Landing on a small object in the Solar System isn’t easy. Witness the Philae lander, which traveled to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko as part of the European Space Agency’s Rosetta mission. Philae ‘landed’ on November 12, 2014, having to deal with a malfunctioning thruster along the way. Upon arrival at the surface of the comet, Philae was to have fired anchoring harpoons to steady itself on the surface, but after a dramatic seven-hour descent, the harpoons failed to fire.

Thus the lander did touch down at the initial landing site, called Agilkia, but then bounced to a new site — Abydos — about a kilometer away. Even now, we’re not sure just where Philae is despite imagery from the orbiting Rosetta. What ESA has told us, however, is that the lander evidently made contact with the comet four times during an unplanned for two-hour additional flight across the surface. During the process it grazed the rim of a depression called Hatmehit on its way to its resting place at Abydos.

Image: A series of 19 images captured by Rosetta’s OSIRIS camera as the Philae lander descended to the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on 12 November 2014. The timestamp marked on the images are in GMT (onboard spacecraft time).

Credit: ESA/Rosetta/MPS for OSIRIS Team MPS/UPD/LAM/IAA/SSO/INTA/UPM/DASP/ID

I often marvel in these pages at the ability of researchers to pull data out of malfunctioning spacecraft, going back to missions like Mariner 10, which was saved by using its solar panels to steady the spacecraft for all-important navigation fixes. With Philae we see another case of controllers doing everything they can to mitigate a bad situation. In its case, despite a landing that was anything but by the book, the lander completed numerous science measurements even as it bounced along its way to the Abydos site.

We learn in this ESA news release that 80 percent of the initial planned scientific activities were completed despite the bumpy arrival. For 64 hours after the separation from Rosetta, Philae took numerous images from above and on the cometary surface, studying organic compounds and providing data on the surface properties of 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko.

You’ll doubtless remember the rest: The lander was receiving insufficient sunlight to charge its secondary batteries, making data collection a race against the clock while the primary battery drained. Philae lapsed into hibernation on the 14th of November, 2014, though controllers had hopes that as the comet moved toward perihelion in August of 2015, the lander might awaken. And indeed on June 13, Philae resumed telemetry transmissions, with data showing that it had actually come back to life on April 26 but had not been able to send signals until June 13.

Contact with Philae in following weeks included seven intermittent links with Rosetta, the last coming on the 9th of July. Rosetta itself had to back off from 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko because of increased gas and dust activity as the comet warmed. Recently the activity levels have fallen enough to allow Rosetta to close to within 45 kilometers, but despite repeated passes over the landing area, no subsequent signal from Philae has been detected.

“The comet’s level of activity is now decreasing, allowing Rosetta to safely and gradually reduce its distance to the comet again,” says Sylvain Lodiot, ESA’s Rosetta spacecraft operations manager. “Eventually we will be able to fly in ‘bound orbits’ again, approaching to within 10-20 km – and even closer in the final stages of the mission – putting us in a position to fly above Abydos close enough to obtain dedicated high-resolution images to finally locate Philae and understand its attitude and orientation.”

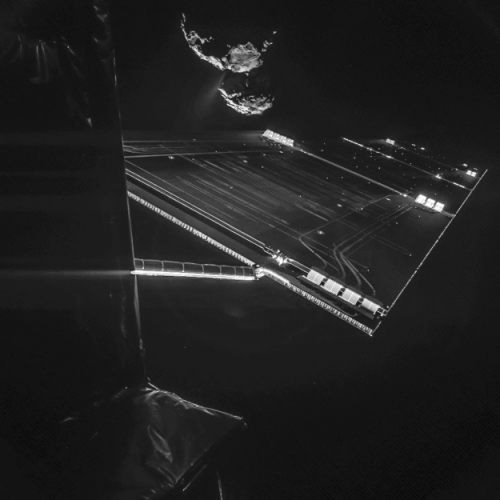

Image: Using the CIVA camera on Rosetta’s Philae lander, the spacecraft snapped a ‘selfie’ at comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko from a distance of about 16 km from the surface of the comet. The image was taken on 7 October and captures the side of the Rosetta spacecraft and one of Rosetta’s 14 m-long solar wings, with 67P/C-G in the background. Two images with different exposure times were combined to bring out the faint details in this very high contrast situation. The active ‘neck’ region of 67P/C-G is clearly visible, with streams of dust and gas extending away from the comet. Credits: ESA/Rosetta/Philae/CIVA.

Hopes of contacting the lander have faded given conditions on the surface, where dust may well be covering Philae’s solar panels. Moreover, there is no reason to think that Philae is in the same orientation or even location that it was in November of 2014, given the outflows of gas and dust the comet experienced last summer. Now 350 million kilometers from the Sun and on its way back out toward the outer system, the comet is at temperatures below the lander’s ability to operate.

Rosetta, despite all this, will keep listening for signals all the way in as it moves toward the comet for a landing in September. The odds get longer with each passing day:

“The chances for Philae to contact our team at our lander control centre are unfortunately getting close to zero,” says Stephan Ulamec, Philae project manager at the German Aerospace Center, DLR. “We are not sending commands any more and it would be very surprising if we were to receive a signal again.”

If ESA were planning this again with 20:20 hindsight, I wonder if they would have considered an RTG power source rather than solar panels for the power supply? Or would they go for a more robust anchoring mechanism to compensate for a landing failure?

There are lessons here for future robotic asteroid miners.

As far as I know ESA doesn’t have RTGs. They’re stuck with solar panels.

Deciding between the two isn’t an obvious choice. I think designing a more robust anchoring system would require more information about the surface qualities of the asteroid or comet than would be available before landing.

How about landing many mini-landers that would be battery powered but also had power beamed to them from the orbiting craft?

Perhaps, some day, another civilization (a descendant or ours?) will notice this artifact, and wonder.

If they find the Rosetta orbiter, they will encounter a disc etched with 1,500 human languages, an invaluable discovery:

http://sci.esa.int/rosetta/31242-rosetta-disk-goes-back-to-the-future/

and here:

https://howwegettonext.com/from-ancient-egypt-to-comet-67p-transmitting-languages-into-the-distant-future-70ed0b871a48#.q6ny12l8d

All of human knowledge and information should be preserved in deep space. Here is one new method:

http://phys.org/news/2016-02-eternal-5d-storage-history-humankind.html

I hope Heath Rezabek is paying attention for his ideas on long term storage to preserve civilization.

Even in failure to anchor the probe gave an enormous amount of information, in the springiness of the comets surface implying a heated and cooled crust that is quite dynamic.

Now I am not surprised by the activity at the neck of the comet which looks to be a contact binary comet. The regolith’s of the two have collected in the middle and are highly disrupted and prone to heating and subsequent out gassing, the mystery is how they got together in the first place.

typo: “350 kilometers from the Sun”

Thanks for catching that! Now fixed.