I don’t envy the track chairs at any conference, particularly conferences that are all about getting large numbers of scientists into the right place at the right time. Herding cats? But the track model makes inherent sense when you’re dealing with widely disparate disciplines. Earlier in the week I mentioned how widely the tracks at the 100 Year Starship Symposium in Houston ranged, and I think that track chairs within each discipline — already connected to many of the speakers — are the best way to move the discussion forward after each paper.

Still, what a job. My friend Eric Davis, shown at right, somehow stays relaxed each year as he handles the Propulsion & Energy track at this conference, though how he manages it escapes me, given problems like three already accepted presentations being withdrawn as the deadline approached, and one simple no-show at the conference itself. Unfortunately, there were no-shows in other tracks as well, though the wild weather the night before the first day’s meetings may have had something to do with it.

Processes will need to be put in place before future symposia to keep this kind of thing from happening. Fortunately, Eric is quick on his feet and managed to keep Propulsion & Energy on course, and I assume other track chairs had their own workarounds. A high point of the conference was the chance to have dinner and a good bottle of Argentinian Malbec with Eric and Jeff Lee (Baylor University), who joined my son Miles and myself in the hotel restaurant.

The Antimatter Conundrum

I found two papers on antimatter within Eric’s track particularly interesting given the challenge of producing antimatter in sufficient quantity to make it viable in a future propulsion system. We’d love to master antimatter because of the numbers. A fusion reaction uses maybe one percent of the total energy locked up inside matter. But if you can annihilate a kilogram of antimatter, you can produce ten billion times the energy of a kilogram of TNT. In nuclear energy terms, the antimatter yields a thousand times more energy than nuclear fission, and 100 times more energy than fusion, a compelling thought for interstellar mission needs.

Sumontro Lal Sinha described the requirements for a small, modular antimatter harvesting satellite that could be launched into the Van Allen radiation belt about 15,000 kilometers up. I was invariably reminded of James Bickford’s ideas on creating an antimatter trap in an equatorial orbit around the Earth that could harvest naturally occurring antiparticles — Bickford has always maintained that space harvesting of antimatter using his ‘magnetic scoop’ is five orders of magnitude more cost effective than producing antimatter on Earth. In any case, antimatter resources here and elsewhere in the Solar System offer useful options.

Remember that the upper atmosphere of the planets is under bombardment from high-energy galactic cosmic rays (GCR), which results in ‘pair production’ as the kinetic energy of the GCR is converted into mass after collision with another particle. Out of this we get an elementary particle and its antiparticle. Planets with strong magnetic fields become antimatter sources because particles interact with both the magnetic field and the atmosphere. Sinha’s harvester would be an attempt at pair-production that he describes as lightweight and modular. I haven’t seen a paper on this one so I can’t go into useful detail. I’ll hope to do that later.

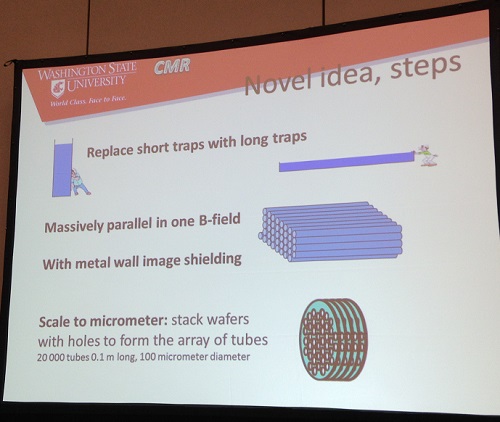

Storing macroscopic amounts of antimatter for propulsion purposes is the other side of the antimatter conundrum, an issue tackled by Marc Weber (Washington State), who described long antimatter traps in the form of stacks of wafers that essentially form an array of tubes. Storage is an extreme issue because like charges repel, so that large numbers of positrons, for example, generate repulsive forces that magnetic bottles cannot fully contain. Weber’s long traps are in proof-of-principle testing as he tries to push storage times up.

Image: One of Marc Weber’s slides, illustrating principles behind a new kind of magnetic storage trap for antimatter.

Thermonuclear Propulsion and the Gravitational Lens

It’s always a pleasure to see old friends at these events, and I was happy to have the chance to share breakfast with Claudio Maccone, whose long-standing quest to see the FOCAL mission built and flown has come to define his career. But in addition to speaking about the gravitational lens at 550 AU and beyond, Claudio was in Houston to discuss the Karhunen-Loève Transform (KLT), developed in the 1940s to improve sensitivity to artificial signals by a large factor, another idea he has long championed. The idea here is that the KLT has SETI applications, helping researchers in the challenging task of sifting through signals that may be spread through a wide range of frequencies.

