Keeping up with a site like this can be a daunting task, especially when intriguing papers can pop up at any time and announcements of new finds by our spacecraft come in clusters. But site maintenance itself can be tricky. Recently Centauri Dreams regular Tom Mazanec wrote in with a project to be added to the links on the home page and before long, with my encouragement, he had sent a number of solid suggestions on exoplanet projects both Earth- and space-based, most of which have now been added. My thanks to Tom and all those who have at various times caught a broken link or added a suggestion for new links or stories.

We begin the week looking at work discussed at the Division for Planetary Sciences meeting in Maryland, starting with the continuing bounty coming in from New Horizons. I always like to quote Alan Stern, because as principal investigator for New Horizons, he is not only its chief spokesman but the guiding force that saw this mission become a reality. And I think he’s absolutely on target when he points to how fulsome a discovery Pluto is turning out to be:

“It’s hard to imagine how rapidly our view of Pluto and its moons are evolving as new data stream in each week,” says Stern. “As the discoveries pour in from those data, Pluto is becoming a star of the solar system. Moreover, I’d wager that for most planetary scientists, any one or two of our latest major findings on one world would be considered astounding. To have them all is simply incredible.”

Image: Pluto and Charon are revealing themselves as worlds of profound complexity. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

All this with a flyby, leading me to wonder what we might find with a Pluto orbiter.

Think about Voyager. It opened our eyes to new worlds for this first time. It flew by Io and gave us active volcanoes. It flew by Triton and we saw weird ‘cantaloupe terrain’ and nitrogen geysers. All these stay fixed in my mind as I remember first learning about them. But what New Horizons is showing us ranges from bizarre moons to possible ice volcanoes, the huge satellite Charon in a system that is practically a binary ‘planet,’ and surface features that tell us about an active world that was once thought to be inert. Who thought Pluto/Charon would be this complex!

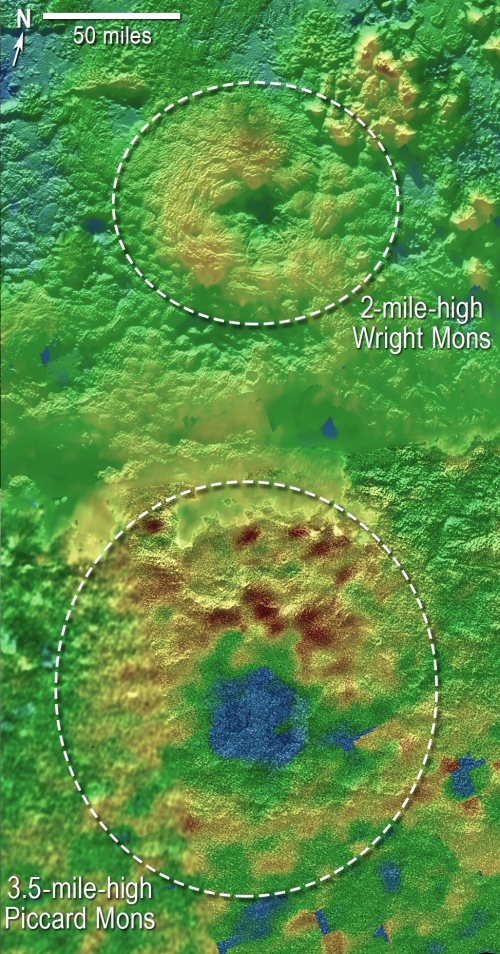

Wright Mons and Piccard Mons, as it turns out, each appear to have a hole at their summit, the signature of a volcano, but one expected to cough up water ice, nitrogen, ammonia or methane in a melted slurry rather than lava. We can’t push this too far, because on a world about which we have so much to learn, we may be in for yet another surprise. And Oliver White, a postdoctoral researcher at NASA Ames, points out another of the unknowns:

“If they are volcanic, then the summit depression would likely have formed via collapse as material is erupted from underneath. The strange hummocky texture of the mountain flanks may represent volcanic flows of some sort that have travelled down from the summit region and onto the plains beyond, but why they are hummocky, and what they are made of, we don’t yet know.”

