As I sat down to write yesterday morning, I realized there was a natural segue between the 1977 ‘Wow!’ signal, and the idea that it had been caused by two comets, and KIC 8462852, the enigmatic star that has produced such an interesting series of light curves. What I had planned to start with today was: “Are comets becoming the explanation du jour for SETI?” But Centauri Dreams reader H. Floyd beat me to the punch, commenting yesterday: “Comets are quickly earning the David Drumlin Award for biggest SETI buzzkill.”

As played by Tom Skeritt, David Drumlin is Ellie Arroway’s nemesis in the film Contact, willing to knock down the very notion of SETI and then, in a startling bit of reverse engineering, turning into its champion as he claims credit for a SETI detection. And of course you remember controversial KIC 8462852 as the subject of numerous media stories first playing up the idea of alien mega-engineering, and then as quickly declaring the problem solved by a disrupted family of comets that moved between us and the star in their orbit.

But KIC 8462852 doesn’t yield to instant analysis, and it’s good to see a more measured piece now appearing on New York University’s ScienceLine site. The title, Tabby’s Mystery, is a nod to Tabetha Boyajian, a postdoc at Yale University who noticed that the dips in light in Kepler data from the star were unusual. We have the Planet Hunters group to thank for putting Boyajian on the case, and a productive one it has turned out to be. As writer Sandy Ong notes, KIC 8462852 produced non-periodic dips in the star’s light that in one case reached 15 percent, and in another 22 percent.

Image: Yale’s Tabetha Boyajian, whose work examines possible causes for the unusual light curves detected at KIC 8462852.

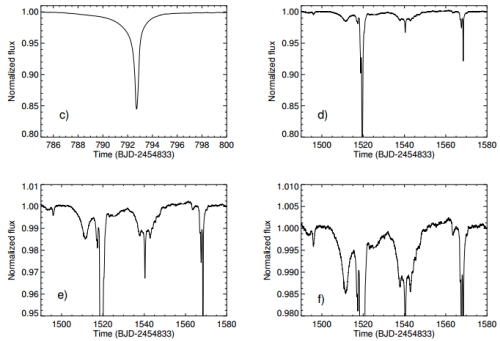

‘Tabby’s star’ is one name KIC 8462852 has acquired, the other being the ‘WTF star’, doubtless standing for ‘where’s the flux,’ given the erratic changes to the light from the object. I’ve written a number of articles on this F3-class star and its light curves, noting not only the size of the two largest dips but also the fact that the dips, unlike those of a transiting planet, are not at all symmetric. Ong quotes Boyajian as saying: “The first one is a single dip that shows a very gradual decrease in brightness, then a sharp increase… The second dip has more structure to it with lots of ups and downs.” For more, see KIC 8462852: Cometary Origin of an Unusual Light Curve? and search the archives here, where five or six other articles on the matter are available.

Comets come into the mix because in Boyajian’s paper on KIC 8462852, they are named as a possibility. To refresh all our memories, let’s go back to the paper:

…we could be seeing material close to the pericenter of a highly eccentric orbit, reminiscent of comets seen in the inner Solar System at pericenter. We therefore envision a scenario in which the dimming events are caused by the passage of a series of chunks of a broken-up comet. These would have to have since spread around the orbit, and may be continuing to fragment to cause the erratic nature of the observed dips.

Comets moving close to the parent star would be given to thermal stresses, and could also be disrupted by close encounters with planets in the inner system. For that matter, tidal disruption by the star itself is a possibility. Boyajian and co-authors point out that a comet like Halley would break apart because of tidal forces if approaching as close as 0.02 to 0.05 AU.

