Back in 1950, George Pal produced Destination Moon, a movie that was based (extremely loosely) on Robert Heinlein’s Rocketship Galileo. Under the direction of Irving Pichel, the film explained the basics of a journey to the Moon — using among other things an animated science lesson — to a world becoming intrigued with space travel. I’ve wondered in the past whether we might one day have an interstellar equivalent of this film, a look at ways of mounting a star mission in keeping with the laws of classical mechanics. Call it Destination Alpha Centauri or some such and let’s see what we get.

Christopher Nolan’s film Interstellar doesn’t seem to be that movie, at least based on everything I’ve seen about it so far. I did think the early trailers were interesting, evoking the human urge to overcome enormous obstacles and buzzing with a kind of Apollo-era triumphalism. The most recent trailer looks like starflight is again reduced to magic, although maybe there will be some attempt to explain how what seems to be wormhole transit works. While we wait to find out, I still wonder about what kind of mission we would mount if we really did have a world-ending scenario on our hands that demanded an interstellar trip soon.

[Addendum]: I’ve been reminded that Kip Thorne has a hand in the science of this film, which does make me more interested in seeing it.]

Dana Andrews, as we saw yesterday, has been exploring a near-term interstellar colony ship that could fit into this scenario. Today I want to return to the paper he presented at the recent International Astronautical Congress. Andrews defines near-term this way:

Near-term means we can’t use warp drive, fusion engines, or multi-hundred terawatt lasers (which could destroy civilization on Earth in the wrong hands). Affordable means we’re going to do design and cost trades and select the lowest risk option with reasonable costs…. The goal was to design the system with state of the art technologies, assuming there will be twenty to thirty years of Research and Development before we start construction.

I speculated yesterday that given the need for a robust space-based infrastructure, it was hard to see the methods Andrews studies being turned to the construction of an actual starship before at least 2070, but it’s probably best to leave chronologies out of the picture since every year further out makes prediction that much more likely to be wrong.

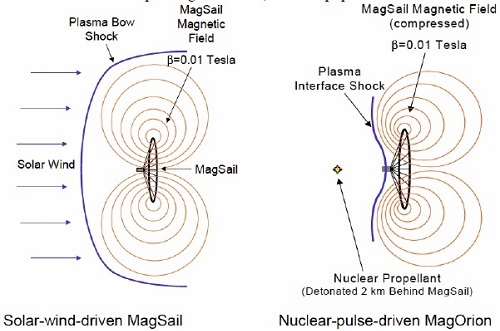

The ‘straw man point of departure’ design in Andrews’ paper invoked beamed lasers mounted on an asteroid for risk stabilization and momentum control, with a 500 meter Fresnel lens directing the beam to the spacecraft’s laser reflectors, where it is focused on solar panels to power up ion thrusters using hydrogen propellant. A 32-day boost period gets the mission underway and a magsail is used to slow from 2 percent of c upon arrival. Andrews is assuming a laser output of around 100 TW to make this system work.

Enter the Sailbeam

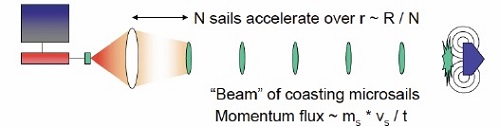

But the point-of-departure method is only one possibility Andrews addresses. He also looks at Jordin Kare’s Sailbeam concept, in which a large laser array (250 5.8 TW lasers) accelerates, one after another, a vast number of 20 centimeter spinning microsails. The acceleration is a blinding 30 million gees over a period of 244 milliseconds, with the ‘beam’ being kept tight during the brief acceleration by using ‘fast acting off axis lasers,’ and additional lasers downrange. Only for the first 977 kilometers are the sails actually under the beam.

Image: The Sailbeam propulsion schematic. Credit: Dana Andrews.

Notice the requirement for keeping the beam tight, an issue that has bedeviled concepts from laser-pushed lightsails to particle beam acceleration. After all, beam spread means you can’t deliver the bulk of the required power to the vessel that needs its energies. Assuming a tight microsail beam, however, the huge boost delivered at the beginning is sufficient, according to Kare’s numbers, to produce serious thrust for the starship. The beam reaches the ship, which vaporizes and ionizes the incoming sails by its own laser system, creating a plasma pulse that drives a magsail. Numerous issues arise with this method, as Andrews describes:

250 micro sails per second amounts to 3.2 kg/sec, and that requires 150 to 300 MW of laser power to ionize the microsails. Assuming 50% efficient lasers we need about a gigawatt of thermal power. Assuming risk factor three, that’s about 1000 mT of powerplant mass, which is actually less than the laser-powered ion propulsion system.

