My essay Intensifying the Proxima Centauri Planet Hunt is now available on the European Southern Observatory’s Pale Red Dot site. My intent was to give background on earlier searches for planets around the nearest star, leading up to today’s efforts, which include the Pale Red Dot work using HARPS, the High Accuracy Radial velocity Planet Searcher spectrograph at La Silla, as well as David Kipping’s ongoing transit searches with data from the Canadian MOST satellite (Microvariability & Oscillations of STars), and gravitational microlensing studies by Kailash Sahu (Space Telescope Science Institute).

As it turned out, the choice of earlier Proxima planet hunts as a topic fit in where Alan Boss had left off. Boss (Carnegie Institution for Science) had led off the Pale Red Dot campaign’s outreach effort with a piece on the overall background of exoplanetology (Pale Blue Dot, Pale Red Dot, Pale Green Dot). Whatever the color of the distant world, our tools are developing rapidly, and there is a heady sense of optimism that we have what we need to find Proxima planets, assuming they are there. As Boss puts it:

We now know that nearly every star we can see in the night sky has at least one planet, and that a goodly fraction of those are likely to be rocky worlds orbiting close enough to their suns to be warm and perhaps inhabitable. The search for a habitable world around Proxima Centauri is the natural outgrowth of the explosion in knowledge about exoplanets that human beings have achieved in just the last two decades of the million-odd years of our existence as a unique species on Earth. If Pale Red Dots are in orbit around Proxima, we are confident we will find them, whether they are habitable or not.

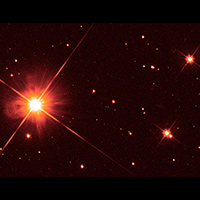

Image: Proxima Centauri (Alpha Centauri C). Credit: NASA, ESA, K. Sahu and J. Anderson (STScI), H. Bond (STScI and Pennsylvania State University), M. Dominik (University of St. Andrews).

Saturday was cloudy, but Sunday offered up a fourth HARPS observation window, activity you can follow on Twitter @PaleRedDot. Let me also remind you that David Kipping wrote up the MOST work just prior to its inception in 2014 (see Proxima Centauri Transit Search to Begin). The latest I have from Dr. Kipping is that 13 days of data in that year were followed by another 30 in 2015. We should have results by the summer of this year. As to gravitational microlensing, we have a second occultation of a background star by Proxima coming up in February. Hope grows that we are getting close to a detection by one method or another.

and after losing a data-point on Saturday(clouds :S), we got a fourth HARPS obs today…yey! building up baseline https://t.co/BsC9M2fKNL

— Pale Red Dot (@Pale_red_dot) January 25, 2016

Proxima Centauri’s Emergence in Fiction

I’ve always been surprised that there wasn’t a greater flurry of interest in Proxima Centauri in early science fiction, given that the closest star to the Sun had just been discovered in 1915. Still, a few odd tales emerged, among the more interesting being Henri Duvernois’ L’homme qui s’est retrouvé (1936), which the indispensable Brian Stableford translated in 2010 as The Man Who Found Himself. Here we have a scientific romance in the grand style, with the journey to Proxima Centauri meshing with time travel and an encounter with the protagonist’s doppelgänger. Stableford has done wonders in reawakening interest in French scientific romance; his labors as translator and critic receive all too little credit.

And then there’s Murray Leinster (Will F. Jenkins), whose story “Proxima Centauri” ran in Astounding Stories in March of 1935. Leinster wanted to treat a journey to another star within a different context. Rather than presenting a dream-like moral tale, he showed a starship (the Adastra) that was capable of getting his characters to Proxima well within a human lifetime. The description is heavy on theatrics, minimal on detail, but it’s fascinating to see writers beginning to consider the sociological problems of long voyages. The Adastra will take ten years to reach its destination, and the crew will deal with mutinies, angst and utter boredom as the price of their ticket.

It’s interesting to see science fiction grappling with how to imagine starflight in this era. Coming out of the age of Gernsback, Leinster wanted solutions more satisfying to the science experimenter of the day than simply ignoring what physics was telling us about time and space. But how to do it? The results demanded giving up one kind of magic (faster than light methods) in favor of another, an authorial sleight of hand that tries to slip one over on the reader. Thus we read about the starship Adastra‘s “tenuous purple flames,” which were actually “disintegration blasts from the rockets” which had lifted the craft into space, and so on.

