With manned missions to Mars in our thinking, both in government space agencies and the commercial sector, the challenge of providing adequate life support emerges as a key factor. We’re talking about a mission lasting about two years, as opposed to the relatively swift Apollo missions to the Moon (about two weeks). Discussing the matter in a new essay, Brian McConnell extends that to 800 days — after all, we need a margin in reserve.

Figure 5 kilograms per day per person for water, oxygen and food, assuming a crew of six. What you wind up with is 24,000 kilograms just for consumables. In terms of mass, we’re in the range of the International Space Station because of our need to keep these astronauts alive. McConnell, a software/electrical engineer based in San Francisco, has been working with Alex Tolley on the question of how we could turn most of these consumables into propellant. The idea is to deploy electric engines that use reclaimed water and waste gases to do the job.

With a nod to the transportation technologies that opened the American West, McConnell and Tolley have dubbed the idea a ‘Spacecoach.’ Centauri Dreams readers will remember Tolley’s Spaceward Ho! and McConnell’s A Stagecoach to the Stars, and the duo have also produced a book on the matter for Springer called A Design for a Reusable Water-Based Spacecraft Known as the Spacecoach. The new essay is a welcome addition to the literature on what appears to be a practical concept.

What fascinates me about the Spacecoach is that it enables us to begin building a space infrastructure that can extend past Mars to include the main asteroid belt. Using electric propulsion driven by a solar photovoltaic array, it achieves higher exhaust velocity than chemical rockets by a factor or ten, pulling much greater delta v from the same amount of propellant. Use water as propellant and you reduce the mass of the system by what McConnell estimates to be a factor of between 10 and 20. Huge reductions in cost follow.

Water as propellant? McConnell comments:

Electric propulsion is not a new technology, and has been used on many unmanned spacecraft. The idea is to use an external power source, typically a solar photovoltaic array, to drive an engine that uses an electrical or magnetic field to heat and accelerate a gas stream to great speed (tens of kilometers per second). Because these engines can achieve much higher exhaust velocity than chemical rockets, 10x or better, they can achieve greater change of velocity (delta v) using the same amount of propellant. This means they can venture to more ambitious destinations, carry more payload, or a combination of both. It also turns out these engines can also use a wide range of materials for propellant, including water.

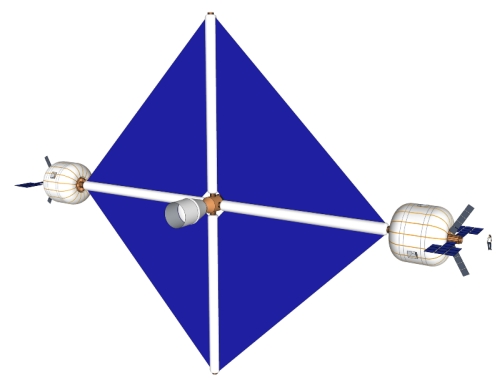

Image: Rendering of the “kite” design pattern for a Spacecoach, with a person shown to the right for scale. This is but one possible configuration, but McConnell notes that the pattern minimizes the materials required even as it provides a sizeable habitable area. Credit: Rudiger Klaen.

We can imagine such ships as interplanetary vessels that never enter an atmosphere. They’re also completely reusable, allowing costs to be amortized, and their habitable areas are large inflatable structures that can be assembled in space. Thus we travel within a modular spacecraft using external landers and whatever other modules are required by the mission at hand. They’re also, compared to today’s chemical rocket payloads, a good deal safer:

The use of water and waste gases as propellant, besides reducing the mass of the system by a factor of ten or more, has enormous safety implications. 90% oxygen by mass, water can be used to generate oxygen via electrolysis, a simple process. By weight, it is comparable to lead as a radiation shielding material, so simply by placing water reservoirs around crew rest areas, the ship can reduce the crew’s radiation exposure several fold over the course of a mission. It is an excellent heat sink and can be used to regulate the temperature of the ship environment. The abundance of water also allows the life support system to be based on a one-pass or open loop design. Open loop systems will be much more reliable and basically maintenance free compared to a closed loop system such as what is used on the ISS. The abundance of water will also make the ships much more comfortable on a long journey.

