Rama is a name that resonates with science fiction fans who remember Arthur C. Clarke’s wonderful Rendezvous with Rama (1973). The novel depicts a 50-kilometer starship that enters the Solar System and is intercepted by a human crew, finding remarkable and enigmatic things that I will leave undescribed for the pleasure of those who haven’t yet read the book. Suffice it to say that among Clarke’s many fine novels, Rendezvous with Rama is, along with The City and the Stars, a personal favorite.

What a company called Made in Space Inc. has in mind is something different than Clarke’s vision, though it too evokes names from the past, as we’ll shortly see. Based in Mountain View, CA the company is embarking on an attempt to turn asteroids into small spacecraft that can move themselves to new trajectories. RAMA in this case stands for Reconstituting Asteroids into Mechanical Automata, and it proceeds by putting ‘Seed Craft’ on asteroids that will use materials found on the surface. This is the kind of in situ resource utilization (ISRU) that Ian Crawford discussed in his essay in these pages last Friday.

A suitably modified asteroid could take itself to the nearest extraction point for human mining, while the seed craft could be sent on to another asteroid. Build the system right, Made in Space believes, and you can do away with at least some of the human control needed for space operations. 3-D printing plays a big role here, no surprise given the company’s background in providing the first such printer (to the ISS in 2014) that can function in zero-g. Our friend Jon Lomberg worked with Made in Space to create a ‘Golden Plate’ commemorating the first space manufacturing operation, now attached internally to the functioning space printer.

That name from the past I mentioned above is Dandridge Cole, an aerospace engineer, former paratrooper and futurist whose death in 1965 at the young age of 44 cost the space community one of its true visionaries. Cole had plenty of ideas of his own on moving asteroids, but in his case, the idea involved more than robotic transfer into a new orbit. Much more. Why not, thought Cole, actually hollow out an asteroid to create an internal habitat? Here’s how Alex Michael Bonnici described Cole’s idea in a tribute written in 2007:

In 1963, Cole wrote Exploring the Secrets of Space: Astronautics for the Layman with I. M. Levitt. In this book they suggested hollowing out an ellipsoidal asteroid about 30 km long, and rotating it about its major axis to simulate gravity. By reflecting sunlight inside with mirrors, and creating, on its inner surface, a pastoral setting an asteroid could be transformed into a permanent space colony. Cole and Cox also envisioned that asteroids would provide the raw materials to form the basis of a spacefaring civilization. And, that asteroidal materials would also serve terrestrial needs. In their view these materials could be transported using mass drivers or linear motors. Cole’s work largely presages that of Gerard K. O’Neill by more than a decade.

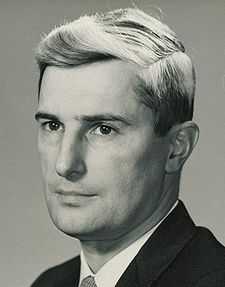

Image: Aerospace engineer and futurist Dandridge Cole, who coined the term ‘macro-life’ to refer to human colonies in space and their evolution. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

Hollow asteroids are an idea familiar to science fiction fans, who will have encountered the trope in various short stories and perhaps in George Zebrowski’s 1979 novel Macrolife. The name is carefully chosen because Cole used ‘macro-life’ to describe future human evolution within space habitats like these, a development he thought would involve a life-form incorporating technology and intimately synchronized with its environment. Putting large colonies of hollow asteroids into play would ensure our species’ survival while allowing us to progress, he believed, beyond dangers like nuclear proliferation and population pressure.

Here’s Cole in 1961, from an essay called “The Ultimate Human Society”:

This concept of a new life form which I call Macro Life and Isaac Asimov calls ‘multiorganismic life’ serves as a convenient shorthand whereby the whole collection of social, political, and biological problems facing the future space colonist may be represented with two-word symbols. It also communicates quickly an appreciation for the similar problems which are rapidly descending on the whole human race. Macro Life can be defined as ‘life squared per cell.’ Taking man as representative of multicelled life we can say that man is the mean proportional between Macro Life and the cell, or Macro Life is to man as man is to the cell. Macro Life is a new life form of gigantic size which has for its cells individual human beings, plants, animals and machines.”

