversary today, August 5, it is also, after a lengthy journey, approaching its primary mission goal – the massive Mount Sharp in the middle of Gale crater.

Curiosity first landed on Mars on August 5, 2012, PDT (August 6, 2012, EDT), and has already immensely expanded our knowledge of the Red Planet, in particular of course its landing site in Gale crater. The roving laboratory has confirmed the previous existence of ancient riverbeds and a lakebed which used to fill portions of Gale crater billions of years ago.

While not directly looking for signs of ancient life, Curiosity has been studying the rocks and terrain for evidence of a previously habitable environment, the primary goal of the mission. According to scientists involved, it has already done that, in spades, and it didn’t even have to travel very far.

“Before landing, we expected that we would need to drive much farther before answering that habitability question,” said Curiosity Project Scientist John Grotzinger of the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena. “We were able to take advantage of landing very close to an ancient streambed and lake. Now we want to learn more about how environmental conditions on Mars evolved, and we know where to go to do that.”

Full article here:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=65471

To quote:

As a nuclear-powered rover not dependant on solar panels like Spirit and Opportunity, it is expected that Curiosity will be able to continue to explore this fascinating place on Mars for at least several more years, barring any tragic accidents or the like of course. The scenery in the foothills of Mount Sharp should be like none seen before in Mars exploration history.

The Automated Biological Laboratory

By Andrew Lepage

August 7, 2014

Last week NASA announced the list of instruments that have been selected for their upcoming Mars 2020 Rover mission. Along with the pair of rovers still active on the Martian surface (including Opportunity which has been on the move for over a decade now), the Mars 2020 Rover mission will continue the exploration of the Martian surface whose history stretches back to the Viking program which successfully placed a pair of landers on the surface 38 years ago.

While these Martian explorers are well known to most space enthusiasts today, their success is due in part to development work performed by NASA and its contractors a half a century or more ago. Among these earliest development programs was a little-known Mars lander concept known as the Automatic Biological Laboratory or simply ABL.

Full article here:

http://www.drewexmachina.com/2014/08/07/the-automated-biological-laboratory/

“For example, one early 1960s plan for a manned Mars mission not only assumed life was there but that the astronauts would be instructed to see if they could use them as a food source to supplement the supplies they brought with them!”

“I hadn’t thought about ETI waiting to contact us until we can put up enough of a fight to be interesting.”

I’ve been watching and re-watching Star Trek episodes (since I wasn’t born yet when most of it was on TV and too young to know what was going on when it was [luckily the CBS website has nearly every episode of each series for free), and came across this particular episode that touches on these issues: http://www.cbs.com/shows/enterprise/video/1477086260/enterprise-rogue-planet/

[SPOILERS BELOW]

TV Critics don’t seem to like this episode, but from a scientific stand-point I think it’s brilliant. The crew meets a species of hunters, called the Eska (who have been as such for millenia) on a rogue planet with thermal vents enabling oases for habitability on the surface. The Eska have been traveling to this planet (Dakala) for nine generations (which, depending on life span could be a great deal of time), hunting the native species (save for higher primates [which hints to their own ethics and evolutionary history]).

http://en.memory-alpha.org/wiki/Eska

http://en.memory-alpha.org/wiki/Dakala

In contrast, at this point in human/vulcan history, it is seen as unethical to hunt (and even to eat meat in the case of observant Vulcans).

By the end of the episode (and throughout much of the Enterprise series) you begin to understand that even though the crew means well (or so they think), they are highly bigoted in regards to other sentient species. Even though the ETI native to Dakala reached out to Captain Archer to protect them from the Eska, by heeding their request he directly interrupted both the Eska’s and Wraith’s evolutionary paths by disrupting the balance of power between the two species.

The Eska earned by their own intelligence the capabilities to detect the Wraiths, yet Captain Archer deceptively disrespected this process. If the Wraith hadn’t appeared as the woman of Archer’s fantasies would he still have been as motivated to throw the Eska under the bus as T’Pol initially recognized? And could it not also be seen as a tactic of deception by the Wraith to take such a psychologically powerful form to enhance their competitive edge once the opportunity arose?

One would initially argue that the encouragement of the preservation of life trumps all ethics and morality, but this is not the case in the series, since just a little before (in a previous episode http://www.cbs.com/shows/enterprise/video/1477083541/enterprise-dear-doctor/ ) Archer allowed an entire species to die of a genetic disease, even after a cure was found AND refused to help them develop a space travel capacity that could help them find someone who would help them! The reason?: He didn’t want to ‘play god’. Dear Captain Archer, isn’t that what you just did to the Eska and Wraiths? Oh, what hypocrisy.

The beauty of the episode is that you realize no one in the Star Trek universe is really being helped or hurt, rather that biological warfare is unavoidable, constant and can even be unrecognizable by its participating members if deceptive measures are successfully executed.

I mean, imagine if the Wraiths eliminated the Eska and developed technology… you’d have a super race of shapeshifters, who could not only read your mind, but become what was in your mind! Sounds a lot like the right ingredients that precursored what happened later on in the future which climaxed into the Dominion War of Deep Space 9.

http://en.memory-alpha.org/wiki/Dominion_War

But I guess that would be an example of a species beating all odds and ultimately coming on top to rule the universe. Thus, an advantage to waiting until your target is at a certain level is for your own prospective empowerment–adaption being the trigger.

I know what you are saying in one sense, but how would you feel having the lives of your whole species constantly threatened by another one? Yes you might evolve to outwit and eventually defeat them, but will you learn from this and become a better being? Or will you become the predator on other species?

There is this tradition that hardship makes a person better. Sometimes it does. But those who cannot handle it are often ridiculed and shunned, often leading to their demise. Sometimes you get a better person out of adversity, but you also end up with broken survivors and those who turn into arrogant SOBs who prey on others for a variety of reasons that have squat to do with evolution.

Overcoming obstacles only works for the better if there is a positive goal in sight and a place to learn from the events and have time to improve. Otherwise you end up with creatures who can barely function or function at a base level and in the harshest ways. These types often fail to see past their little worlds and its issues let alone want to venture to the stars. There is a reason why for most of human history only a few places could be considered truly civilized and even they had their gaps of darkness.

Avoiding “Sagan Syndrome.” Why Astronomers and Journalists should pay heed to Biologists about ET.

Monday, November 25, 2013