I first encountered Michael Chorost in his fine book World Wide Mind (Free Press, 2011), which looks at the relationship between biology and the machine tools that can enhance it. Mike’s thinking on SETI has already produced rich discussion in these pages (see, for example, SETI: Contact and Enigma). In today’s essay, he’s asking for reader reactions to the provocative ideas on insect memory and intelligence that will inform his next book. While it does not happen on Earth, can evolution invent — somewhere — a social insect society capable of long-term memory and civilization? A nearby planet evidently hostile to our kind of life offers fertile ground for speculation.

by Michael Chorost

I’ve admired Paul Gilster’s Centauri Dreams for many months and I’ve always been impressed by the quality of the comments. Paul graciously allowed me to write a guest entry to test one of my book-in-progress’s ideas on a smart audience — you.

This book-in-progress will be my third book. My first two books were about bionics and neuroengineering, respectively titled Rebuilt (Houghton Mifflin, 2005) and World Wide Mind (Free Press, 2011.) I’ve also published in Wired, New Scientist, Slate, Technology Review, the Chronicle of Higher Education, and Astronomy Now.

The book is about communication with extraterrestrials. Not by radio but in person, with us visiting their planet and looking at their mugs (or whatever they have instead of mugs). How should we begin trying to communicate? What could we safely assume — and not assume — about how minds think? What knowledge could we bring to bear from evolutionary theory, linguistics, cognitive science, and computer science?

Of course, direct contact anytime soon is unlikely in the extreme. That’s why, below the surface, the book is about a deeper set of issues: What are the universals of thought and language? Can intelligent minds be so different as to render communication impossible? What kinds of advanced cognition can an evolutionary process invent? The book gets at these ideas by using alien communication as a vehicle.

So here’s the idea I want to test on you all. I asked myself, “Would it be possible for social insect colonies on some other planet to evolve to have language and technology – in other words, a civilization?”

Of course, the idea of swarm intelligence, or hive-mind intelligence, has been around forever in science fiction. To give but one example, Frank Schatzing’s The Swarm posits an undersea alien made of single-celled, physically unconnected organisms that collectively have considerable intelligence. But I need to examine the idea with much more rigor than can be done in fiction.

I refined the question by deciding that, as on earth, the individual insects would have brains too small for serious cognition. The unit of analysis would not be individual bugs but colonies of bugs. The intelligence would have to emerge from their interaction.

After much thought, my answer to the question is “No – but…”

Let me explain both the No and the but. It is these explanations on which I want your feedback.

To start with the No. I don’t think it’s possible for physically separate units to form a collective that supports high intelligence. The reason is straightforward: physically disconnected units have no way of permanently storing large amounts of discrete information in a way that is available to the collective. More succinctly, they can’t support long-term memory.

Of course, information can be manipulated by collectives even when the units have no permanent connections among them. If you’ve read Douglas Hofstadter’s “Ant Fugue” you know how ant colonies collectively find and consume food. A forager comes across food and lays a pheromone trail while returning to the nest. Other workers follow that trail and lay down pheromones of their own. When the food is gone the returning ants stop emitting pheromones, and the ants move on to other things. From a global perspective it looks as if the colony has a “memory” of the food source. Insect colonies have many mechanisms of this sort, which go under names like “stigmergy” and “quorum sensing.” They are brilliantly described in the literature, especially by Thomas Seeley. [1] But all of them yield only short-term memory. As soon as the insects disperse and the pheromone evaporates, the information vanishes.

That is a problem, because language and other forms of advanced cognition need long-term memory. Language requires storing a large number of primitives (e.g. words) plus state information related to a conversation (the identity of the interlocutor, the situation, information about past and future, and so forth.) Not only that, the method of storage has to be both stable and easily changeable. If it can’t be changed, an intelligence can’t keep up with changing events in the world.

Let me pause here to define what I mean by “intelligence” and “language.”

I like the definition of intelligence offered by Luke Muehlhauser in his book Facing The Intelligence Explosion. [2] He defines it as “efficient cross-domain optimization.” Cross-domain optimization refers to being able to exercise intelligence in multiple domains. Consider that IBM’s Deep Blue program is very smart at chess but can’t play checkers, let alone want to learn how. It has intelligence in one domain, and only one. Or take honeybees, who are outstanding at communicating the location of food but have no way of asking humans to move that food closer, or change it. In order to cross domains a mind needs not just cognition but metacognition, the ability to think about thinking. When I speak of intelligence I mean the kind that can reflect upon its own actions, make plans, describe things that don’t exist, and so forth. This is the kind of intelligence that is required to build a civilization.

Now language. I like Steven Pinker’s definition of it: Language is a finite set of primitives that when combined yield an infinite number of possible statements. [3] By this definition, language is open-ended. It can be used to say anything. Contrast that to, say, referee signals in baseball. They are a communication system but not a language. A referee can precisely say whether a pitch is a ball or strike, but he can’t use the repertoire of signs to talk about taxes, or explain that the pitcher has just become a free agent. Likewise, a honeybee can precisely state where food is but can’t use its waggle dance to discuss the weather with a human. Animals such as honeybees, birds, chimps, dolphins, parrots, and dogs all have communications systems, some of which are very sophisticated, but they are closed-ended; they do not rise to the level of language.

Now that I have defined intelligence and language, please note that both of them simply have to have long-term memory. Without long-term memory, no intelligence, no language. And I don’t think there is any way at all that a social insect colony can get long-term memory if its units are physically disconnected. It has no physical medium in which it can store information in a way that is both permanent and easily changed.

So, Conclusion A: Social insect colonies do not have the memory mechanisms to support language, therefore no bug civilizations.

Now let’s get to the “but.” After working out Conclusion A I asked myself, “Could insect colonies acquire, through an evolutionary process, a mechanism of long-term memory?” I think the answer to that question is yes.

Consider how mammalian brains store long-term memory: in collections of synapses. A synapse is a physical gap between the axon of one neuron and the dendrite of another. Depending on the strength of an incoming signal and the synapse’s threshold, neurotransmitters either flood into that gap or they don’t. If they do, they are picked up – essentially “smelled” – by chemoreceptors on the dendrite’s side. Then the signal continues to the body of the next neuron, which uses it as an input for its own decision-making process.

Each neuron in a mammalian brain has thousands of synaptic connections to other neurons – it is part of an immense network of physically connected units. By changing synaptic configurations and thresholds, neurons can encode immense amounts of discrete information. That information is both stable and easily changeable.

So for an insect colony to gain long-term memory, it has to invent the equivalent of the synapse. Not in the brains of individual insects – they already have plenty – but on the level of the colony as a whole, using interactions between insects.

This is obviously tricky because insects move around. But there are insects in colonies that don’t move around: the larvae. Even better, in flying insect colonies they are generally stored in honeycombs that keep them in place. And better still, they’re loaded with chemoreceptors. The ends of antennae and feet are the “noses” by which insects pick up smells.

Imagine, then, the antennae and feet of developing larvae thrusting their way through the waxen walls of honeycombs and making contact with the antennae and feet of their neighbors. Right there you have the basic elements of synaptic connections. If the larvae can send signals and adjust synaptic thresholds, they could form a network.

Of course, there has to be an evolutionary reason why such a network would ever come into being. There would have to be accidental variations that create primitive networks, and they would have to confer fitness and reproduction benefits.

So consider this story of an evolutionary process. It so happens that in some kinds of colonies, the larvae perform a digestive function for the colony. The workers bring them the food that they can’t digest, and the larvae break them down into compounds the workers can eat. [4] So the larvae are effectively the colony’s stomach. The food needs of workers vary depending on temperature and season and so forth. Larvae that could exchange information with other larvae about digestion could produce better food, and that benefit would tend to be conserved and amplified. Over many generations, then, colonial stomachs could evolve into colonial brains. Each larva would be a large neuron with many connections to other larvae, and the synaptic configurations between them would store long-term memories.