Consider our own civilization’s use of code division multiplexing. Mason Peck was also talking about this at the conference — the reason you can use your cellphone in a conversation is that multiple access methods (code division multiple access, or CDMA) allows several transmitters to send information simultaneously though using the same communications channel. Spread-spectrum methods are at work — the signal is sent over not one but a range of frequencies — and you’re actually dealing with a combination of many bits that acts like a code. If we’re using these methods, perhaps a signal we receive from an extraterrestrial civilization may be as well, and perhaps the best way to unlock it is to use the KLT.

I missed Claudio’s session on the KLT but was able to be there for his talk on using the gravitational lens as a communications tool. Beyond the propulsion question, one of the biggest problems with putting a probe around another star is data return. How do we get a workable signal back to Earth? Fortunately, the gravitational lens can offer huge gains by employing the focusing power of the Sun on electromagnetic radiation from an object on the other side of it. Using conventional radio communications would require huge antennae and substantial (and massive) resources aboard the probe itself. These would not be necessary if we fly the needed precursor mission to the distances needed to use the gravitational lens.

Thus we send a relay spacecraft not toward Alpha Centauri but in exactly the opposite direction. Ordinary radio links can be easily maintained. If we tried conventional methods using a typical Deep Space Network antenna and a 12-meter antenna aboard the spacecraft (assuming a link frequency in the Ka band, or 32 GHz, a bit rate of 32 kbps, and 40 watts of transmitting power), we still get a 50 percent probability of errors. A relay probe at the gravitational lens, however, shows no bit error rate increase out to fully nine light years.

I’m moving quickly here and I can’t go through each presentation, but I do want to mention as well Friedwardt Winterberg’s talk on thermonuclear propulsion options. Dr. Winterberg has a long history in researching nuclear rocketry, dating back to the days of Ted Taylor, Freeman Dyson, and the era of Project Orion (which he could not join because he was not yet a US citizen). The Atmospheric Test Ban Treaty of 1963 was one of the factors that put Orion to rest, but Fred has been championing nuclear micro-bombs with non-fission triggers, an idea he first broached at a fusion workshop all the way back in 1956. His most recent paper reminds us of von Braun’s ideas about assembling a huge fleet in orbit for the exploration of Mars:

A thermonuclear space lift can follow the same line as it was suggested for Orion-type operation space lift, but without the radioactive fallout in the earth atmosphere. With a hydrogen plasma jet velocity of 30 km/s, it is possible to reach the orbital speed of 8 km/s in just one fusion rocket stage, instead of several hundred multi-stage chemical rockets, to assemble in space one Mars rocket, for example. .. The launching of very large payloads in one piece into a low earth orbit has the distinct advantage that a large part of the work can be done on the earth, rather than in space.

Exactly how to ignite a thermonuclear micro-explosion by a convergent shockwave produced without a fission trigger is the subject of the new paper, and I’m looking for someone more conversant with fusion than I am to give it a critical reading to be reported here. The basic Orion concept remains in Winterberg’s work with fission bombs replaced by deuterium-tritium fusion bombs being set off behind a large magnetic mirror rather than Orion’s pusher plate.

All Too Little Time

So many papers occurred in different tracks at conflicting times, exacerbated by the need to attend advisory board meetings, so I missed out on a number of good things. I wish I could have attended Kathleen Toerpe’s entire Interstellar Education track, and there were sessions in Becoming an Interstellar Civilization and Life Sciences in Interstellar that looked very promising. I hope in the future the conference organizers will set up video recording capabilities in each track, so that attendees and others can catch up on what they missed.

Several upcoming articles will deal with subjects touched on at 100YSS. Al Jackson is writing up his SETI ideas using extreme astronomical objects, and I’ll be talking about Ken Wisian’s paper on military planning for interstellar flight — Ken and his lovely wife joined Heath Rezabek, Al Jackson, Miles and myself for dinner. The conversation was far-ranging but unfortunately the Friday night restaurant scene was noisy enough that I missed some of it. Miles and I stopped down the street the next night at the Guadalajara, a good Mexican place with a quiet upstairs bar. Great margaritas, and a fine way to close out the conference. Expect an upcoming article from Miles, shown below, on his recent interstellar presentation in a seriously unconventional venue. I’m giving nothing away, but I think you’ll find it an encouraging story.