Arthur Clarke liked the notion enough to call Zebrowski’s novel ‘a worthy successor to Olaf Stapledon’s Star Maker,’ which had been a major influence on Clarke and most of his contemporaries. As to the notion of moving asteroids about, an early treatment was Robert Heinlein’s ‘Misfit,’ in which an asteroid is moved out of the main belt to an orbit between Mars and the Earth. This one made its appearance in the November 1939 issue of Astounding Science Fiction, and would hardly be the last asteroid-themed tale. A more modern take shows up in Larry Niven’s Known Space stories and the memorable ‘Belters.’

Image: An engineered asteroid from without and within. Illustrator Roy Scarfo worked with Cole on the 1965 book Beyond Tomorrow. Credit: Roy Scarfo.

We’ve come a long way from Made in Space and their plans to move asteroids through ‘seed craft’ and in situ resource utilization, but what I find exciting here is the synergy between some of these ideas from the past and the conceptual studies Made in Space is performing, with help from NASA’s Innovative Advanced Concepts Program. Asteroid mining gives us a route forward as we contemplate infrastructures within the Solar System, building, we can hope, toward a society comfortable working in deep space and continuing to explore.

It is a very inefficient way to use the mass of the asteriod to make a colony ship. If the asteriod is rotated to generate 1 g the dust and loose rocks would more than likely fly off into space.

Hollowing out an asteroid and living inside the result is not a good idea for two reasons:

* First, it is fraught with peril, because natural objects will likely have fractures and inclusions that are weak points if you pressurize it.

* Second, you want to collect solar energy from a much larger area than the asteroid itself, and use the entire surface of the asteroid as a mine in order work at a reasonable pace. A large underground copper mine, El Teniente in Chile, excavates 100,000 tons of ore per day. A 12x12x30 km ellipsoidal asteroid has a mass of 3 to 16 trillion tons, and would therefore take 88,000 to 440,000 years to hollow out at that rate.

The largest US surface coal mine moves 500 million tons/year of material from a ~1 km^2 working area. Since the asteroid’s surface area is 1000 times larger, in theory you can mine 50 billion tons/year, and consume the asteroid in 60-300 years.

What you would do with all that material is convert it to multi-layered engineered shells around the original asteroid which you can pressurize and occupy. Metallic asteroids would be a good source for the shell materials, but not for oxygen and water. So in practice you would likely not attack one big asteroid, but rather gather materials from a variety of sources. Multi-layered habitats are safer than single pressure shells because a hole doesn’t let all the air out. Holes can be caused by random undetected meteoroids or by accidents.

I agree that hollowing out an asteroid might not be so much easier as mining it entirely and processing it entirely to build proper hull. In Rendezvous with Rama, the ship isn’t a hollowed-out asteroid but an almost perfect cylinder, probably made by consuming an entire asteroid or several types of asteroids and processing all the material in it to make the shell. I also think this will be safer and in fine more practical than hollowing out the asteroid and use its natural shell, especially given the fact that the outer layers of an asteroid are likely to be a loosely accreted rubble pile and can even be porous (cf. Hyperion, Saturn’s moon).

If the asteroid’s surface is rich in water it can make for a good radiation shield and water reservoir, but an airtight and multi-layered internal hull will be required anyway

Keep in mind too, if just capturing an astroid for the purpose of hollowing out as some kind of interstellar craft might be superior to any man made craft we could devise at this point in time. This ‘ship’ would have to be quite a bit smaller than what you are talking about, and would have to be thoroughly tested for the rigors of space travel, but the huge advantage here is the natural protection from radiation due to the composition of the asteroid itself. Asteroids watet commpsition had already been matched more closely than that of comets, and all that water is trapped within crystals in the asteroid. It would take someone smarter than myself to figure out how thick the outer walls would need to be, and obviously the surface would have to include solar panels, and the interior would be of man made construction, but it could work. Probably bettet than the one way mission to Mars we are spending Billions on right now.

I’m not sure I’ve went a decade without rereading “Rendezvous with Rama” since I first read it. A great yarn!

I also loved those old visions of spinning up and pressurizing hollowed out asteroids. I have to say though, given what we now know it seems very problematical. It would seem more likely that the pressurized container would be spinning freely inside the mined out asteroid, or more likely a shaped up slag heap. This would provide it with low value shielding.

Or comets. A small seed spacecraft is sent to catch up with one which comes from the outer reaches of the Oort cloud. Deployes a huge solar sail as the comet grazes the Sun and then constructs a roving water ice fuel factory and a rocket engine to propell it towards some interstellar target. Over the years billions of tons of rocket fuel would be available. Rocky useless parts of the comets could be ejected early on, using the melting power of the Sun during the near passage of it, to lower the mass to be propelled.