This is, of course, a just-so story – but then evolution is full of just-so stories of evolutionary adaptations that seem spectacularly improbable. For example, insect wings are thought to be adapted legs. [5] And insects have often evolved to look like leaves and twigs for camouflage. Nature is astonishingly inventive at reshuffling its building blocks. I am not trying to convince you that my larvae-to-brains story is likely, only that it is possible.

There is one more piece to the puzzle. Long-term memory is metabolically and spatially expensive. Clearly, on Earth insect colonies have seen no need to develop it; they’ve done well for millions of years without it. So you need to have an environment in which it would confer fitness advantages.

Consider the planet GJ832c.

GJ832c is a rocky planet of 5.4 Earth masses orbiting a red dwarf star sixteen light-years away. Happily, it’s in the star’s habitable zone. Since a red dwarf is very dim the habitable zone has to be very close to it, and accordingly GJ832c has a year just 36 days long. [6]

We don’t know much about GJ832c. We don’t know its density, so we don’t know its surface gravity. But I’ve guessed that it’s 78% as dense as Earth, which would give it a surface gravity of 1.5 gees. We don’t know its rotational period, but since it’s so close to its star it would probably be gravitationally locked. Mercury has a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance, which means that it rotates three times every two years. So let’s say that GJ832c also has a 3:2 spin-orbit resonance.

We don’t know its axial tilt, but gravitational locking tends to stabilize axial tilt near zero – Mercury’s is just two degrees, and the Moon’s is 6.6 degrees, compared to the Earth’s 23 degrees. So let’s say its axial tilt is zero. But we do know its orbital eccentricity, .18, which is very eccentric by our solar system’s standards.

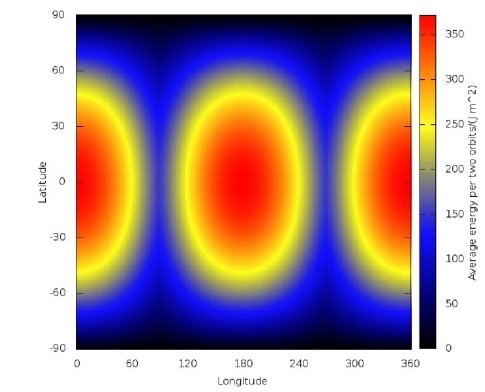

If you put these facts and guesses together you can compute how much solar exposure each point on such a planet gets, like so:

Astonishingly, on such a planet the climate is determined as much by longitude as latitude. Yes, longitude. Some longitudes are in daylight for long periods, while other longitudes never see the sun at all – including a few points on the equator. The planet looks like a tennis ball with burns on opposite sides (red), a temperate zone ringing the burns (yellow), and ice everywhere else (blue). [7]

To be sure, the temperature extremes would be moderated by the atmosphere. My guess is that you would see Hadley cells centered on the hot zones, since the hot air would rise and cold air would come in underneath it. Since the planet rotates so slowly, you wouldn’t see much Coriolis force to shear the atmosphere sideways. So there would probably be steady winds moving toward the center of each hot zone, distributing heat between the zones.

Note, however, that only one “hot” end can face the star at any given moment. The center of each hot zone would face the star continuously for blistering days on end, and then suffer a long night. (I haven’t worked out what the day-night cycle would look like on various points of the planet. Perhaps the temperate zones would be in continuous but relatively soft illumination. For this I need the help of someone who specializes in orbital dynamics.)

In any case, GJ832c would be a nasty planet. It’d have high gravity, temperature extremes, constant wind, and possibly a thick atmosphere and ultraviolet flares from its star. I don’t think you would get large-brained mammals here simply because of the gravity: blood circulation and locomotion would be expensive. Predator actions like leaping and throwing things would be difficult. So would prey defenses like running and climbing.

What would flourish here? Bugs. Bugs are modular, tough, and cheap. They are small enough to be relatively unaffected by gravity, and their chitinous exoskeletons would be relatively impervious to UV flares.

So let’s say that social insect colonies evolve in the temperate zone. But the temperate zone is exceedingly narrow, perhaps just a few hundred miles across. Sooner or later population pressures are going to drive new colonies into the hot and cold zones. There, new colonies could find resources that aren’t in the temperate zone, say particular kinds of hothouse flowers, lichens, and fungi. And they would face new scarcities too, say of water.

On GJ832c, colonies that learned to trade resources across zones would have an enormous survival advantage. Water for nectar, nectar for fungus, and so on. Insects on Earth have signaling mechanisms that could be adapted to manage such trades. For example, they engage in territorial displays in which soldiers posture at the borders between colonies, inflating their limbs to seem more threatening, while “head-counting” ants on each side carry information about the enemy back to the nest. (They probably don’t actually count the soldiers using numerals; more likely they sense the rate of encounters with them.) [8] Such signaling mechanisms could be adapted to convey information for economic exchanges. Colonial brains would store such information, remembering who traded what and for how much. Over many generations, such signaling systems could evolve into language.

You may wonder about tools, since tools have fundamentally shaped the development of language in humans. For brevity’s sake I won’t go into it here, but I’ve worked out how insect colonies could ignite fire, forge metals, and use tools; again, I’ve extrapolated from things social insects do on Earth. With language and tools a species is just a few hops, skips, and jumps away from having a full-fledged civilization.

This doesn’t mean they would think like humans, of course. They would have networks that can support long-term memory, but those networks would have a very different organization and would support very different kinds of physical needs. In the manuscript I discuss the role of simulation and embodied cognition on the development of language.

So, Conclusion B: With the right environmental pressures, social insects could develop long-term memory, language, tool use, and a civilization.

Again, I am not arguing that this is likely, only that it is possible. What do you think? Am I correct in thinking it is possible, or is there something fundamental that I am neglecting?

I’m asking you to put pressure on these ideas. To look for their weak spots. But I would also appreciate it if, for each weak spot, you could suggest a solution, if you can think of one.

Many thanks in advance for your comments and ideas.

——-

Footnotes

1. Seeley, Thomas (2010). Honeybee Democracy, Princeton.

2. Muehlhauser, Luke (2013). Facing The Intelligence Explosion. Machine Intelligence Research Institute. Kindle location 655.

3. Pinker, Steven (2007.) The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates Language. Harper Perennial, p. 75.

4. Masuko, Keiichi (1986). “Larval hemolymph feeding: a nondestructive parental cannibalism in the primitive ant Amblyopone silvestrii Wheeler (Hymenoptera: Formicidae).” Behav Ecol Sociobiol 19: 249-255. See also http://blog.wildaboutants.com/2010/06/21/question-1-ant-digestion/.

5. Carroll, Sean (2006). Endless Forms Most Beautiful: The New Science of Evo Devo. Norton, p. 176.

6. Planetary Habitability Laboratory data for GJ832c, http://www.hpcf.upr.edu/~abel/phl/hec_plots/hec_orbit/hec_orbit_GJ_832_c.png

7. Brown et al. (2014). “Photosynthetic Potential of Planets in 3:2 Spin Orbit Resonances.” International Journal of Astrobiology 13:4 (279-289). Page 284. I’ve used the figure computed for an eccentricity of 0.2, which I figure is close enough.

8. Hölldobler, B., and Wilson E. O. (2008). The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies. New York: W. W. Norton, p. 306.

Alien intelligences could be like the Chtorr, which is essentially social insects extended to include the entire bio-sphere of species.

Immune systems contain long term memory, so in principle, LTM can be encoded as DNA sequences, rather than synaptic strength. Enough for a language and grammar? I don’t know, but I wouldn’t rule it out.

