‘Europa in a can’ may be the clue to what’s happening on Jupiter’s most intriguing moon. Created by JPL’s Kevin Hand and Robert Carlson, ‘Europa in a can’ is the nickname for a laboratory setup that mimics conditions on the surface of Europa. It’s a micro-environment of extremes, as you would imagine. The temperature in the vacuum chamber is minus 173 degrees Celsius. Moreover, materials within are bombarded with an electron beam that simulates the effects of Jupiter’s magnetic field. Ions and electrons strike Europa in a constant bath of radiation.

What Hand and Carlson are trying to understand is the nature of the dark material that coats Europa’s long fractures and much of the other terrain that is thought to be geologically young. The association with younger terrain would implicate materials that have welled up from within the moon, providing an interesting glimpse of what is assumed to be Europa’s ocean. Previous studies have suggested that these discolorations could be attributed to sulfur and magnesium compounds, but Hand and Carlson have produced a new candidate: Sea salt.

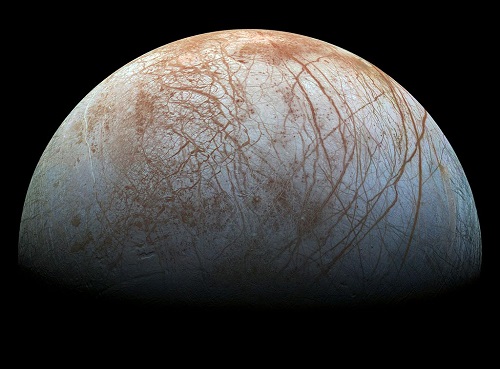

Image: The Galileo spacecraft gave us our best views thus far of Europa, with the discolorations along linear fractures rendered strikingly clear in this reprocessed color view. Credit: NASA/JPL.

Intense radiation peppers Europa’s surface with particle accelerator intensity. It becomes part of the story, causing the discoloration evident in the terrain. Hand and Carlson tested a variety of candidate substances, collecting the spectra of each to compare them with what our spacecraft and telescopes have found. Sodium chloride and various salt and water mixtures proved the most potent substance. When bombarded with the electron beam, they turned from white to the same reddish brown hues found on Europa in a timeframe of tens of hours, which corresponds to about a century on Europa. Spectral measurements showed a strong resemblance to the color within Europa’s fractures as seen by the Galileo spacecraft.

Image: A closer look at Europa. This is a colorized image pulled from clear-filter grayscale data from one orbit of the Galileo spacecraft combined with lower resolution data taken on a different orbit. The blue-white terrain indicates relatively pure water ice. The new work indicates that although some of the colors of Europa come from radiation-processed sulfur, irradiated salts may explain the color of the youngest regions. Highly intriguing is the possibility that these surface features may have communicated with a global subsurface ocean. Credit: NASA/JPL.

Finding sea salt on Europa’s surface would imply interactions between the ocean and the rocky seafloor, according to this JPL news release, with astrobiological implications. In any case, “This work tells us the chemical signature of radiation-baked sodium chloride is a compelling match to spacecraft data for Europa’s mystery material,” says Hand, who speculates that because the samples grew darker with increasing radiation exposure, we might be able to use color variation to determine the age of features on the moon’s surface.

The paper is Hand and Carlson, “Europa’s surface color suggests an ocean rich with sodium chloride,” accepted at Geophysical Research Letters for publication online (abstract).

Could it just be rust, iron oxide, that has formed in the ocean and upwelled from below due to its interaction with the iron rich core/mantle? If so there is plenty of material available to power primitive life. Our oceans would have looked this colour many billions of years ago.

are spectrometers from orbit precise enough to tell us what it is?

to me that would be the #1 priority for the next europa mission.

#2: mapping thickness of the ice crust so as to determine where we can land in the future and insert the melting probe.