I think comets with neat 1 eccentricity pass by Earth at about 70 km/s typically. Twice the launch speed of New Horizons, so it is not unreasonable to catch up with one. Rosetta caught up with one, although it had been put in a slow orbit by Jupiter, which a cometcraft might use to instead accellerate. Small mass launched to it, huge fuel mass onboard, that’s the simple idea.

Conceptually, hollowing out or inflating an asteroid seems to make a lot of sense. Why not use all that mass already in space. However it may prove hard to ensure hull integrity of such construction methods, especially if spun up to provide artificial g inside. KSR indicates this in his novel 2312, where an asteroid habitat fails due to a problem in the hull.

I am also starting to think that these pastoral interiors, perhaps made most famous by the paintings of O’Neill’s space colony interiors, is a romantic vision, perhaps reflecting ancient desires of Heaven above Earth. I suspect the reality will be far more like Corey’s Expanse stories, gritty tunnels in rocks that might be the space equivalent of a favela. This approach maximizes living area and seems far more resistant to any sort of failure, especially a decompression. Given that half the planet already lives in cities, by the time these asteroids are populated, most humans will already be comfortable living in vast artificial constructions with just small manicured areas of greenery.

I also think that asteroid habitat construction will require a lot more than just drilling and spinning. I suspect that high tensile materials will be needed to ensure that the structure doesn’t fly apart, and it wouldn’t surprise me if the asteroid materials aren’t remanufactured to provide engineered material of metals, ceramics and plastics for both hull and interiors.

In terms of sheer lebensraum, asteroids alone could provide vastly more living space than the surface of planets, although this benefit might be less advantageous if planetary surfaces are remade as multiple levels as part of cities that would dwarf even the megalopolises of today.

Consider the NI battlestations in John Ringo’s Troy Rising series. Not necessarily the scale (kilometer thick walls) but rather the methods used in their construction.

This theme was also explored in the 1968 season 3 Star Trek episode titled

“For the World is Hollow and I Have Touched the Sky”.

A nifty Idea But I agree some of the caveats from Mr Eder.

If the rock is solid, that’s going to require a lot of energy to

melt and you will have to redeposit most of the debris some where

and there will be a lot of debris. (you wont be able to use it all as contruction material)

Rocky Asteroids only solve part of the problem, and it’s not clear to me why if you have enough energy to nearly melt all of the bulk matter, you could not instead reshape it to a proper ferris wheel type spaceship, and strap some

engines on to it.

For interstellar operations, I much prefer Very Dirty Snowballs of the size

several times our largest sporting venues.

Like for instance the core of older comets that have settled into

orbit beyond the snow line. If they have Ammonia & H20 with organic

compounds, so much the better With other minerals in the dirty ice ball, you would likely have 98% of the materials to have viable colony ship.

,

I agree completely – the energy costs of digging out and extracting valuable elements from what in many cases is poorly differentiated material not much more promising than regolith is high, whereas melting dirty snowballs, gassifying the resultant material and separating out the desired elements (heck even go the whole way and perform isotope separation) would be much easier. Robert Forward pointed out that a 1000m diameter comet core weighing a billion tons will yield 1 whole ton of uranium (given its currently accepted cometary abundance of 1 part per billion). Admittedly some S-type and M-type asteroids would be gold mines (literally in the case of a type S rich in platinum group metals) but many/most will be undifferentiated gravel.

The other reason I like comets is they surely would be easily converted to starships – provided the body’s orbit was favourable. I always thought Zubrin’s Nuclear Salt Water Rocket was a good match for a cometary starship. Using the model proposed in his JBIS paper (Journal of the British Interplanetary Society 44: 371–376) the required 10,000 tones of Uranium 235 could be extracted from a 15km diameter cometary nucleus to propel a 1,ooo person, 15 to 10kT payload ship at 3.6%c (with all the reaction mass coming from the comet’s volatiles). Mass ratio would be heavy – but it would be doable. As for deceleration – magsails mostly.

Now we just have to figure out how to keep a complex onboard ecology going……

“Space Settlements: A Design Study” NASA SP-413 (1977) offers all that is needed to house human beings in outer space permanently. Why reinvent the wheel spending vast energies when the basic design is already here, subject to alterations re recently acquired knowledge with the International Space Station. Collecting small asteroids would be useful for amassing the wheel’s rocky radiation shield.

A Chinese landing on the Moon should light a fire under our politicians.