Anyone who digs up Leinster’s “Proxima Centauri” today will find that despite its reputation in its own time, it hasn’t aged well, and the interest of the effort will be purely an antiquarian one. But we do see the emergence of a greater appreciation of interstellar distances and the problems of staying within known physics in Leinster’s story (available in Asimov’s Before the Golden Age (Doubleday, 1974). Such efforts stand in stark contrast to anemic tales like Frederick Hester’s “Gipsies of Thos,” (Amazing Stories, May 1935) or Leslie Stone’s “Across the Void” (Amazing Stories April-June 1931), both tales that take us to the Centauri stars as if by magic carpet.

Today’s science fiction gives us a Proxima Centauri of considerably more detail, along with a more realistic assessment of the propulsion conundrum that accompanies the voyage. With that detail we’re also given further mysteries about which to speculate. Here’s Stephen Baxter describing the Proxima planet Per Ardua in his novel Proxima (Roc, 2014):

The weather was overcast, muggy, humid. For such a static world the weather had turned out to be surprisingly changeable, with systems of low or high pressure bubbling up endlessly from the south. It was warm in this unending season, always like a humid summer’s day in North Britain, from what Yuri remembered of the weather. But the ColU, ever curious in its methodical robot way, said it had seen traces of cold: frost-shattered rock, gravel beds, even glaciated valleys in the flanks of features like the Cowpat. Evidence that glaciers had come this way in the past, if not whole ice ages. Somehow this world could deliver up a winter.

It’s a winter caused not by axial tilt but by massive eruptions of starspots on Proxima’s face, driving weather patterns on the kind of tidally locked habitable world we may one day find through our ongoing planet hunts. If and when we do find the ‘pale red dot’ around Proxima, writers will continue imagining it, always tightening the detail as new facts emerge, until one day, we can hope, we have robotic or even human emissaries reporting back from the scene.

I have done several paintings of a planet of Proxima. Here is the most successful: http://www.astroart.org/#!Proxima 1989/zoom/cye0/image_1q7p

Alpha A and B may be seen at upper right. In another version (for Challenge of the Stars) our Sun forms an extra star in Cassiopeia.

I definitely remember the “Proxima 1972” image being used in a Patrick Moore book where it was used to depict a hypothetical planet orbiting Betelgeuse!

No, it was a planet of Proxima Centauri — check it! I co-wrote that book with Patrick, not just illustrated it!

We might be thinking of different books then. I’ve managed to find out which book it was: “The New Atlas of the Universe”. I’m not sure what edition though as I don’t have the book any more.

@David Hardy – It looks like you reworked “Proxima” (1972) from an\arlier version by adding the flares and spots. (I’m looking at the image in “Challenge of the Stars”). It is a lovely painting.

Correct — I did so digitally for ‘Futures’, as we had learnt a lot in that 50 years!

There will always be something unremittingly romantic about planets around are nearest neighbour . So close as to be almost touchable. That 4.25 ltyrs sounds so small .

With TESS ,JWST and the ELT infrared imaging spectrographs to come in the next fifteen years or so we will know a whole lot more about such planets and their cool parent stars too. Star spots , coronal mass ejections and stellar flares regardless, it may well yet be that all can be mitigated and we will discover such environs can harbour life ,though admittedly very alien.

Even the ever prescient ,excellent work of Stephen Baxter may be in error when we find that tidal locking is not indeed absolute for habitable zone planets in such systems and that the battle for existence tilts more in favour than imaginined .

Leconte’s work has shown how atmospheres can help resist asynchronous rotation ( Arxiv 2015 ) with core convection found to assist in magnetic field production vitally as well as rotation . It may be that the thicker atmospheres of slowly rotating larger terrestrial planets ,with tectonic replenishment ,efficient heat distribution and and substantive magnetic moments can yet resist being stripped until their stars finally become quiescent . May be.

As I said though, that’s an alien , and perhaps not even necessarily pleasant place to live ( from our perspective at least ) but it might be home for someone.

Paul Gilster: I’m sure you’ve heard all of the rumors surrounding TRAPPIST-1d. Is there ANY WAY that the HOST STAR COULD be Proxima Centauri?

Sorry Harry, I’m not familiar enough with this to comment.

adsabs.harvardedu/abs/2016sptz.prop12126G “Confirming the binary nature of the transit of TRAPPIST-1d.” AUTHORS: Michael Gillon, Julien de Wit, Emmanuel Jehin, Artem Burdanov, and Grootel Van. The paper has been FINISHED, but may have NOT been submitted anywhere yet. I cannot find the preprint on exoplanet.eu, astro-ph, or the Harvared based vox charta.