Having just watched “To the Ends of the Earth,” a superb BBC story about a ship making a passage from Britain to Australia in the age of sail, the word ‘comfortable’ catches my eye. A Spacecoach is a large craft with huge solar arrays and the capability of being spun to generate artificial gravity, thus alleviating another major health hazard. Conditions are more Earth-like, and the abundance of water makes for what would otherwise seem absurd scenarios. Imagine taking a shower on a flight to Mars! The Spacecoach’s water management makes it possible.

McConnell believes that much of the mission architecture can be validated on Earth without the need to build a full-scale spacecraft, with the major emphasis on tuning up the electric propulsion technology that drives the concept. Using water, carbon dioxide and waste gases to test the engines can be the subject of an engineering competition, after which the engines could be tested in small satellites. Ultimately, manned Spacecoaches could be tested in cislunar space before their eventual deployment deeper into the Solar System.

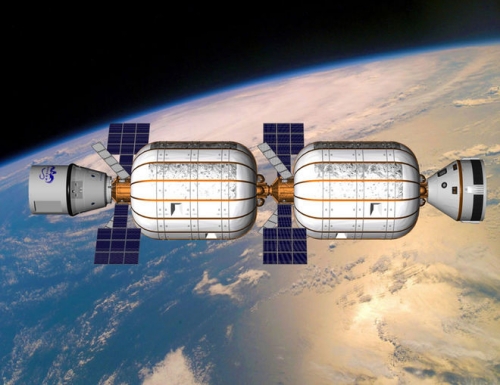

Image: An artist’s concept of two Bigelow BA 330 inflatable modules configured into a space station. Modules like these could provide habitable areas for a Spacecoach. Credit: Bigelow Aerospace (http://www.bigelowaerospace.com).

McConnell calls the Spacecoach the basis of a ‘real world Starfleet,’ and adds this:

These ships will not be destination specific. They will be able to travel to destinations throughout the inner solar system, including cislunar space, Venus, Mars and with a large enough solar photovoltaic sail, to the Asteroid Belt and the dwarf planets Ceres and Vesta. They’ll be more like the Clipper ships of the past than the throwaway rocket + capsule design pattern we’ve all grown up with, and their component technologies can be upgraded with each outbound flight.

So if you haven’t acquainted yourself with McConnell and Tolley’s earlier work on the Spacecoach in these pages, have a look at Traveling to Mars? Just Add Water!, which recaps the basics of the design and outlines surface exploration strategies from orbiting Spacecoaches by telepresence. The key, though, is to mitigate the propellant issue by making consumables into propellant. Get that right and much else will follow, including the prospect of reliable, safe interplanetary transport of the kind needed to build a truly space-going civilization.

And after that? I’ve always believed that after sending instrumented interstellar probes, we’ll expand into regions outside our Solar System slowly, building space habitats as we go, mining local objects for needed materials. A functioning, space-going civilization builds out that infrastructure from within. It’s the ‘slow boat to Centauri’ scenario — our machines, enabled by artificial intelligence, get there first — but it’s a deep future that includes a human presence around other stars. When I see something as evidently practical as the Spacecoach, I get a renewed jolt of confidence that we at least know how to begin such a journey.

Exciting stuff. I have to wonder about maneuverability and resilience. If they detect an approaching rock how quickly can they duck? If the big solar panel gets hit how repairable is it out there? No doubt they’ve figured out how to survive solar flairs. It would appear the kite design works best traveling away from the sun unless it collects power on both sides, in which case it just needs to avoid long periods traveling radially to the sun. To do that they’d have to tack I guess.

I think it deserves a better name than Spacecoach.

It is a fine name. I think they put some thought into it.

Should any Mars long term excursion be planned, a fleet of space coaches could deliver supplies brought up from the earth. It probably would not take a large crew for each ship and with several ships on staggered times the loss of one ship in route would not doom the Mars expedition. It seem quite possible to drop off a Mars to orbit rocket to rotate planet based staff back to Earth. Someday this might become known as a milk run.