Time is working in our favor.

“…inflated…”

I’m not sure if this is what you mean, but it set my imagination going.

Land a machine onto an asteroid (parked around earth for convenience perhaps?) which makes a hollow beneath it, say 2-3 feet wide and 10-20 feet deep. Put a Bigelow-like inflatable module in its packed up cylindrical form at the bottom of the hole. Pump in gas (or perhaps liquid water at first) to expand it to a sphere or cylinder. The gravel-like substance of the asteroid rearranges itself around the new inclusion.

Repeat many times with similar modules all close to each other. Find some way of connecting the modules up, ideally subsurface, into a habitat. Cover the surface of the asteroid with some sort of netting. Spin the asteroid to create required downward force; the netting keeps the whole assembly together.

You then have a connected set of inflated modules, spinning to create some fake gravity. The coating of asteroid rubble would provide protection from micrometerites and radiation, and also provide thermal insulation and thermal inertia. Also building material.

I suppose in principle you could keep on going until you essentially have a contiguous aggregate of inflatables, with a minimal rubble infill between them and the minimal necessary thickness of rubble surrounding them, thus making good use of the mass of the asteroid for shielding.

Just a thought.

[misquoted — should have read “inflating” — apologies]

Macrolife. Birds build nests and beavers build dams. Maybe we could consider space habitats as being part of homo sapiens’ extended phenotype (the way Dawkins described it). Working up the Kardashev scale, this argument goes to a place that gives me vertigo.

I like that they are looking at asteroids. I’m always hoping to see planetary chauvinism wane.

However one of my pet peeves is 3-D printers as a panacea.

Would sort of feed stock will the 3-D printer have? Regolith of various consistencies from big rocks to silt? What sort of output would the printer have? A rather lumpy inconsistent ceramic is one of the best case scenarios.

Unlesss there are pure feed stocks of various materials. To get that from in situ resources they would need mining infrastructure. To get said infrastructure takes massive equipment.

And what would the printed structure be embedded in? Most asteroids are gravel piles.

It seems to me this seed ship is very optimistic.

Fine powder is a great feedstock for 3d-printing (e.g. “laser sintering”) and other part forming methods. By sintering, you can make high quality ceramic and metal parts. Better than their conventional counterparts. Look up “powder metallurgy” for metals, and in your kitchen cabinet for ceramics.

Fine powder is fairly easy to make using a ball mill, and raw regolith could be quite a satisfactory source of material for ceramics, even without refinement. See for example “basalt fiber” and here: http://www.uapress.arizona.edu/onlinebks/ResourcesNearEarthSpace/resources13.pdf

The pdf you point to talks about making bricks with lunar regolith. And they didn’t sound super optimistic about even making bricks, they talked about the need to have the regolith mixed with a liquid to make piping and moving of the regolith easier. Material strength was hard to achieve.

And these are just bricks. The 3D components envisioned by Made In Space are far more sophisticated.

For reference here’s the Made In Space artist’s conception: https://medium.com/made-in-space/how-we-want-to-turn-asteroids-into-spacecraft-e95d3214d787#.m6oajjiut

The Power and Energy Storage component contains “3D printed in-situ springs and fly wheels… ” Springs made out of ceramics?

How about the mass drivers, are they all ceramic? Seems to me you would need magnets and conducting wire.

And where’s the power source? I’m reminded of Ignatiev’s scheme where his carts are rolling 3-D printers depositing layers of aluminum, iron and silica on the lunar surface to make lunar solar panels from in-situ resources. But most writers singing the praises of Ignatiev’s plan don’t mention where the carts would get the aluminum, silicon and iron feed stocks.

“Fine powder is fairly easy to make using a ball mill,” I don’t see a mortar and pestle included in the Made In Space illustration. What is the volume and mass of this crusher component? The copper mine I worked in as a young man had a crusher. It relied heavily on gravity. As did the shovels, trucks and conveyors that extracted and delivered the material to be crushed.

As I mentioned, asteroids are the way to go (in my opinion) and there are ways to process and exploit in-situ resources. But the Made In Space scheme seems way over-simplified and optimistic.