After doing some more checking, I found out that TRAPPIST-1 is most likely 2MASS J23062928-0502285, which is one of the hottest nearby brown dwarf stars. MOST LIKELY SCENARIO: An ultra-cool brown dwarf regularly eclipses(I do not understand why the word “transit” is used in the title, instead of the word “eclipse”)2MASS J23062928-0502285, but appears to have ANOTHER OBJECT OF UNKNOWN NATURE orbiting it, so BOTH objects cross 2MASS J23062928-0502285 SIMULTANEOUSLY. The BIG QUESTION REMAINING: Does this mystery object transit BOTH BROWN DWARFS?

Ignore my March 18 comment. I WAS WAY OFF! TRAPPIST-1(A?) is an M8 dwarf main sequence star with the following stats: Mass; 0.1 Msun, Radius; 0.15 Rsun, Temperature; 2700K. This M8 star is orbited by an ultra-cool brown dwarf(TRAPPIST-1B?) in an unspecified orbital period with the following stats: Mass; 0.08Msun, Radius; 0.08Rsun, Temperature; 1500K, so it id NOT ultra-cool. NOW, HERE’S THE SHOCKER! The M dwarf APPEARS TO BE ALSO ORBITED BY THREE ROCKY PLANETS of unspecified radii, with unspecified BUT VERY SHORT ORBITAL PERIODS WELL INSIDE THE ORBIT OF THE BROWN DWARF Spitzer has COMPLETED six observations of the “d” planet candidate, and APPARENTLY CONFIRMED the “binary” nature of “planet” d! My IMMEDIATE take on this is that “d”(whatever it WAS) may have been recently RIPPED APART by the COMBINED tidal stress put on it by BOTH the M8 and brown stars! We may be EXTREMELY LUCKY to see it in this configuration JUST BEFORE it forms a ring around the star! Anyone interested in this should CONTINUOUSLY MONITER the Extrasolar visions II website(www.solar-flux.forumandco.com) for updates!

MORE SPECIFIC INSTRUCTIONS: Click “Extrasolar News and Discoveries”. Click “Useful Extrasolar Planet Resources” Borislav, at the RIGHT of the screen. Click “posts”. Click https;//archive.stci.edu/proposal_search.php?id=14493&mission=hst (DO NOT GO TO THIS WEBSITE DIRECTLY because currently there is NO list page for it YET). TRAPPIST-1b has a temperature of roughly 400K. TRAPPIST-1c has a temperature of roughly 250K, VERY CLOSE TO EARTH’S!

I did some calculations overnight. A roughly 400k equilibrium temperature IMPLIES a roughly 2 day orbital period. A roughly 250K equilibrium temperature(which is SIGNIFIGANTLY HIGHER than Earth’s EQUILIBRIUM temperature. Sorry about that)IMPLIES a roughly 4 day orbital period. Assuming a very strong 2 to 1 mean motion resonance THROUGHOUT THE SYSTEM, a PUTATIVE 8 day orbital period would put the d planet(s: See below) in the outer reaches of the habitable zone(i.e., only SLIGHTLY warmer than MARS). The three scenarios I have put forward for the d “binary” are a very large exomoon, a binary planet system, and tidally disrupted planet broken up into two components. There is a FOURTH scenario that I am actually slightly favoring right now: A pair of co-orbiting planets that do NOT ORBIT EACH OTHER! Finally, this is the “leakiest” major planet discovery I have ever seen. It is,in a way, EVEN MORE PUBLIC than PALE RED DOT>