The insects do not have to be static or even connected to create a synaptic network. By recognizing unique insects, either by sight or chemical encoding, any insects can preferentially connect with any other. The frequency being the “synaptic strength”. Even in computers programs of neural networks, the network layout isn’t actually stored the way we visualize it. I see no reason why uniquely addressable individuals and their communication frequencies with specific other individuals cannot be an effect NN.

Regarding trading. I see no reason why this isn’t a basic optimization problem that5 can be mindless. Human trading is very much local, yet the system as a whole optimizes. This is how markets work, and we know human financial traders are not so smart, nor have long term memories.

Tool using is possible even with simple insect colonies. We also know that ants and termites can “farm” aphids and fungi in a way that is recognizable as human farming.

If you consider organizations of humans as a similar mapping as insect colonies, I see no a priori reason why insect colonies, as equivalent to minds, could not interact as if in an organization and achieve more sophisticated behaviors, that we might call civilization.

Interesting post. I think are other aspects to the creation of a civilization — diversity and creativity — that don’t necessarily appear in a hive mind. To me a hive mind is very much like a supercomputer, filled with lots of data. It’s what you do with that data that’s important. The great geniuses of our race have often had to create working against the conventional wisdom. Galileo and Einstein are prime examples. We can see some of this in a limited form in the number of patents granted in free societies vs those in stratified ones. The freedom to explore and follow a crazy idea that makes no sense but turns out to be valid I don’t see occurring in a hive mind. The only way civilization might occur is that old saw that if a million monkeys typed on a million typewriters for a million years statistics state that at some time they will produce the complete works of Shakespeare. Not the foundation to build a civilization.

Imagine if you will the squid with its chemoreceptors combined with a physical neurotransmitter connected to another squid I.E the two squid could actually use their tentacles to link their nervous systems.

This would evolve through sex as some squid display complex patterns of chemoreception combined with visual chromatophore communication.

http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a222648.pdf

social Insect reproduction as we know it on earth involves reproduction by the one or the few and the sexual evolution of my proposed neural connectivity would not evolve among the haplodiploidy of the eusocial insects.

Our world eons ago had for a while a high oxygen atmosphere in which very large insects evolved it’s this perhaps that would enable the evolution of larger brains,so it’s no accident that larger brains did evolve among the cephalopods as the water medium allows for a greater oxygen exchange.

larger insects in a high Oxygen world would still have to overcome the haplodiploidy barrier to evolving sexualy inabling neuroconnectivity between individuals.

Evolution does not plan anything so what would be required to transfer large amounts of information between neurologically connected beings and what would be the environmental factors that would favor evolving this?

http://yellowdragonblog.com/2015/12/31/evolution-of-mind-in-eusocial-insects-or-mullocs/

Interesting stuff. How possible is it for organisms to develop biological radio communication? Consider that there is life on earth that can sense the direction of earth’s magnetic field, and some can use electromagnetic sensing to detect nearby life. It seems biologically feasible for life to develop means for emissions as well as sensing means. Bioluminesence, generation of current … Why not a biological radiating antenna? Organisms able to signal each other with greater speed than the chemical processes of a brain could potentially be smarter as a swarm than an individual organism, and could function as a whole in real time, given sufficient time to evolve.

Michael,

This is a fascinating essay, and I’m saving this in my reference file (I’m a CG artist and technical writer with a long-time love of science and science fiction.)

Here’s an idea I had while reading your essay. Just as bees communicate with “dances,” what if an ant-like species could lay down pheromone trails within their own nests that formed patterns with meaning? In short, they’re “writing” characters which could be maintained by “scribes” who occasionally refresh, annotate or “erase” the patterns (perhaps with a different type of “null” pheromone.) “Reading” the information would be not-unlike walking the labyrinth at Chartres Cathedral, and an army of scribes over generations could be responsible for remembering their own small sections of the entire encyclopedia — no one “ant” would have to memorize the entire thing. It’s basically decentralized biological “cloud” storage.

If the entire pattern/history of the colony had to be reproduced elsewhere because of an ecological catastrophe (flooding of the nest, or they simply need to move elsewhere), then each scribe ant would be responsible for reproducing their own section, and “overlap” of memorized sections among many scribes would help them create the whole, without gaps.

So… that’s my science-fiction concept for today. Thanks for your essay, and for reading my thoughts!

‘Insect memory and intelligence that will inform his next book. While it does not happen on Earth, can evolution invent — somewhere — a social insect society capable of long-term memory and civilization? A nearby planet evidently hostile to our kind of life offers fertile ground for speculation.’

I believe what holds back our insects on our planet is their oxygen extraction system or they very well could have developed higher intelligence. There has been in the past an example of large insects so size is not a huge issue.

http://voices.nationalgeographic.com/files/2009/02/giant-sea-scorpion-425×446.jpg

‘How should we begin trying to communicate?’

Light(gestures), electrostatic (charges), sound (vibrations) and smells (chemicals) are the only ways I can think of communicating with. Light has the huge advantage of speed and distance over the other forms of communication so a well developed visual system would be a distinct advantage. We would need to monitor the insects reactions to various stimuli and perhaps use lasers (invisible) to identify certain chemicals that are emitted and sort of connect the association with each to perhaps understand their ‘sensory’ language. I would caution on chemical communication without knowing the effect as they could inadvertently damage the organism.

The entire human being is not dedicated to intelligence but each cell plays its part, I can see no obstacle to large macro structures storing information for instance larva sags but getting the information out again in a timely manner could be an issue.

‘After much thought, my answer to the question is “No – but…”’

Life has a remarkable way of getting around obstacles.

‘And I don’t think there is any way at all that a social insect colony can get long-term memory if its units are physically disconnected. It has no physical medium in which it can store information in a way that is both permanent and easily changed.’

The hard shell of the insect could be used to store information such as words, visual, or in grooves that could be once strung make a sound like a gramophone record. Nothing stops them using mud to form shapes and signs as well so we can’t say no on that front.

‘Yes, longitude. Some longitudes are in daylight for long periods, while other longitudes never see the sun at all – including a few points on the equator.’

The equator should have illumination as normal and no dark spots.

‘Since the planet rotates so slowly, you wouldn’t see much Coriolis force to shear the atmosphere sideways.’

Due to the high orbital velocity (36 day orbit) I would think there would be a Coriolis effect but not as pronounced as on Earth.

‘I haven’t worked out what the day-night cycle would look like on various points of the planet. Perhaps the temperate zones would be in continuous but relatively soft illumination. For this I need the help of someone who specializes in orbital dynamics.)’

A dense atmosphere perhaps with dust due to constant winds would create a large twilight zone over the terminator.

‘I don’t think you would get large-brained mammals here simply because of the gravity: blood circulation and locomotion would be expensive.’

A dense atmosphere acts in a supportive manner much like water so large creatures are possible. If they are smart they can move about as the planet spins so slowly walking/flying could keep them in constant daylight.

A better ‘Mercury’ temperature map me thinks!, set up a nice magnetic field and we have another home, but don’t get me started! Just mentally adjust the temperature colour for a new temperature range.

http://diviner.ucla.edu/mercury/posters/Poster-04/poster-04.html

Have a Happy New Year Paul and all C.D readers.