Three modes of propulsion: it’s nice to have to such options

Some questions for some who might know:

For antimatter storage, the long traps have me stumped a bit.

Are the traps relying on the repulsion of anti-particles themselves

to keep them away from the edges and the regular matter. That would

mean the outermost tubes would still need to have a charge to repel

the anti-matter from them.

Or do the long tubes have a repulsive charge?

In any event, Let us say you can use this long tube storage method. In 50 Years of interstellar travel, There are bound to be high energy collisions. To avoid the eggs in one basket problem , a series of these storage devices would be prudent. Just how far apart should these anti-matter modules from each other to prevent a chain reaction If you were carrying a total of 1 kilo of anti matter to propel a small probe to A-Cent. How would one break it up.

Now I know antimatter/matter collisions have great amounts of energy but there are particles that have more energy (kinetic) contained in them than anti-matter, in fact thousands of times more and they are present in particle beams. Each proton in the LHC at full speed has over 1500 time the energy content of an anti/matter annihilation.

@Micheal – so an anti-proton beam would be even better (assuming that you could extract both the nuclear and kinetic energy of the beam).

@Michael – so what you are really saying is that a particle beam is far more useful than stored anti-matter (3 orders of magnitude). Since we know how to create a particle beam, we should focus on the engineering of scaling this up, rather than looking to use exotic technologies that are inferior in terms of energy density.

It was greatly educational and enjoyable for me to be able to go online and see every presentation of the Icarus Interstellar conference. Heck, I even bought the book. I hope the same sort of publicity accompanies the 100YSS talks.

Great and awesomely inspirational post, Paul!

Regarding antimatter yield, one kilogram of antimatter has the latent energy of 45 billion kilograms of TNT. Here, I am assuming antimatter fuel which could be stored by whatever means and made to interact with the interstellar matter. Ideally, hydrogen anti-hydrogen reactions would be used.

Perhaps we will not find any more invariant mass specific yield fuel besides pure antimatter. If this is the case, no big loss, since we are perhaps limited in antimatter quantities only by the gravitational boundary value of collapse into a black hole. Find a way to produced a layered gravitational shielding mechanism for collecting antimatter, and macroscopic portions of antimatter having the Planck Density would be one suggested limit. A mere cubic meter of this stuff would have a mass of 10 EXP 96 metric tons , a whopping 10 EXP 46 times the total baryonic mass content within our observable universe.

Could we go even more dense? Depends on the scale of space and time quantizement and the details of any valid theories of quantum gravity.

Now folks who are put off by my extreme numbers, take heart. I am not proposing this as a de facto possibility, but instead am just attempting to provide inspiration for those who ponder what may be possible eons from now.

As for near term antimatter production, I’d be happy to see a mere gram of the stuff. Mixed with an equal quantity of normal matter, we have 45 kilotons or about 4 times the yield of the device dropped over Hiroshima. I not advocating militarizing the stuff in strategic weapons, but instead am interested in applications for antimatter induced nuclear fission or fusion for powering starships.

Regardless, today’s TZ-CD story is awesome!

“Exactly how to ignite a thermonuclear micro-explosion by a convergent shockwave produced without a fission trigger is the subject of the new paper, and I’m looking for someone more conversant with fusion than I am to give it a critical reading to be reported here. ”

I’m willing to take a crack at giving it a critical reading, if you will send it forward to me.

Yes, at least 0.07% better! :-)

That seems to make sense, except there is this pesky engineering detail about getting the beam from here to there without losing it. Not that antimatter containment is easy, mind you. But easier? Probably so.

Re. the bothersome issue of containing antimatter, it occurs to me that a radical simplification of the engineering problem would come about were the container itself made of antimatter (perhaps anti-carbon). The advantages are twofold:

a) It then only remains to attach this container in perhaps one place to the craft, using some very localised and stable magnetic coupling – instead of having to contain each and every antimatter particle.

b) The antimatter pressure inside the vessel can be made very much higher than in the conventional containment case – meaning that one can carry a lot more fuel in one container.

Shielding will still be required for the container itself, to protect it from external impinging matter. Oh, and we can’t yet make antimatter elements with ease.

I’m not at all sure what the point of using a fuel that has a hundred times the energy density of fusion is, if the tankage is going to outweigh the fuel a thousand-fold. Penning traps are all well and good for research, but for star ship fuel, we’re going to need condensed anti-matter to exploit that energy density.

