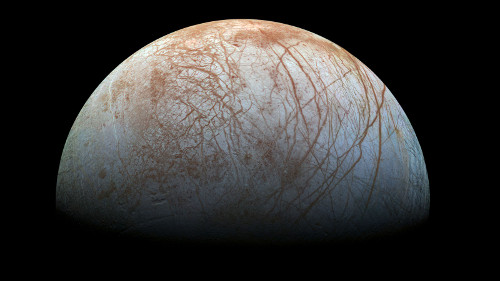

Apropos of yesterday’s post questioning what missions would follow up the current wave of planetary exploration, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory has released a new view of NASA’s intriguing moon Europa. The image, shown below, looks familiar because it was published in 2001, though at lower-resolution and with considerable color enhancement. The new mosaic gives us the largest portion of the moon’s surface at the highest resolution, and without the color enhancement, so that it approximates what the human eye would see.

The mosaic of images that go into this view was put together in the late 1990s using imagery from the Galileo spacecraft, which again makes me thankful for Galileo, a mission that succeeded despite all its high-gain antenna problems, and anxious for renewed data from this moon. The original data for the mosaic were acquired by the Galileo Solid-State Imaging experiment on two different orbits through the system of Jovian moons, the first in 1995, the second in 1998.

NASA is also offering a new video explaining why the interesting fracture features merit investigation, given the evidence for a salty subsurface ocean and the potential for at least simple forms of life within. It’s a vivid reminder of why Europa is a priority target.

Image (click to enlarge): The puzzling, fascinating surface of Jupiter’s icy moon Europa looms large in this newly-reprocessed color view, made from images taken by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft in the late 1990s. This is the color view of Europa from Galileo that shows the largest portion of the moon’s surface at the highest resolution. Credit: NASA/Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Areas that appear blue or white are thought to be relatively pure water ice, with the polar regions (left and right in the image — north is to the right) bluer than the equatorial latitudes, which are more white. This JPL news release notes that the variation is thought to be due to differences in ice grain size in the two areas. The long cracks and ridges on the surface are interrupted by disrupted terrain that indicates broken crust that has re-frozen. Just what do the reddish-brown fractures and markings have to tell us about the chemistry of the Europan ocean, and the possibility of materials cycling between that ocean and the ice shell?

Having been into digital image processing since the early 1980s (and still doing it professionally for scientific applications to this day), I love seeing what can be done today with old data. Still, images like this only whet my appetite for more. I can’t wait for the next mission to study the moons of Jupiter (Juno, which is currently on its way to Jupiter is ill suited to study the moons) and I am anxious to see what comes out of NASA’s current competition. While not in the running (as far as I know), I am rather partial to my Europa sample return concept that would use technology from NASA’s Stardust mission to collect samples from Europa’s polar plume or even the volcanic plumes of Io which was originally proposed here:

http://www.drewexmachina.com/2014/03/27/a-europa-io-sample-return-mission/

With a glowing review from Paul Gilster here

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=30713

Europa (literally) leaves me cold. As there are serious constraints on plutonium for deep space missions, I do not see any priority and going back to Jupiter/Europa. A Cassini class mission to Neptune/Triton would be a much better investment. We know next to nothing about Neptune class planets, which is a huge deficit considering that Neptunes and mini-Neptunes might be the most common type of extrasolar planets. Triton is likely a captured typical KBO. Think how much we could learn about KBOs with a Cassini type probe doing a multi-year study of geological.

Given the current climate of complete Mars obsession and overspending on the part of NASA, I will not get excited about a possible Europa mission until it’s on the launch pad. I remember how concept after concept has been announced and then cancelled (Europa Orbiter, JIMO, JUICE, Laplace) since 1986.

NASA has got the gall of crying poor as one of the reasons for not doing an Europa mission : of course it’s got no money, it spent billion after billion on Mars without any scientific balance.

The funny thing is : the more they spend on Mars, the less habitable it looks. The opposite of Europa.

As far as I’m concerned, the only serious mission planned for Europa is ESA’s two flybys from its Ganymede’s orbiter. Anything else I believe it when I see it.

Sorry, that was 1996, not 1986 when it became clear that an ocean was a serious possibility.