We have WISE data from 2010 showing us that KIC 8462852 lacks the infrared signature a debris disk should produce. But the unusual light curves from Kepler began in the spring of 2011, so for a brief window between the two, there was the possibility of a planetary catastrophe, perhaps a collision between a planet and an asteroid, that would explain what Kepler saw. But Spitzer Space Telescope observations in 2015, analyzed by Massimo Marengo (Iowa State) and colleagues, found no trace of infrared excess at the later date, which seems to rule out a collision between large bodies and leaves the hypothesis of a family of comets still intact. See No Catastrophic Collision at KIC 8462852 for a discussion of Marengo’s work.

Image: Montage of flux time series for KIC 8462852 showing different portions of the 4-year Kepler observations with different vertical scalings. Panel ‘(c)’ is a blowup of the dip near day 793, (D800). The remaining three panels, ‘(d)’, ‘(e)’, and ‘(f)’, explore the dips which occur during the 90-day interval from day 1490 to day 1580 (D1500). Credit: Boyajian et al., 2015.

Perhaps we’re seeing a natural phenomenon we can’t yet identify. Ong cites Eric Korpela (UC-Berkeley) on the matter:

“I like the comet explanation although ‘comet’ might not be the right word,” says Eric Korpela, another astronomer from the Berkeley SETI Research Center. That’s because the core of such an object would have to be as large as Pluto in order to generate this kind of light, he explains.

Korpela and other astronomers believe the dimming may be due to some kind of natural phenomenon we haven’t yet seen anywhere in the universe. “We just haven’t looked at enough stars to know what’s out there,” he says.

What we saw yesterday with relation to the ‘Wow!’ signal is that we will soon have two chances to monitor the comets involved in Antonio Paris’ hypothesis for generating the signal. In like manner, we’ll have further observations of KIC 8462852. Ong notes that the Green Bank instrument in West Virginia is involved, as are the MINERVA array in Arizona, the MEarth project (Arizona and Chile), the LOFAR telescope in the Netherlands, and amateur observations from the American Association of Variable Star Observers, who will bring their own instruments to bear.

Oh to have a healthy Kepler in its original configuration returning new data on KIC 8462852! But despite the outstanding work being performed by the K2 ‘Second Light’ mission, the instrument is now working on different targets, and our ground-based telescopes have to do the job. What we need to know is if and when ‘Tabby’s star’ starts producing further light curves, and just what they look like. SETI observations have already been attempted using the Allen Telescope Array (see SETI: No Signal Detected from KIC 8462852) looking for interesting microwave emissions. None were found. Expect this enigmatic star to remain in the news for some time to come.

The Boyajian paper is Boyajian et al., “Planet Hunters X. KIC 8462852 – Where’s the Flux?” submitted to Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (preprint). The Marengo paper is Marengo et al., “KIC 8462852 – The Infrared Flux,” Astrophysical Journal Letters, Vol. 814, No. 1 (abstract / preprint). Jason Wright and colleagues discuss KIC 8462852 in the context of SETI signatures in Wright et al., “The ? Search for Extraterrestrial Civilizations with Large Energy Supplies. IV. The Signatures and Information Content of Transiting Megastructures,” submitted to The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

The anomalies observed are periodic and they exactly match the orbit of the Kepler space telescope around the Sun. It is obvious that it is an artefact due to something about the telescope and that no information is given about that distant star. Even the strange new astrophysical hypothesis about a “comet cloud” doesn’t work, because even comets should be periodical and they aren’t during the chaotic third anomaly period. And for another reasons such as no reflection when that cloud is beyond the star, no IR radiation from their dust, the size scale of things, it is just not a valid hypothesis, has this really been peer reviewed and published?

My respect of the astronomical community is seriously degrading because of this sick hype, without anyone professional in the business stepping up and publicly explaining how it is flawed. “Tabby’s star” might become a very bad brand name for similarly hyped mistakes.

The observations seem to be about 726 days apart.

When is the next darkening due?

Local Fluff said on January 13, 2016 at 14:18:

“The anomalies observed are periodic and they exactly match the orbit of the Kepler space telescope around the Sun. It is obvious that it is an artefact due to something about the telescope and that no information is given about that distant star.”