Could we beam the needed power to the ship? Perhaps, but there are other problems:

To maintain 0.01 gee with 250 microsails/second as the spacecraft approaches 2% c, we need to accelerate each microsail for 0.18 seconds. Since we assume each microsail launcher needs about 0.5 seconds to place, align, and spin up its microsail, we don’t need to increase the number of laser launchers to maintain the 0.01 gee. The problem is the long (730 day) acceleration time, which results in end of boost at 1238 AU. This requires very small sailbeam divergence (< Nano radian).

Image: Microsail plasma interaction magsail dipole field. Credit: Dana Andrews.

With regard to the divergence problem, you’ll remember our recent discussions about neutral particle beams, which occurred in the context of Alan Mole’s paper in JBIS on a small interstellar probe. Mole, in turn, had drawn on earlier work by Andrews in 1994. In that paper, Andrews described a 2000 kilogram probe driven by a neutral particle beam sent to a magsail (the same magsail would be used for deceleration in the destination system). Writing in these pages, James Benford later found this propulsion method inapplicable for interstellar uses because of unavoidable spread of the beam and a corresponding loss of efficiency, although he considered it quite interesting as a driver for fast interplanetary travel.

In the current paper, Andrews revisits particle beam propulsion as a third alternative to the ion thrusters in his point-of-departure design. He cites Benford’s critique in the footnotes and goes on to add that the divergence of the beam will limit the useful range of operation. That implies high accelerations at the beginning of the flight, when the spacecraft can exploit maximum power from the beam as it meets the required divergence angle requirements. To catch up on our Centauri Dreams discussions of these issues, start with The Probe and the Particle Beam and Sails Driven by Diverging Neutral Particle Beams, both of which launched discussions and follow-up articles that can be found in the archives.

But there is a final possibility, the laser-driven lightsail as envisioned by Robert Forward back in the 1960s and refined by him in numerous papers in the years following. Which of these best fits our need to launch a near-term mission aboard a crewed starship? More on the laser lightsail and Andrews’ thoughts on energy requirements when I wrap up the paper tomorrow.

The paper is Andrews, “Defining a Near-Term Interstellar Colony Ship,” presented at IAC 2014 (Toronto) and in preparation for submission to Acta Astronautica. The earlier Andrews paper is “Cost considerations for interstellar missions,” Acta Astronautica 34, pp. 357-365,1994. Alan Mole’s paper is “One Kilogram Interstellar Colony Mission,” Journal of the British Interplanetary Society Vol. 66, No. 12, 381-387 (available in its original issue through JBIS).

I believe that both quantum and classical mechanics must wed (or be supplanted by better theories) if we’re intending on maximizing the potential of interstellar capabilities for 70-100y human lifespans–mainly in deciding whether or not we need exotic matter (i.e. negative masses ala Morris-Throne types “Interstellar” will probably be based on) or real evidence (and access) to varying cosmological string types; as both of these concepts allow the possibility of traversable wormholes. Without them, we’re very crudely stuck with what we’ve got. Doesn’t look pretty, but on the bright side, we (and many other organisms) still have hundreds of millions of years to work with, barring the worst. The equations allow the possibility, but in reality its no more real or fake than the Bajoran wormhole of Deep Space 9, or “red matter” in the 2009 Star Trek film, since none of them are currently testable. :(

Really, traversable wormholes exist solely as theoretical objects to examine the depths of general relativity, and although there appears to be a lot of theoretical material on creating solutions by adding different environments with exotic matter, we have yet to encounter it. As for the film, I wouldn’t knock it just yet, without a proper view. Thorne is exec producer and contributed to the scientific aspects of the film. Doubt he’d let his reputation be clouded by magic.^^

Hi Paul,

The various interstellar propulsion systems mentioned are very interesting however one common problem they all share is none address how they will get the large amounts of hardware 100Km or so above the Earth’s surface. If the thought is to use chemical rockets to launch the ship parts into orbit to make up the interstellar ship then all these designs most likely will not happen due to astronomical costs and shear logistics (ie unfeasible time and money required).

Assuming some kind of space shipyard will be setup in the future doesn’t solve the problem as the shipyard has to be built and supplied in the first place. Looking at how long it took to build the International Space Station in LEO is just an example. From what I’ve gathered so far it is highly unlikely a space elevator will be built for at least another 50 years (if it turns out to be feasible).