Every time I hear of the challenges of producing and storing antimatter I am reminded of a Robert A Heinlein story where they solved this problem by finding a way to change small quantities of matter into antimatter on the ship and then let it annihilate with ordinary matter for propulsion. I have often wondered if there is any glimmer of hope, given the laws of of physics as we understand them, of accomplishing such a thing.

This back and forth about the energy of the beam at the LHC being more practical than anti-matter is a little strange. Taken together matter and antimatter is a fuel that can be converted into energy with 100% efficiency, that energy can be converted to thrust with comparable efficiency. This is the best you can do when bound by the rocket equation. The energy of the protons cycling at the LHC is not implict, it was endowed by a huge draw on the local electric grid which is powered by fuels with a horrendous mass to energy conversion ratio when compared to matter anti-matter reactions. If you want to use protons accelerated to relativist speed for thrust that’s just fine but you still need a source or energy to accelerate the protons in the first place.

A matter anti-matter reaction isn’t the only way to convert all your fuel mass into energy; you can think of the hawking radiation emitted from black holes as the same kind of wholesale conversion of matter into energy. I’m not sure who came up with the idea of using hawking radiation for propulsion first but it was casually explored by Louis Crane and Shawn Westmoreland:

“Are Black Hole Starships Possible”

http://arxiv.org/abs/0908.1803

The basic idea is to instantiate a black hole smaller than an atom with the mass of a large building and deflect the emitted hawking radiation. The authors suggest a bank of gamma ray lasers with intersecting beams to instantiate the black hole. The whole proposition turns out to be less ridiculous than it sounds but it’s still way out there in terms of current engineering capacity and known physics. I believe Jeffrey Lee’s paper in the Propulsion and Energy Track titled

“Fermion Re-Inflation of a Schwarzschild Kugelblitz” was intended to investigate some of the challenges identified by Crane and Westmoreland. Maybe Paul sat in on this one or knows someone who did?

Liquid antihydrogen or antihelium, or a solid like antilithium, then. It helps if we can use magnetic fields for containment – so perhaps anti-iron

If it ever becomes possible to collect significant quantities of antimatter, would it be used for a starship? Wouldn’t it provide an incredibly lucrative source of energy for Earth?

Kyle Owen writes:

Although I had the chance to spend time with Jeff at dinner, along with Eric Davis, I had a schedule conflict and couldn’t be there for his presentation. Jeff also discussed some of these ideas at last year’s Starship Congress, and you can get the video at:

http://www.icarusinterstellar.org/congress-livestream/

And although it’s dated, you might still find this interesting re Crane and Westmoreland:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=10439

Also, John Cody wrote:

The problems of antimatter production and storage are huge, but even tiny amounts can help us with propulsion, especially in hybrid concepts that use antimatter to trigger fission or fusion. If we somehow did have access to large amounts of antimatter (and knew how to contain it), then its uses as a power source would be quite interesting. But production and containment are not going to be easily solved.

Andrew Palfreyman

“… the Icarus Interstellar conference. Heck, I even bought the book. I hope the same sort of publicity accompanies the 100YSS talks.”

100YSS made video’s of the plenary sessions, but not the talks. I don’t know what their plans for releasing them are. I would like to see all of the sessions and workshops broadcast in real time; I don’t expect that to happen any time soon. However they have published proceedings for the last two symposiums:

http://www.amazon.com/Year-Starship-Symposium-Conference-Proceedings/dp/1492386901/ref=sr_1_2?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1411917820&sr=1-2&keywords=100yss

http://www.amazon.com/Starship-Public-Symposium-Conference-Proceedings/dp/0990384004/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1411917820&sr=1-1&keywords=100yss

They are planning on publishing them for this year too. They are also working on proceedings for the first symposium in 2011. I don’t know when the will be available.

I don’t have a schedule on the proceedings either, Matt, but I sure agree with you about the use of video — the track sessions need to be available in an archive.

@James M Essig

My God !! You must have been spying on me or reading my mind or something.

What you said about the use of antimatter stored as the Planck Density in a spherical configuration as a energy source for the spaceship was an idea that I had just about a week ago, I kid you not ! The way I sort of looked at it to add general idea behind what you have already said, was to have an antimatter heavily electrically charged spherical shell centered within an ordinary matter spherical shell.