Image: Scientists using New Horizons images of Pluto’s surface to make 3-D topographic maps have discovered that two of Pluto’s mountains, informally named Wright Mons and Piccard Mons, could possibly be ice volcanoes. The color is shown to depict changes in elevation, with blue indicating lower terrain and brown showing higher elevation; green terrains are at intermediate heights. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

As this JHU/APL news release makes clear, Pluto’s surface is also showing us far more textures than we might have expected. Why do we see so few small craters? Neither Pluto nor Charon give us many of these, casting doubt on the older model of Kuiper Belt objects formed by the accumulation of small objects. Now you can see why 2014 MU69 is beginning to loom so large. This KBO may be a pristine primordial planetesimal, the first ever to be explored. Assuming the New Horizons mission is extended, a flyby of 2014 MU69 will give us another look at a class of objects that may have been formed quickly and at close to their current size.

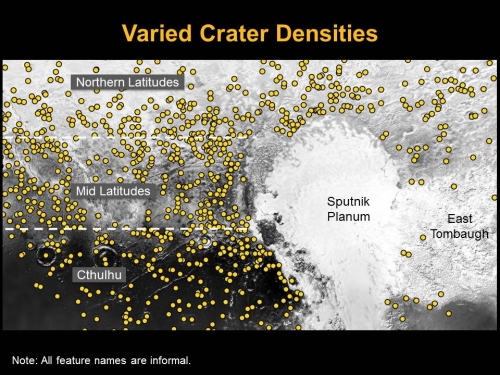

But we still have a lot of explaining to do re Pluto’s surface itself. Trying to determine the age of a surface is often a matter of counting the crater impacts to see what has accumulated over time (think of the relatively smooth surface of Europa, which indicates continuing resurfacing that obscures impacts). On Pluto, we do find surfaces that point to the earliest era of the Solar System four billion years ago, but we also see things like Sputnik Planum, whose smooth and impact-free terrain looks to have been formed within the past ten million years, an eyeblink in astronomical time.

Image: A slide from Oliver White’s presentation at DPS, showing crater densities on Pluto’s surface. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

Other terrains on Pluto look to be somewhere in between, with evidence of cratering extending back not nearly as far as the oldest areas. So is Sputnik Planum, which is on the left of Pluto’s heart-shaped feature, an anomaly, or a marker for a surface that has been geologically active for much of its history? We’re looking at evidence for how objects in the outer Solar System formed, again a splendid reason to back the extension of New Horizons to 2014 MU69.

More on Pluto/Charon and the findings discussed at the DPS meeting tomorrow.

Are the pictures of Pluto and Charon at the start of the article, are they the TRUE colors of those two moons or planets or whatever they call them now ? Could you post some pictures of the ACTUAL coloration of these particular bodies, please ?

Isn’t this pretty close to what people were saying when MESSENGER started sending back Mercury data? It’s almost like every planet has a unique composition and history…like everytime we send a probe to or past an unexplored one, we learn things we didn’t even expect to learn!

Is it just me, or does Sputnik Planum + East Tombaugh look like a splat from the NNW?

There may not be much visible water ice around an ice volcano because a thin coating of the volatile N2 and methane ices would cover any water ice. The regions where water ice was detected tended to be high slope areas where any covering non-water ices might slough off.

The Sputnik Planum area was shown to be the area with the lowest average sunlight averaged of the Pluto year, somewhat analogous to Earth’s polar regions. It may be a deep deposit of N2 ice which has a higher density than water ice. Thus the area is depressed relative to the surounding mountains and is likely to be a very old feature. Its surface however is refreshed by seasonal N2 ice deposits.

If nothing else Pluto is certainly on the way to the next star systems:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/brucedorminey/2015/11/23/will-nasa-ever-send-astronauts-to-pluto/

And if humans do colonize the outer system belts, certainly Pluto and its moons will be high on the list of places to live and work upon.