My point is as long as we rely on chemical rockets to get hardware into orbit it is highly likely we will be restricted to solar system only exploration for the forseeable future.

Cheers, Paul.

0.02 C is nothing to sneeze at. We could perhaps launch such spacecraft in droves all over the galaxy.

I enjoy the concept of 0.02 C space-arks because they are a deep time oriented project.

Now, if a means of slowing time down in the spacecraft frame outside of the usual constraints of Special Relativity, that would be better yet. Here, I an not considering general relativistic effects such as approximations to the Schwarzschild metric, but rather some other effect that would not require a huge mass and density.

Regardless, I am pleased that folks are coming up with conceptual details of potential star-faring enabling hardware.

Joëlle B. writes:

Had forgotten about Thorne’s involvement. That does make it more interesting.

.02 C is too slow for one reason: it will take over 200 years to get to the Alpha Centauri system at that speed. Surely within 200 years after launch we will figure out and build the infrastructure necessary for the launch other, more advanced ships going much faster, which will pass the first one and leave it in the (interstellar) dust. A lot of time and money will be wasted on the first ship.

The problem with wormhole travel or the Alcubierre drive is the whole causality thing. Even if negative energy density is discovered and manipulated; even if inventive space-time metrics allow people to travel faster than light on technicality; those ideas necessarily allow a reference point where the traveller arrives before he departs. There would be a configuration of such a system which allows backwards time travel. Ergo, the whole technique doesn’t physically make sense. That’s probably why we haven’t seen negative energy density in macrophysics in the first place. It’s fantasy.

Problems with interstellar travel are oppressive not because they are too complex, but because they are too simple. Out in the vast vacuum of space, very basic equations explain the behavior of objects. Newton and Einstein seem to have nailed it down. There is so little to take advantage of; so few ways to squeeze a bit more ?v out of a spacecraft within reasonable propellant-to-payload ratios, even with insanely advanced propulsion methods. Reactionless and space-warping methods are turning out to be crackpot fantasies. Unfortunately, we may have to face the ugly truth that ambitious space travel was not meant for beings as short-lived as ourselves.

I think it’s quaint of us to try to figure out how to go there within natural human lifespans. That’s the ambiguous variable. We’re guilty of the same mistakes early science fiction writers made: we lack foresight, and we are naive. We are thinking up the next retro-future that fails to happen for dreary, practical reasons. Interstellar travel will be enjoyed by post-people who have solved far more manageable problems, like mind uploading or highly advanced cybernetics and genetic engineering. People who have machines that save their synapses and let them ignore tens of thousands years. People who won’t goofily attempt to warp space into inverted shapes just to get to the next star in a scant couple of years.

Huh, I saw George Pal’s Destination Moon not too long ago… I hope that any modern interstellar equivalent will base itself upon a more engaging storyline than Destination Moon. You know there is something wrong when an animated science short is the most exciting part of a film. :) At this point it is an interesting cultural relic of the pre-Apollo days, though.

Don’t get me wrong- I’d love to see a SF movie portraying an interstellar expedition based firmly on real mechanics, not fantasy. All sorts of interesting ideas can spin out of the human realities of such a voyage.

Ion drives, nuclear pulse propulsion, laser sails, sail-beams… the funny thing about space propulsion systems is that you realize after a while that they all do one of two things: throw something out the back to move the craft forward, or throw things at the craft to transfer momentum to it. Momentum, and its conservation, is at the core of space propulsion- be they closed systems like rockets or open systems like sails etc.

A couple of things.

1. Destination Moon was actually originated by Robert Heinlein as a screenplay or at least a screen treatment. Rocket Ship Galileo and The Man Who Sold the Moon both influenced the story, however Heinlein published a novella in 1950 in Short Stories magazine called Destination Moon. From his biography we know Heinlein was contacted by the famous director Fritz Lang about some kind of ‘space’ movie, but the deal never happened. However Heinlein teamed with screenwriter Rip Van Ronkel and interested George Pal in the story. Even tho Heinlein is listed as a screenplay writer it is James O’Hanlon and van Ronkel who wrote it. However Heinlein was also technical adviser and he liked the director Irving Pichel who eliminated some silly stuff that almost went into the film. Heinlein was pleased with the finished product but even with success of the film it took a long time to get paid for his services. He had even harder luck with Hollywood and TV , but that’s an old story for writers dealing with the visual media.