The way I would look at it is that given what we know about ordinary gravity potential and assuming that the antimatter acts in the same fashion, physically speaking as the ordinary matter component, then you would know that the inner spherical antimatter shell would feel no gravitational force. However, the charged surface of such as shell could be utilized as a buffer against gravitational collapse of the ordinary matter also suitably charged. Such a repulsion would in fact permit shells to be simultaneously peeled off as needed for fuel while retaining the respective balance of forces. Obviously much work would be required for such an idea, but at least you get the general thrust of what is being talked about.

@Kyle

I think that if relativistic particles are 3 orders of magnitude greater energy density, that offer a lot of room for energy conversion to electricity, acceleration efficiency of the particles, loss if matter from beam spread and finally energy extraction from the particles.

It may be that relativistic speeds are not the best approach and that the particles be accelerated to perhaps some lower fraction of c. So perhaps 100x or 10x the energy density is a better target. Also bear in mind that trapping the anti-matter is not going to be costless either.

Naive question. Does it make any sense to use the particles in the solar wind to form the beam. I’m thinking a large magnetic scoop to concentrate the particles before collimating them into a beam. The particle velocity is low (<1000 km/s) but I'm wondering if the scoop size and energy requirements might offer an efficient way to generate a fairly concentrated beam that would be better at accelerating an electric or mag sail than the solar wind alone. Add some particle acceleration and it might still offer better performance than an anti-matter rocket (at least within the solar system).

“one of the biggest problems with putting a probe around another star is data return”

I have thought (and posted at NBF) about the feasibility of a dual purpose system of smaller and more numerous laser stations positioned through-out the solar system. Each station would be used for inter-system sail travel, as well as for launching small (~10m2), cheap, sails multiple times a day in a continuous stream towards Alpha Centauri. For a velocity of 5% of c, twice daily launches would make for a distance between mini-sails of ~90 au.

In time a line of mini-sails would stretch between star systems. Each mini-sail would be capable of sending and receiving data by laser to the next few mini-sails in the stream. That way data transfer could be sampled by multiple craft to ensure data accuracy and completness. No need for high mass communications equipment. An additional benefit would be redundancy in the event of any one mini-sail failure.

A stream of mini-sails would also solve the problem of how to stop at the target star. As each mini-sail passed through at full speed, sending data back through the line, a new mini-sail would be right behind. The effect would be similar to having a larger probe come to a halt and taking station in orbit about the star. Not needing to decelerate also cuts the transit time between stars in half.

Dual tasking the lasers doubles the return on investment. As each laser station waits for its’ turn to accelerate a mini-sail out of our system, it could be used to accelerate/decelerate inter-system traffic. Not only is a long term study of Alpha Centauri enabled in this way, but an infrastructure for high speed inter-system transit is also established.

Time Dilation Confirmed in the Lab

by SHANNON HALL on SEPTEMBER 29, 2014

It sounds like science fiction, but the time you experience between two events depends directly on the path you take through the universe. In other words, Einstein’s theory of special relativity postulates that a person traveling in a high-speed rocket would age more slowly than people back on Earth.

Although few physicists doubt Einstein was right, it’s crucial to verify time dilation to the best possible accuracy. Now, an international team of researchers, including Nobel laureate Theodor Hänsch, director of the Max Planck optics institute, has done just this.

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/114879/time-flies-in-the-lab/

IKNOW*:

Great idea! See also here:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=10176#comment-75988

You, sir, (or ma’am) exhibit an extraordinarily high degree of intelligence and creativity.

Beyond the idea of shrunk junk chuckin’…

Though the mini-sails would represent a much smaller mass, the total beam power required for acceleration to a significant fraction of c would still be on the order of 100’s of gigawatts. Breaking a single beam station down into multiples distributed through out the solar system would make construction and maintenance of each station far less complex. And, allow for their use as an inter-system transport infrastructure. It’s in this diversity of function that, I believe, a project of this magnitude could be justified.

IKNOW* said…

“A stream of mini-sails would also solve the problem of how to stop at the target star. As each mini-sail passed through at full speed, sending data back through the line, a new mini-sail would be right behind. The effect would be similar to having a larger probe come to a halt and taking station in orbit about the star. Not needing to decelerate also cuts the transit time between stars in half.”

You can have your cake and eat it. If you’re launching probes every 12 hours and factoring redundancy, then why not design the first 3 months-worth of probes (180 probes should allow for any losses(?) ) to do the midway flip and decelerate for system exploration. The 181st probe then becomes the first probe designated the lead scout for the rest of the flotilla stream that will constitute the fly-through data analysis mission segment; they’ll overtake the first 180 probes as they decelerate and would get there years in advance allowing tracking planets in their orbits from the vantage points along their trajectory through the system. The 180 explorers then get all the data they’ll need as they decelerate. The more distant targeted stellar systems will provide more pre-exploration data prior to system exploration due to the mid-journey flip ocurring later. Many more orbital data points could be accrued from the longer duration stream of data-gatherers.

