Since I’ve just finished reading Stephen Baxter and Alastair Reynolds’ The Medusa Chronicles, a great deal of the action of which takes place beneath the upper clouds of Jupiter, I’m finding the Juno mission more than a little fascinating. The novel shows us a Jupiter that is the habitat of a variety of dirigible-like lifeforms, along with the predators that make their life difficult, and a mysterious world far beneath that I won’t spoil for you by describing.

Juno is delving into mysteries of its own. The spacecraft’s first images of Jupiter’s north pole, taken on August 27, mark the first of 36 close passes that will define the mission. As is so often the case with first-time planetary discovery, we are seeing things we didn’t expect. Scott Bolton (SwRI) is Juno principal investigator:

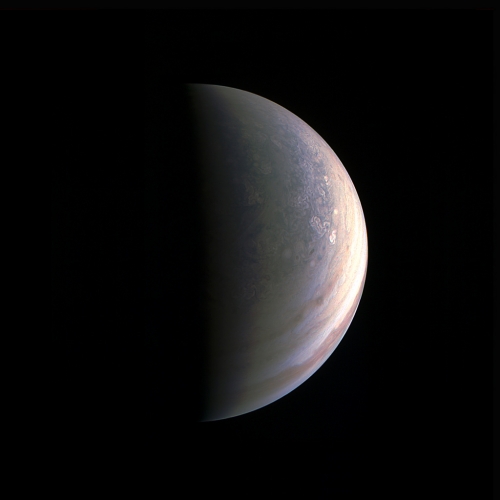

“First glimpse of Jupiter’s north pole, and it looks like nothing we have seen or imagined before. It’s bluer in color up there than other parts of the planet, and there are a lot of storms. There is no sign of the latitudinal bands or zone and belts that we are used to — this image is hardly recognizable as Jupiter. We’re seeing signs that the clouds have shadows, possibly indicating that the clouds are at a higher altitude than other features.”

Image: As NASA’s Juno spacecraft closed in on Jupiter for its Aug. 27, 2016 pass, its view grew sharper and fine details in the north polar region became increasingly visible. The JunoCam instrument obtained this view on August 27, about two hours before closest approach, when the spacecraft was 195,000 kilometers away from the giant planet (i.e., from Jupiter’s center). Unlike the equatorial region’s familiar structure of belts and zones, the poles are mottled with rotating storms of various sizes, similar to giant versions of terrestrial hurricanes. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS.

And we also learn that, unlike Saturn, Jupiter has no hexagon at its north pole. If it had been there, Juno would surely have found it, with all eight of its science instruments collecting data during the flyby, including the Italian Space Agency’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM), which acquired infrared imagery at both north and south polar regions. We learn from the first-ever such imagery of these regions that both poles show warm and hot spots. “JIRAM,” says instrument co-investigator Alberto Adriani (Istituto di Astrofisica e Planetologia Spaziali, Rome), “is getting under Jupiter’s skin…”

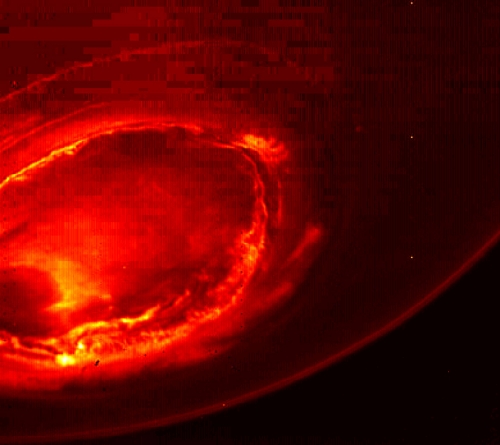

“These first infrared views of Jupiter’s north and south poles are revealing warm and hot spots that have never been seen before. And while we knew that the first ever infrared views of Jupiter’s south pole could reveal the planet’s southern aurora, we were amazed to see it for the first time. No other instruments, both from Earth or space, have been able to see the southern aurora. Now, with JIRAM, we see that it appears to be very bright and well structured. The high level of detail in the images will tell us more about the aurora’s morphology and dynamics.”