2. In was Carl Sagan’s involvement of Kip Thorne , trying to get some new viable interstellar transport idea for CONTACT that got traversable wormholes invented. They are used in both the novel and even mentioned in the movie. That apparently inspired Kip to write a treatment for another story using a wormhole, that was picked up by Steven Spielberg but handed off to Christopher Nolan. Nolan has proved to be a serious film maker so I expect Interstellar not to be ‘silly Hollywood’ stuff, tho must admit from the previews, there seems a worn out pre-apocliptic air to the first part of the film, so me-thinks the story will be only kinda sorta ok.

Interesting Matthew McConaughey was in CONTACT and now will be the lead star of INTERSTELLAR.

(Making INTERSTELLAR … CONTACT 1.5!)

JBE said on October 7, 2014 at 19:38:

“0.02 C is too slow for one reason: it will take over 200 years to get to the Alpha Centauri system at that speed. Surely within 200 years after launch we will figure out and build the infrastructure necessary for the launch other, more advanced ships going much faster, which will pass the first one and leave it in the (interstellar) dust. A lot of time and money will be wasted on the first ship.”

But will we? I read that a lot every time a “slow” starship is brought up. Right now the best we can do is about 77,000 years to Alpha Centauri and of course none of the five probes leaving our Sol system are headed in that direction anyway. Two centuries seems like a bargain.

We have NO guarantee that a faster ship will come along any time soon, especially if you are hoping for some kind of FTL drive. The latter is more than just a few technical problems; there are major issues regarding the physical laws of the Universe – and no they will not just go away in time, either.

We rely too much on these ambiguous (and nonexistent) future smart people who are supposed to solve all our problems. There is no guarantee that society will get better and allow people to pursue interstellar technology development. We were supposed to manned lunar and Mars bases by now, according to people back in the early Space Age who assumed their descendants would logically follow up on their grand space plans. Well here we are in their future and so far zip to any kind of actual space colony from any nation.

If we waited for the technology to improve we would probably never had Apollo. Those missions returned almost 500 pounds of lunar regolith and rocks which we are still learning from thanks to technology and knowledge they did not have 45 years ago. But without those missions gathering so much material for science in the first place, we probably would have had to make due with the few ounces returned from the Soviet Luna missions.

The same with the Pioneer and Voyager probes. They were launched in the 1970s and not meant to last much beyond their outer planet targets. But here we are decades later still gathering data on the very outer Sol system and the shores of interstellar space despite their “old” technology and relatively slow speeds.

You will note that not only do we not have any actual starships on the proverbial drawing boards, we do not even have any new missions for exploring even nearby interstellar space beyond a lot of talk and CGI drawings at this time. I will take a real and slow deep space mission over waiting and hoping for someone to build a warp drive that will get us to Alpha Centauri in a few hours “some day in the future.” That is what we and every interstellar and related space group should be focusing on, real possibilities and real technologies, not Star Trek. Otherwise our interstellar dreams will remain just as fictional.

I will be curious to see how much the makers of Interstellar actually listened to Kip Thorne. Most filmmakers will tell you the story comes first, reality second and only then if it works into their plot. And we are dealing with “magical” warp/FTL drive here, so any reality is already on pretty thin ice.

Carolyn Porco of Cassini Saturn science fame was asked to be the science consultant on the first Star Trek film made by J. J. Abrams. She was asked just one question: What would the USS Enterprise look like coming out of the atmosphere of Titan? I also recall an article by a former Star Trek writer who was told by a producer to knock it off regarding adding any fancy science knowledge to the script. Even the venerable 2001: A Space Odyssey ditched scientific knowledge and technical realism in several cases where aesthetic appeal won out.

Al Jackson writes:

First-rate, Al. Thanks — I love to get the deep background on stories like this, and you’re just the guy to deliver it. I’d didn’t know about that 1950 novella in Short Stories. On other background, ‘The Man Who Sold the Moon’ seems more in the spirit of the movie than Rocket Ship Galileo, though as you show, both were just influences.

Paul Titze writes:

I wouldn’t count out Elon Musk’s SpaceX aims to bring their first and second stages back to Earth for reuse. There is video of them doing just that in the middle of the Atlantic before a wave knocked the first stage over.

I find SpaceX endlessly fascinating as what they are doing is what Rocketships are meant to do. In retrospect we may see the disposable rocket age as a huge boondoogle for the Aerospace companies.