The following is a little rambling. So, sorry for that. Anyway, I’ve only begun reading your appeal for ideas, yet I’d like to remark that while I greatly respect your goal of creating a believable truely alien civilization, there still seems, despite your efforts to create a conceptual commonality amongst all (theorized) civilisations, perhaps still a degree of anthropocentricity in your musings. For example, I take issue with the commonly expressed assumption that long term durable yet changable memory storage is necessary for a civilization. I can even imagine a civilisation without a symantics system in a standard form. Consider a sort of extremely rapid and flexible sort of evolutionary process. I’ll take your hive format if you like. I can at least vaguely imagine a collective with essentially only one single goal. A goal that is of such a nature that a civilisation of sorts could arise from it purely on the basis of a biological imperative. The key here would be to identify that imperative. A singular impulse from which a primitive society could ascend to even a tool wielding (assuming the anatomical prerequisites exist) technological one. Instinctively. With an unbelievably complex and multifaceted pheromonal communications system for example. Perhaps the creatures are capable of synthesizing ever new chemical markers to identify, mark and direct. This may allow a more rapid evolutionary process than we are familiar with on earth. As one can see in a simpler fshion amongst many species here a singular goal obviously does not preclude diversification of task objectives amongst individual group members. The key as I stated is creating a particular, a very special type of overarching imperative. A single instinctual commandment. An ecosystem that developed widespread pheromonal communications of the self adapting selfsynthetizing sort amongst many species could lead to a dominant species that dwarfed all others in its mastery of the pheromonal manipulation. Perhaps even at some point coopting the lesser species’ systems. Domination of the ecosystem. Manipulation of the environment. Optimization could lead to tool manufacture and an enormous advance in complexity. No symantics. No durable memory. Yet, identifiably technological and flexible. Without a master brain. A flight of fancy, I admit.

Let’s unpack this. What is the question we are really asking when we say we’d like to “communicate with extraterrestrials”?

When we first encounter extraterrestrial life, the struggle will be with our definition of life. When we first encounter extraterrestrial intelligence, the struggle will also be with definitions.

Today we are not sure if viruses or prions are alive or not; how then will we apply our anthropocentrism to whatever thrives on Titan’s lakes?

Today, do we “communicate” with whales? With ant colonies? Or are we content to merely learn from them? If we found some sort of interesting processes on another world, I hope we drop our “Star Trek” fantasies (e.g. humanoids who conveniently speak English) and be prepared to learn from whatever we encounter.

We need to lose our anthropocentrism and objectively look at what is out there, rather than search for a civilization, life, an Earth that is like our own. Otherwise we are creating a bias as large as the knowable universe.

@Michael The hard shell of the insect could be used to store information such as words, visual, or in grooves that could be once strung make a sound like a gramophone record. Nothing stops them using mud to form shapes and signs as well so we can’t say no on that front.

You make a very good point. There is no reason why such insects could not use their “extended phenotype” to store information, as we do with clay tablets. books, etc. Just as we no longer rely on memory for long term information storage, especially information that must be stored and retrieved with high fidelity, the insects could do the same. As terrestrial insects can manipulate cellulose (e.g. paper wasps) I see no reason why paper as a storage medium couldn’t be created quite easily with a minimum of technology input.

I would add touch as another communication mode. Blind humans use symbolically encoded characters (Braille) to store and retrieve character information. As another commentator mentioned, a pattern of tunnels in s structure communicated by touch could also serve as information storage.

Terrestrial insects have relatively stereotyped behaviors, “hard coded” into their brains, resulting in a relatively small behavioral repertoire. But so do computers. It would be fascinating to consider an insect acting like a computer or more visually like a classic Turing machine with a paper tape, where its behavior could be determined by the stored information to extend its limited innate behaviors and memory.

Imagine terrestrial bees recording their dances over time, and using that information directly after a few years to best guess where a particular food source was to be found reliably at a certain time of year.

@TLDR – We can communicate crudely with whales, especially dolphins. It is more like pidgin English, but it is two way communication albeit with different methods of interpretation on each side.

It may be that we can only communicate with ETIs that have minds that we can relate to. (c.f. Stanislaw Lem’s “His Master’s Voice”). Some ETIs, and certainly many life forms, will be too alien for us to comprehend. As you suggest, we cannot communicate with almost all terrestrial life, and even with our closest relative, the Bonobo, we can barely hold much of a conversation. To communicate with ETs, they will need to be at some sort of equivalent level of intellectual sophistication as us. Too little and the conversation will be too narrow and limited. Too much and they might find us too limited and not worth communicating with. It wouldn’t surprise me that humans a millennium from now might find us too primitive and simple to be worth communicating with.

‘ As soon as the insects disperse and the pheromone evaporates, the information vanishes.’

I have to take issue with this, as my direct observation of Little Black Ants in my living room and kitchen over a period of 10 years refutes it. In July 2011, ahead of the approach of a severe storm, most of the colony gathered on my kitchen counter in a large circle in what can only be described as a conference. In human terms, they were collectively deciding what to do and where to go. There were scouts running around, searching for food particles, but 99% of the nest was in that circle.

During another storm which was a heavy downpour that was drowning the nest, the LBAs came in through the space between my front door and the doorjamb carrying the unhatched ant eggs, tracking in large, long lines across the living room to my kitchen, invading food sources that were not securely sealed. There were several lines of them attempting to set up nest sites for the unhatched eggs.

And yes, I have wiped away those pheromone trails with household cleanser. It does not matter what I do. The knowledge is passed from one LBA to the rest so that any of them can invade my space looking for food sources.

On other occasions, they have invaded my mailbox in large numbers with unhatched eggs, occupied a portion of a storage bench that contained bags of birdfood, and invaded a large planter filled with parsley seeds, setting up housekeeping directly at a food source. They also invaded my flowerbed, removed all the seeds I had planted and stored them.

To say that ants have no memory beyond the immediate pheromone trail is a false statement which shows a lack of observation. Since ants and other insects have short lifespans, the memory is obviously generational, passed from one hatching to the next continuously.

Wasps also have long term memory. An apple tree next door to me was briefly the home of wasps, until the owner destroyed the nest, five years ago. For the next four years after that, I also destroyed partially completed nests under the railings on my front steps. One or two wasps will attempt every spring to reconstruct those nests. This is a generational memory, also.

I also find that carpenter bees, which will chase off insects that they consider enemies, have the same memory passed from one generation to the next.

To say that this does not happen or does not exist shows a lack of direct observation over a long period of time. I’ve lived here for over 10 years now and can confirm these activities.

It’s also incorrect to use only domestic honeybees as an example of seeking-and-reporting food sources. There are many, many species of bees with which most people are unfamiliar, such as halictid bees, bumblebees and robber bees. The observations have to include the behaviors of all species of bees to draw a conclusion, especially since domestic and wildflowers all move from one area to another over time and the species that I mentioned are not domestic. They are wild or feral bees.

My observations of Little Black Ants are direct and cover a prolonged period, and I can add that they still find their way into my kitchen and living room two to three days ahead of a storm of any kind. The higher the number that appear, the more severe the storm is likely to be, and this includes both winter and summer seasons. To label this activity a ‘hive mind’ is disingenuous and shows a lack of understanding of insects in general.

Since I’m discussing ants, army ants are well-known to form bridges to allow the entire colony or nest to cross a river. They will also form a floating raft to move faster to a new colony site. When they do this, they are looking for new food sources, and for that reason, they send out scouts. I would hardly call this a hive mind. It is closer to a cooperative mind for the survival of the colony.

Interesting essay, thank you. :)

To the question: “Can intelligent minds be so different as to render communication impossible” My reply is a tentative yes.

We have examples on our own planet, there’s several species of animals that show very intelligent behavior and have a complex set of sounds.

Recordings that have been made have so far eluded our attempts to figure out the meaning – if there are any. There’s many recordings of the infrasounds from elephants, whale songs, and ultrasound for dolphins.

(The squeaky sounds in our hearing range is nothing but their sonar. We sometimes interact, humans in distress have been helped by dolphins or that dolphin that approached a diver to have a fishing hook removed. It knew what it was doing there, quite obvious.)

