I had no idea when the week began that I would be ending it with a third consecutive post on Dysonian SETI, but the recent paper on KIC 8462852 by Tabetha Boyajian and colleagues has forced the issue. My original plan for today was to focus in on Cassini’s work at Enceladus, not only because of the high quality of the imagery but the fact that we’re nearing the end of Cassini’s great run investigating Saturn’s icy moons. Then last night I received Jason Wright’s new paper (thanks Brian McConnell!) and there was more to say about KIC 8462852.

Actually, I’m going to look at Wright’s paper in stages. It was late enough last night that I began reading it that I don’t want to rush a paper that covers a broad discussion of megastructures around other stars and how their particular orbits and properties would make them stand out from exoplanets. But the material in the paper on KIC 8462852 certainly follows up our discussion of the last two days, so I’ll focus on that alone this morning. Next week there will be no Centauri Dreams posts as I take a much needed vacation, but when I return (on October 26), I plan to go through the rest of the Wright paper in closer detail.

A professor of astronomy and astrophysics at Penn State, Wright heads up the Glimpsing Heat from Alien Technologies project that looks for the passive signs of an extraterrestrial civilization rather than direct communications, so the study of large objects around other stars is a natural fit (see Glimpsing Heat from Alien Technologies for background). Luc Arnold suggested in 2005 that large objects could be used as a kind of beacon, announcing a civilization’s presence, but it seems more likely that large collectors of light would be deployed first and foremost as energy collectors. We’ve also seen in these pages that a number of searches have been mounted for the infrared signatures of Dyson spheres and other anomalous objects (see, for example, An Archaeological Approach to SETI).

In the last two days we’ve seen why KIC 8462852 is causing so much interest among the SETI community. The possibility that we are looking at the breakup of a large comet or, indeed, an influx of comets caused by a nearby M-dwarf, is thoroughly discussed in the Boyajian paper. This would be a fascinating find in itself, for we’ve never seen anything quite like it. Indeed, among Kepler’s 156,000 stars, there are no other transiting events that mimic the changes in flux we see around this star. Boyajian and team were also able to confirm that the striking dips in the KIC 8462852 light curve were not the result of instrument-related flaws in the data.

So with an astrophysical origin established, it’s interesting to note that Boyajian’s search of the Kepler dataset produced over 1000 objects with a drop in flux of more than ten percent lasting 1.5 hours or more, with no requirement of periodicity. When the researchers studied them in depth, they found that in every case but one — KIC 8462852 — they were dealing with eclipsing binaries as well as stars with numerous starspots. The object remains unique.

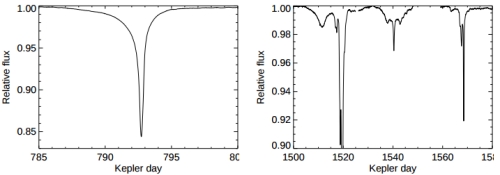

Wright provides an excellent summary of the Boyajian et al. investigations. The Kepler instrument is designed to look for dips in the light curve of a star as it searches for planets. If the frequent dips we see at KIC 8462852 are indeed transits, then we must be looking at quite a few objects. Moreover, the very lack of repetition of the events indicates that we are dealing with objects on long-period orbits. One of the events shows a 22 percent reduction in flux, which Wright points out implies a size around half of the stellar radius (larger if the occulter is not completely opaque). The objects are, as far as we can tell, not spherically symmetric.

Let me quote Wright directly as we proceed:

The complexity of the light curves provide additional constraints: for a star with a uniformly illuminated disk and an occulter with constant shape, the shape of the occulter determines the magnitude of the slope during ingress or egress, but not its sign: a positive slope can only be accomplished by material during third and fourth contact, or by material changing direction multiple times mid-transit (as, for instance, a moon might). The light curves of KIC 8462 clearly show multiple reversals… indicating some material is undergoing egress prior to other material experiencing ingress during a single“event”. This implies either occulters with star-sized gaps, multiple, overlapping transit events, or complex non-Keplerian motion.

Image: Left: a deep, isolated, asymmetric event in the Kepler data for KIC 8462. The deepest portion of the event is a couple of days long, but the long “tails” extend for over 10 days. Right: a complex series of events. The deepest event extends below 0.8, off the bottom of the figure. After Figure 1 of Boyajian et al. (2015). Credit: Wright et al.

A giant ring system? It’s a tempting thought, but the dips in light do not occur symmetrically in time, and as Wright points out, we don’t have an excess at infrared wavelengths that would be consistent with rings or debris disks. Comet fragments remain the most viable explanation, and that nearby M-dwarf (about 885 AU away from KIC 8462852) is certainly a candidate for the kind of system disrupter we are looking for. That leaves the comet explanation as the leading natural solution. A non-natural explanation may raise eyebrows, but as I said yesterday, there is nothing in physics that precludes the existence of other civilizations or of engineering on scales well beyond our own. No one is arguing for anything other than full and impartial analysis that incorporates SETI possibilities.