I am finding that using H2O2 attacks the hemp fibre string that I used weakening the whole ice structure. I don’t think leaving out the H2O2 will have a huge impact on the mission, it may be better stored in another water/ice tank for sterilisation purposes and used as and when.

Basically what happens if you peroxide or bleach natural fibres to remove stains when washing. High test peroxide (T-Stoff) was used in the Messerschmidt Me 163 Comet rocket interceptor at the end of WWII. A ruptured tank filling the cockpit on a bad landing “dissolved” one pilot.

It has a Victorian/steampunk feel to it. Suggests design ideas!

Humans being an essential “machine” in this scenario, used at least to some extent to translate foodstuffs into fuel, what happens if one ore more humans become ill, or even die? It’s well within the possibilities given the length of the trip.

We’re mostly water, which can be extracted for spacecraft fuel without much trouble.

Thanks, Ron, and I should have been clearer; as I understand the concept, the humans are a sort of on-going machine translating foodstuffs into water/waste, a stream that would be proportional reduced with the loss of a crew member.

Where does that figure of 5 kg per day of consumables come from? That seems far too great. In the relaxed conditions of weightlessness, I doubt that a human needs more than a few hundred grams of solid food (dried) per day, and the verdict of the internet is that he needs about 600 grams of oxygen. How much water? I should think that a liter and a half would be adequate. So it appears to me that 2.5 kg per day would be sufficient?

Second, how do you propose to separate the CO2 resulting from human metabolism out from the exhaled air? With zeolite? How much zeolite will be needed? I suppose the process is not 100% efficient at reusing the zeolite.

The idea appears to be, to use the waste products of human metabolism as reaction mass. But will they be suitable? Basically we are talking about water, CO2, and miscellaneous solids.

Why shouldn’t the water be reused for drinking, anyway? That seems pretty simple, and would solve about half the problem right away.

5 kg H2O/dy is Nasa’s budget. It includes drinking and limited washing. (No-one wants to go to Mars without bathing for months!)

CO2 is currently chemically scrubbed. That is still the simplest solution.

Water is by far the largest waste stream. This is why water recycling is the main target by Nasa. Currently, the ISS urine recycler is about 85% effective when it hasn’t broken down.With abundant water, recycling can be reduced to a single pass of consumption, purified where necessary, and fed to the engines.

With larger crews and engines with higher Isps, recycling becomes necessary. However with the crews and engines that seem feasible, recycling is not needed, simplifying the system and reducing equipment mass.

The whole point is to reach a certain delta-V for a particular mission, it favors to use ion engine. Since ion engine can use a much wider variety of substances as propellant, why not use water, etc?

Also, during space travel, especially long term one, we don’t want to keep astronauts barely alive, we want them to live a relatively normal life under a reasonably comfortable condition.

IF we are talking about using water as radiation shielding in an inflatable habitat , then this inflatable structure most have a double wall with the water being between the two layers of material . If the external layer can be made selectivly transparent to a fitting wavelength of light , this opens up the possiblity of using photosyntesis to regenerate the oxygen . Even more temptating is the idea of developing of microorganism taylored to absorb a much broader spectrum of radiation , including some of the most dangeruos kinds , while using some of the energy gained from photosyntesis to continually repair itself …..another question is if these algae indirectly would form part og the diet …perhaps as food for fish

This idea would fit a relatively fast rotating habitat , where the water would experience a cycle of minor controlled temperature changes .

In some nuclear reactors algae have adapted to growing in the cooling water , so if this can happen by evolutionary accident , the sky is the limit !

Cordwainer Smith had oysters in his sail ships to protect the crew from radiation. A new alga Coccomyxa actinabiotis looks like it might be useful.

The hull was projected to allow some freezing to protect from micrometeoroid damage and provide rigidity for structural support, especially with artificial g, as well as remain liquid. How best to meet the various requirements might best be solved with a design competition.