But despite intensive studies, we know very little of what they tell each other, or in fact if it’s a language or just very complex set of call-sounds.

Some birds, Corvidae, have been shown to have remarkably intelligent behavior and problem solving. One in this family of birds (not one studied for intelligence) sometimes use a remarkably complex set of sounds. This is a species of Jay which is very curious and might also use unusual sounds when approaching a human. We don’t even know if it is in the process of developing a language, if it have learned its a good idea to use ‘soothing sounds’ so it will not be attacked or shooed away.

But it have been noted that there can be quite a variation and it might use a new set when it comes close to investigate what the same humans are up to.

So in short, we do not know if this Jay have a simple language or not, even less have we found out what each sound might mean either.

To summarize, we have so far failed to learn the ‘languages’ of beings on our own planet, and considering that we’ve coexisted for many thousands of years sharing both a biological, and historical heritage – we remain complete strangers to each other.

So I tend to think that one intelligent being from a completely different environment, lets say a gasbag living in a gas giant planet, a metallic being on a hot Mercury world, perhaps even a flatlander on the surface of a neutron star, or one slowmoving ice being living in temperatures and chemistry similar to Titan, very well might be so different that there cannot ever be a meeting of minds.

And that even though they might show obvious intelligence and even have a civilization.

The idea of intelligent insect colonies is not new, it have turned up in scifi many times. But yes, individuals in an insect colony on Earth are too shortlived and without actual parenthood there’s no transfer of knowledge, but if a species of long lived insects exist elsewhere they might take the leap if they develop something analog to a library – lets say it gets managed by the queen or drones. This might be the needed stepping stone that could launch them onto the path to build an actual society.

Beside the hive living insects we can find interesting behavior among some dragonflies. Even though they have a minuscule brain, that hardly have space for any cognitive ability. Some dragonflies on Earth investigate anything new that turn up in their habitat. Normally one would think that anything new would potentially be a risk to such a fragile being, and that they rather should avoid anything such.

But instead they show curiosity and try to investigate it, also by landing to take a closer look. Why they do so is a complete mystery, also what biological and evolutionary mechanism that have given them this trait which does not serve any obvious purpose such as for breeding or finding food.

This could be a trait that insect-type life would have good need for if they find themselves in one environment that would favor them to build a society. Curiosity is indeed the foundation of any scientific exploration.

The evolutionary path from a simple insect to an intelligent creature is so long and so convoluted that I would be surprised that there would be any surviving resemblance between the two other than at a deep genetic level and (subdued) phenotype expression. That is, about the same resemblance you would find between humans and fish.

But they might still enjoy dancing. Happy new year.

For a species that uses science and technology, there is an argument that convergent evolution will shape minds so that they have enough commonality to communicate. If this view is correct, then I think we may have a shot at communicating with ETI, at least those not too far intellectually apart. However we know that the likelihood is that and ETI is likely to be millions of years more advanced than us, so we might not have much to say to each other. OTOH, it is also possible that some sort of human transcendence will elevate our minds to a level that may meet other intelligences, especially if there is some sort of intelligence and knowledge limits, preventing unending increases.

Hi Michael,

I enjoyed this post, and I like the thrust of your idea. I’ve got some comments that may be of interest concerning the details of a few points:

“I like the definition of intelligence offered by Luke Muehlhauser in his book Facing The Intelligence Explosion. [2] He defines it as “efficient cross-domain optimization.” Cross-domain optimization refers to being able to exercise intelligence in multiple domains.”

This seems more a criterion of intelligent behavior than a workable definition of intelligence. If intelligence is defined as cross-domain optimization, and cross-domain optimization appeals to the exercise of intelligence, you’ve got a circularity on your hands.

Let’s set that aside for now, and instead say that we can cash out “cross-domain optimization” without appealing to intelligence per se. The wording seems to suggest something along the lines of a problem-solving capability, one with a generalized application, as your examples suggest. I think the remainder of the paragraph on self-reflection, future planning, etc., gets this, but I did want to point out a possible conceptual tangle in the making.

On other point worth mentioning under the intelligence subheading: “In order to cross domains a mind needs not just cognition but metacognition, the ability to think about thinking.”

I think this is true under a certain description, but that description may be favoring an anthropocentric viewpoint “from the inside” as it were. We tend to give a lot of weight to our conscious, deliberative, and discursive reasoning powers, for good reason. When viewed “from the outside” — in the terms available to a third-party scientific perspective — this standpoint may be too “intellectualizing”. By this I mean that much of our cognition may be explicable in terms of sub-personal and non-conscious processes going on beneath conscious notice. Visual processing and motor control are two well-studied examples of this, with lots of cylinders firing under the hood to perform feats that some of our best engineering efforts still can’t match in many aspects, but appearing to conscious awareness as a seamless presentation of external goings-on.

The reason I’m bringing it up is that I think it would be entirely plausible to have a hive-agent that was capable of intelligence, in the broad sense of behaving like an agent with beliefs, desires, and goals, and yet not exhibiting features of conscious awareness or linguistically-mediated interiority (no “inner monologue”) the way human beings do. This isn’t to say that such an agent would have no self-concept, but it wouldn’t necessarily have the sort of unitary ego-self and corresponding introspective, reflective awareness that we take as essential to intelligence and intelligent behavior. If intelligence can be described in terms of sub-personal cognitive processing, then there’s nothing mandating any sort of conscious reflective powers in such beings.

“Now language. I like Steven Pinker’s definition of it: Language is a finite set of primitives that when combined yield an infinite number of possible statements. [3] By this definition, language is open-ended. It can be used to say anything. Contrast that to, say, referee signals in baseball. They are a communication system but not a language. A referee can precisely say whether a pitch is a ball or strike, but he can’t use the repertoire of signs to talk about taxes, or explain that the pitcher has just become a free agent. Likewise, a honeybee can precisely state where food is but can’t use its waggle dance to discuss the weather with a human. Animals such as honeybees, birds, chimps, dolphins, parrots, and dogs all have communications systems, some of which are very sophisticated, but they are closed-ended; they do not rise to the level of language.”

Following on some thoughts from above, I think that Pinker’s definition here is perhaps too narrow given what you’re looking for. When we say “language is F”, we can mean two things by the subject of that statement: (i) the actual utterances, signs, expressions (or whatever) that are actually used to e.g. make sounds or inscribe on paper and which are used to engage in dialogical, descriptive, or expressive speech acts; or (ii) the cognitive capacity to understand the meaning of words and expressions and thereby engage in the activities that constitute participation in language as (i).

Given the close connection between human intelligence and the capacity for language (ii), I think it’s the broader conception of the cognitive capacity, or set of capacities, that is of interest to you. It is less the rough elements used in a third-party description of speech practices and more the ability of particular agents to demonstrate certain abilities of communication and understanding (part of which is expressing thoughts and understanding other expressed thoughts). I think this is especially important given that life of non-terrestrial origin may not share anything like language, insofar as having discrete words and well-formed propositions that are expressed in spoken or written sentences. In taking that for granted but ignoring the demonstrative or performative characteristics that are essential to understanding speech, we might too quickly overlook signs of intelligent action.

To tie both of these remarks back into your premise, I think what we’d be looking for is intelligent behavior broadly construed: certain properties or actions that reveal a responsiveness to the environment and the deliberate intervention in the environment in a manner that cannot be best explained by brute instinct. Behavior of this sort is not necessarily mediated by overt signs of language as humans have it, but there certainly would be a medium of communication and of description, categorization, and conceptualization. I don’t take it that our brains are the only viable means of enacting such capabilities, even if they’re the only examples we have at the moment. The scenario you outline is at least a plausible one.