Jason Wright puts the case this way:

We have in KIC 8462 a system with all of the hallmarks of a Dyson swarm… : aperiodic events of almost arbitrary depth, duration, and complexity. Historically, targeted SETI has followed a reasonable strategy of spending its most intense efforts on the most promising targets. Given this object’s qualitative uniqueness, given that even contrived natural explanations appear inadequate, and given predictions that Kepler would be able to detect large alien megastructures via anomalies like these, we feel [it] is the most promising stellar SETI target discovered to date. We suggest that KIC 8462 warrants significant interest from SETI in addition to traditional astrophysical study, and that searches for similar, less obvious objects in the Kepler data set are a compelling exercise.

As I mentioned, the Wright paper discusses the broader question of how we can distinguish potential artificial megastructures from exoplanet signatures, and also looks at other anomalous objects, like KIC 12557548 and CoRoT-29, whose quirks have been well explained by natural models. I want to go through the rest of this paper when we return to it in about ten days.

The paper is Wright et al., “The ? Search for Extraterrestrial Civilizations with Large Energy Supplies. IV. The Signatures and Information Content of Transiting Megastructures,” submitted to The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

And nothing would be against someone using comets to build megastructures…

In a natural way it makes sense, why waste energy and time building metallic or dense rigid structures when you can just live on the volatile’s you need as lifeforms…

The lack of periodicity of the light curves seems to suggest that the occulting objects are either not in regular orbits, or relatively far away from the star. I would think that both of these would argue against artificial structures, at least any that are intended to gather energy. I would think that a civilization building a Dyson swarm would want its energy-gathering surfaces to be relatively close to the star, and in regular orbits such that they don’t occlude each other, in order to maximize efficiency. The very irregularity of these signals seems to me to make it more likely that they are some natural but (relatively) transient phenomenon. A more convincing signal of artificiality to me would be multiple, rapid, regularly spaced transits of the same size that suggest multiple objects of the same size and shape all in the same orbit.

Happy Vacation…

Now and then I imagined Paul Gilster was actually an advanced computer feeding the community astronomical challenges day after day after day…

Don’t wander away too far…

Has anyone done any research on what effect a MegaSail (eg laser/microwave beamed) Interstellar probe/vehicle would have on the light curve of a star if it (or a group of such probes/vehicles) crossed in front of its host star as viewed from Earth?

The variety and shape of the light curves indicate complex multi-object effects are being observed at KIC 8462852 and maybe a fleet of massive “Sails” should also be considered.

It will be very interesting, as future datasets become available, to see if what is happening at KIC 8462852 is a recurring or non-recurring phenomena.

My question is, since Kepler viewed such a narrow area of the galaxy for just a few years and this unusual phenomenon did show up in its data, does this mean we either just got very lucky or that there are many more WTFs?

And if they are due to alien astroengineering, does that mean we have lots of celestial neighbors redecorating the galaxy? Or do exoplanets collide with each other and exocomets swarm in large numbers far more often than we knew?

Whatever WTF 001 is, the good news is that at least some professional scientists are at last willing to publicly admit and look outside their paradigms. Which is always good for science and our cultural expansion, whether WTF 001 is artificial or not. It is the year 2015, after all.

I’ve speculated within the last few years in comments on this website a cosmic signalling method in which a series of occulters are situated in an orbit designed to encode information on the lightcurve when viewed from afar, assuming one can recognize and decode it. I agree a natural explanation is still the most likely, but how wonderful it is we have a potential calling-card to investigate!

The Universe Today’s nice and informative take on this subject:

http://www.universetoday.com/122865/whats-orbiting-kic-8462852-shattered-comet-or-alien-megastructure/

To quote:

What about a collision between two planets? That would generate lots of material along with huge clouds of dust that could easily choke off a star’s light in rapid and irregular fashion.

A great idea except that dust absorbs light from its host star, warms up and glows in infrared light. We should be able to see this “infrared excess” if it were there, but instead KIC 8462852 beams the expected amount of infrared for a star of its class and not a jot more. There’s also no evidence in data taken by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) several years previously that a dust-releasing collision happened around the star.

James Stilwell writes:

Actually, I uploaded myself a few years back. Very interesting in here!

I agree with Tulse. If each of the big dips in the light curves are individual objects, then they are quite far out from the star, possibly beyond te habitable zone. This makes it unlikely that they are large habitats collecting energy, or collectors which should be close to the star for better efficiency. The Boyajian paper has rapid 1 day fluctuations that are attributed to some stellar feature (star spots), although theoretically they could be collectors, although they would be in a very close orbit if so.

If they are c9ollectors or habitats, where is the IR signal that we would expect when searching for Dyson swarms – it is absent. If we posit that they do not emit IR, then why bother looking for KII and KIII signals using this approach?

