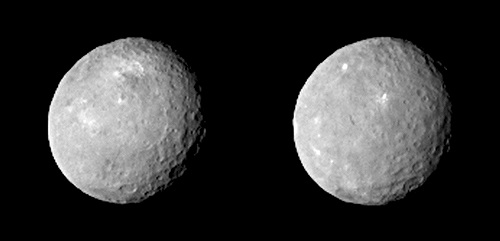

Now it’s really getting interesting. Here are the two views of Ceres that the Dawn spacecraft acquired on February 12. The distance here is about 83,000 kilometers, the images taken ten hours apart and magnified. As has been true each time we’ve talked about Ceres in recent weeks, these views are the best ever attained, with arrival at the dwarf planet slated for March 6.

What I notice and really enjoy about watching Dawn in action is the pace of the encounter. Dawn is currently moving at a speed of 0.08 kilometers per second relative to Ceres, which works out to 288 kilometers per hour. The distance of 83,000 kilometers on the 12th of February has now closed (as of 1325 UTC today, the 18th) to 50,330 kilometers. Its quite a change of pace from the days when we used to watch Voyager homing in on a planetary encounter. Voyager 2 reached about 34 kilometers per second as it approached Saturn, for example, then slowed dramatically as it climbed out of the giant planet’s gravitational well. The same profile held with each encounter.

Have a look at this JPL graph of Voyager 2 assist velocity changes and you’ll see the profile for each planetary flyby. In each case, the spacecraft comes into the gravitational influence of the planet and falls towards it, increasing its speed to a maximum at the time of closest approach. The numbers at closest approach to Saturn are actually over twice what Voyager 2 is making right now — 15.4 kilometers per second — but it’s the climb out of the gravity well that slows the vehicle down, something that is clearly shown in the graph at each encounter. Voyager 2, as noted below, actually left the Earth moving at 36 kilometers per second relative to the Sun.

Image: Voyager 2 leaves Earth at about 36 km/s relative to the sun. Climbing out, it loses much of the initial velocity the launch vehicle provided. Nearing Jupiter, its speed is increased by the planet’s gravity, and the spacecraft’s velocity exceeds Solar System escape velocity. Voyager departs Jupiter with more sun-relative velocity than it had on arrival. The same is seen at Saturn and Uranus. The Neptune flyby was designed to put Voyager close by Neptune’s moon Triton rather than to attain more speed. Diagram courtesy Steve Matousek, JPL.

The result for those of us watching spellbound as the Voyager mission progressed was that the planetary flybys were over quickly, the newly seen planetary details and moons captured for later analysis. With the benefit of supple ion propulsion, Dawn approaches at a far more leisurely pace as it moves toward not flyby but orbit around its latest target. To judge from what we’re seeing in the latest imagery, Ceres is going to be a fascinating place to explore. Note the craters and bright spots that have people talking throughout the space community.

“As we slowly approach the stage, our eyes transfixed on Ceres and her planetary dance, we find she has beguiled us but left us none the wiser,” said Chris Russell, principal investigator of the Dawn mission, based at UCLA. “We expected to be surprised; we did not expect to be this puzzled.”

Given how much we learned about Vesta during Dawn’s fourteen month exploration of the asteroid, we can hope that a comparative analysis of Ceres will teach us much about the formation of these objects and the Solar System itself. The best resolution in the images above is 7.8 kilometers per pixel. But day by day a small world is opening up, slowly, majestically. We may be looking at a place that becomes a significant resource for an expanding interplanetary economy in some much to be hoped for future. I’m reminded of a work by the Irish poet Eavan Boland, drawn back to it this morning because of the title: ‘Ceres Looks at the Morning.’ Boland’s reference is to the classical goddess Ceres, but this excerpt seems apropos as we approach and reveal a new land:

Beautiful morning

look at me as a daughter would

look: with that love and that curiosity:

as to what she came from.

And what she will become.

I never realized that the Neptune flyby was the only one that did not provide a gravity boost to Voyager 2.

The right image of Ceres seems to show a crater with a white (ice?) interior and icy ejecta around it. The left image seems to show a peak inside what may be a very large crater. It will be interesting to see these in much more detail, as well as a host of features as the resolution improves.

It is starting to look like mini moon, now is that a large relaxed impact basin in the centre or are my eyes playing tricks on me.

While I am, like everyone else, looking forward to Dawn’s arrival and research in orbit around Ceres; I do have one question. I am wondering out loud as to if Dawn has enough fuel and is in good enough condition to make it to yet another asteroid ? As fantastic as this has been it would even more so if it could do a threesome!!! I am NOT an expert in orbital dynamics to judge or even guess what additional target or targets might be possible. I know this jumping the gun, but it is interesting to think about.