Image: This infrared image gives an unprecedented view of the southern aurora of Jupiter, as captured by NASA’s Juno spacecraft on August 27, 2016. The planet’s southern aurora can hardly be seen from Earth due to our home planet’s position in respect to Jupiter’s south pole. Juno’s unique polar orbit provides the first opportunity to observe this region of the gas-giant planet in detail. Juno’s Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) camera acquired the view at wavelengths ranging from 3.3 to 3.6 microns — the wavelengths of light emitted by excited hydrogen ions in the polar regions. The view is a mosaic of three images taken just minutes apart from each other, about four hours after the perijove pass while the spacecraft was moving away from Jupiter. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/ASI/INAF/JIRAM.

Jupiter is capable of violent radio outbursts at frequencies below 40 MHz. I can remember as a boy scanning, with an old Lafayette shortwave receiver, somewhere around 20 MHz, hoping to pick up signs of this activity, which seems to correlate usefully with Io’s position in its orbit. I picked up plenty of noise at various places on the dial, but was too inexpert to know which, if any, could have been signs of Jupiter’s radio storms. Fortunately, Juno has a Radio/Plasma Wave Experiment (Waves), which was able to record the emanations from close by.

The radio activity is coming from the kind of energetic particles that create the gas giant’s aurorae. The Waves experiment should give us a lot more understanding of the phenomenon in coming months. JPL has a video on the auroral activity now available on YouTube. I’ll insert it below, but let me know if this insertion is successful. Recently I’ve heard from a small number of readers that the YouTube material doesn’t display (it seems to work for most, however). I’m still trying to figure out what the glitch is, so if you don’t see it, drop me a note in the comments

No sign of Baxter and Reynolds’ medusae, which are actually Arthur C. Clarke’s medusae, enormous living zeppelins that he described in his 1971 novella “A Meeting with Medusa” (the new novel follows the continuing story of the novella’s protagonist). But then, Juno isn’t exactly designed as an astrobiology experiment. Who knows what exotica it may pass by when it de-orbits and eventually burns up in the dense atmosphere during its 37th orbit…

The video displayed and played back successfully for me and was a joy take in. Jupiter is a gorgeously exotic place.

Indeed!

This sounds exactly like Pink Floyd :-)

It’s great to see these new data from Juno’s first science-oriented perijove especially the images from JunoCam. But it should be remembered that the JunoCam images are not the first good views we have ever gotten of Jupiter’s north pole. Pioneer 11 (whose Imaging Photopolarimeter had an IFOV similar to JunoCam’s) followed a high-inclination trajectory past Jupiter during its historic flyby of Jupiter back in December of 1974 clearly revealing the nature of its polar cloud patterns as they appeared from high above for the first time 42 years ago.

http://www.drewexmachina.com/2016/06/28/our-first-good-look-at-jupiters-north-pole-1974/

Juno is a pivotal mission. Helps constrain the nature of gas giants and can help inform exoplanet discoveries , dovetailing perfectly with Gaia . Between them and the transit spectroscopy coming out of JWST and the ELTs should give us a huge understanding of that planet type compared to just twenty years ago. Also important, but not as obvious is that between them , the critical instruments of JUNO and Europa Multi Flyby provide mission heritage to what becomes a standard gas giant and moons exploration instrument payload . Helpful to further outer solar system missions , massively improved on what went before and not needing extensive and extensive testing. Might help a New Frontiers “Ocean Worlds” bid and any Ice Giants concepts which are surely going to get some priority in the next Decadel. With a suite of ready to use instruments , a new generation of heavy launchers and SEP staging the outer solar system finally beckons . The NASA Outer Planets Advisory Group, OPAG, have been asked to look at concepts up to $2 billion. ( which for remote Neptune/ Uranus is about the equivalent of a $850 million New Frontiers fund elsewhere )

Arthur C. Clarke would revisit the idea of these lifeforms in 1982, in his follow-up to 2001, 2010: Odyssey Two. In it he describes these dirigible-like jovian floaters, and another species of agile winged predators.

Carl Sagan briefly makes a reference to Clarke’s idea in Cosmos too.