In addition to the distributed “hive mind” model, there is the “master brain” model: the Queen of a hive grows a brain large enough for cognition, and has a way of passing commands and receiving information from unintelligent drones.

Nothing to add to the interesting ideas presented here, except that I would like to compliment Sara for having the wisdom and patience to observe and learn in situations where most of us would simply have reached for the bug spray.

Hi Mike,

This is a really excellent essay and you’ve got some great ideas. People’s responses have been brilliant and informative to read too. I don’t have too much to add regarding the feasibility of your idea for insect intelligence, other than nod a lot and say ‘yup’ – when it comes to alien life then I think anything plausible is fair game.

I do have a question for you, however. Obviously, some form of language or complex communication is necessary to build communities that become the basis of a civilisation, that permits the transference of ideas and the development of science and technology. But are we considering science and technology as an inevitable consequence once language reaches a certain degree of sophistication? I ask because I don’t necessarily see science and technology, or even civilisations, as inevitable products of intelligence (partly because I think intelligence is a sliding scale – there are a lot of intelligent species on Earth that are not going to produce rocket ships or radio telescopes any time soon, but dolphins, chimps, gorillas, etc are still intelligent and communicative).

Just as we tend to view our world in an anthropomorph-centric manner (forgive me, english majors), I think we also tend to view it in a terrestrial-centric manner; in this case my meaning is not our kind of planet, but the fact that we are primarily land dwellers.

If life develops first in a wet or moist environment before migrating or being deposited into or onto a relatively dry environment (aquatic first and then land dwelling later), many obstacles lie in the way. At least higher organisms must physically change so as to have new or added methods of motility, metabolizing “breathing” gases, reproduction and a host of other extreme complications to overcome.

If you are going to pursue an “insect civilization” or “insect race intelligence” path, you might consider that the best place for such insects to dwell would be in or under water (or at least some kind of liquid medium). As you are well aware, we have many kinds of such creatures in the waters of Earth (and most of these are mighty tasty too). Such creatures are underwater bugs or are related to them. Lobsters, crayfish, shrimp (and by a stretch, crab) come to mind. Others reading this will probably think of other examples and may rightly fault the mention of crab). The ancient sea scorpions mentioned in a previous post also come to mind. Most of these are capable of swimming and allowing currents to sweep them from location to location and therefore have no need to develop flight or other more advanced motility. Such animals are already more protected from UV flares of red dwarfs than are any land dwelling cousins.

As to the idea of a “larval neural network”; while I don’t disagree with the concept, I think this would limit “thinking” to be a slow process relative to the near-instant interaction of neural connections as they are at present constituted, since “third party” bugs are required to move from larva to larva to facilitate the transfer of information.

Perhaps in an aquatic environment, the transfer of information could be realized by releasing chemicals in general or pheromones in particular into the ambient liquid such that trails are not required, only chemical saturation sequences; this not requiring direction but only proximity. The direction of communication would be controlled perhaps by resting or fixed cell creatures. In the example of hive cells, we have up, down, lateral, diagonal and perhaps depth directions for information to be transferred along.

Hmmm, for some reason I feel like having a peanut butter and honey sandwich.

Good luck!

Funny, if I was going to speculate about intelligent insects, I would base it on a planet with a low gravity, where exoskeletons would be viable at a larger size and hence encourage individual intelligence.

If you are committed to that sort of planet or to a hive mind idea, then the scenario seems believable. Given what we know about alien species (nothing), I have no problem considering it possible. At the end of the day, they are small aliens with exoskeletons, not insects. They might for example, be more similar to mollusks (which actually can high individual intelligence or almost none).

The principle problems for me would be the high gravity environment and adapting their bodies to fit it. Is it better to have short stubby legs? More legs or fewer? This sort of thing is much easier to imagine and poke holes in than the idea of intelligence. Even our own intelligence is mysterious to us in many ways.

Really, what’s going to matter is how well you pull off the consciousness/civilization that you’re talking about. Is it compellingly different from us, and internally consistent based upon the conditions you’ve given it? That’s what would matter to me as a reader.

To everyone who’s responded so far, thank you so much! I’m delighted with your thoughtful responses and excellent ideas, and I’ve been reading (and re-reading) them all slowly and carefully. I plan to write a long comment in two or three days responding, and in some cases asking for clarification and more detail. In the meantime, I hope more readers will weigh in over the holiday weekend. Thank you so much again for taking the time to read, think, and write.

There is an odd inversion of this idea in modern science fiction. T.J. Bass (not a pseudonym!) wrote two novels called Half Past Human and The God Whale. The two comprise actually one novel. For some reason most of humanity ops for as big a population as the Earth can support. Seemingly all of humankind is given over to some kind of ‘machine entity’ (it seems?) which genetically engineers human to be smaller, quite small, with four toes, called Nebbishs. Most of civilization goes underground into a vast Hive of tunnel like cities. There is trillions of Nebbish. There is a kind of social engineering from a hand-that-rocks-the-cradle. The surface is a vast farm, but there are also wild five toed humans who have survived. Bass does not say anything about how it came to be or is administered or really explained. There are adventures, with the surface, but in concept this is kind of a satire on population growth. It is a weird and clever story. I don’t think T J Bass wrote anything else! A very strange set of books.

Recommended.

Looking forward to the book, Michael. It’s a subject I’ve been curious about myself, specially with regards to how difficult it would be to establish comminications with an alien culture.

I think the main problem with your idea of insects (or larva) as the “neurons” of a collective brain is simply one of numbers. There are 100 billion neurons in a human brain, and an average ant colony has only a few thousand individuals. That is a huge gap, and I don’t see how it could possibly be bridged. There are very likely physical limits to the size and density of an ant colony that make it fall short of the size and connectivity of a human brain by many orders of magnitude.

The long-term memory problem is much easier than the sheer numbers problem. It would probably be easiest for the long term memory to be contained in the ants themselves, i.e. each ant has a persistent “list” of other ants that it listens to, each item of that list would correspond to one synapse. The medium of communication could be DNA based pheromones. Each ant would have a unique repertoire of DNA codes that it emits, and another unique repertoire of receptors to sense other ants’ pheromones. The varying repertoires could be generated quite plausibly using the same mechanisms as those used in the adaptive immune system of vertebrates. They could have the requisite plasticity for learning just as the immune system has the plasticity to adapt to unanticipated threats.

This is incorrect. (An old pet peeve of mine.. please indulge me)

The effect of gravity on organisms goes up with the size by the power of 3/2 (mass goes with the 3rd, bone or muscle cross-section compensates with the square). This means that higher gravity can easily be compensated by smaller size. An organism half our size can circulate blood, run, leap or throw at 1.5 g better than we can at 1 g. Also, not being the largest animals on Earth, we are far from being limited by gravity, anyway.

Thus, there is no reason whatsoever to believe that a slightly higher gravity at 1.5 g would be any sort of obstacle for the development of large-brained mammals.

@Eniac

I would look at this as a hierarchical problem. Each insect has 0.1-1 million neurons. Then link these in a colony of perhaps 1 million individuals and you get 100-1000 billion “neurons”.

It would also be interesting to know if insect size is correlated with number of neurons, such that the excess for cognitive, non control functioning increases as well. Is so, those giant insects during the high O2 Carbonferous period could potentially be smarter than their O2 starved cousins (although there is no evidence of that).

As for learning, as long as individuals are “addressable” a network can be created. Imagine a human organization, made up of individuals who are contactable by phone. Each individual is connected to some subset n of the others. If reward/punishment signals based on some environmental input (profits?) are sent down the phone lines, and each individual changes his message (“great, do more”…”awful, do less”) in response to the the messages he receives, the organization should learn just like an ANN. Just as humans in organizations don’t need to know the “big picture”, just their particular function, an insect colony could similarly learn. However, as I have said before, I like the idea of more permanent storage by creating artifacts to store information. One very simple idea strikes me, that would work for a limited information store would be to store information as occupancy of cells in a beehive. Cells could be given signals that allow or dissuade eggs to be placed in the cells, thus creating a readable binary storage device. Crude, low storage capacity, hugely resource intensive, but conceptually possible.