Here are the times for the six Spitzer observations. 2/21/16: 18:24(6:24PM), 3/4/16: 18:58(6:58PM), 3/7/16; 5:20(AM), 3/13/16: 12:54(AM or PM), 3/15/16: 9:25(AM), and 3/18/16: 15:23(3:23 PM). The 5 INTERVALS are APPROXIMATELY as follows: 12 days, 2.5 days, 5.3 OR 6.7 days, 1.8 OR 2.3 days, 3.3 days. Using LOGIC ONLY(i.e. CAVAET: take this with a VERY LARGE grain of salt) the REVISED VALUES for the intervals are: 12, 2.5, 6.7, 2.3, and 3.3 days respectively. Assuming that the FIRST observation was for CALIBRATION PURPOSES(and 3 successive transits were NOT observed, a roughly 3 day INTERVAL between transits can be REASONABLY deduced ASSUMING that these times were the START TIMES for the observations(unfortunately NO info for the DURATION TIMES is available). Assuming the SAME OBJECT was observed, an orbital period of roughly 3 days is IMPLIED, but this FLIES IN THE FACE of my projections for the orbits of the OTHER TWO PLANETS, because Vincent Bourrier CLEARLY STATED that ONLY the orbit of the OUTER PLANET was undetermined! THEREFORE, I revise the orbit to ROUGHLY SIX DAYS, and ASSUME that the observations were made THIS WAY to determine whether there are TWO CO-ORBITING PLANETS on roughly OPPOSITE SIDES OF THE STAR SHARING a roughly six day orbit! If this turns out to be true, science fiction writers will have a field day with it! A six day orbit is right smack in the MIDDLE of the star’s Habitable zone!!

ORIGINAL SPITZER PROPOSAL: “we request a modest amount of time to confirm the binary nature of the transit of TRAPPIST-1d”. LATEST SPITZER PROPOSAL: “the eclipsing binary nature of a nearby ultra-cool dwarf has just been revealed. The aim of this DDT is to investigate this nearby system further through high precision infrared time-seres photometry”. I assume that the “…just been revealed…” part is a RESULT of the previous(above mentioned)Spitzer observations. THIS MUST MEAN that the “…binary natue of the transit of TRAPPIST-1d REALLY MEANS that it transited two DIFFERENT stars, meaning that there is NO NEED for an exomoon, binary planet, or co-orbiting planet to explain the ORIGINAL request. BUT; since this is under “science category: extrasolar planets, it DOES co-incide with Bourrier’s HST proposal based on the “…just discovered three transiting planets around an ultra-cool dwarf…” So what finally appears to be the case is that the now NEAREST(BY FAR)CIRCOMBINARY planetary system is composed of 3 most likeky ROCKY planets, one of which may or may NOT be in the eclipsing binary’s OPTIMISTIC(there is no “COSERVATIVE” in this case due to possibly EXTREME almost constant flaring activity)habitable zone.

One LAST(hopefully) comment before the announcement: SWITCH “ORIGINAL” and “LATEST”. Proposal 12126 was made AFTER the TRAPPIST ground-based telescope revealed that 2MASS J23062928-0502285 was an eclipsing binary SYSTEM rather than a SINGLE STAR! THEN(AND ONLY THEN), the Spitzer Space Telescope DISCOVERED the three transiting planets, of which, TRAPPIST-1b and TRAPPEST-1c transited both stars SEVERAL TIMES, FIXING their orbits! Apparently TRAPPIST-d made two CONFIRMED transits of the primary star, but only one POSSIBLE transit of the other star. So, Proposal 12126G was the FOLLOW-UP proposal to confirm that the OTHER star was INDEED transited by TRAPPIST-1d! This makes a lot more sense, sincr TRAPPIST can detect earth-sized planets around OLNY THE SMALLEST single stars, but Spitzer can detect SUB-EARTH sized stars in very small BINARY SYSTEMS. Thus, the ABOVE Spitzer observations were as a result of Proposal 12126G, NOT Proposal 12126. Sorry for any confusion.

UPDATE: TRAPPIST-1b,c DOUBLE TRANSIT! According to Julie de Wit, “…TRAPPIST-1b and c will transit simultaneously on May 4’th, 2016 at 9H10UT…”. What is not clear is whether they will BOTH be transiting the same STAR at the same time or whether b will transit one star and c will transit the OTHER star at the same time. The wording used indicates that it is Probably the former and not the latter.

L’Homme s’est retrouvé ? Non, c’est L’Homme qui s’est retrouvé.

[voir http://www.lekti-ecriture.com]

Merci! And now fixed in the text.

Just wondering if there will be anymore lensing events for Proxima when the JWST is up and running, not sure if is favourably aligned though.

JWST’s eyes have reached a new milestone.

http://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2016-01/nsfc-btd010716.php

Since December 2015, the team of scientists and engineers have been working tirelessly to install all the primary mirror segments onto the telescope structure in the large clean room at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. The twelfth mirror was installed on January 2, 2016.