I am not discounting your observation but I am surprised that professional astronomers would not take this into account. And yes I know everyone makes mistakes.

And there is data about the star itself:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/KIC_8462852

Were the astronomers in need of more resources/money to better study this star and declaring that there might be a Dyson Swarm about it was one way to get attention? I am not saying they had an ulterior motive, just guessing in the event such a thing were possible.

WTF = Where’s The Flux = Hilarious! Paul, that was great. I laughed out loud for a couple of minutes. :)

Instrument error, telescope artifacts – those are factors examined as soon as possible after a paper is submitted for publication, if not before submission. The Sept. 2011 faster-than-light neutrinos at CERN come to mind as a well-known example. The experimenters had checked the instruments themselves before the announcement and didn’t find any error. After the announcement researchers around the globe duplicated the CERN experiment, attempting to duplicate the result.

CERN’s head of research was publicly skeptical, so much that he gave the hilarious statement that the neutrinos couldn’t have traveled FTL because because the neutrino receiver was in Italy, and “nothing in Italy arrives ahead of time.”

None of the duplicate experiments obtained the FTL result, which rightly raised suspicion. By Feb. 2012, the CERN team’s detailed follow-up investigation of the equipment determined that equipment error was indeed the cause of the FTL speed measurement. A loose cable in the GPS which was used in timing the neutrinos created the erroneous FTL result.

If instrumental artifact or human error is the cause of the KIC 8462852 light curve measurements, the error will be discovered. Due to the import of these particular light curves, any error or artifact will likely be discovered sooner rather than later.

Is the evidence that the KIC 8462852 light curves are caused by an extraordinarily large family of comets stronger than the evidence that said light curves are caused by a planet 20 times larger than Jupiter?

Is the evidence for either the mega-family of comets or the mega-Jupiter stronger than the evidence for transiting mega-structures built by an alien intelligence?

Erik Landahl writes:

Wish I could claim it, but check the title of the Boyajian paper ;-)

“The observations seem to be about 726 days apart.

When is the next darkening due?”

I think the next one would have been in 2015, but Kepler wasn’t looking at it then. Either we just missed it, or it’s about to happen. I can only assume that somebody somewhere is monitoring it. Has ALMA looked at it?

Has anyone produced a model showing what shape object or objects would create the light curves? I can’t see it being comets. They aren’t either large enough or opaque enough to do it. Perhaps a planet with a large ring system might work, but the light curve should be the same each time, and it’s not.

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1601.03256.pdf

This paper describes a secular dimming over a century which rules out comets and (if I understand it) virtually rules out dust as the cause of the dips.

But a slow dimming almost looks like many small objects being constructed, like a Dyson Sphere in mid construction.

Seriously, a Dyson Sphere still seems far-fetched to me, but the paper makes it obvious that WTF-001 is well deserving of its nickname!

Well now today this new paper came out…

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1601.03256v1.pdf

“The century-long dimming and the day-long dips are both just extreme ends of a spectrum of timescales for unique dimming events, so by Ockham’s Razor, all this is produced by one physical mechanism. This one mechanism does not appear as any isolated catastrophic event in the last century, but rather must be some ongoing process with con- tinuous effects. Within the context of dust-occultation models, the century-long dimming trend requires 104 to 107 times as much dust as for the one deepest Ke- pler dip. Within the context of the comet-family idea, the century-long dimming trend requires an estimated 648,000 giant comets (each with 200 km diameter) all orchestrated to pass in front of the star within the last century.”

Kepler error? Highly doubt it.

Local Fluff said on January 13, 2016 at 14:18

The anomalies observed are periodic and they exactly match the orbit of the Kepler space telescope around the Sun.

Kepler orbits the sun in 372.53 days (Wikipedia) not 726/727 days.

Instrument error has been investigated and has been discussed extensively here at CD and in papers.

