When I was last in Oak Ridge, TN for the Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop in 2011, I arrived late in the evening and the fog was so thick that, although I had a map, I decided against trying to find Robert Kennedy’s house, where the pre-conference reception was being held. This year the fog held off until the first morning of the conference (it soon burned off even then), and I drove with Al Jackson out to the Kennedy residence, finding the quiet street surrounded by woods still lit with fall colors and the marvelous clean air of the Cumberland foothills.

A house full of interstellar-minded people makes for lively conversation almost anywhere you turn. I quickly met the SETI League’s Paul Shuch, with whom I’ve often corresponded but never spoken to in person, and our talk ranged over SETI’s history, the division into a targeted search and a broader survey (the latter is the SETI League’ bread and butter), and why looking for signals through a very narrow pipe (Arecibo) should only be one out of a spectrum of strategies.

Robert’s 15 cats were largely locked in a room somewhere, but four of them had been allowed to roam, along with a small, inquisitive dog. I spent time at the reception with Marc Millis, with Icarus Interstellar’s Robert Freeland (Andreas Hein was also at the conference, having flown over all the way from Germany, and so was Rob Swinney, who came in from Lincoln in the UK — Rob leads Project Icarus, the ongoing attempt to redesign the original Daedalus starship), and conference organizers David Fields, Les Johnson and Martha Knowles.

John Rather, a tall, friendly man extended a hand, and I suddenly realized this was the John Rather who had done so much to analyze Robert Forward’s sail concepts in the 1970’s, working under a contract with JPL. Later I would see a photo of him with Heinlein and felt the familiar surge of science fictional associations that many scientists bring to this work. I didn’t see Jim Early until the next night, when we had dinner at a table with Jim Benford and Al Jackson, but I have much to say about his paper on sails and the interstellar medium, which showed in 2000 that damage from deep space gas and dust should be minimal. I had covered this paper with Jim’s email help just two years ago and only later put Jim’s face together with the story.

And so it goes at events like this. You meet people with whom you’ve had correspondence and there is a slight mental lock before you put them in the context of the work they have done. I would say that these mental blocks show I’m getting older, but the fact is that I’ve always been slow on the uptake. That’s why I find conferences so valuable, because as soon as I make the needed connections, ideas start to sprout and connect with older materials I’ve written about. In any case, we may benefit here by getting some new material from several TVIW attendees, with whom I discussed writing up concepts from their presentations and the workshop sessions.

Image: TVIW 2014’s reception getting started at Robert Kennedy’s house in Oak Ridge.

Sara Seager: Of Exoplanets and Starshades

“Think about this. People growing up today have always had exoplanets in their lives.” So said Sara Seager, launching the conference after Les Johnson’s introduction on Monday the 10th. Based at MIT, Seager is a major figure in the exoplanet hunt whose work has earned plaudits in the scientific community and also in the popular press. To get to know not just the details of her work but also her character, I’d recommend Lee Billings’ Five Billion Years of Solitude (Current, 2014), which offers a fine look at the scientist and the challenges she has faced in terms of personal loss.

We always talk about habitable zones, Seager reminded the audience, because of our fascination with finding an Earth 2.0. But in fact a habitable zone can be hard to predict, especially when you’re dealing with variable exoplanet atmospheres, a Seager specialty. In fact, exoplanet habitability could be planet-specific.

“You can have planets with denser atmospheres that are much farther from the habitable zone than ours,” Seager said. “Molecular hydrogen is a greenhouse gas. It absorbs continuously across the wavelength spectrum and in some cases could extend the habitable zone out as far as 10 AU. You could also have planets closer to their star than Venus is to the Sun if the planet had less water vapor to begin with, and thus less absorbing power. The boundaries of what we call the habitable zone are controversial.”

Seager has written two textbooks, one of them — Exoplanet Atmospheres: Physical Processes (Princeton University Press, 2010) — specifically on how we characterize such atmospheres. Transmission spectroscopy helps us study a gaseous envelope even when the planet itself cannot be seen, because we’re able to compare the spectra of the star itself when a transiting planet is behind it and again when that same planet begins or exits its transit. Teasing out atmospheric molecules isn’t easy but five exoplanet spectra have been studied in great detail using these methods, and according to Seager, several dozen more have been measured.

The problem here is that transits rely on the fortuitous alignment between planet and star, so that we observe the planet moving across the face of the star. But transits are hugely helpful nonetheless, and given the transit depth, small M-dwarf stars with a ‘super-Earth’ around them would be the easiest to work with — Seager calls these not Earth 2.0 but Earth 2.5. Missions like TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) will home in on the closest 1000 M-dwarfs to look for transits. TESS launches in 2017 and Seager believes we might find such a world by the early 2020’s, a tidally locked planet no more than tens, or hundreds, of light years from our Sun.