If SpaceX can bring them back to a platform or to the launch site then the economics all change.

ljk

Supposedly Thorne has a cameo in the film, but I don’t know how much explaining the do. Hollywood is addicted to Techno-Babble (god knows why!).

All the great SF writers learned to eschew Techno-Babble when J.W. Campbell became editor of Astounding in 1938. It has served well since that time, just show the readers how it work, don’t tell em about how to use the clutch, shifting gears or how to use the breaks… when it’s super science just make it tenable with reasonable sophisticated language about extrapolated technology.

The film Gravity was an odd bird JPL vet Kevin Grazier was the technical adviser and even tho NASA refused to help (I think they actually changed their mind after the film came out) there was a lot of under-the-table info.

Grazier says he did note all the ‘funnies’ about the story and the Cuaróns did write 30 pages of ‘fix-up’ , but when push came to shove in filming they had to discard all that for pacing. I wish a good SF writer had of been consulted, and had of suggested and the won the battle of having the opening credits mention that the story was set in an ALTERNATE UNIVERSE IN THE FUTURE. That would have been a good fix up. ( Wikipedia even listed it that way for a little while but deleted ‘alternate universe’.)

After all the Tiangong will not be that complete until about 2025 and that in future.

My friends at JSC was amazed at the interior spacecraft details in Gravity. The Soyuz cockpit even had the manuals in the right place. Lot’s of physics details about Gravity are right even when they are about a million standard deviations out in the tail of the distribution as problem solutions.

@ljk Even the venerable 2001: A Space Odyssey ditched scientific knowledge and technical realism in several cases where aesthetic appeal won out.

Do you have specifics – i.e. what was in the script but abandoned in favor of aesthetics? Given that Clarke was co-writing the screenplay and the novel. and that much of the hardware was designed by technical experts, e.g. Ordway, I find that statement a little hard to fathom. Mistakes were made, but AFAIK relatively few. But deliberate errors for aesthetic reasons?

I’m not sure that Kip Thorne’s involvement in Interstellar is all that important. If it involves space warps and even time travel, these are merely mathematical ideas that allow the plot to move forward without the annoyances of reality as we currently understand it based on evidence.

I hope that Interstellar proves as entertaining and interesting as Inception. But it might be as scientifically accurate as The Prestige. Given how misleading trailers can be, I’ll wait for the movie to release.

I am not so sure that accelerating these discs by laser would be a good idea, would the discs after been heated act as radiators which cause a dispersion issue. I am in favour of a particle beam railroad system as mentioned in A.C in numerous posts from orbiting revolving habitats based all over the solar system.

Al Jackson said on October 8, 2014 at 11:12:

“Supposedly Thorne has a cameo in the film, but I don’t know how much explaining the do. Hollywood is addicted to Techno-Babble (god knows why!).”

I would love to think Thorne being in the film means something, but I remain skeptical unfortunately. As for technobabble, why what would Star Trek do without it? :^)

http://en.memory-alpha.org/wiki/Technobabble

http://www.themarysue.com/technobabble-list/

My favorite Treknobabble is the Heisenberg compensator as the essential tech for the transporter. When asked how it works, Mike Okuda replied “They work just fine, thank you.”

Then Al said:

“The film Gravity was an odd bird JPL vet Kevin Grazier was the technical adviser and even tho NASA refused to help (I think they actually changed their mind after the film came out) there was a lot of under-the-table info.”

There was a lot wrong with Gravity, including the fact it was very anti-space. Sandra Bullock’s character should never have been allowed on a space mission with her psychological background and what was she doing working on the Hubble Space Telescope being a biomedical engineer?

Yes it was nice that they were so detailed on the spacecraft, but everything else was bogus and negative, not to mention incredibly hostile and deadly to every single vessel and human in the vicinity. Of course all is well only when she makes it back to Mother Earth, being reborn from the water no less. NASA was wise to stay away from this film; the makers probably would have ignored them anyway in their goal to make sure space is not the place.

http://www.wired.com/2013/10/neil-degrasse-tyson-gravity/

Thomas Thorne said; “The problem with wormhole travel or the Alcubierre drive is the whole causality thing. ”

You might be interested to read this page on wormholes and causality from Orion’s Arm; it was written by Jim Wisniewski, who also wrote the Hawking Radiation calculator page.

http://www.orionsarm.com/xcms.php?r=oa-page&page=gen_wormholescausality

Basically, not all wormhole configurations breach causality, so long as you keep the wormhole mouths far outside each other’s light cones.

