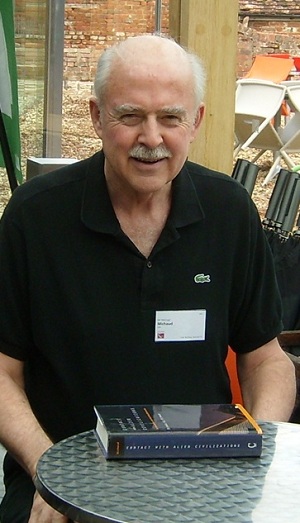

In the heady days of Apollo, Mars by 2000 looked entirely feasible. Now we’re talking about the 2030s for manned exploration, and even that target seems to keep receding. In the review that follows, Michael Michaud looks at Louis Friedman’s new book on human spaceflight, which advocates Mars landings but cedes more distant targets to robotics. So how do we reconcile ambitions for human expansion beyond Mars with political and economic constraints? A career diplomat whose service included postings as Counselor for Science, Technology and Environment at U.S. embassies in Paris and Tokyo, and Director of the State Department’s Office of Advanced Technology, Michael is also the author of Contact with Alien Civilizations (Copernicus, 2007). Here he places the debate over manned missions vs. robotics in context, and suggests a remedy for pessimism about an expansive future for Humankind.

by Michael A.G. Michaud

Many people in the space and astronomy communities will know of Louis Friedman, a tireless campaigner for planetary exploration and solar sailing. He was one of the co-founders of the Planetary Society in 1980, with Carl Sagan and Bruce Murray.

In his new book, entitled Human Spaceflight: From Mars to the Stars, Friedman states his argument up front: Humans will become a multi-planet species by going to Mars, but will never travel beyond that planet. Future humans will explore the rest of the universe vicariously through machines and virtual reality.

Friedman acknowledges that public interest in space exploration is still dominated by “human interest.” No one, he writes, is going to discontinue human spaceflight. Yet there is a conundrum. While giving up on manned missions to Mars is politically unacceptable, getting such a program approved and funded is not an achievable political step at this time. If another decade goes by without humans going farther in space, Friedman writes, public interest will likely decline and robotic and virtual exploration technologies will pass us by.

Friedman claims that going beyond Mars with humans is impossible not just physically for the foreseeable future but culturally forever. The long-range future of humankind, he declares, is to extend its presence in the universe virtually with robotic emissaries and artificial intelligence. This argument puts a permanent cap on human expansion, as if travel beyond Mars never will be possible.

Friedman sees having another world as a prudent step to prevent humankind being wiped out by a catastrophe. He argues that the danger of not sending humans to Mars is that we will become complacent. If that complacency overcomes making humankind a multi-planet species, we are doomed.

Friedman dismisses big ideas about exploiting planetary resources throughout the solar system and living everywhere to build civilizations and colonies on other worlds. He can’t see why or how we would do this, nor can he see waiting to do so. This illustrates an old split in the space interest community between those advocating space exploration and those supporting space utilization and eventual human expansion.

In his chapter entitled Stepping Stones to Mars, Friedman lists potential human spaceflight achievements with dates. An appendix presents a plan for a manned Mars mission in the 2040s. That first landing is to be followed later by missions establishing an infrastructure for human habitation, an effort that will take many decades.

Interstellar flight

This book’s subtitle is From Mars to the Stars. Yet Friedman dismisses interstellar travel by human beings as a subject of science fiction. People are too impatient, he writes, to wait for the necessary life-support developments. This contrasts with Carl Sagan’s 1966 comment that efficient interstellar spaceflight to the farthest reaches of our galaxy is a feasible objective for humanity.

Friedman argues that we have only one technology that might someday take our machines to the stars – light sailing. It may be another century before we have large enough laser power sources to drive small unmanned spacecraft over interstellar distances. The barrier of bigness will be overcome by the enablement of smallness.

Friedman suggests three interstellar precursor missions: the first launched in 2018 to the Kuiper Belt and onward to the heliopause; the second launched in 2025 to the solar gravity lens focus and on to 1,000 astronomical units; the third launched in 2040 to the Oort Cloud.

Virtual Reality

Friedman oversells virtual reality just as some others have oversold manned spaceflight. He acknowledges that we have yet to reach full cultural acceptance and satisfaction with the virtual world. Yet he seems to assume that such acceptance by the general population is inevitable.

Calling virtual reality human exploration may confuse many readers. Will we be content to watch all future exploration through robotic eyes?

There may be an unstated reason for preferring virtual reality over human presence. If future space exploration were entirely robotic, scientists would be in charge.

Cautions about Mars

Mars is far from ideal as a future home for humankind. The thin atmosphere is mostly carbon dioxide. Temperatures are low. The surface is more exposed to radiation and meteorites than Earth. Yet Mars remains the best candidate for a second planetary home within our own solar system.

Like other schedules proposed by some space advocates, Friedman’s plan for missions to Mars may be too optimistic. Yet such optimism keeps goals alive and encourages others to get involved.

What seems wildly optimistic now may be possible over the longer term. In the 1950s, some scientists thought that sending humans to the Moon was impossible.

The failure of grand visions

Friedman is correct in stating the biggest problem of space policy: the merging of grand visions with political constraints. In 1988, President Reagan’s statement on space policy included the idea of expanding human activity beyond Earth and into the solar system, an endorsement long sought by some elements of the space interest community. President George H.W. Bush fleshed out this idea in 1989 with his Space Exploration Initiative, urging that the U.S. develop a permanent presence on the Moon and the landing of a human crew on Mars by 2019. These visions failed to win the financing that would make them feasible.