I’m inclined to doubt an artificial explanation, preferring large, irregular objects far from the star. If you want something artificial/intelligent, perhaps something more like Hoyle’s “Black Cloud”.

I’m not a scientist, and I read as much Sci-Fi as anyone.

But I am surprised people are just leaping at an ET explanation.

I think it’s both prudent and driven by history to exhaustively consider the most conservative possibilities at the greatest length before getting too excited.

The Fermi Paradox is not about nothing. ET has had deep time to come see us, not wait for us to spot him.

The fact that there’s a convenient M dwarf nearby to perturb the rocks is glaring.

I will be interested to hear by what additional means this object can be studied both from the ground and space. Science discovery is fascinating, and Kepler has turned over lots of astronomical expectations already, ironically while not finding what it was looking for.

Paul: “Actually, I uploaded myself a few years back. Very interesting in here!”

For your sake I hope it wasn’t to a Windows-based machine. Perhaps that would be a download, not upload.

I’ve read the popular press accounts but not the paper yet: have 3 questions:

1. how can they know its not periodic? you observe for N days and you can only say that in N days, that if the occluding object was orbital, its orbit is >N days.

2. can you not tell from the exact shape of the light curve dip, what shape the occulter is?

3. why do we presume the occulter(s) is near the star? what if it is only 500 LY, for eg, from us and merely in the line of sight? it could be debris and since it’s not associated with the star, there is no IR excess ?

22% and 15% of the star occulted? Those are some HUGE comets!

Ron S writes:

I’ve been following this story across various websites including this one.

What I find interesting is what it would imply about the general universe and the prevalence of technological life if it turns out to be an alien BDO.

Premise: An advanced alien CIV exists less than 1500ly from Earth

Inference: Advanced CIV’s litter the Milky Way

Implications: Statistically there should be vast numbers of technological CIV’s with evidence of megastructure engineering everywhere we look.

The odds are against us having the only other Tech CIV in the galaxy on our relative doorstep. Therefore it is common, so why do we not see more evidence?

@Tom Mazanec Does that not depend on what distance the “comets” are from the star?

An ignorant thought here, I have either read or heard somewhere about an idea using a star as an anti-matter factory, the production process would be enough to dim a star. Some people think collecting solar energy is “so yesterday”, the future is always matter/antimatter distillery method. Of course, this is all pure speculation so please don’t even bother spending too much time on this.

Please enjoy your holiday!

As to this discovery,forgetting for a moment that it might be just as well natural, let us use our imagination and think what we could deduct from its existence(and other known candidates for Dyson Spheres detected in previous searches).

First of all it seems very isolated, and not a complete Dyson Sphere(although such complete one is considered today unlikely).

It is located around a hot F star I understand correctly. Such stars while not too friendly to life, don’t prohibit life from forming(there is an entry on Centauri Dreams about their habitability).

It would seem to me that it would more likely serve as an energy collecting structure than habitable space, especially considering its isolated nature and isolated nature of other candidates.

Such structure would indicate that advanced civilizations are not keen on expansion and limitless growth, but rather pursue isolated projects and shy away from contact, although they do not hide their presence fearing some active Great Filter of artificial nature.

Would such structure serve computational needs or as gathering point for intensive energy consumption(lets say for example as source of beamed energy for interstellar travel?). Interesting thing to speculate.

However the fact that it relatively close in cosmological scale would indicate that such civilization unless highly isolationist, would be able to detect our planet long time, and seeing its biosphere decided against any active interaction or contact.

I think such discovery(forgetting again the most plausible natural source of this event) would indicate Galaxy of isolated islands of civilization focused on their selves and not bound by biological need to constantly expand. Perhaps in scarce and isolated communication(WOW signal?) and travel across vast distances(which brings to my mind a question.How far is this start from other Dyson candidates we have found before? Or if there is any pattern we can observe in their locations?).

http://home.fnal.gov/~carrigan/infrared_astronomy/Other_searches.htm

There’s one odd feature of the flux curve that’s not mentioned in either the Wright or the Boyajian paper: the events at D1520 and D1570 have different magnitudes but qualitatively similar shapes. I applied an arbitrary horizontal scaling to the D1520 event to see how close I could get to the later event, and the result is somewhat interesting.

If the similarity isn’t coincidence, it can mean only a couple of things: These events represent the same object at different places (distances) in its orbit; or these are two similarly shaped objects. If it’s two objects, then they’re either the same size but different distances from the star, or they have similar structure but different sizes.

Speculating way beyond the data: centered between these two events is another, symmetrical event that looks pretty clearly like a ringed planet: small dip / big dip / small dip. Imagine that the two anomalous objects are placed at Lagrange points preceding and trailing the ringed world, like NASA’s STEREO satellites. :)

Paul have a great holiday you have earned it.