There appears to be no instrument cause for these light curves and therefore should be considered an artefact of something coming between Kepler and KIC 8462852. Would be interested to know if anyone has additional information not in the public domain that suggests otherwise.

Erik L: Re: Dimming caused by a planet 20 times larger than Jupiter. Someone, correct me if I’m wrong, but as I understand it a hypothetical exoplanet CAN of course have a mass 20x larger than Jupiter, but it’s diameter will stay about the same as our Jupiter: as you add more mass it just gets denser. It strains credibility to think that even some massively giant swarm of comets will block up to 22% of Tabbys star’s light. Some of the dimming events last up to 15 days long, which implies a wide, slow orbit. And only this star, out of all the KOI (5000? candidates), we catch at just a the right time to see this swarm, with perfect timing just AFTER WISE looked at it….. The least convoluted explanation maybe ETI. Can we all agree…. 5 more years of data are needed with every scope we can muster!

“KIC 8462852 Faded at an Average Rate of 0.165+-0.013 Magnitudes Per Century From 1890 To 1989”

http://arxiv.org/abs/1601.03256

I will let others discuss implications of this significant observation…Either a very weird star or….

More from the paper above:

“The century-long dimming and the day-long dips are both just extreme ends of a spectrum of timescales for unique dimming events, so by Ockham’s Razor, all this is produced by one physical mechanism. This one mechanism does not appear as any isolated catastrophic event in the last century, but rather must be some ongoing process with continuous effects. Within the context of dust-occultation models, the century-long dimming trend requires 10^4 to 10^7 times as much dust as for the one deepest Kepler dip. Within the context of the comet-family idea, the century-long dimming trend requires an estimated 648,000 giant comets (each with 200 km diameter) all orchestrated to pass in front of the star within the last century. “

@Local Fluff (love your choice of name, by the way)

There have been two big dips 750 days apart, and lots of smaller dips. Kepler’s orbital period is 372 days, so okay let’s be charitable and say for roughly every two Kepler orbits it sees a big dip, up to 22 percent. But there have been many more smaller events between those two big ones, with periods ranging from 5 to 80 days – if you look at the light curve it is covered with dips, which is where the inference of a swarm has come (and why it can’t be one solid body like a planet). In their paper Boyajian et al also considered instrument and processing effects and ruled them all out (including checking neighbouring stars to make sure they weren’t showing the same effect at the same time). If it is an artefact to do with Kepler’s orbit, then it chooses to manifest itself in just one faint star.

Match the dips with the quarters of the telescopes orientation. Dates here:

http://keplerscience.arc.nasa.gov/ArchiveSchedule.shtml

Only the final quarter presents repeated anomalies, but all within that same quarter. A failure of a small part of the CCD together with orientation seems a very much plausible explanation than anything astrophysicists have come up with. The paper does not mention the exact correlation between the anomalies and the orientation of the telescope. It seems not to have been taken care of.

BREAKING NEWS! The DIMMING of KIC8462852 has been going on since AT LEAST 1890!! Somebody took up my plea(from an earlier comment) to check EVERY ARCHIVAL PLATE available for the last 100 years. HERE ARE THE RESULTS: KIC8462852 Faded at an AVERAGE RATE of 0.165 +or- Magnatudes Per Century from 1890 to 1989, by Bradley E Schaefer, available NOW on the Exoplanet.eu website(and I assume, astro-Ph as well)! The last sentence from the ABSTRACT is as follows:…the century long dimming trend requires 10 to the fourth power to 10 to the seventh power times as much dust as for the one deepest Kepler dip. Within the contest of the comet family idea, the century-long dimming trend requres an estimated 648,ooo giant comets(each with a 200KM diameter) all orchestrated to pass in front of the star within the last century.” I haven’t read the PDF yet, because I couldn’t wait to post this comment after reading the abstract, but my IMMEDIATE(subject to REVISION AFTER I read the PDF) take on this is that the author almost summarily rejects the comet hypothesis in favor of some, as yet, UNKOWN NATURAL PHENOMENA NEVER BEFORE SEEN OR EVEN CONCIEVED! If 648,00 centaur-sized comets have to transit AFTER FRAGMENTATION every century, How many NON-TRANSITING comets of the same size must ALSO have fragmented in the SAME time-frame, and what percentage of comets this size must have been flung into orbits allowing the fragmentation. This percentage would allow you to derive the total population of 200KM comets in the system. WHEN THIS COMPUTATION IS DONE, I postulate that the number will be WAY TOO HIGH for an Oort Cloud and Kuyper Belt of a star of KIC8462852’s mass. Jason Wright, PLEASE RSVP ASAP after you have read the PDF(if you have not done so ALREADY)>