Laser sintering makes very high quality parts from both metal and ceramics powder. Powder sintered metal parts can be of higher quality than those made in any other way. There are many commercial machines in existence. See, for example, here: http://proto3000.com/selective-laser-sintering-sls-rapid-prototyping-solutions.php

A low-gravity ball mill would not be difficult to design, since a ball mill is a rotating drum, anyway, you can easily find a way for centrifugal force to be used instead of gravity. I would wager that finely ground raw regolith would make fine ceramic parts for all kinds of purposes. Add a magnetic separation process after milling, and you can make metal parts from the nickel and iron in your (asteroidal) regolith.

I don’t know much about Made in Space, but it sounds like they are doing the right thing. Perhaps they are hyping it too much, which causes your annoyance. Unfortunately, that is often necessary if you want to raise money.

I always liked the idea of using hollowed out asteroids as spacecraft. The image of a natural, cratered asteroid being hollowed out, equipped with engines, and sent adventuring is quite picturesque. I still remember David A. Hardy’s painting of an asteroid ark (you can find it in the “space debris” gallery of Hardy’s site).

Unfortunately, I don’t think it is that practical. All that extra weight of rock and metal will make every maneuver much more costly of energy, and natural weaknesses in the rock could imperil the whole effort. As I understand it, many asteroids are little more than flying rubble piles loosely held together by gravity, so finding a suitable asteroid to convert would be difficult.

There are some advantages to such an arrangement, however. All that rock would provide plenty of natural shielding, and the asteroid’s mass would provide plenty of natural resources. You could use your rock’s own mass as remass for maneuvering. A mass driver would be a natural choice of engine for a mobile asteroid habitat, as it could use random rock and slag as propellant.

The asteroid spaceship idea was recently used in Mary Doria Russell’s The Sparrow, in which the expedition to Rakhat (a fictional planet of Alpha Centauri) travel in a constant-acceleration spaceship made out of a converted asteroid. The engines are fed with the asteroid’s own mass. While this idea could work, I suspect it can get nowhere near the relativistic speeds portrayed in the novel. More reasonably, some have suggested using an asteroid spaceship as a generation starship. I suspect any real converted asteroid spaceship would travel quite slowly, so endurance rather than speed would be its main advantage!

Paul forget to mention one important detail of Dandridge Cole’s schemes. Cole did not propose to hollow out an asteroid by simple mechanical means and inhabit the remaining natural shell. Instead, he proposed melting the asteroid and forming it into a space habitat’s hull.

He proposed an ingenious though finicky plan to create this habitat. The space construction crew would first drill a hole straight through the asteroid. Thy would then fill this tunnel full of volatiles and cap both ends. Using a gigantic space mirror, the construction crew would heat the asteroid evenly to red-hot, so that the structure of the asteroid became plastic and semi-molten. At the right moment, the heat would penetrate to the volatiles and boil them. If all went right, the molten asteroid would blow up much like a balloon and become a thin, homogeneous shell around the newly created void. After letting it cool, the construction crew would install the habitable interior landscape and move in.

At least, this was the theory. Whether we could actually pull it off is another question entirely. It is an ingenious idea, but it does lack the romance of converting a natural, cratered asteroid into a mobile starship!

I loved “The Sparrow,” but I was bothered that the starship had this amazingly efficient propulsion system while the lander could make only a couple hops on a full tank of gas (a crucial limitation that was not effectively conveyed to the entire crew). I realize that you probably couldn’t use anything like the starship drive on the lander, but if you can build a ship that can maintain 1 g acceleration/deceleration to Alpha Centauri and back, I’d expect a better lander.

Beat me to the inflation explanation. One additional detail, during the heating and expansion phase the asteroid would be rotated at a carefully calculated rate.

Roger MacBride Allen incorporated a space habitat built in exactly this manner, orbiting an inhabited Earth like world, into his 1985 novel The Torch Of Honor. In the novel he gave a fairly detailed description of how it was built. The habitat had a central role in the novel and the method of its construction played a key part in the story.

Hollow asteroid habitats also features in Greg Bear’s ‘EON’, and Kim Stanley Robinson’s ‘2312’…actually it’s pretty common. Arthur Clarke’s 1953 story ‘Jupiter Five’ employs this trope.

What the article does not mention is how Cole envisaged the asteroid becoming hollowed out. He proposed to start with an asteroid 1-2 miles in diameter, spin it, and put a bunch of concentration mirrors around it and bath it in intense sunlight, until it melts. Once it starts to, melt huge bags of water planted in the center of it would blow up, eventually producing the hollow interior. And then a hollow asteroid 10-20 miles in diameter.

Closer to home, people have built cities carved out of mountains.

Mountains here on earth are generally surrounded by an atmosphere.