Frustration and Patience

It is understandable that long-time campaigners for further exploration and use of space get frustrated, in some cases foreseeing the end of such endeavors. We all want to see major hopeful events occur in our own lifetimes. Yet we share some responsibility to look beyond.

Writing off human expansion beyond Mars for all the humans who follow us is, despite Friedman’s claim, pessimistic. The remedy is a younger generation of advocates.

A Little History

Friedman states that the settlement of Mars is the rationale for human spaceflight. The leaders of the Planetary Society did not initially support that goal. In the organization’s early years, its chief spokespersons criticized NASA’s emphasis on human missions (particularly the Space Station), which they saw as robbing funds that should have gone into further robotic exploration.

Sagan and others later realized that the planetary exploration budget rose and fell with the rise and fall of manned spaceflight programs. When NASA funding was rising, space science prospered; when NASA funding declined, space science funding declined with it. After the cancellation of further Apollo missions, planetary science was hit hardest by budget cuts . This revived a debate as old as the space program, between advocates of manned spaceflight and those who believe that priority should be given to exploration by unmanned spacecraft.

Friedman wrote in a 1984 article in Aerospace America about extending human civilization to space, suggesting a lunar base, a manned expedition to Mars, or a prospecting journey to some asteroids undertaken by an international team.

By the mid-1980s, the Planetary Society was advocating a joint U.S. Soviet manned mission to Mars. Senator Spark Matsunaga of Hawaii introduced legislation to support this idea and published a book in 1986 entitled The Mars Project: Journeys beyond the Cold War. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev made overtures to the U.S. in 1987 and 1988 for a cooperative program eventually leading to a Mars landing.

Bruce Murray, reacting favorably to the 1989 Space Exploration Initiative, published an article in 1990 entitled Destination Mars—A Manifesto. Observing that the space frontier for the U.S. and the USSR had stagnated a few hundred miles up, Murray commented that neither the United States nor the Soviet Union is likely, by itself, to sustain the decades of effort necessary to reach Mars. Murray urged a joint U.S.-Soviet manned spaceflight program leading eventually to Mars.

This reviewer argued at the 1987 Case for Mars conference that relying on the Soviet Union during the Cold War made such a mission subject to political volatility. This turned out to be true. As Friedman reports, a brief flurry of interest by President Reagan and Gorbachev in a cooperative human mission to Mars disappeared quickly in the face of large global events such as the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

More recently, when the U.S. sought to punish Russia for invading Ukraine, Russian officials made public statements threatening the continuation of Russian transport of Americans to the International Space Station, even though the U.S. was paying for those flights.

References

Louis Friedman, Human Spaceflight: From Mars to the Stars, University of Arizona Press, 2015.

Louis D. Friedman, “New Era of Global Security: Reach for the Stars,” Aerospace America, August 1984, 4.

Michael A.G. Michaud, “Choosing partners for a manned mission to Mars,” Space Policy, February 1988, 12-18.

Chapter entitled “Scientists, Citizens, and Space” in Michael A.G. Michaud, Reaching for the High Frontier: The American Pro-Space Movement, 1972-1984, Praeger, 1986, 187-213.

Bruce Murray, “Destination Mars: A Manifesto,” Nature 345 (17 May 1990), 199-200.

Iosif Shklovskii and Carl Sagan, Intelligent Life in the Universe, Dell, 1966, 449.

@Larry Kennedy,

The USA is way ahead on cutting pollution. China is going to be selling breathable air without a drastic turnaround. Yet, they are building bigger

(aircraft carriers and carrier killer missiles) and faster (next gen stealth jets) weapons that roll of their assembly lines with alarming frequency..

Radiation from the nuclear accident in in Japan has reached our Northwest coast in concentrations that shouldn’t be ignored. Yet, Japan and China are now locked in an arms race over a tiny speck of land in the Pacific. And any thoughts of a joint space mission with China to share the costs of manned Deep Space travel is a non-starter. ATC, we can add the Russians to the list soon enough.

So, if I sound a little alarmist about the misguided use of human and natural resources please keep in mind that ISIS is planning an continuation of assaults that will require us to resort to DNA/phenotype specific biological weapons. Yeah Baby, asymmetric warfare at it’s finest. All it takes is a few more homeland attacks and a willing government (Trump, et al.) to approve the development and unleash such a weapon. And, before you pooh-pooh such a “crazy” weapon, may I remind you of a couple of cities in Japan that were “glassed” by another “crazy” weapon.

If you still think I’m being paranoid then forgive me my excessive pessimism in the face of worldwide political/military/ecological intransigence. The old M.A.D. politics of the Cold War are meaningless when faced with a diabolical enemy who, like us, has no respect for borders or civilian populations.

In the face of the economic and political realities of the FOREVER WAR we have been fighting since WWI, I would be blind to believe that a huge chunk of the war (Defense???) budget will be used to fund any Deep Space missions beyond the current levels. For most politicians the expense of a manned mission beyond LEO is career suicide when their constituents are fearful of a terrorist attack at their local 7/11.

And, considering the nationality of our current enemy, the visa giveaway for overseas brain power will be coming to a screeching halt, despite the financial arm twisting Silicone Vally brings to bear on our government.

IF, we can change our industries in time to lower the cost of energy production and at the same time reduce pollution and increase educational opportunities, we’ll survive. Otherwise, better cell phones and the increasing number of palm-gazing youth have nothing to look forward to besides the next-gen IPhone, most can’t afford, and the new release of Call of Duty.

How about a flag for Mars….

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20151214-what-would-the-flag-of-mars-look-like