@Hiro October 16, 2015 at 18:07

‘An ignorant thought here, I have either read or heard somewhere about an idea using a star as an anti-matter factory, the production process would be enough to dim a star. Some people think collecting solar energy is “so yesterday”, the future is always matter/antimatter distillery method. Of course, this is all pure speculation so please don’t even bother spending too much time on this.’

Although anti matter is a very powerful fuel storing it is a real challenge!

My money is on a ringed world orbiting beyond the snow line perhaps with a precession orbit like mercury, ring structures like Saturn has are huge and could account at least for the dimming part.

http://www-astro.physics.ox.ac.uk/~imh/ELT/Book/SandP/SandP_book_29apr05_files/image020.jpg

Just found this article on artificial transits and what they may look like.

http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1086/430437/pdf;jsessionid=D37979BA4952D1F973F00AA99DB47A89.c1

@James Galasyn — If the similarity between the D1520 and D1570 events is due to seeing the occlusion effects of the same object at different places (distances) in its orbit, then this would seem to fit with the idea of a comet with a very large coma (comas can be as large as the planet Jupiter and are mostly opaque), or a cluster of large comets, spiralling towards the star with an observed orbital period of about 50 days. This spiralling comet, or cluster of comets, would account for the largest reductions in flux in the light curve, but there are clearly other objects in the data. Presumably the large comet would eventually impact with the star but the Kepler data ends before that event. But that still leaves us with the problem of the star’s observed lack of IR excess which contradicts the hypothesis of large amounts of cometary dust in the system.

A fleet of light sails fleeing a disaster?

@James Galasyn I tried to do the same thing from the paper by T. S. Boyajian, D. M. LaCourse et al. Fortunately the images have enough resolution. Yes the two events you mention at D1520 & D1570 (plus the nice and symmetrical event “ringed world” in the middle) are very similar in shape. They seem scaled, not equal, but similar. Perhaps the shape could be influenced in some way from the sampling frequency by Kepler, so even the same objects may look different. Very interesting story anyway!

So long as everyone is speculating about Dyson swarms, let me just throw another wild and unproven hypothesis into the mix. How about destroyed worlds? We are seeing lots of irregular light curves from KIC 8462, with some suggesting pretty massive objects (22% light dip suggests something massive to me). These large drops in light output from KIC suggest they are too massive to be comet nuclei. People have talked about alien megastructures. But what if we are seeing the remnants of a solar system, where the planets have all been destroyed or broken up into fragments, leaving just the star intact?

Would that imply alien megastructures closer into the star, and the ETs only needed a portion of the planetary material in the solar system, discarding the rest further out on the edge of KIC’s solar system? Or, perhaps more dramatically, something destroyed the planets, leaving only fragments, but left the star intact.

If we are speculating about aliens, and alien megastructures, then why not berserkers? Worrying that KIC is only 1470 light years away!

Just a wild idea, for which there is no hard evidence, but nor is there any evidence for Dyson swarms.

This morning the SETI Institute tweeted:

@SETIInstitute: Star KIC 8462852 is in the news. Its dimming might be due to alien constructions. Hang tight: The Allen Telescope Array is looking.

It seems as though the popularity of this report is greasing the wheels a bit already.

The third feature which looks like a dimmed first feature may be due to gravity darkening, a process that occurs when the stars equator rotates rapidly affecting the amount of light emitted. Now are there two objects or just one?

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1308.0629v1.pdf

I’m no expert by any stretch, but two things come to mind relating to US humans. 1) Given the natural and reasonable skeptical approach of the sciences to this question with huge implications, I wonder if the “Conservative” viewpoint is not almost destined to win out? In short, unless ET waves a big “WERE HERE!” sign, no one in the scientific community is going to have the guts to make the “Intelligence” call. They will bend, stretch and torture a natural explanation out of the data, for the simple reason they don’t want to have to face the aftermath of such a discovery. It would bring out every kook in the woodwork , and who knows the social impact? AND, how will the governments react to this? Not well, I suspect.

2) ANY attempt by humans to understand a truly ALIEN intelligence is almost doomed to fail. What might look unlikely or impractical given our evolutionary and cultural background may appear far different to another civilization composed of WHAT?- evolved through what chain of life, under what circumstances and conditions we will NOT have experienced.

In short, I promise you the scales are already weighted against anything but a natural explanation, even if that explanation is FALSE. No one will have the guts to make the call.

@Michael: “Although anti matter is a very powerful fuel storing it is a real challenge!”

^For us right now, but it’ll be easy when someone manages to find a better solution in 22nd – 23rd century.

By the way, no one has ever mentioned that dark matter is also an informal answer to this question. Even though we know almost nothing about this mysterious dark matter, but it still sounds better than saying LGM did it.

Tulse wrote:

“The lack of periodicity of the light curves seems to suggest that the occulting objects are either not in regular orbits, or relatively far away from the star. I would think that both of these would argue against artificial structures, at least any that are intended to gather energy. I would think that a civilization building a Dyson swarm would want its energy-gathering surfaces to be relatively close to the star, and in regular orbits such that they don’t occlude each other, in order to maximize efficiency”

Perhaps it isn’t a swarm to collect energy from the star looking inward but instead, to collect information about the galaxy looking outward?