When I was a kid the shape of the winged predators evoked in me the appearance of flying manta rays.

Clarke’s Jovian floaters did not have a happy ending in the novel version of 2010 (they received no mention at all in the 1984 film version): They were destroyed utterly when Jupiter was turned into a star.

In the novel, the Monolith ETI determined that the Europan life forms had a better chance of evolving into truly intelligent beings, so they chose them over the floaters. Comforting, ay?

As I have stated elsewhere, Sagan said way back in the 1970s that the Voyager probes would have cameras sufficiently powerful enough to reveal the floaters (beings the size of cities) at least if one were so inclined to search those close up images of Jupiter. The same probably goes for the Galileo images of Jupiter. Once again, since I have never read of anyone on those mission teams having done such a search, perhaps some dedicated “amateurs” might conduct a little local alien search project?

Juno’s images might also work, but I just read that the really close up images from its first closest approach were washed out. I have yet to see any of those images from that part of the flyby so perhaps the rumor has merit?

I can imagine that NASA are not lacking dedicated personnel who would have spotted any granular formation breaking with the uniformity of cloud morphology.

I’m not sure what’s your idea exactly.

My idea is that people should be checking the close up images of the Jupiter clouds for any signs of floaters, which as Sagan said should just be detectable. I was also commenting that I had not heard about any “dedicated personnel” from any Jupiter space mission doing such a project, at least not publicly. Thus my call for dedicated amateurs to pick up the slack.

I’ve just found the sequence in Carl Sagan’s Cosmos where he describes these imaginary jovian creatures.

In my memories the 3d animations weren’t so ellaborate in the 1980s original –I was very little then– I assume that the series must have seen an update sometime after they first aired.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uakLB7Eni2E

Yes, Cosmos was “updated” in 2005, though I cannot fully agree that the new computer graphics either improved the series or were necessary.

Here is a 2013 article from The Planetary Society by the artist who created the original imagery Sagan and Salpeter wrote about in 1976:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2013/20131023-on-hunters-floaters-and-sinkers-from-cosmos.html

And speaking of those Jovian floaters, sinkers, and hunters:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=6308

Sagan had been thinking about Jovian floaters way back in 1966, as shown in the publication of the book Planets, part of the Time-Life Science Library series, of which Sagan was the science consultant. Here is what Sagan envisioned such life forms looked like a decade before writing about the floaters et al:

http://www.projectrho.com/public_html/rocket/images/aliens/zeppelin.jpg

Also found in this section of Winchell Chung’s amazingly detailed site about aliens:

http://www.projectrho.com/public_html/rocket/aliens.php#id–Alien_Lebensraum–Desirable_Real_Estate

Like I said, my memories of the original series are faint, and I never said these 2005 3d graphics were an improvement, you can’t possibly disagree with something I have not said.

Thanks for the links, I had only seen these as a little boy, these images are a great refresher of a warm period of my life.

No, I was not arguing with you here. I was only pointing out that I did not care for the “improvements” done to Cosmos in 2005, nor did I feel they were necessary.

According to Wikipedia, someone did restore the original series in 2009, which hopefully means they put back everything as it was originally intended:

“In a 2009 UK release, Fremantle Media Enterprises digitally restored and remastered the original series as a five-disc DVD set which included bonus science updates.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cosmos:_A_Personal_Voyage

An in-depth review of Episode 2 from The Planetary Society blog:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/casey-dreier/2013/20131021-cosmos-with-cosmos-episode-2-one-voice-in-the-cosmic-fugue.html

The video worked for me, too, with a bit of a wait for the sound at first. Spooky!! I loved it! Thanks!

We live in extremely interesting times. Probes to planets, asteroids and comets. The solar system is now truly our backyard.

Ben Bova wrote about another type of giant life form on Jupiter in his 2001 SF novel titled – shockingly – Jupiter. These creatures are similar to massive whales, intelligent, who communicate with powerful sounds and bioluminescence. They inhabit not the Jovian atmosphere but a presumed layer of water many times the volume of all the waters on Earth.