2 years ago Dr. Hand said this:

“A strong candidate for the upwelling substance is magnesium chloride, which doesn’t have a definitive spectral signature and so would be invisible on the surface.”

src: http://www.newscientist.com/article/dn23246-salty-water-oozes-up-from-jupiter-moons-hidden-ocean.html

Science marches on. I haven’t been able to read the paper, but I assume the team ruled out other salts that were previ9ously believed to be the cause of the reddish material.

Last I heard the ‘thick ice’ model for Europa was in favour – doesn’t the thick ice model say the ocean doesn’t have any contact with the surface?

These regions should still be checked for the remains of Europan kelp, jellyfish, and who knows what else?

Richard Greenberg and others would definitely disagree about that thick ice theory:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=17515

The House budget for NASA plants the seeds of a program to finally find life in the outer solar system

Posted on May 19, 2015 | By Eric Berger

On Wednesday the U.S. House Appropriations Committee will “mark up” its 2016 budget proposal for NASA, and much of the attention will focus on cuts to the agency’s Earth science budget and not fully funding the President’s commercial crew program.

Both of those are important issues and worthy of discussion. But I want to call attention to an exciting development buried within the 108-page budget document.

That is the creation of an “Ocean Worlds Exploration Program.”

Many of NASA’s most exciting discoveries in recent years have been made during the robotic exploration of the outer planets. The Cassini mission has discovered vast oceans of liquid hydrocarbons on Saturn’s moon Titan and a submerged salt water sea on Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

The Committee directs NASA to create an Ocean World Exploration Program whose primary goal is to discover extant life on another world using a mix of Discovery, New Frontiers and flagship class missions consistent with the recommendations of current and future Planetary Decadal surveys.

The bill provides $140 million to continue development of a Europa mission, including a lander, and then tacks on an additional $86 million to begin developing plans and technology for forays to other worlds. The principal targets are two exotic moons of Saturn, Titan and Enceladus.

Full article here:

http://blog.chron.com/sciguy/2015/05/the-house-budget-for-nasa-plants-the-seeds-of-a-program-to-finally-find-life-in-the-outer-solar-system/

Here is an interseting article on Europa’s potential stain materials.

http://people.virginia.edu/~rej/papers08/Europa-Chapter3.pdf

May 26, 2015

15-104

NASA’s Europa Mission Begins with Selection of Science Instruments

NASA has selected nine science instruments for a mission to Jupiter’s moon Europa, to investigate whether the mysterious icy moon could harbor conditions suitable for life.

NASA’s Galileo mission yielded strong evidence that Europa, about the size of Earth’s moon, has an ocean beneath a frozen crust of unknown thickness. If proven to exist, this global ocean could have more than twice as much water as Earth. With abundant salt water, a rocky sea floor, and the energy and chemistry provided by tidal heating, Europa could be the best place in the solar system to look for present day life beyond our home planet.

“Europa has tantalized us with its enigmatic icy surface and evidence of a vast ocean, following the amazing data from 11 flybys of the Galileo spacecraft over a decade ago and recent Hubble observations suggesting plumes of water shooting out from the moon,” said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “We’re excited about the potential of this new mission and these instruments to unravel the mysteries of Europa in our quest to find evidence of life beyond Earth.”

NASA’s fiscal year 2016 budget request includes $30 million to formulate a mission to Europa. The mission would send a solar-powered spacecraft into a long, looping orbit around the gas giant Jupiter to perform repeated close flybys of Europa over a three-year period. In total, the mission would perform 45 flybys at altitudes ranging from 16 miles to 1,700 miles (25 kilometers to 2,700 kilometers).

Full article here:

https://www.nasa.gov/press-release/nasa-s-europa-mission-begins-with-selection-of-science-instruments

Why We Don’t Know When the Europa Mission Will Launch

Posted by Casey Dreier

2015/05/27 18:32 UTC

During the recent press conference announcing the scientific instrument package on the upcoming Europa mission, NASA’s Planetary Science Division Director Jim Green was asked when the mission would be ready to launch.