Mark Zambelli says…

“…to do the midway flip and decelerate for system exploration.”

Having slower, larger sails would allow them to be used as data relays. Any probes launched at lower velocities would be passed up by the first full speed mini-sails well before the half way point. At any significant value of c, the first fast craft could begin arriving decades before the larger relay sails.

Any craft intending to slow into the target star system, regardless of size, would require a method to do so. That means either a preplaced beam source or using some aspect of the stars ambient environment to decelerate.

There may be a few ways to bring the first, and occasionally subsequent, sails to a slower velocity. If you’ve never seen ants form an ant raft, its when a group of ants interlock with each other to create a floating raft to survive floods or form a floating bridge. If some of the mini-sails consisted of inter-linked micro-probes, then apon aproach to the target star, they could disengage from one another, unzipping to create a long electro-statically charged filament and utilize the stellar wind to slow down, then zip back up to their original shape.

Some mini-sails could disengage from one another to become a cloud of micro-probes which would take divergent paths through the star system. Due to variances in the gravity and stellar wind, the smart motes would envitably travel at different speeds, on different paths.

The dust motes would be limited in their capacity to do much more than relay their own positions, however their changes of position relative to one another would provide some gravimetric data that could help locate larger bodies in orbit around the star, as well as help characterize the stellar winds. This info, arriving at Eath some four and a half years later, could be used to plot courses for later mini-sails through the target star system. Course adjustments of the smallest degree made during the acelleration period would translate to widely seperate points of entry into the target system.

As time passes, material technology will continue to evolve. Newer, better designed, more robust, more capable mini-sails would replace those of the original designs. The evolving mini-sails no doubt would be able to take higher levels of beam power equating to higher fractions of c. That alone would be an immense advantage over a single large sail which, due to production lead times, would be obsolete by then-current standards at the time of launch.

The multitude of smaller laser stations would be hard pressed to push larger sails to inter-stellar speeds, but they would provide an infrastructure for fast interplanetary transport. This duality of fuction makes the mini-sails approach an easier sell to those with the purse strings, than a one shot you-will-never-see-the-benefit solid gold frisbee to the stars.

As Kyle Owen pointed out above, the huge power requirements needed for the LHC beams is prohibitive for making an antimatter drive from particles. There is also the matter of how much H2 the LHC uses for the protons in the beam.

Details can be found here http://www.lhc-closer.es/1/3/10/0 but the gist is this… the LHC protons are fed into the ring from a standard 5kg Hydrogen bottle twice a day. With the hundreds of billions of protons needed for the small percent of collisions each second, the 5kg H2 bottle will provide enough protons to keep the whole LHC running constantly for over 4 billion years!

In order to produce propulsion from an anti-proton/proton beam then surely this will have to be scaled up many orders of magnitude and the collision rate upped too from the paltry <<1%. I'm not too hopeful that this system would be of any use as a method of propulsion.

I love the idea of using anti-iron… provided of course that anti-iron is ferromagnetic like normal-iron (probably is but with us still not knowing for certain yet whether anti-matter would fall up or down in a gravity well http://physics.aps.org/synopsis-for/10.1103/PhysRevLett.112.121102 we don't know for sure).

Making larger nuclei (other than protons) from antimatter is going to be many orders of magnitude more difficult than making antiprotons. I am afraid we are stuck with anti-hydrogen, and if we want dense fuel storage we will have to condense and supercool it to liquid or solid form and handle it remotely with the forces that can be mustered by dielectric and/or diamagnetic interactions.

A large blob of liquid hydrogen might be stable in space if kept in perfect shade, all the time. If you hit it carefully with a tiny puff of normal matter on one side, you might be able to have controlled annihilation that will propel the blob. Station a ring-shaped normal matter habitat around it by diamagnetic interaction, and you have your antimatter starship. Acceleration is not going to be great, but it could be quite efficient. The trick is going to be keeping evaporation down in the face of heat that is certain to be generated by the annihilation.

Perhaps instead of annihilating directly at the surface of the blob, a stream of neutral anti-hydrogen could be gently evaporated from the blob by laser heating, allowed to flow into a nearby magnetic nozzle and annihilated there, with the nozzle keeping the reaction products from heating the blob.