Alex Tolley said on October 8, 2014 at 11:45:

@ljk Even the venerable 2001: A Space Odyssey ditched scientific knowledge and technical realism in several cases where aesthetic appeal won out.

“Do you have specifics – i.e. what was in the script but abandoned in favor of aesthetics? Given that Clarke was co-writing the screenplay and the novel. and that much of the hardware was designed by technical experts, e.g. Ordway, I find that statement a little hard to fathom. Mistakes were made, but AFAIK relatively few. But deliberate errors for aesthetic reasons?”

So glad you asked! I can give you two big examples right off the bat:

The lunar surface was depicted as craggy and rough, just like most people thought it would look in those pre-Apollo days. The trouble is, astronomers knew the lunar mountains were smooth and rounded, not Bonestell pointy and bouldery. Even Arthur C. Clarke knew and the proof lies in his 1964 book Man and Space from the Time-Life Science Series. I distinctly recall the diagrams included which showed what the lunar mountains really looked like and the old version side-by-side. So 2001 did know what the Moon looked like up close, but they chose to go with the mythical version because the majority of the audience were exposed to centuries of a rough lunar surface.

The other biggie is the design of the USS Discovery. Being nuclear powered, it should have had vanes to dissipate all the heat being generated by the engines. Early design art even had those vanes. The problem was it made the Discovery look like it had wings, so the vanes were removed for aesthetic purposes and movie magic kept the nuclear reactor from melting and destroying the ship and everyone in it.

Here are a few of the early production designs for the Discovery with the “wings” attached:

http://rainingfishes.wordpress.com/tag/2001-a-space-odyssey/

http://members.tripod.com/aries_1b/id29.htm

Early on Kubrick et al considered having the Discovery be an Orion nuclear pulse spaceship. I think that would have been very interesting to see.

Whoops, here is a much better page showing the early Discovery concepts:

http://members.tripod.com/aries_1b/id46.htm

I wonder if these could be extrapolated into real starship designs?

@Thomas Thorne

Things don’t necessarily have to make any sense at all for them to be a part of the universe–quantum mechanics teaches us this very boldly (ex. the probabilistic nature of the wave function and subjective nature of each observation, making it quite difficult to determine cause and predict effect from a classical notion, as well as violations of Bell’s inequalities). We shouldn’t care if things weird us out or appear to be retrocausal, especially if time derives itself from a quantum source (i.e., entanglement) and defies the erroneous conjecture of local realism, of which much of relativistic effect depends upon. We should just continue wiping away at spacetime’s dirty crevasse, while being mindful to “shut up and calculate”.

Furthermore, we’d be wise to use our increasing knowledge of nonlocality to inquire the extents of what our relativistic state has deceived us into believing and first, maybe, start putting predictions to the test that aim at probing when superposition of the eigenstates become apparent for (us) observables, which would ultimately give us a clearer outlook on how to tackle the interpretational issues that have given way to an extremely diverse, yet rich, physics community. In doing so, we will be better prepared to decide what forms we should be willing to take and what their repercussions may be: a long life, even biological immortality, mean nothing if fragile and superficial. I’m the first one to jump on the genetic engineering train, but whenever I bring it up the same people who think “post” humans will identify themselves differently than us with superior intelligence and capability think that it would be possible without amalgamating different branches of the evolutionary tree–somehow animals will make us so “post” that we will lose something they think is worth holding onto, idk.

& @ljk

Likewise, since the positive energy condition isn’t required for mathematical consistency of Einstein’s equations, along with violations of the weak energy condition in Casimir vacuum of quantum field states, I definately don’t think “magic” (in a metaphysical sense) necessitates an accurate depiction of a wormhole, as discussed by Visser, Morris, Yurtsever and Thorne. We know what we should look for; it isn’t pseudo-science, and all of us can contribute to tackling the problem so we don’t waste our time. Ultimately, if it comes down to not working at all, we still know what we’re trying to accomplish, and still have the time and tools to keep trying. I keep Marc’s paper “Progress in revolutionary propulsion physics” (http://arxiv.org/abs/1101.1063) bookmarked to aid in focusing on what direction I should keep my eyes open and what I should search for to see if any new informational breakthrough has become available on the web. Figure 1 and Table 1 on pages 4 & 5 should prove to be useful resources.