Other binary storage could be dome, e.g. laying down bumps or pits in the walls of the nest. Insects passing these walls could “read” and act on the information, while others could modify it (“write”).

Finally, just as we store information in DNA, it might be possible for some lifeforms to read/write DNA outside their cells, offering a high density long term storage mechanism. One way this might work is to store special “genes” in a cell that when read, sends out serial signals (electrical/chemical) that could be perceived by the organism. Our terrestrial DNA/RNA read rates are far to fast for this to work, but perhaps it could be done by other methods, perhaps perceiving and interpreting unique sequences of DNA/RNA/protein directly and holistically with chemical sensors.

Got around to reading the rest of your exposition. As I stated in my first comment, an “alien” civilization is for me of a nature that is unlike anything that has arisen here. Simply projecting our own methods and capabilities on another species be it land, air or water based is not enough to satisfy me. Haven’t read Schätzing’s Der Schwarm, Hofstadter’s Ant Fugue or anything along those lines, so I can’t say if I’m repeating the ideas of anyone else. Just a couple more points, my vaguely conceived pheromone-ish world was only one idea for a control mechanism. Another my be parasite based, for example. It’s been done to death in tons of bad SF but, there is still a lot of halfways conceivable potential. One variant would be for the controlling parasite to be productively distributed to a variety of key “subordinate” species. Each parasite tailored(somehow) to achieve a particular sub-objective in the overarching bioimperative of a dominant species depending on the paricular benefits of the subject. A hive queen could perhaps be infected by such means thereby mobilising it’s colony in a slightly altered manner one suiting the infector species. Defence and offense would be in constant struggle of course. Viruses are perhaps also interesting given their propensity to usurp the genetic processes in the host thus opening another realm of potential subjugation, maybe through something like manipulation of the endocrinal system. Most interestingly, I think without killing the host. Enormous networks of essentially slave labour are the reward. To make from this a mindless civilisation, even more a mindless technological(within limits) civilization, one needs a very unusual base motivation. Not reproductive success. Sex can’t be that complicated. Territorial security is more conceivable. Environmental factors and threats need to be also more complex that we have here on Earth. That may sound ridiculous. But, I think its not so improbable. A story along these lines I think must be written top down. A look at a functioning civilisation of this order will reveal all that is needed to create the world and its developmental history.

“I’m asking you to put pressure on these ideas.”

Please remember that I’m trying to create a non geocentric civilizational construct. Something new. Not derived from terrian examples. In this sense my take is that “long term memory” (not individual rather societal) could be achieved through archival processes. My previously painted world doesn’t need this. However, the capability of generational transfer of advanced structural knowledge is undoubtedly beneficial for a number of reasons. This transfer is, however much more difficult to conceive when working on the premise that higher cognition and semantics don’t exist. The archival process might be triggered only upon achievement of particular classes of biocivilatorial goals. Medium and method and mechanism of subsequent generational exploitation I haven’t thought out yet. It’s 4 in the morning and I’m getting a little tired. More later.

@TLDR and @AlexTolly came close to the fundamental problem of this discussion. @TLDR is absolutely correct in the claim that we are way too far anthropocentric in this discussion. By the very definition of ET, whatever they are they will be alien to us in every aspect. That must be understood to proceed. In other words, what does author mean by “insects”? Alien life WILL be alien and alien-insect has no meaning. Life somewhere else will emerge under its own conditions and evolve under its own conditions. At best the question is “can alien intelligent life evolve in the form of collective intelligence instead of individual one as in our case?”. Yes it can, nothing prevents that if planetary and evolutionary conditions give it advantage and chance. Earth evolutionary track is just one in billions possible ones, even on a very similar planet it would be trivial for life to take completely different paths.

Now to communicating with it, @AlexTolly quote “Some ETIs, and certainly many life forms, will be too alien for us to comprehend. As you suggest, we cannot communicate with almost all terrestrial life, and even with our closest relative, the Bonobo, we can barely hold much of a conversation. To communicate with ETs, they will need to be at some sort of equivalent level of intellectual sophistication as us.” – It is certainty that alien life will be completely alien to us.Communication problem is not the one of “equivalent sophistication” but at the very conceptual level. Example: the very concept of “communication” may mean something completely different to equivalently sophisticated alien ET. Author also makes this mistake. “Language” may be based on whatever foundation (ex. imagine that dolphins have evolved language-equivalent by communicating 3D sonar images which we than try to map to our verbal constructions… even at that simple level sophistication would not be the problem but anthropocentrism, we hear clicks – we think words, they see complex images). Best Sci-Fi case that quite integrates all of these problems is Solaris: singular planetary organism (obviously not any Earth-like class of life, insect or mammal or…), sophisticated for communication with us but what it thinks of “communication” is so far from us that when it reaches us (and it reaches us and we get it!) it drives us mad…

Finally, even bigger problem author skips over is in alien societal and moral constructs. They need not be anything like ours. Hence, the most important evolutionary barrier is “death by contact” and the only solution for that is avoiding contact if we do not know that we are the more powerful followed by avoiding contact with morally incompatible ETs (ex. 4th of July aliens or Martians from Mars Attacks Sci-Fi types).

@Alex

Yes paper could used as well as using the fibres with knots made in them, much like what the Inca’s did to record information, Quipus.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quipu

Ants been much smaller could store a very large amount of information using these knots, they could also make use of their digestive and defensive chemicals to etch information into stone as well. As for the pheromones they could be mixed with other chemicals or absorbent materials to make them last longer.

Below is a website discussing the development of the Human brain and the so-called supermind.

http://www.colorado.edu/news/releases/2011/04/20/evolution-human-super-brain-tied-development-bipedalism-tool-making

The evolution of humans too the intelligent, tool using, language speaking creatures we are today is complex, requiring the development of large brains, bipedalism, opposable thumbs, and binocular vision. Our abilities to refine tools led to the development of language. Chimps or other related species can be seen using a simple tool such as a rock or bone to break something. They do not make something like a stone axe or knife. That is unique to humans. The ability to shape these tools is the forerunner of language. We were able to visualize a shape and then make it. This produced shape is different than objects that occur in the natural world. Binocular vision and opposable thumbs paid a huge role in more sophisticated tool development. Once you can visualize tools you can start visualizing other concepts. Then comes language. (Don’t forget the impact of bipedalism that freed our hands to carry tools and weapons, though there is a debate which came first, tool making or bipedalism. I suspect they sort of supported each other,)

The point is I don’t see a hive mind going through this kind of evolution to tool making and civilization. If an insect civilization were to evolve, I think it would be more like Bob Heinlein’s in Starship troopers with brain caste insects. My argument against that form of development is lack of diversity. In humans, creativity is not limited to scientific geniuses. Think of the master toolmaker who develops a way to make a new tool, changing the process on a lathe to accommodate a design. That’s more than the instinctual construction of a honeycomb by a honeybee. It’s a creative process.

So to me, the hive mind and brain caste insects are too limited in diversity to form a technical civilization as we know it I could imagine a honey bee on a low gee world growing big enough to develop into a bipedal insect with binocular vison, opposable thumb, and a brain size to body mass that is 7 or 8 times greater than it is for other species. But this is not what you’re aiming for. Am I anthropocentrizing? Maybe so but that’s where the trail of our evolution leads us. Just my thoughts,

chael Chorost, excellent essay, followed by (as always on this site) an excellent discussion.

