I will admit to a fascination with Pluto’s moon Charon that began even before it was discovered. Intrigued by the most distant places in the Solar System, I had always imagined what the view would be like from a tiny moon circling Pluto. At the time, we didn’t know about Charon, so my vantage point was more like what we now know Kerberos or Styx to be. Then my interest tripled when the sheer size of Charon became known. A large moon was truly a world of its own, and Charon rose in my estimation to rival my other most intriguing moon, Neptune’s Triton.

Now we have word that Charon may once have had an internal ocean, still further evidence of the intricacy of objects in or near the Kuiper Belt. In Charon’s case, something intriguing is shown by a study of the surface, one side of which New Horizons saw during the July 2015 flyby. What appears to be a series of tectonic faults that show up in the form of ridges, scarps and valleys reveals a surface that has to have been stretched over time.

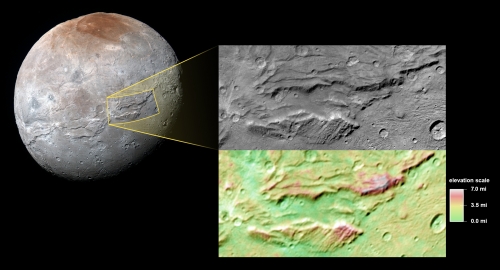

Image: Charon from New Horizons. This image was obtained by the Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) on New Horizons. North is up; illumination is from the top-left of the image. The image resolution is about 394 meters per pixel. The image measures 386 kilometers long and 175 kilometers wide. It was obtained at a range of approximately 78,700 kilometers from Charon, about an hour and 40 minutes before New Horizons’ closest approach to Charon on July 14, 2015. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute.

Remember that on the young Charon, radioactive elements and residual heat from formation could have kept the outer layer of water ice warm enough to melt, creating an ocean beneath the outermost ice crust. Cooling over time would have caused the ocean to freeze and expand, pushing the surface outward to produce the topography New Horizons encountered.

Have another look, then, at the image, which is taken from this JHU/APL news release. At the top right, you can see the feature called Serenity Chasma, which is actually only a part of an equatorial belt of chasms that runs about 1800 kilometers, reaching depths of up to 7.5 kilometers. The lower part of the image provides color-coded topography of the same area. Researchers on the New Horizons team believe the image shows evidence of liquid water that has refrozen over the aeons.

Last spring before the New Horizons flyby I briefly mentioned Stephen Baxter’s “Gossamer.” It’s a short tale in his highly recommended 1997 collection Vacuum Diagrams, following two explorers who have made a forced landing on Pluto only to discover a bizarre form of life that looks like snowflakes. Here’s the relevant bit:

Lvov caught glimpses of threads, long, sparkling, trailing down to Pluto — and up toward Charon. Already, Lvov saw, some of the baby flakes had hurtled more than a planetary diameter from the surface, toward the moon.

“It’s goose summer,” she said.

“What?”

“When I was a kid…the young spiders spin bits of webs, and climb to the top of grass stalks, and float off on the breeze. Goose summer — ‘gossamer.'”

“Right,” Cobh said skeptically. “Well, it looks as if they are making for Charon. They use the evaporation of the atmosphere for life… Perhaps they follow last year’s threads, to the moon. They must fly off every perihelion, rebuilding their web bridge every time…”

Baxter paints a living, interacting system that draws resources from both worlds. Nothing like that in the New Horizons imagery, of course, but plenty of food for thought as we consider the resources of water ice and potential sub-surface oceans even this far from the Sun. Whether any liquid water could survive through the decay of radioactive elements deep within a Kuiper Belt object is debatable, but Charon appears to be showing us what happens when such an ocean finally freezes, its surface ripped apart to create today’s massive chasms.

Video Lecture: Geology After Pluto

Published on Feb 19, 2016

Jeff Moore is the lead of the New Horizons Geology Team. He will talk about the discoveries made by the New Horizons mission on the fascinating fly by of the dwarf planet Pluto.

Video here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JEvnUiEUZ8c&feature=youtu.be&utm_content=bufferc9e23&utm_medium=social&utm_source=plus.google.com&utm_campaign=buffer

Tiny nitpick: Vacuum Diagrams was first published in 1997, and the title of the story, as published in that collection, is “Gossamer,” though “Goose Summer” would be an equally appropriate and perhaps more interesting title.

You’re certainly right on the title! I changed it in the text above. The 2009 is indeed a reprint edition, as I see upon checking. I’ll change that, too.

When you suggest that Charon’s oceans were made liquid by radioactive decay, is that in contrast to the heat from any collision with Pluto, or from heat caused when Charon and Pluto synchronized their rotations?

Tom, yes, decay of radioactive materials when Charon was young is something the New Horizons team speculates about, but it is only one possible source. As Michael noted here, there may be some tidal energy being pumped in, or heat from early in the moon’s formation.

The many orbiting moons may be helping pump tidal energy into the moons interior.

I consider Pluto-Charon to be a binary planet. I think we shouldn’t under-rate the potential of the dynamics of tidal pulling between the two components to contribute to subsurface heating of oceans, or at least lakes, at both objects. Such might be more likely during perihelion.

Now that the two worlds are locked, wouldn’t tidal heating stop? Maybe it once was partly responsible for heating a subsurface liquid body, but not now, would it?

I’m somewhat confused on that point. I can understand two objects of equal mass orbiting in perfect circles (perhaps differing in density and thus size) around their common barycenter; in which case I would expect neither to impart much in the way of forces to the other which would contribute to interior heating.

However, I don’t understand how two objects which differ in mass can avoid imparting forces to each other. (I did have to look up the eccentricity of Charon’s orbit, which is nil.)

I’m thinking of centrifugal force, such as when a parent holds a child up and spins around on his or her heels, and the child seems to be ready to fly away. Of course with planetoids, the force of gravity keeps that in check. But wouldn’t this have an effect on the internal structures of the planetoids?

Thanks in advance for clarifying this; anyone.

Both worlds are experiencing freefall, they are falling towards each other but due to the warping of space-time by their masses they can’t until the orbital momentum is removed. The planet/moon must undergo some deformation resisted by gravity and the mechanical makeup of the object due to the gravity gradient. As can be seen in this gifv the process is well seen to have affected other moons in orbit around Pluto.

http://i.imgur.com/e7Yu2C9.gifv

As for the heating source I wonder if the dust on the moons surface is forming an insulating layer on the surface, dust in a vacuum is very insulating. Perhaps this dust is insulating the residual heat of formation and orbital eccentricity dampening energy, the other moons are too small on reflection to have any great effect. There is also strong evidence of ammonia which is a powerful antifreeze in Pluto, therefore it is likely on Charon as well.

Paul from the images you could be forgiven for thinking they are pictures from Mar’s former river channels!

I agree. Being stably locked and having no eccentricity, Charon’s orbit will not cause tidal heating on either Charon or Pluto. The other moons are too small to make have a significant effect, I think.

Interesting article on dusts insulating properties, 1m of very lightly compacted dust is as insulating as 1km of ice. Given a few hundred meters of it and it becomes quite an effective thermal cap on small worlds like Charon and Pluto.

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1101.2586.pdf