Mainly, Einstein’s philosphy of realism and appreciation of aesthetic simplicity influenced his work, just as much as Bohr, Schrödinger, Bohm and Pauli’s views influenced theirs and the whole “quantum mysticism” controversy, still seen in the works of Roger Penrose and Max Tegmark (to a lesser degree) in varying ‘quantum mind’ or “Consciousness as Matter” schools of thought. I think you will enjoy reading this: http://www.academia.edu/260503/_Mysticism_in_quantum_mechanics_the_forgotten_controversy_

Yes, 200 years is a beastly improvement in comparison to 70k. We need to keep our minds open and stay optimistic. Belittling evolutionary history by using social undermining towards the potentiality of life in any form will not solve anything and is why people become afraid to do things like Apollo. Just get out there with some buddies and break the universe to better figure out its limits, even if someone says it’s impossible. I never cease to be amazed.

@ljk – I should have recalled the heat sinks perceived as “wings” issue. I recall Clarke discussing this issue in one of his books. The problem was that novel described Discovery as looking like a dragonfly. They could have overcome the wing look by other means, e,g, making the radiators more like circular blinds as depicted in one of the BIS books for a nuclear spaceship.

As for the lunar landscape, I didn’t realize that. Although my copy is inaccessible at the moment, I think I recall the imagery you mention. Since Surveyor 1 was on the moon in 1966 providing surface pictures, there were no excuses. Just aesthetics influenced by Bonestell among others. The jagged lunar landscape imagery took a long time to die, persisting in SF book covers for decades after the ground truth was known.

ljk

Just a note.

I returned last weekend from the 65 International Astronautical Congress (biggest space gathering I know of) in Toronto.

The Canadian Space Society had , on Thursday night, a special tribute to Fredrick Ordway , the main technical adviser on 2001. Fred died this year not many months ago. Ordway spent almost 3 years working on the film and is main reason the designs and spacecraft passed into an alternate universe in 2001!

Ordway was an engineer and space historian and very special person.

For propulsion I like the idea of a Thorium fueled dusty plasma fission fragment rocket. Fairly near term tech, Thorium being fertile rather than fissile you don’t have the criticality issues that U235 presents, no actual tankage at all, really. A molten salt Thorium reactor could surround the plasma chamber, with the U233 continually extracted from the salt and injected into the chamber as dust. Fission wastes that end up in the salt could be used as ion drive fuel, using the plentiful thermal cycle power the reactor would generate.

While Thorium reactors have to be very efficient in their utilization of neutrons to keep the reaction going, the Thorium fuel could be ‘salted’ with extra U235 to make up the difference. It wouldn’t require enough to risk criticality in the fuel stores, with the Thorium soaking up the decay neutrons so efficiently.

My soft spot is for Project Longshot engines. On-board fission reactor that drives a fusion engine. The fact that we can’t contain plasma well becomes irrelevant, as hot plasma squirting out the back is exactly what we want for a rocket.

drs

Just to clarify the Project Longshot engines were “Daedalus” style self-exciting fusion engines. A fission reactor powered up a flywheel for the initial start-up in the Longshot version (which isn’t sufficient as the power required was 10 petawatts – too high for a flywheel.) While firing the main drive directly powered its own electron-beam igniters via an induction loop tapping the massive plasma current flowing out of the engine.

The original “Discovery II” fusion vehicle design came closest to a fusion vehicle with a fission start-up, but the heat-load was too high, so the acceleration was poor. The next iteration was self-sustaining using polarised 3He+D fuel to improve the cross-section.

Adam

Brett Bellmore,

The system you describe is far too complex and suffers horribly from heat management issues. A basic fission fragment system ejects fission products directly and minimises x-ray heating and neutron bombardment by a fairly transparent design. Pavel Tsvetkov’s Magnetic Collimator Reactor is the system to think of when discussing high performance FF rockets.

“I still wonder about what kind of mission we would mount if we really did have a world-ending scenario on our hands that demanded an interstellar trip soon.”

Sorry, Paul, disagree with you. If there was a world-ending scenario, the last thing on most people’s minds would be launching an interstellar trip. And if some sort of salvation was perceived in space, then the destination would surely be Mars.

Stephen

Adam, have you looked at the problems inherent in storing fissile elements in large quantities? For a high delta-v, U235 would have to comprise most of the mass of of the starship at departure! But it goes “boom” if you pile more than a few pounds in one place.

You end up having to carry your fuel in the form of long wires hung around the craft, or in some other physically dispersed arrangement, to avoid criticality, because you just can’t afford the weight of shielding necessary to store it compactly.

No, I think generating the fissile fuel enroute from a fertile element is the way to solve this problem.