My questions are, could Jupiter have such a layer of liquid water and is Juno capable of determining its existence? I will save the next obvious questions – could life exist in such an environment and if so what would it be like – once this alien ocean is determined to be either real or otherwise.

http://www.benbova.com/leviathans.htm

I forgot to explain about the link above. Bova wrote a sequel to Jupiter published in 2011 titled Leviathans of Jupiter, which literally delves even further into the details of these creatures along with more descriptions of the alien Jovian environment.

https://www.sfsite.com/07b/lj348.htm

It’s at least not physically impossible that there could be ponds of water floating on top of oceans of methane, with the friction of intense cyclonic activity (of thousands of kilometres per hour) keeping these ponds warm at the quiet centre of the storm.

Oh and what the heck: Remember the bluish colored gas giant exoplanet Polyphemus in the 2009 SF film Avatar? It was literally just a backdrop throughout the story, albeit one that took up a good chunk of the moon’s sky when shown.

Well, apparently Polyphemus has its own version of a floater, though it looks far more like a terrestrial whale than a zeppelin:

http://natehallinanart.deviantart.com/art/Polyphemus-Gas-Giant-Avatar-158453649

Just for good measure, could a world like Pandora exist where its host planet looms so large and therefore so close? The answer is that the moon might exist physically, but anything living on it would be in for a very rough ride:

http://www.thegeektwins.com/2010/07/flawed-science-of-avatar-3-pandora.html#.V9AhLnoTawY

Ljk I don’t know what a layer of water means. Water can only be a vapor in an atmosphere. There are only trace amounts of H20 in the atmosphere of Jupiter. Its atmosphere is mostly composed of Hydrogen and Helium with trace amounts of methane, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide. We learned from Galileo the composition of the atmosphere directly but Juno has three different types of spectrometers which can determine the same thing. Voyager 1 and 2 came up with the same information molecular hydrogen and helium.

You will have to read the Jupiter novels or ask Bova himself. I found an interview with him from 2004 but there wasn’t much detail on the subject:

http://www.astrobio.net/interview/interview-with-ben-bova/

Scientists discover what extraordinary compounds may be hidden inside Uranus and Neptune

Date: September 6, 2016

Source: Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology

Summary:

Scientists have discovered that the depths of Uranus, Neptune and their satellites may contain extraordinary compounds, such as carbonic and orthocarbonic acids. It is no accident researchers have chosen these planets as a subject for their research. These gas giants consist mainly of hydrogen, carbon and oxygen, which are the three cornerstones of organic chemistry.

Full article here:

https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/09/160906103159.htm

The reason there might be not be a hexagon on Jupiter is that Jupiter has a stronger gravity which makes it’s winds blow slower than Saturn’s winds. This is just a educated guess of course.

The Planetary Society just posted some beautiful processed images of Jupiter taken by the Voyager 1 and 2 space probes in 1979 here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2016/0914-a-deep-dive-into-voyager-jupiter.html

The question now is: Where are the Juno close-up images? Especially the ones that were taken closer than any probe before it.

What is the Weather like on Jupiter?

Article Updated: 14 Sep , 2016

by Matt Williams

Welcome to a new series here at Universe Today! In this segment, we will be taking a look at the weather on other planets. First up, we take a look at the “King of Planets” – Jupiter!

One of the most obvious facts about the gas giant Jupiter is its immense size. With a mean radius of 69,911 ± 6 km (43441 mi) and a mass of 1.8986 × 1027 kg, Jupiter is almost 11 times the size of Earth, and just under 318 times Earth’s massive. But this “go big or go home” attitude extends far beyond the planet’s size.

When it comes to weather patterns, Jupiter is also an exercise in extremes. The planet experiences storms that can grow to thousands of kilometers in diameter in the space of a few hours. The planet also experiences windstorms, lightning, and auroras in some areas. In fact, the weather on Jupiter is so extreme that it can be seen from space!

Full article here:

http://www.universetoday.com/15132/weather-on-jupiter/

https://arxiv.org/abs/1610.00250

The effect of Jupiter oscillations on Juno gravity measurements

D. Durante, T. Guillot, L. Iess

(Submitted on 2 Oct 2016)

Seismology represents a unique method to probe the interiors of giant planets. Recently, Saturn’s f-modes have been indirectly observed in its rings, and there is strong evidence for the detection of Jupiter global modes by means of ground-based, spatially-resolved, velocimetry measurements.