I agree with NS. Excellent observational work, Sara.

I also agree with Eniac, that there is no reason to expect that 1.5 gravities would be a limiting factor on the evolution of larger-than-insect organisms.

But I most agree with Keith Cooper:

“But are we considering science and technology as an inevitable consequence once language reaches a certain degree of sophistication? I ask because I don’t necessarily see science and technology, or even civilisations, as inevitable products of intelligence (partly because I think intelligence is a sliding scale – there are a lot of intelligent species on Earth that are not going to produce rocket ships or radio telescopes any time soon, but dolphins, chimps, gorillas, etc are still intelligent and communicative).”

Whenever I come to centauri-dreams (and I do often read and seldom post) I always have either lurking in the back of my mind or right up there in the front, continuing wonder with regards to the Fermi Pardox.

As has been discussed on this site many times, the self-replicating drones should be here by now. Where are they? I know, there are a million different answers to that question, but to me the one that makes the most sense is alluded to by Keith.

I suspect that in our universe, life is everywhere (maybe on a billion planets per galaxy), that intelligence is commong (maybe on a million planets per galaxy) but that technology is rare.

I suspect (and I know, my suspicions plus $2 will get me a Tall Pike at Starbucks) that technological civilizations are on the order of one-per-galaxy, or less.

So where are they? They are we, at least in this galaxy.

So Michael Chorost, I believe your excellent hypothesis is very logical and for what it’s worth “possible”, but that it would fit right in with what Keith is suggesting (or at least the way I am taking it), that an insect hive intelligence as you describe is possible but that the No Technology probability would be strictly observed.

Sorry, Keith, if I am misrepresenting your idea in any way.

Fascinating piece.

But not convinced.

I don’t believe that an insectile-like species cannot form a civilization based on your parameters for civilization. That being said, I am not willing to allow all future technical advancements and ‘individual’ unit upgrades to be excluded.

If we stretch your definitions as I have interpreted them:

The individual unit can function, survive, reproduce, evolve, and communicate/affect completely on its own – as would loosely follow the fundamental definition of life, though it does not create a sustainable and self-reinforcing cultural identity.

Also, I assume the unit can store its survival experiences and understand similar experiences and adapt to experiences different from its own but outside of its existing context if those new experiences and context suddenly made themselves present (i.e. a forest unit could become a desert unit on its own after a period of adaptation). We’re talking about an individual that aspires to affect its surroundings and has some adaptability to thrive – not just a reactionary-only bacteria or virus or an analogy to an appendage.

The key here is that an instantaneous transmitting device that would be implanted/attached to communicate a flow of ‘experiences’ to all others. We assume that the individual has the potential to overlap/integrate the experiences of others and ‘upgrade’ itself temporarily to the potential of the communication/language that would result from the constant exposure to ‘other’ experiences. From the simultaneous upgrade, the temporary exposure to all other experiences would be the same as memory as they would only be accessing that experience that would be useful at that time. As the implanted/attached connection and ‘cultural search engine’ unit was removed, we could then assume that the unit would diminish to its original survive only mode. The question is whether the temporary ‘ansible’/ search engine was a actually a cognitive upgrade or only a temporary tool, not fundamental to the individual, but fundamental to the cultural ‘bandwidth’ required. I would say that it was only a tool and that culture within the individual is fleeting and arbitrary but that there has to be a repository of ‘social’ potential, perhaps a microcosm of the collective, within each individual that divides them from ‘barely’ life and a functioning unit – which is what I assume we are talking about – a product of evolution, for which I believe, a fundamental part has to be a ‘civilization’ gene. You cannot have the ‘evolvable’ individual without the potential of the collective within it – though it may follow a path away from the collective, as diminished as that may be. I suppose the other issue is that collective memory need only be stored temporarily and could simply be passed around infinitely provided there were enough individuals to store a tiny fragment of a moderately related experience, so that in effect, all knowledge within the civilization was circulating throughout the collective infinitely, if only as a flash in the pan as one individual accessed it to compare it to their current experiences only. Similar to all human knowledge being stored in computers that were on and connected with people that were alive and communicating. You don’t need long-term memory as much as a transcendental circulation and retrieval system within a constantly changing hive – perhaps a like an error checking system where the integrity (knowledge history) of the hive is always checked continually and updated and re-distributed — a two-way search engine. We may even find this to be an upgrade on our current definition of civilization (or the possibly forthcoming civilization of the cloud’.

Are technological cultures rare, but ETIs common? I don’t think this is likely for these reasons.

1. Earth species that can manipulate their environment transcend phyla. Therefore while we humans have both brains and dextrous hands, other phyla also have brains and an ability to manipulate objects, or little brain and manipulative capabilities. The whale species are perhaps the best counter example – large brains but with no manipulative appendages other than their mouths. But Molluscs (e.g. squid and octopus), Arthropods (insects, crustacea) are quite adept and manipulation on their scales.

2. We see examples of tool use in manipulative species. Whilst we used to have the conceit that only humans are tool builders, it is now clear than a number of species have been observed to use tools, suggesting to me that this is a common trait of any animal that can manipulate its environment.

3. While modern civilization is science based and has emerged in the last 250 years, pre-scientific cultures have shown a remarkable capability to build and extend their tool use by trial and error.

It may just be that it was the “fluke” of Western Enlightenment science that proved the impetus to bootstrap our civilization to where we are today. In which case, if there are intelligent species in the galaxy, then perhaps most are stuck at a pre-scientific stage, unable to advance sufficiently to be able to signal their presence except by their impact on their planets. However, they could potentially have a rich culture.

Regarding communication. I’m sure that alien species might well be very difficult to understand conceptually. But here I partially agree with McCarthy’s thesis that intelligence converges. Tools will obey laws of physics, and therefore I think that how they work represents a common mapping between species. A hammer is a hammer whether on Earth or on Tau Ceti 5. What we build with that hammer may be difficult to comprehend, but the use of a hammer is going to be a common referent to start to build more meaningful communication. Clearly I am arguing in favor of the “math is common” idea, but extending it to physical tools, rather than symbol manipulation.

The problem is more likely to be that when we meet ETI, they might view our tool use as primitive as Bonobo’s using sticks. If so, might they be “post-tool users” – so sophisticated that they no longer use what we would understand as tools? In which case we lose any possible tool use referents.

I enjoyed Michael Chorost’s speculation on the possibility of language using, technologically sophisticated aliens resembling terrestrial insects. However, I think there are five arguments against their existence.

First is time. Insects have existed, in recognizable form, since the Ordovician, about 480 million years ago. They outlasted the dinosaurs. Yet, in all of that time, insects never developed intelligence. Humans only took 130 million years to arise after the origin of mammals. A difference factor of better than three suggests something fundamental blocks the insect road to intelligence.

Second is numbers. Insects have always been numerous, well-adopted to a wide range of environments. Humans, on the other hand, nearly went extinct some 70,000 years ago according to the Toba theory. The numbers of humans may have dropped as low as 10,000. These individuals would have been the fittest survivors, perhaps the most intelligent. Inbreeding may have amplified those characteristics. Insects, to our knowledge, have not been subject to those pressures.

Third is offspring. Insects produce large numbers of genetically identical individuals. Genetic abnormalities are destroyed by the colonies. Humans also destroy their undesirables but human emotions sometimes spares the knife.

Fourth is emotion. Many researchers in the field of intelligence believe human emotion is essential to the development of intelligence. Sadness, happiness, remorse and exultation combine with desires to produce minds capable of imagination, speculation, hypothesizing and non-obvious combinations of information. Insects, like computers, do not have the mechanisms for emotion, although it could be speculated alien insects might not suffer from that deficiency.