I do not buy that this is a giant swarm of comets. We would see far more systems with a similar situation if so. Pardon me if this is my gut reaction based on a lifetime of studying such subjects.

I am not saying it is artificial, either, but in this particular case it is the experts bending themselves into pretzels trying to come up with some kind of natural explanation. All it really shows is how much we do not know and how provincial humanity still is.

I also doubt the Wow! Signal was due to comets, but I also don’t think it was from aliens, either.

Things are getting very messy for KIC 8462852. Looks like we are going to be studying this star intensely for a long time to work out exactly what is going on.

A century long dimming event appears to have occurred.

http://arxiv.org/abs/1601.03256

Wow, this star is getting more and more strange!

KIC 8462852 Faded at an Average Rate of 0.165+-0.013 Magnitudes Per Century From 1890 To 1989

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1601.03256v1.pdf

New paper on KIC 8462852 on arXiv.org

http://arxiv.org/abs/1601.03256

KIC 8462852 Faded at an Average Rate of 0.165+-0.013 Magnitudes Per Century From 1890 To 1989

Bradley E. Schaefer

Abstract:

“The star KIC 8462852 is a completely-ordinary F3 main sequence star, except that the light curve from the Kepler spacecraft shows episodes of unique and inexplicable day-long dips with up to 20% dimming. Here, I provide a light curve of 1232 Johnson B-band magnitudes from 1890 to 1989 taken from archival photographic plates at Harvard. KIC 8462852 displays a highly significant and highly confident secular dimming at an average rate of 0.165+-0.013 magnitudes per century. From the early 1890s to the late 1980s, KIC 8462852 has faded by 0.193+-0.030 mag. This century-long dimming is completely unprecedented for any F-type main sequence star. So the Harvard light curve provides the first confirmation (past the several dips seen in the Kepler light curve alone) that KIC 8462852 has anything unusual going on. The century-long dimming and the day-long dips are both just extreme ends of a spectrum of timescales for unique dimming events, so by Ockham’s Razor, all this is produced by one physical mechanism. This one mechanism does not appear as any isolated catastrophic event in the last century, but rather must be some ongoing process with continuous effects. Within the context of dust-occultation models, the century-long dimming trend requires 10^4 to 10^7 times as much dust as for the one deepest Kepler dip. Within the context of the comet-family idea, the century-long dimming trend requires an estimated 648,000 giant comets (each with 200 km diameter) all orchestrated to pass in front of the star within the last century. “

The plot thickens.

This is a wonderful mystery to have ticking away on the back burner and I wonder what we’ll’ve found out during the next five years of study.

If the curves can be explained by a large KBO-like object breaking up into a cluster of objects/debris after periastron and crossing our line of sight as the debris heads outwards again, I wonder what the orbital period would be. Hopefully not as long as, say, Comet Halley’s seventy-six years… or Hale-Bopps few thousand!

Erik Landahl: As others have said you can’t have a planet 20 times the diameter of Jupiter. Such an object would be a star and would be detected as such.

You could have an object 20 times the mass of Jupiter, but it wouldn’t have 20 times the diameter. It would be hardly any bigger than Jupiter in size.

