Knowing what comets are made of — dust and ice — only begins to answer the mystery of what is inside them. A compact object with this composition should be heavier than water, but we know that many comets have densities much lower than that of water ice. The implication is that comets are porous, but what we’d still like to know is whether this porosity is the result of empty spaces inside the comet or an overall, homogeneous low-density structure.

For answers, we turn to the European Space Agency’s continuing Rosetta mission. In a new paper in Nature, Martin Pätzold (Rheinische Institut für Umweltforschung an der Universität zu Köln, Germany) and team have gone to work on the porosity question by analyzing Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, around which Rosetta travels. It’s no surprise to find that 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is a low-density object, but an examination of the comet’s gravitational field shows that we can now rule out a cavernous interior.

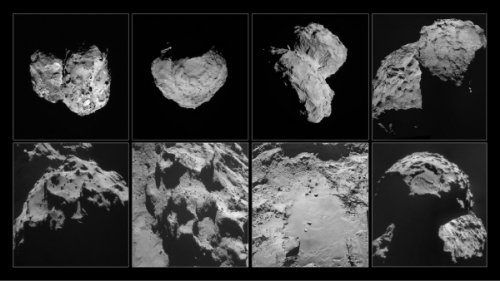

Image: These images of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko were taken by Rosetta’s navigation camera between August and November 2014. Top row, left to right: Comet pictured on 6 August 2014, at a distance of 96 km; 14 August, at a distance of 100 km; 22 August, at a distance of 64 km; 14 September, at a distance of 30 km. Bottom row, left to right: Comet pictured on 24 September, at a distance of 28 km; 24 October, at a distance of 10 km; 26 October, at a distance of 8 km; 6 November, at a distance of 30 km. Copyright: ESA/Rosetta/NAVCAM, CC BY-SA IGO 3.0.

This is tricky work performed using Rosetta’s Radio Science Experiment (RSI) to examine just how the Rosetta orbiter is affected by the gravity of the comet. And just as we do when measuring the tiniest motions of distant stars to search for planetary companions, the researchers use Doppler methods to make the call, measuring how signals from the spacecraft change in frequency as Rosetta is affected by the comet’s gravity. In this way we can build up a picture of the gravity field across the comet while working to rule out other influences.

“Newton’s law of gravity tells us that the Rosetta spacecraft is basically pulled by everything,” says Pätzold, the principal investigator of the RSI experiment. “In practical terms, this means that we had to remove the influence of the Sun, all the planets – from giant Jupiter to the dwarf planets – as well as large asteroids in the inner asteroid belt, on Rosetta’s motion, to leave just the influence of the comet. Thankfully, these effects are well understood and this is a standard procedure nowadays for spacecraft operations.”

As this ESA news release explains, the team wasn’t through even after compensating for all these other Solar System bodies. Also to be considered was the pressure of solar radiation and the gas escaping through the comet’s tail. Rosetta uses an instrument called ROSINA to measure the flow of gas past the spacecraft, allowing its effect to be measured. No sign of large internal caverns emerged from the analysis.

We’re lucky with 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in that the comet turned out not to be round, as ground-based observations had previously suggested. As we’ve gotten to know the comet, its distinctive double-lobed shape has proven not only visually interesting but scientifically helpful. The twin lobes mean that differences in the gravity field are more pronounced and easier to study from the 10 kilometer distance Rosetta had maintained for reasons of safety. With variations in the gravity field already showing from 30 kilometers out, the much richer measurements from 10 kilometers could proceed.

The result: Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko is found to have a mass of slightly less than 10 billion tonnes. By using images from Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera, the team was able to model the comet’s shape so as to produce a volume of approximately 18.7 km3, yielding a density of 533 kg/m3. Given this and the lack of large interior spaces, we can look at the comet’s porosity as a property of its constituents. Rather than a compacted solid, comet dust is more of a ‘fluffy’ aggregate of high porosity and low density.

Image: Rosetta from Earth, in an image taken by Paolo Bacci on February 6, 2016 from San Marcello Pistoiese, Italy.

Keep your eye on Rosetta. In September, the spacecraft will be brought in for a controlled impact on the surface, a challenging navigational feat for controllers at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) in Darmstadt, Germany. Closing on the comet will allow the gravity observations to continue at a much higher level of detail, making it possible for caverns only a few hundred meters across to be detected, if indeed they are there at all.

The paper is Pätzold et al., “A homogeneous nucleus for comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko from its gravity field,” Nature 530 (04 February 2016), 63-65 (abstract).

So basically the density of packed snow. So the classic description of “dirty snowball” is apt.

I’m very impressed with the gravity analysis. Will Dawn be able to do something similar for Ceres, sufficiently to infer interior structures, e.g. subsurface seas?

Does this mean that someone out there at one time was having the mother of all snowball fights? And are they coming back to pick up where they left off?

:^) :^)

Hope not… not exactly the snowball equivalent of Queensbury Rules when they’ve packed so much dirt and stones into their snowballs, eek! ;D

So, what keeps it from collapsing into a more spherical shape?

Gravity. Or rather, not enough of it. More mass is needed to crush inward and reach a stable, quasi-spherical shape.

The gravity on these small objects is very, very small so the local strengths of the material grains prevent true hydrostatic equilibrium, they also can rotate a fair bit so that does not help matters either.

Now every time I see a comet I think materials for a colony, anyone else?

After posting the previous comment I realized the rotation lessens the “crushing” effect of gravity quite a lot (in this case). You could pretty much jump off the 67P, I think..? But still, I guess the thing is not completely fluffy/fluid.

Slightly off-topic, I asked Wolfram Alpha what is the gravitational binding energy of Phobos and supposedly it is about 100MT of TNT equivalent. With a Tsar Bomba using uranium tamper around the third stage(s) we should be able to blow Phobos to pieces and create rings around Mars!! (Undoubtedly there would be some energy losses but I guess they would be compensated somewhat by Phobos’ orbit inside the Roche limit..)

If we really really wanted to, we could disperse a very large asteroid or comet.

Off-topic, but also dealing with interiors, those of earthlike planets:

Earth-like planets have Earth-like interiors

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/02/160208124245.htm

@ljk

Had the Greeks or Norsemen had known about the true mature of comets, I’ve no doubt that this might well be an explanation woven into their mythology.

;)

Didn’t they think aurorae were the gods having a literal clash of the Titans?

I don’t think the aurorae were mentioned at all in Old Norse tales. Winter was associated with death so maybe they didn’t see it that often. The tales I’ve heard all seem to stem from more modern, romantic assumptions than facts. For example, the aurora has been attributed to the ghosts of maidens, the reflections off Valkyrie armour, or, more commonly, a display from their god Ullr. I haven’t been able to see if the association with their goddess Freya is truly Norse or another ‘modern’ assumption (modern = post 1300 CE).

Takes nothing away from their splendour though!

Fluffy or not, even relatively small comets can still pack a wallop. Just ask Jupiter…

http://www.scientificamerican.com/article/s19-the-comet-that-battered-jupiter-and-shook-congress/