As soon as they can, the superich will build their own space colony probably using a hollowed out planetoid or maybe a comet. They will also have some form of propulsion attached to one end of it to make a getaway, probably to avoid paying interplanetary taxes.

Once again, our first human interstellar adventurers will probably be anything but noble, straight-laced NASA astronauts. Think the first types of people to come to the New World, or Australia.

Brett Bellmore and Adam are right. Fission fragment rockets are our most realistic option to reach a few percent of c, soon.

Actually, I think Orion is the most realistic, calculated to be capable of 3% of C, and providing a hugely higher acceleration, meaning that most of the trip would be cruising at 0.03 C, instead of accelerating and slowing down.

In response to Thomas Thorne… It’s a shame that even in speculation about future propulsion technologies it is insinuated that people who entertain novel ideas are invariably labelled crackpot or worse by those who seem to think that there is no new physics to discover. The “defenders of the faith” in the physics community and their groupies forget about the history of science and discovery – namely that by it’s very nature something new will come from a completely unexpected direction to upend prevailing assumptions.

Roger Shawyer’s latest presentation at IAC2014 describes an interstellar probe achieving about 2/3 C in 10 years (Earth time) and covering nearly 4 LY using EMdrive concepts powered by a 200KW nuclear reactor. NASA recently validated the EMdrive/Cannae drive concepts.

http://www.emdrive.com/iac2014presentation.pdf

I’m afraid that NASA has definitely not validated EMdrive/Cannae concepts, despite a recent wave of press to that effect. For a look into this, check here:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=31243

Paul, with all due respect, that article does nothing but suggest that the results cannot be trusted because it appears to offend the standard paradigm. In fact the tone of the article is quite offensive because it belittles legitimate interest and it suggests incompetence on the part of several research teams without evidence. One commentator even suggested that the NASA paper means nothing because the lead author was only a grad student and therefore suspect. There have been eight replications under various circumstances. Hundreds if one includes multiple tests. While further tests are warranted, I have no rational reason to doubt the Chinese team or the NASA replication. What disturbs me even more is that many not only cast doubt without facts but seem genuinely embarrassed by the results.

Of course, no one ever has or ever could violate a true law of physics. Only what we believe is an iron clad law based on our current understanding. What is interesting is that when a conflict arises, there are two approaches, ask what are we missing in our understanding or assume we have a complete knowledge of the matter and thus condemn the results as incompetence or error. It seems to be a trait in science to take the latter approach.

I have to return to the point that NASA has not validated the EM/Cannae drive concept. When you use the word ‘validation,’ you’re implying that the agency now accepts these ideas as proven science, which is not the case. As my article notes:

“…finding a hole in conservation of momentum would be a result so unexpected that we can expect any laboratory producing such results to undergo examination about its methodology. We can also expect papers undergoing peer review that defend the findings.”

We’re only partway into the process.

Just to clarify re the EM-Drive and the Eagleworks tests, the performance claimed by Shawyer and the Chinese was not observed. Also thrust was only observed when a dielectric was placed in the microwave cavity – also contra Shawyer’s theory. Thus, on balance, the EM-Drive needs a lot more work to be claimed to actually work.

Paul,

Yes we are only partway into the process but the tone of many rebuttals articles have not been cautious as much as hostile and filled with ridicule (and in several cases, just wrong on the details). But what constitutes validation of anything? Someone publishes data and someone else publishes a replication.

The NASA paper is part of that process and cannot be disregarded until a seemingly “better” replication comes about. So far there have been about eight sets of data. Who decides what is enough?

Also, as far as I know, one involved is claiming that momentum is not conserved, only the critics are making that strawman claim.

Adam,

You cannot claim both that the NASA work is not a replication and then also use it to cast doubt on the magnitude of the data from the Chinese team and Shawyer.

All tests had different conditions and test configurations yet their have been several replications of thrust. Yes more work is needed but of all places, the folks here should be somewhat excited and hopeful. You state “Also thrust was only observed when a dielectric was placed in the microwave cavity – also contra Shawyer’s theory” which is typical of the modern scientific mindset, you worry more that the data does not seemingly exactly fit with Shawyer’s theory, like that is the most important aspect, while downplaying the glaringly important point- that thrust was observed! The modern mind likes to exalt the theoretical edifice above even experimental data which I believe actually holds progress back. Missing the forest for the trees as they say….

The bottom line is that there now exists several sets of data that suggest that EM/Cannae drives can be built. Folks here should be interested.

Sorry, I meant no one involved is making that claim…..