Off topic, John Baez had a nice writeup of running combined ice – atmosphere – sea (Community Climate System Model 3.0) models on tidally locked red dwarf planets on his blog a few days back. Turns out it’s not so clear cut whether all the water gets trapped to the dark side, or not, it depends on… check it out!

https://johncarlosbaez.wordpress.com/2015/02/14/earth-like-planets-near-red-dwarfs/

The paper he was talking about:

http://arxiv.org/abs/1411.0540

Correct me if I’m wrong, but a spacecraft gravitational assist boost does not utilize the planets gravity (it falls in, gains velocity V and climbs out, losing velocity V); rather (to gain velocity) it is aimed slightly behind the planet as it orbits the sun and steals a tiny bit of the planets angular momentum, right?

Ceres’ rotation rate was precicely known PRIOR to the Dawn mission, but its axial tilt was much less defined. With the time-lapsed immages coming in, that data should now be as precice as the rotation rate data. Does anyone know what it is. This is important to the mission because once Dwan is in its final polar orbit configuration, this new data will affect the amount of time it will take to achieve 100% imaging of the dwarf planet.

Tom,

There was originally talk of Dawn doing a post-Ceres flyby of Pallas. That would have been awesome but she’s lost 2 reaction wheels and its going to take some good luck and management to complete the Ceres work if another one goes soon. So no, Dawn wont be going anywhere once it enters orbit.

P

@P @Tom: As I read on the Dawn blog and other sources, once Dawn is out of hydrazine (used for orientating, compensating the lost reaction wheels) it will be a permanent satellite of Ceres! Perhaps Dawn & New Horizons will usher a new era of exploration! Countless worlds await!

Paul, do you or anyone reading this post have access to the Time-Life Nature Series of books from the early 1960s, namely the one titled The Universe? I distinctly recall an artist’s depiction of Ceres and several other known large planetoids with Texas in the background for a size comparison.

The best part is I recall that Ceres was shown as a crater-covered sphere, pretty much what we are seeing now, though I think the craters in the artwork were larger. Can someone scan in that piece and post it here? It might also be interesting to see how other artists depicted Ceres over the ages as Dawn arrives to reveal the planetoid’s real surface. Thank you.

I don’t have this, I’m afraid, but perhaps one of the other readers will.

Eric, yes a flyby borrows angular velocity, but both from the planets rotation AND the planets angular velocity of orbiting around the sun, but it is the gravity of the planet that makes this possible just as a sling still needs a string to work…

.

EricSECT, that’s a weird way to put it. Here is the way I would state it.

This falling down the gravitational well and picking up speed wrt the planet is a distraction. The ONLY relevance here is the way the direction, but not magnitude of the vector, is changed wrt the planet AND that the planet is moving wrt the star. Think about this with anything you know (say cars replacing planets and a lamppost replacing Sol) and after a few moments you will see how speed can be gained wrt sol (the lamppost)

Clue: I am in a red car heading towards a blue and both are traveling at 100 kmph. I am allowed to swing around it and travel in its direction, yet the rules state our velocity difference must still remain 200 kmph. It is a big Kenworth so its speed wont change, which means I must end up traveling at 300 kmph wrt any lamppost.

This comment is less directed at your post on Ceres than intended as a suggestion for a future Centauri Dreams post on the definition of a planet. I have never been comfortable with the current definition because it seems much too directed at getting the desired answer rather than developing a classification that is universally applicable.

Scientific definitions are ideally based on fundamental physics (or chemistry etc) and are characterized by simplicity. In the case of a planet, it seems to me that there are a few scientifically justifiable “break points”. Experts may be able to refine my selection, but let me suggest, in order of increasing mass: (i) hydrostatic equilibrium, (ii) development of an extensive atmosphere, (iii) formation of a degenerate core and (iv) initiation of nuclear fusion.

I would like to define a planet as any object lying between hydrostatic equilibrium and nuclear fusion. By this definition, the Moon is a planet. We peel off the Moon and other such objects by saying that a “moon” is a “planet” orbiting a larger planet such that the center of gravity lies inside the larger planet. Pluto/Charon is then a “double planet”.

Break point (ii) seems, from Kepler data, to lie at about 1.6 Earth radii. We could use it to separate “rocky planets” and “gas planets”, but I would call both “planets”. For the moment, I see no real use for break point (iii) (formation of a degenerate core) but it is nevertheless a structural change that is (roughly) identifiable from radius and mass data, and might find future use.

This suggestion includes objects around other stars as well as the so-called “rogue planets” unattached to any star. It also gives the solar system quite a few extra planets, but I see little problem in that. Our solar system probably does have 15-20 large, round objects out there and any attempt to call some planets and others non-planets seems to me to be based more on emotion rather than physics.