Wouldn’t a giant multi-spectral (LUVIOR) interferometer have advantages being located further away from the star wouldn’t it?

@Steve White – we should be very conservative. Alien discovery is an extraordinary claim which will require extraordinary proof. If we don’t have that proof, then better to admit it rather that claim that we have ruled out all natural phenomena (that we can think of) and that therefore aliens are the answer. This is very close to the thinking of creationists and claims for the existence of God.

” In short, unless ET waves a big “WERE HERE!” sign, no one in the scientific community is going to have the guts to make the “Intelligence” call. They will bend, stretch and torture a natural explanation out of the data, for the simple reason they don’t want to have to face the aftermath of such a discovery.”

That is unfortunate side trait of Dyson Sphere candidates,they are very similar to natural phenomena and we have no real means of confirming if the candidate is a Dyson Sphere or natural object. They were a couple of strong Dyson Sphere candidates in the past, some were part of SETI listening programs, some were not.

http://space.alglobus.net/papers/PDSpaper2.pdf

http://articles.adsabs.harvard.edu//full/2009ASPC..420..415C/0000418.000.html

Look for IRAS 20369+5131 and G 357 .3-1.3 as examples but there are some more.

” This implies either occulters with star-sized gaps, multiple, overlapping transit events, or complex non-Keplerian motion.”

. ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

Well!

Remember when we first proposed “Dyson Dots” (in ~2000, long before our JBIS article) we call them “raidation-levitated sunshades in no-Keplerian orbits inside the Sun-Earth L1 point”. Think also of the late great Robert Forward’s “pole sitters”.

So, if “non-Keplerian” behavior is indeed a part of the explanation for this stellar oddity, then we could be seeing radiation levitation.

RGK3

If a passing star disrupted the system and sent swarms of comets inward then a series of natural events could be the culprit.

ie. A few of the comets coming too close to the star and falling apart could be creating huge clouds of ice and water, allowing it to block larger amounts of the star’s light than a solid object would. There could be more than one such instance, creating a number of clouds.

ie. Impacts of the comets with planets, maybe ice or water worlds, could have created a cloud of water around a number of the planets. It could even be a process that would continue for millions of years until the system once again sorts itself out.

Either, or both, would create a number of large objects that would block huge amounts of the star’s light.

Anyway, I know little of physics so I’m just speculating, but one thing for sure – one can’t say SETI has been boring this week.

If somehow this star system was showing off the labors of advanced life…

Those folks would know, for their part, everything about us. Well, certainly about earth. They would have known it for a very long time.

As it stands today, in our stupidly primitive state, we are surveying the neighboring environs of the galaxy daily. The time is not far off when we will discover and catalog the nearest “blue marble” planets. We will analyze the light of their host stars light as it passes through their planetary atmospheres, to see of what it is made up , detecting in the process the by products of any , life chemistry going on in there.

And that’s us, the primitive guys. Imagine what the advanced folks could do. They would have seen earth long ago. Yet all is silence.

These are, whatever they are, natural processes at work in this star system. It’s a great, a fantastic, opportunity to expand our knowledge about how nature works. Lets enjoy the ride and not get out of control.

My sense is that now, while there is still resistance to serious consideration of aliens among the science community, this is beginning to change. We live in an exciting time for SETI, and also consider that today with the internet and interconnectedness of thoughts, theories, and ideas, and the exchange of those, it potentially makes an amazing discovery more likely, as old dogmas begin to fade as more people share ideas and concepts. While I agree it would be nice to have irrefutable evidence of an alien civilization, and we may yet get it, let’s hold our breath and keep our fingers crosses, it’s also likely that we might have to dig a bit below the surface to find evidence of aliens. They may not communicate in radio for instance. We might simply have to find evidence of their technology, and not an actual signal. Things like that may lead us to the discovery, and not some dramatic prime number radio transmission. I’m not saying or prepared to claim that KIC8462 is that candidate yet until we know more data, but you can’t “torture” a natural explanation if all other reasonable scenarios don’t add up or match the findings. And the beauty of this unlike with the Wow signal is that the dimmings were repeated over a 2-4 year period so when SETI starts honing in on it, they should repeat again, allowing for more conclusive determinations as to what is causing the star to dim so dramatically. It may be easily explained away, we may find evidence of a giant cometary orbit, or other natural phenomena, but if the Kepler findings repeat, and nothing really fits, well, you have to start seriously considering that it could be an alien structure.

I disagree that “scientists don’t want to face the aftermath of such a discovery”. Of course, science must be checked, verified, and double-verified as much as possible, and this star should be intensely studied as long as possible to test different theories, in an unbiased way. But if indeed it is aliens, scientists would probably face mostly positive feedback and reaction from the vast majority of rational sane people. Of course, the typical ideological inward-looking nutcases would have problems with it, but they’d be in the minority, as they usually are with new discoveries.