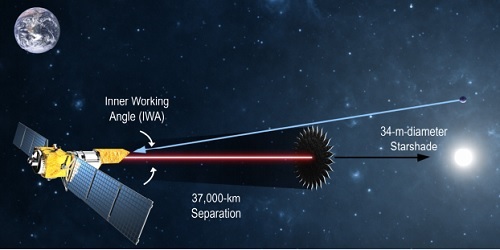

To get around thet transit alignment problem, NASA has long been studying starshade concepts, with a precisely shaped starshade flying tens of thousands of kilometers from a space-based telescope. Using such a configuration, we can start to overcome the problem of glare from the star masking the presence of a planet. Earth is ten billion times fainter than the Sun in visible light, but a properly shaped starshade can reduce the contrast, particularly in the infrared. Can the upcoming Wide-Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), designed for wide-field imaging and spectroscopic surveys of the near-infrared sky, be adapted for starshade capability?

Seager thinks that it can, and gives the idea an 80 percent chance of happening. This will involve a guide camera and communications system for closed loop formation flying. That leaves us with a host of issues including deployment — Seager showed testing on small starshade segments — and propulsion — how do you move the starshade around as you change the alignment between shade and telescope to fix upon a new target? Re-targeting, Seager noted, takes time, and solar-electric propulsion may be one way to handle the propulsion requirement. Centauri Dreams regular Ashley Baldwin, who follows space telescope issues in great detail, will be writing up starshade concepts here in the near future.

Image: Schematic of the starshade-telescope system (not to scale). Starshade viewing geometry with inner working angle (IWA) independent of telescope size. Credit: Exo-S: Starshade Probe-Class Exoplanet Direct Imaging Mission Concept: Interim Report. For more on the most recent work on starshades, including this report, see exep.jpl.nasa.gov/stdt.

The Great Days of 1983

The Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop, now in its third iteration with a fourth planned for 2016 in Chattanooga, is beginning to remind me of a storied conference held in 1983. The Conference on Interstellar Migration was held at Los Alamos in May of that year. It was designed to be multidisciplinary and included practitioners of anthropology, sociology, physics and astronomy as the attendees engaged on issues of emerging technologies, historical migrations, and the future of our species. The proceedings, Interstellar Migration and the Human Experience is a key text for those trying to place our interstellar ambitions in context.

TVIW has always had a bit of the multidisciplinary about it, as we’ll see tomorrow, when I talk about papers not only from the physics perspective (Jim Benford on beamed sail work), but biology (Robert Hampson), biochemistry (Fred Sloop) and anthropology (Sam Lightfoot). This conference did not have as striking a mix among disciplines as the Los Alamos conference, but I’ve appreciated that the organizers have continued to bring in perspectives from a variety of sciences, the result of which is usually a helpful cross-pollination of ideas. We’ll be looking at how some of these played out as this week continues with more of my report from Oak Ridge.

I’d like to know how much more gravity does a planet have to have in order to have a lot of molecular hydrogen. The reason being is that the more distant a planet is from a star the less solar energy is available to propel an atmosphere molecule which is why Titan is so small but has an atmosphere more denser than the Earth yet has a very low escape velocity so it retained most of its atmosphere due to the extreme cold. Put Titan near the Earth and that atmosphere might evaporate away and be lost into space. Mars has lost most of it’s oxygen that way according to Viking orbiter data on it’s atmosphere since it has only an escape velocity of 3.1 miles per second and the Earth 7. My point is 10 au is around where Saturn is and a planet there with a large amount of molecular hydrogen must be a gas giant or at least a mini Neptune and how habitable is that? I’d like to see some Earth like planets with more molecular hydrogen but are there any at that distance? Don’t such bodies usually become gas giants?. Earth in it’s early history might have been different with more molecular hydrogen as the Sun’s brightness was much less than today.

Paul, I am interested in the gas and dust medium issue Jim Benford ‘which showed in 2000 that damage from deep space gas and dust should be minimal’ do you have a pointer to the papers? I find that although gas and dust should not be an issue with a smaller more solid probe it would have serious effects on a thin sail. I would just like to see how he overcome these issues.

Michael, it wasn’t Jim Benford who showed this but Jim Early, in a paper in 2000. The effects are readily managed. You can find the citation within my article on Early’s work from a couple of years ago:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=22534

I’ve been thinking about an Earth like world with molecular hydrogen between 1 and 10 Au. It might be possible to have an Earth like world without a crushing atmospheric pressure like a gas giant depending on how much dust, gas and matter was in the accretion disk around such a planet in an young solar system. The father away from the star the more it might be a cold frozen world like Titan.

It is good to go back to 2012 and revisit our discussion on the effect of interstellar gas on thin metal membranes. It ended with a disagreement between one Florian Marquart and myself on the numbers resulting from an agreed upon formula for the Rutherford cross section for knocking atoms out of the foil. Not a real disagreement, technically, as it seems Florian posted 8 months later, long after I had abandoned the thread.

After redoing the calculation, I happily concede that Florian is correct, and thus most likely so is Jim Early. Together with experimental results I posted earlier on sputtering yields, which also appear to be much lower than I had previously feared, it now seems that we are in the clear with radiation damage to thin light sails. It appears to be negligible.

Eniac, assuming the proton was indeed stripped of its electron without damaging the surface, and didn’t pick up more, then this would imply films of only a few thousand atoms in depth would sustain a thousand times less molecular damage and heating than thicker ones… Interesting if nothing has been missed, such as whether this process causes the sail to become so highly charged that this causes other problems.

Rob, the charging effect is likely minimal, since it does not depend on the energy of the particles, and should be much less in the ISM than for interplanetary sails exposed to the far denser solar wind.