We propose to exploit Juno’s extremely accurate radio science data by looking at the gravity perturbations that Jupiter’s acoustic modes would produce. We evaluate the perturbation to Jupiter’s gravitational field using the oscillation spectrum of a polytrope with index 1 and the corresponding radial eigenfunctions.

We show that Juno will be most sensitive to the fundamental mode (n=0), unless its amplitude is smaller than 0.5 cm/s, i.e. 100 times weaker than the n? 4?11 modes detected by spatially-resolved velocimetry. The oscillations yield contributions to Juno’s measured gravitational coefficients similar to or larger than those expected from shallow zonal winds (extending to depths less than 300 km). In the case of a strong f-mode (radial velocity ? 30 cm/s), these contributions would become of the same order as those expected from deep zonal winds (extending to 3000 km), especially on the low degree zonal harmonics, therefore requiring a new approach to the analysis of Juno data.

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

DOI: 10.1016/j.icarus.2016.09.040

Cite as: arXiv:1610.00250 [astro-ph.EP]

(or arXiv:1610.00250v1 [astro-ph.EP] for this version)

Submission history

From: Daniele Durante [view email]

[v1] Sun, 2 Oct 2016 09:28:04 GMT (574kb,D)

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1610.00250v1.pdf

Juno to delay planned burn

Posted By Emily Lakdawalla

2016/10/16 21:28 UTC

The Juno mission posted a status report late Friday afternoon, indicating that they will not perform the originally planned period reduction maneuver during their next perijove (closest approach to Jupiter) on October 19. Here is the bulk of the statement:

Mission managers for NASA’s Juno mission to Jupiter have decided to postpone the upcoming burn of its main rocket motor originally scheduled for Oct. 19. This burn, called the period reduction maneuver (PRM), was to reduce Juno’s orbital period around Jupiter from 53.4 to 14 days. The decision was made in order to further study the performance of a set of valves that are part of the spacecraft’s fuel pressurization system. The period reduction maneuver was the final scheduled burn of Juno’s main engine.

“Telemetry indicates that two helium check valves that play an important role in the firing of the spacecraft’s main engine did not operate as expected during a command sequence that was initiated yesterday,” said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “The valves should have opened in a few seconds, but it took several minutes. We need to better understand this issue before moving forward with a burn of the main engine.”

After consulting with Lockheed Martin Space Systems of Denver and NASA Headquarters, Washington, the project decided to delay the PRM maneuver at least one orbit. The most efficient time to perform such a burn is when the spacecraft is at the part of its orbit which is closest to the planet. The next opportunity for the burn would be during its close flyby of Jupiter on Dec. 11.

Mission designers had originally planned to limit the number of science instruments on during Juno’s Oct. 19 close flyby of Jupiter. Now, with the period reduction maneuver postponed, all of the spacecraft’s science instruments will be gathering data during the upcoming flyby.

“It is important to note that the orbital period does not affect the quality of the science that takes place during one of Juno’s close flybys of Jupiter,” said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “The mission is very flexible that way. The data we collected during our first flyby on August 27th was a revelation, and I fully anticipate a similar result from Juno’s October 19th flyby.”

Full article here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2016/10161412-juno-to-delay-planned-burn.html

To quote:

While it’s true that the mission does have the flexibility to delay this orbit burn without affecting the quality of the science at periapsis or reducing the number of orbits Juno can eventually make, I am sure that the science teams are scrambling this weekend. They didn’t have a plan in place to do science on this orbit periapsis; now they will have to put something together very fast (I imagine it will have many similarities to what they did on perijove 2). And delaying the period reduction maneuver also means a delay in the start of the science mission, and the calendar of future events will be changing a lot. Ground-based observers who planned to observe Jupiter at times corresponding to Juno periapses will have to try to change dates. Among the less important consequences of the calendar change is that all the moon science opportunities that Candy Hansen wrote about in her earlier guest post will now not happen, because any close approaches between Juno and the moons will be on different, as-yet-undetermined dates and different distances. It will take some time to determine when the observation opportunities are with the new orbit, and to plan those observations.