A friend of mine wants to homestead the Moon and finance it with a reality show and merchandising. He wants to land settlers near a crater wall, have them blast out a tunnel, install an air lock at the mouth of this tunnel and then pressurize. Voila! Instant living space!

I asked him how do we know the tunnel would be air tight? The crater walls contain fractures and volumes of loosely packed regolith. He replied “We don’t! That adds to the drama and would boost the ratings of the reality show.”

I can see bring something like Bigelow habs near an asteroid. And adding asteroidal regolith to the hab walls for radiation shielding. And if the asteroid has hydrated clays, there may be some in situ oxygen that could help pressurize the hab. But hollowing out an asteroid and living inside? Not practical for a number of reasons already mentioned by other commenters. It’s one of those great ideas from 1970s science fiction that’s really not practical.

Yes, there are so many possibilities. I assume most here have read or seen The Martian. That mindset is what we need. Last time I watched the movie I wondered what Mars would be like some 100 years after the first landings. I envisioned something like pressurized high speed rail crisscrossing the surface between vast settlement complexes. Much of them underground. The Hab would be a museum engulfed by a city. Similar civilizations on Earths moon and others. Automated machines might even excavate and build vast pressurized spaces before the first settlers arrive.

My dad always told me the history of aviation was the history of the engine. That’s true for space too. A robust engine with two orders of magnitude better ISP might get people to the moon in hours and Mars in days at nominal cost. We know how to do most everything else.

I suspect as choice asteroids are converted to large, habitable, comfortable spaces, their orbits will matter less. Instead of colonists trying to expend the energy to change orbit, ships will spend their own energy, to come visit.

The process will more than likely look like this with the asteriod been dismantled.

http://www.space.com/images/i/000/025/341/original/deep-space-industries-wheel-habitat.jpg?1374536710

https://deepspaceindustries.com/

Just so. Like DSI I see a spin hab near the asteroid. I have the spin hab coming out of the rock’s north pole and sharing the rock’s spin axis. Which wouldn’t be feasible if the rock is tumbling, so DSI’s illustration is perhaps more plausible. Here’s some of my sketches:

http://clowder.net/hop/railroad/Cheng.jpeg

I also imagine mirrors to concentrate sunlight if the rock is a good distance from the sun:

http://clowder.net/hop/railroad/Cheng1.gif

Both illustrations come from http://clowder.net/hop/railroad/ChengHo.html

On this theme, there is also Heart of the Comet

An alternative is the concept of “gravity balloons, where the mass of the asteroid provides counterpressure, radiation shielding and physical protection for thin balloons inflated within natural or artificial voids inside.

The colonists are living in smaller structures suspended inside the balloon and rotating to create artificial “gravity”, but can move around in free fall between the structures. For more on this concept see: http://gravitationalballoon.blogspot.ca/2013/03/introduction-to-gravity-balloon.html

The idea of not spinning the outer mass has been around at least since the Stanford Torus design for a space colony. It makes lots of sense. How the habitable volume is constructed has many interesting options. No doubt a few will be tried eventually if humans live in space. The more interesting issues are how to do manufacturing and construction in space, now that the basic structural approaches have been sketched out.

As a major step towards space colonization we have: http://www.universetoday.com/129458/first-3d-tools-printed-aboard-space-station/.

With the ability to print not only tools, but personal and luxury goods, spending time in a small space will become less of a chore. It also means for long trips there will be less need for replacement part, hence less weight for a faster trip.

If our technology advances enough then asteroids can become a nice place to live, which as the population grows will consume the asteroid resulting in populations that can reach tens, or even hundreds, of billions. Such industrial centers would be the place where we could build our first interstellar vessels, or perhaps the final habitat for those billions will itself be in the form of a vessel.

3D printing has become the magic pixie dust whose title has been taken from “nanotechnology”. It is a useful technology, and no doubt will continue to flower. But let’s not make it become the “handwavium” to allow ignoring of true difficulties.

The transhumanists think that genetic engineering will solve most of the problems of humans living in space too. In te long term it will have a role to play, I’m sure.

In the short term, the more likely solution is advanced AI, obviating the need for humans to adapt to space at all. This is unpalatable to most of us space cadets.

3d printing has it’s limits but it is really easy to create raw material for them.

I like the idea of layer system that we can use on the asteroid. Probably the initial settlement would be inside but after you gather enough raw material, you can start creating shells on the outside and start consuming the asteroid under the shell.