In response to Local Fluff: Kepler is on a 371 day orbit around the sun. This orbit does not “exactly match” the irregular dimming events observed. Not sure who told you that.

BTW everyone, SETI did detect radio flux from KIC 8462852. The strongest was roughly 97% of their artificially high threshold for “detection”. They just want more and better data before calling it, I suspect. Read the abstract; http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1511/1511.01606.pdf

Yes it does!

At least as far as i can line up the “quarters” with the dips in the graph given in the paper. Given that it was in the 1st quarter during the startup weeks when the first dip was observed. Correct me if it’s wrong.

http://keplerscience.arc.nasa.gov/ArchiveSchedule.shtml

Anthony Borelli said on January 14, 2016 at 14:52:

“BTW everyone, SETI did detect radio flux from KIC 8462852. The strongest was roughly 97% of their artificially high threshold for “detection”. They just want more and better data before calling it, I suspect. Read the abstract; http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1511/1511.01606.pdf

Say WHAT?

“Where’s The Flux?” reminds me of Dewdney’s book critiquing cold fusion “Yes, We Have No Neutrons”.

Anthony Borelli: “BTW everyone, SETI did detect radio flux from KIC 8462852. The strongest was roughly 97% of their artificially high threshold for “detection”. They just want more and better data before calling it, I suspect. Read the abstract; http://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1511/1511.01606.pdf”

I read the paper. Are you sure you did? Your claim seems entirely unsupported.

Ron S: I agree.

Anthony Borelli: CAVAET! 97% is ONLY just above 2 sigma! 3 sigma is 99.7%, which is what Kepler uses to confirm transiting planets. Normally, 4 sigma is required for any kind if NEW discovery(like the FIRST exoplanets). CERN used 5 sigma for the Higgs discovery, AND; the Sagan Rule requires a whopping 6 sigma! There are not ANYWHERE NEAR THE REQUIRED THRESHOLD!

Conclusions

We have made a radio reconnaissance of the star KIC 8462852 whose unusual light

curves might possibly be due to planet-scale technology of an extraterrestrial civilization.

The observations presented here indicate no evidence for persistent technology-related

signals in the microwave frequency range 1 – 10 GHz with threshold sensitivities of 180

– 300 Jy in a 1 Hz channel for signals with 0.01 – 100 Hz bandwidth, and 100 Jy in a 100

kHz channel from 0.1 – 100 MHz.

Either you didn’t read the conclusion, or you’re trolling. I’ll assume on good faith that it was a mistake.

@Larry January 13, 2016 at 21:32

‘Perhaps a planet with a large ring system might work, but the light curve should be the same each time, and it’s not.’

If the planet had moons and a ring system it would be sufficient to cause all of the dimming if the planets ring system was perpendicular to us. The ring system can become distorted easily enough by the light and solar pressure from the star, magnetic smearing as the star is a rapid rotator and gravitational interactions with moons, planet and the star on the ring system. The reason why the timing may be off could be due to the Kozai effect.

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=34791

My money is on a planet with a moon undergoing extreme heating through thermal closeness to the star, tidal distortion or both and evaporating, mostly likely the moon.

@Michael January 17, 2016 at 8:24

I suppose that’s a possibility for the dips, but not for the century-long decline in brightness of some 20%. What I think will need to be done now is to go into the archive of those old photographic plates and look for other cases of stars that have long term declines like this one. It could be that we have stumbled upon a new type of variable star, or an aspect of stellar behavior we weren’t aware of before.

What’s most interesting is that we don’t understand it. I’m 75% in the alien megastructure camp myself, and if that is the case, “they” are utilizing technologies that aren’t showing the infrared signatures we would expect, so there is new science and/or technology to be discovered. If it turn out to be natural, it means we may have to revise our stellar theories to account for this behavior. Either way, it’s a win-win situation for science.