“This milestone signifies that all of the hexagonal shaped mirrors on the fixed central section of the telescope structure are installed and only the 3 mirrors on each wing are left for installation,” said Lee Feinberg, NASA’s Optical Telescope Element Manager at NASA Goddard. “The incredibly skilled and dedicated team assembling the telescope continues to find ways to do things faster and more efficiently.”

We HAVE to find the planets circling the Alpha Centauri system because Zephram Cochrane has to invent warp drive!

http://memory-alpha.wikia.com/wiki/Zefram_Cochrane

I always found it interesting/odd that the Alpha Centauri system received relatively little attention and mention in the Star Trek franchise. Perhaps 4.2/4.3 light years were just too local for a warp culture? :^)

And it could not be because the suns were potentially unfriendly to human and humanoid life. Star Trek has plenty of aliens living around stars that were known both back then and now to be rather unpleasant if not outright fatal to most organic life.

Here is a list of some of them complete with finder charts:

http://adirondackastronomyretreat.jarnac.org/images/stlist.pdf

Yes. A big play on 40 Eridani , “Keid”, though. The K1/2 primary star of a trinary system about 16.5 ltyrs away . The alleged home that the same Vulcans who made “first contact ” with Cochrane , hailed from. Just bought the Star Trek Encyclopedia , sad that I am. Wikipedia mentions it too though. Forgotten just how good Jean-Luc P and Catherine Janeway were though watching YouTube recently.

@Paul: What are the smallest masses and/or radii planets that can be probed by the searches you reviewed in today’s excellent post? Also, if as you mentioned in today’s post that every star has on average one planet and most planets tend to be close-in, then wouldn’t the probability of at least one of these searches finding a planet around Proxima be relatively high?

I don’t have the answer ready on that but will be glad to dig it out. Let me float this past Guillem Anglada-Escudé and the Pale Red Dot team.

spaceman, I just received this from Dr. Anglada-Escudé:

“…at the inner edge of the HZ we should reach down to 0.6 or 0.7 Me (P~7 days), around 1 Me at the centre (P~15 days) and about 1.2 Me at the outer edge (P~30 days). The star is certainly active and affects the RVs at 1.5 m/s level, which is what sets these approx limits. If the star is a bit more quiet or more active than usual, then the detection limit can go down or up a bit. The signal we are talking about is between 1.0-2.0 m/s, and must have a period between 10 and 40 days (being ~15 days a bit more likely). I’ll post some plots in short. So square in the HZ but uncertain due to activity (not precission! which is at ~1 m/s level). This also means that things like ESPRESSO might not add much (although we will try for sure). nIR instruments might help a bit in separating activity noise from true Doppler signals. Unfortunately, we are 2-3 years away of having such facility in a southern enough telescope(eg. CARMENES would be ideal, but sits in Spain…).”

I’ll have something soon on transit sensitivity via the MOST data as well.

“METIS” is a first light NIR imaging instrument in the E-ELT. Worth a read . Designers disappointed by the ELT position at relatively NIR unfriendly Cerro-Amazones location. I think they were hoping for somewhere higher , drier and colder .( like the Atacama desert for instance ) . In terms of imaging in the visual it would need a telescope slightly wider than 8m in space to image at that distance and inner working angle ( closeness to star ) , though “EPICS” also on the E-ELT should help but not till 2030.

David Kipping tells me “…our expected best sensitivity will range from 0.6 to 1.0 Earth radii across the range of 0.5 – 10 days, corresponding to something like 0.2 to 1.0 Earth masses.” But he adds the warning that “these are back of the envelope numbers, we have not completed our full sensitivity curve analysis yet.”

At https://palereddot.org/intensifying-the-proxima-centauri-planet-hunt/

Paul Gister writes

“Any habitable planet around it should produce a relatively deep transit signature in the star’s light curve, because the size of the planet in relation to the star is significant as opposed to small worlds around much larger G- or F-class stars. For the same reason, the likelihood of a transit alignment is enhanced.”

To be more precise, the transit probability for an “habitable” planet

(i.e. with a temperature Tpl = 300K) is not a matter of stellar size

but of stellar temperatute T*, since the transit probability is then just

p = 2(Tpl/T*)^2.

Excellent. Thank you for that clarification, Dr. Schneider! Always a pleasure to see you here.

It’s funny to see this expressed in terms of temperature rather than size but it illustrates perfectly the close entwinement of the two for main sequence stars.