Simplicity is usually a virtue and I would really like to avoid criteria such as “clears nearby orbits” and “greater than or equal to the mass of Pluto” because they are either not generally applicable (i.e. for other stars) or artificial and scientifically meaningless.

Norm Davison: I think the correct term is “binary planet” instead of “double planet”. It is interesting you bring this up, due to the POSSIBLE detection of an exomoon around Kepler 264b. Should the current OSE evidence hold up (I’m sure Kipping et al is analysing the available data with the PLEIDES supercomputer RIGHT NOW), and the parameters remain the same, a 1.6 Re object orbiting a 3.3 Re object at a distance of 31 X 3.3 Re would HAVE to be the “B” component of a binary planet system instesd of an exomoon (its OFFICIAL designatiom would be Kepler 264f, abd the binary planet would be probably known a Kepler 264bf). BACK TO CERES: The siderial rotation period IS very precice (as I stated in my earlier comment), ie 9.07417 hours, but the axial tilt is listed in Wikipedia as 3 degrees. Looking at the ASCENCION of the “white spot” I am inclined to believe that it is more like 10 degrees.

Closer and sharper with each passing hour:

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=4491

How spherical is Ceres? I’ve added a circle to the image above. Note that there is a depression in the upper left quadrant of both views, and a larger depression in the lower left quadrant of the view on the left. Does this say anything about the history or composition of this body?

Ceres images with circle overlay

Dawn Journal: Ceres’ Deepening Mysteries

Posted by Marc Rayman

2015/02/25 20:00 UTC

Dear Fine and Dawndy Readers,

The Dawn spacecraft is performing flawlessly as it conducts the first exploration of the first dwarf planet. Each new picture of Ceres reveals exciting and surprising new details about a fascinating and enigmatic orb that has been glimpsed only as a smudge of light for more than two centuries. And yet as that fuzzy little blob comes into sharper focus, it seems to grow only more perplexing.

Dawn is showing us exotic scenery on a world that dates back to the dawn of the solar system, more than 4.5 billion years ago. Craters large and small remind us that Ceres lives in the rough and tumble environment of the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and collectively they will help scientists develop a deeper understanding of the history and nature not only of Ceres itself but also of the solar system.

Even as we discover more about Ceres, some mysteries only deepen. It certainly does not require sophisticated scientific insight to be captivated by the bright spots. What are they? At this point, the clearest answer is that the answer is unknown. One of the great rewards of exploring the cosmos is uncovering new questions, and this one captures the imagination of everyone who gazes at the pictures sent back from deep space.

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/marc-rayman/0225-dawn-journal-ceres-deepening-mysteries.html

At last, Ceres is a geological world

Posted by Emily Lakdawalla

2015/02/26 03:42 UTC

I’ve been resisting all urges to speculate on what kinds of geological features are present on Ceres, until now. Finally, Dawn has gotten close enough that the pictures it has returned show geology. Before, we could clearly see craters; but everything has craters. Now, with the latest images taken on February 19, we can see the shapes of those craters, and begin to interpret what they mean about Ceres’ interior and geologic history.

But we shouldn’t get carried away, because the images still have a pretty small number of pixels; at their original resolution, the visible disk is about 210 pixels wide.

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2015/02251857-ceres-geology.html

Alex Tolley: As I mentioned in a comment posted on an earlier blog regarding Ceres, it is DEFINATELY NOT PERFECTLY CIRCULAR, and not even NEARLY circular. Like Saturn, Ceres exhibits symmetrical OBLATENESS ( the equitorial to polar radii ratios derived from Wikipedia data are as follows: Saturn; 1.1086012: Ceres; 1.0716956). I strongly suspect, that after wery detailed images come in, the ratio for Ceres MAY INCREASE SOMEWHAT, making it almost identical to Saturn’s. S[peaking of more detailed images, the above mentioned February batch had apparently resolved the “mysterious white spot” into TWO DISTINCT SPOTS separated by a small area of the standard dark surface about the same size as the two spots. Far more interesting is that the larger and brighter of the two white spots is located exactly in the center of either a large ancient degraded (volcanic!?) crater, or a rather small impact basin.

@Harry – what I wanted to show was the apparent “flatness” of the craters in the areas I identified. I wondered if this suggested that any subsurface ocean would have to be well below the surface. It turns our that ljk’s reference for Emily Lakdawalla’s piece explained it very well – major craters that may have flooded with subsurface material.

While I well understand that Ceres is oblate, this is far less a deviation than the crudely observed “depressions” that a simple fitted circle highlights.

Looking forward to higher res images of those bright points. Maybe they are volcanic. It might possibly explain that faint water vapor signature found around Ceres by Herschel last year.