@Larry January 17, 2016 at 12:30

‘I suppose that’s a possibility for the dips, but not for the century-long decline in brightness of some 20%. What I think will need to be done now is to go into the archive of those old photographic plates and look for other cases of stars that have long term declines like this one. It could be that we have stumbled upon a new type of variable star, or an aspect of stellar behavior we weren’t aware of before.’

Hopeful the plates have not degraded over time, if we find a lot more with declines in magnitude then the most likely explanation would be plate degradation and nothing to do with the stars.

“Hopeful the plates have not degraded over time, if we find a lot more with declines in magnitude then the most likely explanation would be plate degradation and nothing to do with the stars.”

On each plate, the star’s brightness was checked against two other stars of the same spectral type. Those “check stars” showed no decline, while the KIC star did.

@Michael

I would assume that the stars do not dim over time and therefore use them to normalize the data from different plates. If the target star is dimming, it will be doing so relative to other stars, especially those nearby.

If it turned out that a group of stars near each other were dimming, but other stars were not, this might imply something in the interstellar medium causing the dimming. I don’t think the state of the plates is much concern, and in any case they are likely to have different exposures and their absolute intensities are not relevant to the study.

Larry: Someone DID envision this technology. Arthur C Clarke, in his Space Oddessy series. A “Black Monolith” is a stargate to transport objects from one part of the universe to another, but, along with “objects” all other incedent energy would be transported, including visable light from a star it transits to heat energy produced by the interaction of the star and the monolith AND any incedent heat energy the monolith itself produces. A “Black Monolith” that is ALSO a Von Newmann machine(as in 2010:Oddessy Two) would explain EVERYTHING regarding KIC8462852, INCLUDING THE NEW DATA!

I read the conclusion. What I am saying is the bottom range of 100JY seemed arbitrarily high to me, and when I saw figure 2 in the abstract, it didn’t look like anomalous flux to me. I think they picked 100JY as the bottom of their range to be able to write the conclusion you just repeated to me, which doesn’t exclude the possibility of a signal below 100JY, to buy a little more time to get a closer look at what may or may not be a signal at 97JY. I could be wrong, but does that really sound crazy.

Larry:

I have the same question, but I CAN see it being comets. Comet’s near the sun/star have a large, extended cloud of dust and gas around them, plus an equally extended long tail. The tail would be pointing straight out from the star, directly towards us. The optimal orientation to block light from the star during the transit. This paper: http://arxiv.org/pdf/1511.08821v1.pdf attempts to model this, and from what they say, if I understand it correctly, a bunch of comets (10s or 100s) of relatively normal size (10-100 km) can absolutely explain the magnitude of the dimming.

From the dimming paper:

I am not buying this. The dimming (which does look a little shaky when you see the plot) is so completely different in nature and time scale that, to me, even if both real, they most likely are unrelated.

Devil’s advocate time…

We are witnessing a very, very late heavy bombardment, possible initiated by the nearby red dwarf, and as time goes on, with the further breakup of broken up debris, the fragments and dust are obscurring more each century. We’ve only ‘tuned in’ to this long-term, sporadic chapter in KIC 8462852’s ongoing evllution (some centuries data show steady dimming, some centuries data are interspersed with ‘outburst’ events like the one we’ve just observed). The dusty component must be at a suitable distance so as to explain the lack of IR “excess”. Hmm.

Larry: UPDATE: ANOTHER “Alien Megastructure” scenario that fits ALL OF THE CURRENT DATA would be current constructure of a Matrioshka Brain, the most powerful supercomputer EVER CONCEIVED other than a black hole supercomputer! My ONLY issue with this scenario is why would they start construction on the OUTSIDE MATRIOSKH FIRST! The only thing that makes sense is they don’t want to let anyone ELSE KNOW that it IS a Matrioshka Brain by building the INNER component(EASILY DETECTABLE IN THE IR)first.

Interviewed Tabetha Boyajian today. Should be out soon. Thanks t those who submitted questions.