Before you can have a design competition , you need to have a ‘brainstorming ‘ competition where different ideas are ‘tried on for size’ and developed as far as possible inside our heads

Could you flesh that out a little, including the process? Thanks.

A design contest demands the possibility of advancing the different designs far enough to make a judgment about the winner possible . Normaly each team will try to advance a certain design, the basic idea of which which they were ‘given’ from above in the comand structure of their organisaton . This will demand at least some experimentation , and in space this can be VERY expensive . A ” brainstorming” is an earlier stage , a more open ended process where alle the teams are involved in trying to identify the missing pieces of INFORMATION which would enable a certain design to advance toward the design contest stage , or end it in this cycle .

Thanks for the input. So you are suggesting a common brainstorming session to elicit certain new information, and then the separate groups go off to develop their designs to compete?

More or less , the main thing is not to waste efforts developing into great detail a design which could have been eliminated (at the present level of technology) at an earlier stage , and also be sure that all the theoretical possibilities have been considered ….big-time past examples of the opposite process are countless : just consider the giant investments NASA has made over the years trying to create an airbreathing sucsessor to the shuttle , some of these designs were developed to the last detail , even if everyboddy knew they were build on a non-existing motor type.

At present such mistakes are prevented by a complicated system of technology-level-definitions . The system can tell us what NOT to do , but it does not help us identify how to allocate resources in the most cost effective way .

The best algoritm I know in this connection is a general problem-solving stategy : in case of doubt always go for the simplest and cheapest way to get NEW information out of the problem-space

you already have a spacecraft in orbit. Simply load colonists on international space station. Send up a lander and an interplanetary engine and go to Mars. This gods chosen few thinking is pissing tax dollars on religious elitism. You are expendable trash to be deported to mars and there is a seven billion strong pool of you from which you can be selected. Thats how colonization happens. That should be how this gets done.

You’ll be colonist #1. Congratulations.

Eventually we’ll send along colonist #2. We promise.

Colonization using the ISS would have a single point of failure. The Spacecoach is an attempt to design a simple, low cost, maintainable, robust craft that can be reused and replicated, just like the wagons and coaches of the western expansion. With reduced moving parts, radiation protection, and ideally artificial g, the craft would be more suitable for exploration and even colonization than traditional craft that are complex and need highly trained pilots. The nearest example on Earth is the manned drone that is easy to fly, simple to manufacture, and robust. This just might bring flight to the masses, where aircraft didn’t.

The only thing that will bring “flight to the masses” is far cheaper launch costs, which means StarTram at $50/Kg, or Skylon at maybe twice that. Rockets will not bring it.

But nobody seems to want to fund these alternatives to rockets. And thus there will not be “flight for the masses”.

It’s always about the history of the engine! Everything else we know how to do.

I have reached the conclusion that a spaceship is the only long term solution for Mars colonization and of the entire Solar System. If we are to make analogies, if such a spaceship is like a stagecoach, what we are doing now is akin to a catapult. We are throwing people over there, hoping they will not smash when landing. There is no way of changing the direction, stopping while launched or have any true guarantee of reaching the destination.

People often compare space tech to planes, but it’s a defective and harmful analogy. Planes can land at different airports, turn back, even successfully crash land on land and water. There is even the possibility of parachuting to safety. For space that would translate to a true spaceship: self sustained, artificial gravity, enough fuel to move to change course to different destinations.

I am aware that for space physics this requires a huge installation an order of magnitude larger and better than the ISS and also work on immense timescales compared to today’s mission, but what is the alternative? Catapulting people away and hoping they catch roots?

@Siderite the whole point of the spacecoach architecture is to provide something that is much more like a sea faring vessel that allows for much greater operational flexibility (such as to change your orbit, or even return to the point of origin without refueling). As you point out, a conventional rocket is like a catapult.

The benefit of electric propulsion is that it is inherently redundant (many smaller units attached to isolated electric buses), and the ship can be configured so as to allow much greater delta-v than a chemical rocket (and hence greater flexibility in terms of the places it go, return options, and so on).