We have to follow the facts and the evidence, of the further studies of this star. But as I said, we may not receive the dramatic “hello” via radio telescope that so many expect from an advanced civilization. I think it more likely that we’ll detect signs of their technology and visual evidence of their existence, also because radio can be so hard to disseminate. I still fully support radio astronomy though just in the case that it does work.

To paraphrase Carl Sagan, “extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence”. Very true, but we must remember that an advanced alien species’ technology might be more subtle than we expect, and so we might have to think outside the box a bit to find something. But if there is something going on at KIC8462 we should be able to at least detect it visually with futher study so that’s encouraging.

ALEX TOLLEY: Thank you for your comment, but I have a follow up observation. I notice the phrase, we must rule “out all natural phenomena (that we can think of) and that therefore aliens are the answer.” This is perhaps more of a philosophical question than a scientific one, but, oh well. In ruling out all other things “Natural”, are we not in fact saying LIFE is unnatural? -including us and any suspected aliens. If the universe bagan with a Big Bang, followed a stellar evolution and the emergence of life , on our world -or any others- through biological evolution, is it not just as “natural” as a swarm of comets? In pushing LIFE itself on to the back burner, do we not already prejudge the outcome of any given search for OTHER life?

In legal terms -which I probably have more experience with- people often misstate the degree of “Reasonable doubt” to “Beyond the shadow of a doubt”, which is impossible to meet. You can alway concoct -or torture- some doubt concerning ANY question, scientific, legal, or just everyday. And, with a hidden bias AGAINST life, especially alien life, as I said earlier, the conclusion I believe is foreordained regardless of data.

They will -not a one of them- have the guts to call it. They will write it off as “Natural, not sure what, but natural”, failing to acknowledge life itself- as an explanation- is part of that nature and can, and DOES, leave it’s mark, if we learn to see it.

Thank you for listening.

@Michael, thanks for the paper on gravity darkening! It explains the asymmetrical event at D793. Also, it goes a long way toward capturing the strangest events at D1520 and D1570. It’s convincing enough that I’m willing to call it for Barnes, et al: “An oblique transit path across a gravity-darkened, oblate star leads to the long transit duration and asymmetric lightcurve evident in the photometric data.”

If there is no infrared excess then it is not dust but it could be ice because ice and particularly snow is quite reflective in the U.V part of the spectrum allowing a lot of dimming. Now if it is ice it can’t be too close to the star because it would disappear sharpish so the object causing the dips could be just around the ice line of the F3 star.

So could it be a planet (the symmetrical dip between the two other deeper dips) which has an icy ring around it to the cloud tops and some moons which also have accretions rings around them. The disruption could have been caused to a older formed planet of the red dwarf which had some of its moons disrupted by the close encounter with the F3 star system to form this reconfiguration and by chance has been detected by Kepler. It could be equally the F3 stars planet/moons that was disrupted and push closer to the star were they are cooking off ices.

This is a light curve for a comet like planet which sort of matches the first deep dip and it could be that the first dip is an object from the dwarf or F3 star cooking off its icy surface also due to the disruption event.

http://inspirehep.net/record/1128188/files/lctranzit.png

Hi all!

Been a while since I’ve posted.

Love all the ideas here.

Clearly, it’s the Death Star and a massive alien fleet in transit ; )

As a layman looking at this, I too would love this to be ‘alien’, however, at this point it’s leaning ‘natural’.

The thing is, all these ideas we have are human ideas of what aliens are. If it were a say Type II-ish (Dyson) they’d likely be a *bit* different from our conceptualizations and well, unlikely build a Dyson.

But lets say they did. Type II’s guaranteed benevolent? I’d give same odds as flipping a coin. If they are biological (as we know it) and still growing in resource needs, Earth would likely be akin to today’s rare earth metals in value.

Although not the only one, we’re a pretty unique blue marble.

We are making assumptions and filling in blanks. Let’s take the likeliest fillers first. Phil Plait (Slate) has an excellent article on not ruling anything out, but focusing first on what’s most likely.

That said, the unlikelihood of aliens definitely is not a reason to totally ignore it. Rather, it must be a consideration until evidence says otherwise. Because we must know.

Y’know, just in case it IS a galactic empire ; )

(Everyone keep looking!)

I’ve changed my mind, and I don’t think it’s necessary to invoke a ring system to explain the symmetrical event at D1540 — it’s similar to Fig 6. in Barnes, et al.

@Steve White -“Natural” is used in a different sense. Natural Sciences study all phenomena from physics to biology, but exclude those that are due to agency, e.g. psychology, economics, etc.

This is important because natural phenomena don’t try to fool us deliberately and will fill follow laws, whilst humans, in particular, can change behaviors and generate new things.