“We expect it to be launched in the 2020s…whether it’s mid, or a little early or a little later, needs to be worked out based on a much firmer cost estimate and a profile that would support it,” said Green.

If this answer seems heavily hedged, it is. The reason is not orbital mechanics. It’s that the Europa mission is currently caught up in a fight over funding priorities between the White House and Congress: powerful members of Congress want the mission to happen sooner; the White House would rather support other programs within NASA.

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/casey-dreier/2015/0527-why-we-dont-know-when-the-europa-mission-will-launch.html

To quote:

After years of false starts, canceled missions, and preliminary studies, the White House agreed to start a new mission to Europa in this year’s budget request for NASA. However, it proposed to spend a relatively small amount of money over the next five years to begin formulating the mission, starting with $30 million in 2016. This funding level is too little to support a launch in the early 2020s, and perhaps even the mid-2020s.

The House of Representatives, meanwhile, has aggressively supported a major mission to Europa, supplying hundreds of millions of dollars over the past few years despite the lack of official NASA requests for this funding. Just a few weeks ago, the House proposed a NASA spending bill for 2016 that would provide the Europa mission with $140 million—$110 million over the requested amount—and dictates NASA to plan to launch the mission in 2022 on the Space Launch System heavy rocket now under development.

What price Europa?

by Jeff Foust

Monday, June 1, 2015

It’s a good time to be involved with, or simply a fan of, a mission to Jupiter’s moon Europa. Last week, NASA announced the selection of a suite of nine instruments that will fly on a mission there the agency plans to launch in the 2020s. Later this week, the House of Representatives is expected to approve a spending bill for fiscal year 2016 that will provide $140 million for that mission, far above what NASA asked for in its budget request.

So, what’s not to like? In the zero-sum game of NASA budget politics, a gain for Europa is a loss for other programs, particularly Earth science. The Europa mission has a powerful champion in a key House member, but his desire to search for life on Europa and other icy worlds of the outer solar system might well end up alienating other scientists.

Full article here:

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/2763/1

To quote:

In that story, Culberson appears more enthusiastic about a Europa mission than even those at JPL working on it. “Where’s the magnetometer?” he asked at one point in the discussion, according to the article. “You’ve got to have a magnetometer.” It’s hard to imagine any other member of Congress getting that involved in the details of a spacecraft mission design—or, for that matter, even knowing what a magnetometer is and why it would be useful at Europa.

At the JPL meeting, Culberson is seen pushing to include a lander of some kind on the Europa Clipper mission. The JPL team there, including Adam Steltzner, who led the development of the Curiosity Mars rover’s landing system, said a small lander could be done for an additional billion dollars.

While some scientists supported an impactor probe that would be simpler and less expensive to build, Culberson instead advocated for a soft lander, one equipped with tools to scoop up samples and analyze them, including a microscope. “Why go all that way if you’re not going to answer the most important question?” Culberson asks in the Chronicle article.

NASA Goes First Class for Europa

Posted by Van Kane

2015/06/10 17:07 UTC

There’s an old saying that the clothes make the man. In planetary exploration, the instrument suite makes the mission. Fewer and simpler instruments can enable a lower cost mission but at the cost of restricting the richness of the scientific investigations.

Jupiter’s moon Europa has been a priority to explore because there’s good evidence that its vast ocean, hidden beneath an icy crust, may have the conditions needed to enable life. However, NASA’s managers have struggled to define a mission that is both compelling and affordable.

Over the last several years, engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) have rethought the entire approach to exploring Europa. They started with a bare bones list of just three must have instruments (with a longer list of optional desired instruments).

Their breakthrough was to plan a mission that would orbit Jupiter and make many brief swoops past Europa before swinging back out of the high radiation zone. NASA now has a concept that’s affordable.