Kind of a mixed bag day for planetary probes:

http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=6653

On the plus side, that means there is a lot of scientific exploration activity going on in our Sol system.

Juno Spacecraft Peers Deep Into Jupiter’s Atmosphere Before Entering Safe Mode

By Paul Scott Anderson

NASA’s Juno spacecraft has been busy orbiting Jupiter and providing fantastic new views of this giant world, something not possible since the previous Galileo mission. While almost flawless so far, the mission has had a few hiccups recently. Juno entered safe mode just shortly before its next close flyby of Jupiter this week, apparently the result of a software performance monitor inducing a reboot of the spacecraft’s onboard computer. The spacecraft is otherwise healthy and Juno is conducting its own software diagnostics to determine the specific cause of the problem. Before this, Juno took its first observations deep into Jupiter’s turbulent atmosphere.

“At the time safe mode was entered, the spacecraft was more than 13 hours from its closest approach to Jupiter,” said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif. “We were still quite a ways from the planet’s more intense radiation belts and magnetic fields. The spacecraft is healthy and we are working our standard recovery procedure.”

The onboard computer rebooted successfully and high-rate data is still being sent back to Earth. Typically, a spacecraft will enter safe mode if its computer detects an anomaly in the general conditions of the spacecraft. It is more of a precaution, so that engineers can assess the problem. Juno turned off its scientific instruments and other non-critical components, but is otherwise healthy with its solar panels still facing the Sun. It is expected that the situation can be remedied soon, as happens in most cases such as this.

Juno first entered safe mode on Tuesday, Oct. 18, at about 10:47 p.m. PDT (Oct. 19 at 1:47 a.m. EDT). The spacecraft conducted its close orbital flyby of Jupiter on Wednesday, Oct. 19, but because it was in safe mode at the time, no science data was collected. The next close flyby is scheduled for Sunday, Dec. 11.

Full article here:

http://www.americaspace.com/?p=95975

To quote:

Despite the glitch, Juno has already been sending back a wealth of information about Jupiter. Most recently, it viewed the planet’s highly active atmosphere by peering beneath the cloud tops with its Microwave Radiometer (MWR) instrument; using its largest antenna, MWR can “see” about 215 to 250 miles (350 to 400 kilometers) below the top cloud deck. The upper atmospheric belts and bands which the planet is famous for are also visible at that depth, it turns out.

“With the MWR data, it is as if we took an onion and began to peel the layers off to see the structure and processes going on below,” said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “We are seeing that those beautiful belts and bands of orange and white we see at Jupiter’s cloud tops extend in some version as far down as our instruments can see, but seem to change with each layer.”

Oct. 25, 2016

NASA’s Juno Mission Exits Safe Mode, Performs Trim Maneuver

Mission Status Report

NASA’s Juno spacecraft at Jupiter has left safe mode and has successfully completed a minor burn of its thruster engines in preparation for its next close flyby of Jupiter.

Mission controllers commanded Juno to exit safe mode Monday, Oct. 24, with confirmation of safe mode exit received on the ground at 10:05 a.m. PDT (1:05 p.m. EDT). The spacecraft entered safe mode on Oct. 18 when a software performance monitor induced a reboot of the spacecraft’s onboard computer. The team is still investigating the cause of the reboot and assessing two main engine check valves.

“Juno exited safe mode as expected, is healthy and is responding to all our commands,” said Rick Nybakken, Juno project manager from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “We anticipate we will be turning on the instruments in early November to get ready for our December flyby.”

In preparation for that close flyby of Jupiter, Juno executed an orbital trim maneuver Tuesday at 11:51 a.m. PDT (2:51 p.m. EDT) using its smaller thrusters. The burn, which lasted just over 31 minutes, changed Juno’s orbital velocity by about 5.8 mph (2.6 meters per second) and consumed about 8 pounds (3.6 kilograms) of propellant. Juno will perform its next science flyby of Jupiter on Dec. 11, with time of closest approach to the gas giant occurring at 9:03 a.m. PDT (12:03 p.m. EDT). The complete suite of Juno’s science instruments, as well as the JunoCam imager, will be collecting data during the upcoming flyby.

