It’s the end of an era. On Saturday December 19, the Cassini Saturn orbiter will make its final close pass by Enceladus. This doesn’t mark the end of Cassini itself, which still has work to do especially with regard to Titan, but it does mean the end, at least for now, of our close-up study of a remarkable phenomenon: The plumes of Enceladus, which Cassini itself discovered. We’ve gained priceless data through its flybys, helping us make the case for an internal ocean.

Cassini will continue to observe Enceladus until mission’s end, but only from much greater distances. In fact, as this JPL news release explains, the closest Cassini will come to Enceladus after Saturday is about four times the distance of the upcoming flyby. Nor will the Saturday event be as close a pass as Cassini’s dive through the south polar plume on October 28. That one took the spacecraft within a scant 49 kilometers of the surface, returning data that is still undergoing analysis as we probe the plume’s activity. A key issue: Is there hydrogen gas here, which would offer yet more evidence for active hydrothermal systems on the seafloor?

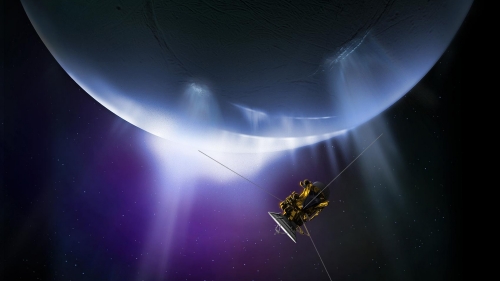

Image: An animation showing the upcoming December 19 flyby of Enceladus, in which Cassini’s composite infrared spectrometer instrument will observe the moon’s south polar terrain. Credit: NASA/JPL.

The Saturday event will be all about measuring the moon’s heat, a critical factor in making sense of the factors driving the spray of particles and gas from the ocean beneath. 5000 kilometers turns out to be about the right distance to allow the best working of Cassini’s Composite Infrared Spectrometer (CIRS) as it maps the heat flow across the southern polar region, according to Mike Flasar, CIRS team lead at NASA GSFC:

“The distance of this flyby is in the sweet spot for us to map the heat coming from within Enceladus — not too close, and not too far away. It allows us to map a good portion of the intriguing south polar region at good resolution.”

Image: An exciting chapter of space exploration history will come to a close as NASA’s Cassini spacecraft makes its final close flyby of Saturn’s active, ocean-bearing moon Enceladus. The spacecraft is scheduled to fly past the icy moon at a distance of 4,999 kilometers on Dec. 19 at 0949 PST (1749 UTC). Although Cassini will continue to observe Enceladus for the remainder of its mission (through Sept. 2017), its next-closest encounter with the moon will be at a distance more than four times farther away. The focus of the Dec. 19 encounter will be on measuring how much heat is coming through the ice from the moon’s interior — an important consideration for understanding what is driving its surprising geyser activity, which Cassini discovered in 2005. Credit: NASA/JPL-CalTech.

Keep in mind that the south polar region of Enceladus was well lit when Cassini arrived at Saturn in 2004, but at present the area is in winter darkness, making these heat studies that much easier to complete absent the heat of the Sun. By mission’s end, we will have data on six years of winter darkness in the south polar area. The discovery of geologic activity caused the mission’s flight plan to be changed to make Enceladus a prime target of operations. Of all the gifts Cassini has given us, finding a global ocean beneath the ice glitters the most brightly.

A collection of new news items on Enceladus, including a report that the geysers are not geysering as much as they were when first detected by Cassini ten years ago:

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn28675-two-missions-face-off-to-seek-life-in-icy-seas-of-enceladus/

http://orbiterchspacenews.blogspot.ch/2015/12/cassini-closes-in-on-enceladus-one-last.html

http://www.space.com/31385-saturn-moon-enceladus-geysers-losing-steam.html

http://www.airspacemag.com/daily-planet/searching-life-enceladus-180957564/

I was wondering about that. I know it takes a while for it to transmit data back here, but it still seemed odd that we hadn’t gotten any preliminary information on what it found in the geyser.

The regions near the geysers of Enceladus look like they might hold a

thin semi permanent regional ice/water vapor atmosphere. If is so then maybe designing space craft to explore the region which takes advantage of this might be a good idea. The gravity is so feeble at 1.1 % of earth that it would not take much lift to keep a sizeable craft aloft. For example. what about a probe that uses a helicopter like architecture

i.e.(blades push against the thin ‘MIST’ of the moon)

It would take a fair amount of fuel to brake the craft into proper position, and care must be taken it doesn’t get taken by Saturn’s massive Gs during the maneuver. It if was feasible, maybe you could even attach instrument package to a spool and cable system which is used to lower down to the surface or even under an exposed body of water.

I think the main problem would be icing-up of the helicopter blades from the ‘mist’ in that extremely low temperature. I doubt if it would stay up for long.

I wonder if the pressure at the surface would be anywhere near bouyant enough for some gossamer-like balloon instead of rotors?

I like the idea of dispersing several small autonomous ‘crawlers’ all around the vent mouths along a section of tiger-stripe… they could maybe crawl down a vent some ways to access pristine material on its way out to the surface. Maybe oneday?

Brett: There was some VERY INTERESTING DATA released earlier this week! The PH value of the subserface ocean appears to be VERY HIGH, but NOT high enough to be DETRIMENTAL to life as we know it! In other words, chemical reactions between the alkaline ocean and salts in the ocean would produce MORE THAN ENOUGH ENERGY for life to sustain itself! A particularly interesting possibility as a result of this could be the production if METHYL MERCAPTAN as life forms die and DECOMPOSE! CH3SH would be an ALMOST CERTAIN BIOMARKER, because it can only be produced IN AMOUNTS LARGE ENOUGH TO BE DETECTABLE by Cassini’s instruments as a RESULT of BIOLOGICAL processes! Cassini cannot detect life DIRECTLY, but an unusually HIGH concentration of methyl mercaptan(which Cassini CAN detect) would be an EXTREMELY STRONG indirect detection! I’ve been waiting for YEARS for the October 28 encounter FOR JUST THIS REASON! Unfortunately, it will be months(or YEARS, if CH3SH IS detected) before the FINAL RESULTS are published.

Re: icing of rotor blades:

Earth helicopters operating in the arctic regions, use de-icing mats.

But your point is taken because it would be much colder than any arctic environment above those geysers, an therefore would require a large supply of power to keep the blades from freezing.

Harry R. R.

Crawlers might work, but they might need to be of the Six legged design.

Footing could only be assured if as each leg moves forward it tips melt the

ice a bit then the freeze out gives grip. Melt-Ice-Melt pattern would be a slow mover though. but a much steadier one.

A hopper design may work quite well in the low gravity environment, there are many materials that can undergo a rapid shape change due to an electrical current that would give enough impulse to roam the surface without the need for complicated moving part designs which could go wrong.

Michael has a good point. In low gravity, hopping may be a much better way to roam than driving on wheels. I don’t think there is enough gas there for anything aerodynamic like rotors or wings.

I imagine a three legged design with feet pointing down and knees pointing up. The feet are normally used for sitting and hopping, but if the craft accidentally ends out upside-down (feet up, knees down), the knees can be used to hop back into the correct orientation.