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/van-kane/0610-nasa-goes-first-class-for-europa.html

To quote:

The next key question for NASA’s Europa mission will be when it will launch. JPL’s design team are working towards a 2022 launch, provided the money can be found. The funding is the rub, though. While Congress has pushed for an early flight and backed that with generous funding, only this year has the President’s Office of Management and Budget, which sets the administration’s budget policy, agreed to make a trip to Europa an official NASA program and proposed a tiny down payment towards the mission’s cost.

However, they and NASA’s managers, who ultimately work for the President and must publicly support the administration’s position, only speak vaguely of a launch in the mid-2020s or possibly later. (This reminds me of the father who tells his children that, yes, absolutely we will go to Disneyland someday (and means it), to get them to stop pestering him about the trip now.) The issue is that an earlier flight means either increasing NASA’s budget to pay for the mission or trading it for other work that is on NASA’s plate. (See these good background pieces by Casey Drier at the Planetary Society and Jeff Foust at the Space Review. I’ve also written about this.)

June 17, 2015

15-130

All Systems Go for NASA’s Mission to Jupiter Moon Europa

Beyond Earth, Jupiter’s moon Europa is considered one of the most promising places in the solar system to search for signs of present-day life, and a new NASA mission to explore this potential is moving forward from concept review to development.

NASA’s mission concept — to conduct a detailed survey of Europa and investigate its habitability — has successfully completed its first major review by the agency and now is entering the development phase known as formulation.

“Today we’re taking an exciting step from concept to mission, in our quest to find signs of life beyond Earth,” said John Grunsfeld, associate administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. “Observations of Europa have provided us with tantalizing clues over the last two decades, and the time has come to seek answers to one of humanity’s most profound questions.”

NASA’s Galileo mission to Jupiter in the late 1990s produced strong evidence that Europa, about the size of Earth’s moon, has an ocean beneath its frozen crust. If proven to exist, this global ocean could hold more than twice as much water as Earth. With abundant salt water, a rocky sea floor, and the energy and chemistry provided by tidal heating, Europa may have the ingredients needed to support simple organisms.

The mission plan calls for a spacecraft to be launched to Jupiter in the 2020s, arriving in the distant planet’s orbit after a journey of several years. The spacecraft would orbit the giant planet about every two weeks, providing many opportunities for close flybys of Europa. The mission plan includes 45 flybys, during which the spacecraft would image the moon’s icy surface at high resolution and investigate its composition and the structure of its interior and icy shell.

Full article and video here:

http://www.nasa.gov/press-release/all-systems-go-for-nasas-mission-to-jupiter-moon-europa

How NASA Could Explore Jupiter Moon Europa’s Ocean

Elizabeth Howell, Discovery News | June 23, 2015 07:00 am ET

Europa is an ice-covered moon orbiting Jupiter that likely hosts an undergound ocean. Perhaps that ocean contains life. Perhaps it doesn’t. But we’re not going to know for sure until we send a probe there to check things out.

NASA announced last week that it’s one step closer to flying by Europa dozens of times after launching in the 2020s. The mission concept was approved and funding is ongoing. To get under that ice (virtually), NASA could include a radar instrument called REASON(Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surfaces). But what if we were to eventually send a robotic landing mission?

Britney Schmitt, a member of the Europa mission team, told a conference last week that her team in Antarctica is testing out the very techniques that could be used at Europa, hundreds of millions of kilometers away.

“Europa may seem alien to you and I, but if you go the Earth’s poles, it doesn’t seem as far-fetched,” said Schmidt, who is an assistant professor in the Georgia Institute of Technology’s Earth and atmospheric sciences department.

Full article here:

http://www.space.com/29732-jupiter-moon-europa-ocean-submarine.html

The Beckoning of the Ice Worlds

We’ve been looking for life on Earth-like planets. Will Europa teach us better?

BY COREY S. POWELL

JUNE 25, 2015

Full article here:

http://nautil.us/issue/25/water/the-beckoning-of-the-ice-worlds

Can Elon Musk get us to Europa?

http://www.techinsider.io/elon-musk-spacex-falcon-heavy-europa-mission-2015-9