“We are all excited and eagerly anticipating this next pass close to Jupiter,” said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “The science collected so far has been truly amazing.” [But what about all those closeup images of the Jovian clouds we were promised? What about the floaters and the hunters and the sinkers?]

Full article here:

http://www.nasa.gov/feature/jpl/nasas-juno-mission-exits-safe-mode-performs-trim-maneuver

Getting what science we can from Juno:

http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/missions/solar-system/first-look-jupiter-through-eyes-juno/

Because the probe may be out of safe mode, but the issues with the engines are not over and are keeping Juno from going into a tighter orbit around the gas giant planet:

https://spaceflightnow.com/2016/10/28/juno-recovers-from-reboot-but-propulsion-problem-lingers/

Maybe next time, floaters (and hunters and sinkers):

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2016/11030800-juno-update.html

To quote:

At the DPS/EPSC meeting last week, principal investigator Scott Bolton spoke about keeping Juno in its long, 53.5-day orbit for a long time, not ruling out the possibility of performing the entire mission in such an orbit. Juno only gets exposed to dangerous radiation when very close to Jupiter, so the spacecraft wouldn’t be exposed to any additional radiation by doing this, though it would seriously prolong the mission.

If the mission has not ended by September 2019, Jupiter will have traveled far enough around the Sun that Juno will pass into Jupiter’s shadow for several hours on every orbit, a condition that it was not designed for and which could harm its power system; the mission would need to develop a solution to that problem.

http://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap161206.html

Aurora over Jupiter’s South Pole from Juno

Image Credit: NASA, JPL-Caltech, SwRI, ASI, INAF, JIRAM

Explanation: Why is there a glowing oval over Jupiter’s South Pole? Aurora. Near the closest part of its first pass near Jupiter in August, NASA’s robotic spacecraft Juno captured this dramatic infrared image of a bright auroral ring. Auroras are caused by high energy particles from the Sun interacting with a planet’s magnetic field, and ovals around magnetic poles are common. Data from Juno are giving preliminary indications that Jupiter’s magnetic field and aurorae are unexpectedly powerful and complex.

Unfortunately, a computer glitch caused Juno to go into safe mode during its last pass near the Jovian giant in October. That glitch has now been resolved, making Juno ready for its next pass over Jupiter’s cloud tops this coming Sunday.

Apparently there is a Juno image of Jupiter’s rings taken from inside the rings which was shown to the AGU crowd, but has yet to be widely distributed:

http://nasawatch.com/archives/2016/12/agu-scientists.html

The Titanic Volcanoes of Jupiter’s Io –Surt Volcano Was 78,000 Gigawatts, Earth’s 1992 Mt Etna, 12 Gigawatts (Sunday’s Feature)

December 18, 2016

The volcanic activity of Jupiter’s moon, Io has been monitored for the last nine years by the Galileo spacecraft and now, with the advent of adaptive optics systems, by Earth-bound astronomers such as those at the Keck 11 Observatory on Maui, Hawaii and the Gemini North Observatory.

“It is clear that this eruption is the most energetic ever seen, both on Io and on Earth,” Franck Marchis and Imke de Pater, professor of astronomy and of earth and planetary science at UC Berkeley. “The Surt eruption appears to cover an area of 1,900 square kilometers, which is larger than the city of Los Angeles and even larger than the entire city of London. The total amount of energy being released by the eruption is amazingly high, with the thermal output from this one eruption almost matching the total amount of energy emitted by all of the rest of Io, other volcanoes included.”

To quote:

http://www.dailygalaxy.com/my_weblog/2016/12/the-titanic-volcanoes-of-jupiters-io-surt-volcano-was-78000-gigawatts-earths-1992-mt-etna-12-gigawat.html

Well I guess we can really forget seeing those floaters unless they are even bigger than already projected:

http://nasawatch.com/archives/2017/02/alternative-fac.html