When it comes to Saturn, have you noticed what’s been missing lately? Well, actually for the last two years. While the Cassini orbiter has had high-profile encounters with Titan, it has been in a high-inclination orbit that has meant no recent flybys of other Saturnian moons. All that has now changed as Cassini returned to the planet’s equatorial plane this month, which means we can look forward to more interesting views like these mosaics of the planet’s second largest moon Rhea.

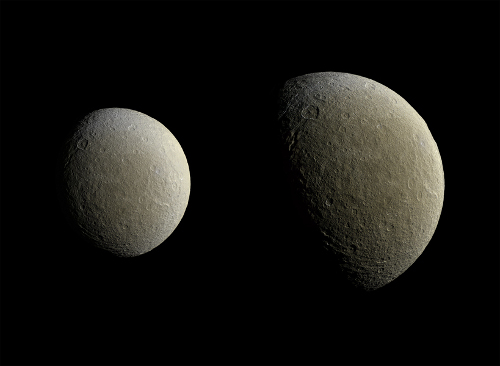

Image: Two mosaics of Saturn’s icy moon Rhea, with constituent images taken about an hour and a half apart on February 9, 2015. Images taken using clear, green, infrared and ultraviolet spectral filters were combined to create these enhanced color views, which offer an expanded range of the colors visible to human eyes in order to highlight subtle color differences across Rhea’s surface. The moon’s surface is fairly uniform in natural color. Credit: JPL.

The Rhea imagery comes from a flyby of the moon on February 9, the first encounter other than Titan since early 2013. Resolution in the smaller mosaic is 450 meters per pixel, while the view on the right has a resolution of 300 meters per pixel. The images going into the mosaic on the right were acquired at a distance that ranged from 57,900 kilometers to 51,700 kilometers; those on the left from distances between 82,100 to 74,600 kilometers. Each mosaic is made up of multiple narrow-angle camera (NAC) images, with wide-angle camera data used where necessary to fill in the areas where the NAC data were not available.

Rhea is the ninth largest moon in the Solar System, and while it doesn’t turn up very often in discussions of astrobiology, I should note a 2006 paper from Hauke Hussmann (Universidade de São Paulo) and colleagues that investigates the possibility of sub-surface oceans in the medium-sized icy satellites as well as the largest trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs). The paper argues that assuming differentiation and an equilibrium between heat production in the rocky cores and heat loss through the ice shell, sub-surface oceans are possible on Rhea, Titania, Oberon, Triton, and Pluto and on the large TNO’s Eris, Sedna, and Orcus (2004 DW).

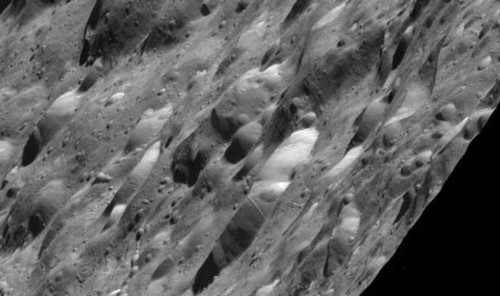

Image: Cassini’s wide-angle camera took this image of Rhea from about 200 kilometers away from the moon’s surface in early 2011. Credit: JPL.

Back in 2011, Cassini completed a close flyby of Rhea, with closest approach achieved on January 11 of that year. The imagery above shows an old, cratered and apparently inert surface, with some evidence of straight faults that show up better in other Rhea imagery. Further study of Rhea via Cassini will help us determine how its extremely tenuous atmosphere of oxygen and CO2 interacts with particles in Saturn’s magnetosphere.

Next up for Cassini in its new, nearly equatorial orbit: A May 7 flyby of Titan, the first of four in 2015, as well as two encounters with Dione and three with the always interesting Enceladus. The Hussmann paper mentioned above is “Subsurface oceans and deep interiors of medium-sized outer planet satellites and large trans-neptunian objects,” Icarus Volume 185, Issue 1 (November 2006), pp. 258-273 (abstract).

These kind of results from the Cassini mission really show what a loss Galileo’s high-gain antenna was. Time to return to Jupiter. (And Uranus and Neptune for that matter, but I guess I won’t be around to see that, if it ever happens…)

Are you aware of any further study of the magnetic/plasma anomalies associated with Rhea (the ones that led to the ring system conjecture)?

andy, no, but I’ve decided to look into this. I’ll report back if I come up with something interesting.

Uranus and/or Neptune is a must. It’s criminal no mission is in the offing given it is known that these type of planet, in different sizes, are ubiquitous in the galaxy. So much to learn from them . Maybe the availability of the cheap Falcon Heavy in conjunction with the NEXT ion propulsion system will allow the shortened direct flights that will save on expensive mission operation and engineering costs . This in conjunction with the availability of cheap compact spectrographs , lightweight construction materials like silicon carbide and nano satellites might just bring the mission cost within the $1 billion New Frontiers cost bracket.

I was surprised when Landis pointed out that there are altitudes in Venus’ atmosphere where pressure and temperature were hospitable to humans.

I am wondering if the same is true of many of the larger icey bodies in our solar system. Instead of floating cloud cities, humans could live in subsurface bubbles within these oceans. Maybe there are comfortable potential homes even out in the Oort!

I have long daydreamed of subsurface oceans on the icey moons of our gas giants. But the notion of liquid water on TNOs is a new one. I can hardly wait for the fly by of Pluto and Charon this July.