On their Facebook page there’s this little teaser:

Pale Red Dot is an exciting scientific and outreach program attempting to discover Earth-like planets around Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Solar System.

After years of data acquisition by many researchers and teams, there is a signal which may indicate the presence of an Earth-like planet. The Pale Red Dot project will carry out further detailed observations attempting to confirm the existence of the planet.

Based on current bolometric luminosity measurements of 0.0017 solar luminosity and the mass of 0.123 solar, that means the Earth-Insolation-Orbit is at 0.041 AU and has a period of 8.7 days. Will be interesting to see what signal they glean from their observations.

I was lucky enough to speak to Jim Kasting about this a while back having had a bit of a sneak preview . He reckoned this planet would receive about 0.37 Earth equivalent insolation , which his Penn State team’s latest calculations put at about 2/3 of the way out in a Habitable Zone . Not too bad and at about 1.25 Re ( admittedly with no official mass) more than 2 Earth mass if equivalent density so better at gravitationally holding onto an atmosphere of note . That might in turn have helped it resist synchronisation of its orbit ( Leconte et al ) and with enhanced convection in its core ( Morales -Lopez ) to have produced a meaningful magnetic field for further protection. At that distance a good bit of Greenhouse heating would be very welcome ! A lot of extrapolation admittedly , but who cares? It’s Proxima.

I think this excellently illustrates not just how tight the habitable zones are around smaller ( cooler -Sorry Dr S) stars but also how narrow they are too. Making discovery and classification very difficult in terms of future direct imaging and demonstrating why large aperture telescopes in space and on the ground are so important .

Compared too the equivalent in say a late F dwarf it’s really quite stark. Not many of the latter in the stellar neighbourhood unfortunately even allowing for their much greater rarity as a whole. All illustrating why M dwarfs , even small M dwarfs like Proxima, attract so much interest as there are just so many of them. It’s a strange thing that the nearest star to Earth is not even close to being visible to the naked eye.

An 8.7 day orbit…hmmm… With a little luck, maybe a planet in or near such a Sol(ar)-insolation orbit around Proxima could be in a situation similar to that of Mercury, where the planet isn’t tidally-locked to forever face Proxima, but is in a 2/3 rotation/orbital period resonance. That would result in a day about 5.8 Earth-days long, which might enable life-friendly temperatures, provided that the planet retains a sufficiently dense atmosphere.

The most likely orbit “signal” is about 18 days as I understand it and was the figure for which 0.37 insolation worked out.

Venus is a better example than atmophereless Mercury of the effect a thick atmosphere can have on synchronicity resistance. A 90 Bar CO2 dominated example is no one’s idea of habitable , yet is so thick that it not only reverses tidal synchronisation but gives rise to a retrograde orbit.

Paul: I found the answer on my own. It is:NO! That’s because TRAPPIST IS the ground based survey that failed to turn up any planets larger than 1Re. As for the PUTATIVE TRAPPIST 1d detection:NOTHING HERE, because it would be a bit OFF-TOPIC, but please “google” TRAPPIST-1d, and click on the “SPITZER” listing, to see if it may be WORTHY of a future posting.

Well, now you’ve got my curiosity going, Harry. I’ll check into it. Thanks.

There’s some stuff about this one on the Extrasolar Visions II forum. Mostly rumours so far, but potentially could be quite interesting. From what I can see we need to be patient and wait for the data analysis to be done, it may well turn out not to be as exciting as it’s being made out to be.

This is the latest Pale Red Dot tweet: “Analysis of #palereddot data has been long and intense> A few things to polish but conclusions look convincing…at least to us.” MY TAKE ON THIS: They now appear to know FOR CERTAIN whether there are or are not ANY earth mass planets orbiting in the habitable zone of Proxima Centauri in either edge-on or near edge-on orbits!

An even NEWER tweet appeared today: “Now the review process will begin. First we submit to a scientific journal and the editors send it to other scientist to review our methods.” In other words: THE PAPER HAS BEEN WRITEN! I pray that a pre-print will appear on arxiv(and most likely on exoplanet.eu ALSO)SOMETIME NEST WEEK,but if it is a POSITIVE result, it will ALMOST CERTAINLY BE EMBARGOED!

Paul Gilster: PALE RED DOT IS BACK ONLINE and their Twitter account is up and functioning! Please check it out ASAP!!!

Don’t worry, Harry, I’m in contact with the Pale Red Dot team and will report on any news when I can.