There is certainly an argument that human artifacts are just our “extended phenotype” (Dawkins), but in this case, alien artifacts are clearly artificial, not natural.

Could it be some unresolved binary brown dwarf? The only thing I can come up with as far as a natural explanation is either a planetary entrapment by KIC8462, I just have trouble with the comet theory, no infrared signatures were observed, and even it was icy, this would seem unlikely. And isn’t the red dwarf star fairly close to KIC8462? So maybe there’s something to that. Otherwise I can’t think of anything it could be other than some type of large scale technological structures, they said that they had strange different shapes though, which I guess COULD be cometary fragments, but again I keep coming back to the observed dimmings, I mean 15% and 22% are HUGE drops, so whatever this is must be mind-boggling. Each time I try to construct a natural-cause theory, there are holes in it. I literally can’t wait to see what further data shows!

An alien species would come from their own unique evolutionary and biological circumstances so they’ll likely not resemble humans at all. Perhaps there are certain traits in nature that are inherently beneficial, such as having appendages, digits, eyes, etc, but the number/type/variation of this again is purely guesswork, given each planet’s unique circumstances, and how random evolution is. If the clock were turned back again on Earth, assuming intelligence arose, it might very well have been reptilian, or something totally different from mammals and humans. This will be true on any alien world, each one will likely vary quite a bit.

Personally I tend to think life in general in terms of large unintelligent beasts might be fairly common throughout the cosmos, in other words, I’m of the opinion that the path from microscopic life to large complex beasts, such as what was on earth for most of its history before humans, is more common than intelligent life. I suspect the leap from unintelligent beasts to intelligence may be much more rare than simpler non-sentient life. But just a guess on my part.

Then the question is IF intelligence manages to arise, is it inevitable that they will go on to develop high technology? That’s another question. Humans attained intelligence hundreds of thousands of years ago, but didn’t develop high technology until the 20th century. I personally think once a species does manage to attain sentience and intelligence, then it’s eventually going to naturally gravitate towards some form of technology, but the path may be slower, faster than our experience here. And then of course the problem of can they exist with that technology without destroying themselves in the blink of an eye. These are all worth considering in thinking about KIC8462.

All that being said I believe that the Cosmos is so huge and even our own Milky Way is so large that the numbers alone are very conducive to at least a handful of advanced civilizations. But the nearest may be very far away, and likely would be far ahead of us. Maybe so far ahead that we couldn’t recognize it as easily as we might think.

Another point about Type II Kardashevs, if that’s what we’re looking at with KIC8462..If it is some form of Dyson structure, and let’s say we’re seeing pieces of one, we could speculate that either we’re seeing them as they reached a peak of their technology, beginning to harness their star’s power, or perhaps, they had run into some trouble, depleted all their resources and so constructed a Dyson structure as a desperate attempt to find a massive steady source of power. Other speculation, perhaps, in tandem with this, they happened to be a curious species, and decided that in doing this, they realized that such immense dimmings of the star would be visible to any other intelligent beings on other worlds, so they decided that would be an added scientific curiosity bonus for them, while the main objective was to find energy. So maybe there’s a hidden beacon in their dimmings of the star, again assuming that it could be aliens.

I think it would be 50/50 whether they’d be “benevolent” or not. Likely they’d be so far ahead of us that we’d be like insects to them. But if they were a curious species still, they’d still be interested in other primitive forms of sentience. But I agree with Dr. Hawking, we should always err on the side of caution, in this case, if it were aliens, they’d be 1500 light years away so the distance alone would ensure protection for us assuming they were highly hostile. But it’s still in my opinion as a layperson who speculates and writes about these things regularly to be very cautious, if you’re dealing with another intelligent species, you have to be cautious and I’d observe them silently before ever making ourselves known. Even though any attempt at contact might be useless because a message wouldn’t reach them for 1500 years, and besides, they might already be gone by now anyway, we’re seeing them as they were 1500 years ago..Again, purely speculative, but fun to think about the possibilities if the remote chance that KIC8462 is alien.

In radio astronomy we have the “Extreme Scattering Events”.

These seem to have been largely ignored by the wider community.

Walker et al hypothesised ESE’s were caused by a large population of AU-sized gas clouds, which sometimes pass our line of sight to the source being observed.

Maybe what we have here is the optical equivalent of an ESE? Is this conceivable?

Preparing For Contact

By Brian McConnel

October 18, 2015

I’ve been writing about and doing SETI related research for almost 20 years now. The discovery of Kepler object KIC 8462852 (renamed WTF-001 by SETI researchers) is without doubt the most interesting SETI candidate found to date. Most likely, it will turn out to have a natural explanation (I am putting my money on gravitational lensing by a foreground object), but at this point an artificial (alien) explanation cannot be ruled out. This object will receive a great deal of attention in the coming weeks and months, and we’ll know soon enough if this is or isn’t first evidence of another technological civilization. We are fortunate that this is a persistent phenomenon, and not a transient like the “Wow” signal, so we have a good chance of figuring out what it is.

Most of my research has focused on message analysis and composition, as well as thinking through what systems should be in place to support a large scale effort to comprehend an alien transmission. In this article I’ll discuss what will happen if SETI radio or optical surveys reveal evidence of artificial signals emanating from this system.

The first step after confirming a signal, be it a radio/microwave or optical transmission, will be to analyze it in greater detail to determine if the signal is modulated or not. We shouldn’t assume that they will be trying to communicate. Given the apparent size of the objects orbiting KIC 8462852, it would not be surprising to intercept leakage from a beamed power link, for example.

Full article here:

https://medium.com/@brianmsf/preparing-for-contact-b6c579a0059

To quote:

In cases 1 and 2, we will receive exactly one bit of information, “alien civilizations exist = True”. This is still profoundly important, but for a variety of reasons, I hope that these scenarios do not take place. The problem is that while SETI researchers will be honest about not being able to extract information from the signal, that’s not going to stop dishonest people from saying that they have, or that there is some sort of conspiracy to conceal this information from the public.

It’s a safe bet that every charlatan on the planet will exploit this opportunity, and that there will be no shortage of gullible people who will believe them. This will be a destabilizing and potentially dangerous situation. Many people are already primed to believe elaborate conspiracy theories regarding UFOs, so it’s easy to see how things could get out of hand, and how people could get killed (see Heaven’s Gate).

In case 3, we should quickly have systems in place to extract and record data from the signal as we receive it. This information will be made available to scientists and the public at large via the Internet. We’ll still have the cranks to deal with, but at least there will be a science based system for analyzing and comprehending what we find.

What will happen from there will be a global effort to comprehend whatever it represents. There is a small group of technical experts who’ve done serious work on interstellar message analysis and comprehension (you could fit us all in a small conference room), and they’ll test their ideas and assumptions against the data, as will the public at large. I personally think that the most important insights in comprehending such a transmission will come from people who are not currently involved in SETI.

Why it’s so hard for astronomers to discuss the possibility of alien life

The internet went crazy this week over a strange star observed by NASA’s Kepler spacecraft

By Loren Grush on October 16, 2015 12:10 pm

The internet has been abuzz this week over the possibility of intelligent alien life somewhere in our galaxy. This time, an article published by The Atlantic set off the storm. The story details how NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler spacecraft has spotted a strange star in the Milky Way named KIC 8462852. The star exhibits weird fluctuations in its brightness, leading a few astronomers to propose — among many other ideas — that maybe a swarm of alien megastructures is orbiting around the object.

“I was fascinated by how crazy it looked,” Jason Wright, an astronomer from Penn State University who studied the star, told The Atlantic. “Aliens should always be the very last hypothesis you consider, but this looked like something you would expect an alien civilization to build.” Wright said he is working on a paper that explores the theory further.

Full article here:

http://www.theverge.com/2015/10/16/9553033/kepler-alien-megastructure-dyson-sphere-kic-8462852

To quote:

“It’s just irresponsible reporting. Because if you take a look at the paper — the scientific paper the authors wrote — [that idea] is not really even in there,” Seager, astronomer and planetary scientist at MIT, told The Verge.

Seager noted this has long been a problem for astronomy. Whenever astronomers talk about potential evidence for alien life, their statements are often overblown. It’s an unfortunate byproduct of the field, she said, because discussing how to find extraterrestrial beings is an important part of exoplanet science. “We definitely visit that question a lot: How will we know? What evidence does it take?” she said.

…

But in regards to the frenzy surrounding this particular star, Seager said that jumping to the alien conclusion is way too premature. Inexplicable stars like KIC 8462852 are observed all the time in astronomy. “It’s correct that this star seems to be anomalous and unique in all of the Kepler star data, but there are other one-off objects like this in astronomy,” said Seager. “Not all puzzles are solved right away. Something’s going in front of the star, but we don’t know what.”

NASA also cautions not to get too enthusiastic, since Wright’s paper on the alien theory hasn’t even been published yet. “The paper, as far as I know is not yet accepted,” said Dr. Steve Howell, a Kepler project scientist at NASA Ames Research Center. “We have this belief in the scientific community that until a paper is accepted, what’s said there and the results may change, so I think until this gets accepted we should scientifically be cautious. That’s kind of how things work.”

Until that happens, Seager said speculating any further is just silly. “We love media attention; it’s great for the field. But I just find this a little awkward.”

They may be waiting until January, 2016 to use the VLA to SETI WTF 001, but not at the ATA:

http://www.space.com/30855-alien-life-search-kepler-megastructure.html

AmericaSpace’s take on the subject:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=87587

CNET Magazine’s interview with the key folks in this event:

http://www.cnet.com/news/the-full-story-behind-the-alien-megastructures-scientists-may-have-found-but-probably-didnt/