Larry Klaes has been a part of Centauri Dreams almost since the first post. That takes us back to 2004, and while I didn’t have comments enabled on the site for the first year or so, I remember talking to Larry about my Centauri Dreams book by email. Ever since, this author and freelance journalist with a passion for spaceflight has contributed articles, comments and ideas, as he does again today. Project Orion caught Larry’s attention as a way of using known technologies to enable daring deep space missions. The essay below gives us an overview of Orion and its possibilities, looking at a concept that never flew but still captures the imagination. In addition to his active freelancing, Larry has been editor of SETIQuest magazine and president of the Boston chapter of the National Space Society. He now writes regularly for SpaceFlight Insider, where this article originally appeared.

by Larry Klaes

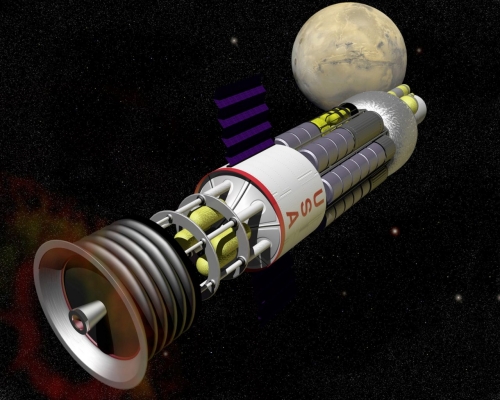

Image: Project Orion concept. Image Credit: Adrian Mann.

At their most fundamental level, all rockets past and present were and are, basically, controlled bombs. Their fuel consists of materials and chemicals which, when activated/combined in the proper sequence and amount, create a series of explosive reactions. The resulting energy release is then directed in a manner so that the resulting exhaust comes out of the end of the rocket away from the payload sitting atop it and the direction that its builders want to send that payload. That is essentially Sir Isaac Newton’s third law of motion put into practice.

When this technological setup works, we have a successful mission. However, when something goes awry, we end up with a vehicle that can go from a powerful and fast means of space transportation to an inadvertently dangerous weapon. As just one large example, if the famous Saturn V rocket – which sent humans to the Moon for Project Apollo between 1968 and 1972 – had ever exploded, the 6.5-million-pound (2,950 metric tons) fully fueled booster would have created a destructive event equivalent to the detonation of a small nuclear bomb, minus the radiation. Thus the reason that no one (excluding the three mission astronauts, of course) was ever allowed within three miles (4.8 kilometers) of the launch pad at Cape Kennedy when a Saturn V was lifting off into space.

Image: Artist’s rendition of NASA’s Project Orion. Credit: NASA.

The former Soviet Union had several real world examples of just such a catastrophe with their equivalent N1 rocket, which they were using to compete with the United States in the race to place a man on the Moon by 1970. Every one of their N1 tests (all unmanned) ended in dramatic failure, with one rocket explosion on the ground practically vaporizing its launch pad and heavily cratering another pad with debris half a mile (almost one kilometer) away.

So now imagine a rocket design where the fuel used were actual bombs detonated on purpose – and nuclear bombs at that. It was known as Project Orion.

Not surprisingly, Orion was born during the Cold War, when the United States and the Soviet Union were squaring off against each other by stockpiling nuclear weapons to let each other know that an attack by one nation using such devices would be fatal for the other, along with most other places on Earth. This concept was called Mutually Assured Destruction, or MAD for short.

In the United States, the power of the atom was also being sold as a way to make life better for everyone. Nuclear power plants were being touted as a cleaner and much more efficient way to generate electricity for our civilization. The binding force of the atom was even seriously considered as a replacement for the fossil fuels powering our land, sea, and air vehicles.

The Ford Motor Company went so far as to come up with a car they called the Ford Nucleon, where a single nuclear fuel rod would keep this automobile of the future operating for over five thousand miles before a new fuel rod was required. The Ford Nucleon never got past the model stages, but the point is that a major American car company took the idea seriously, at least for a while.

Image (click to enlarge). Credit: Rhys Taylor.

If nuclear power could be plausibly applied to mere ground transportation, then using it to send heavy space vessels into the “final frontier” only made even more sense at the dawn of the Space Age. Both superpowers were cranking out those very methods of propulsion at an ever-increasing rate.

In an example of turning swords into plowshares, Project Orion was envisioned as a vessel carrying a supply of hydrogen bombs to be ejected out the stern of the spaceship one at a time. The bomb would then be detonated mere seconds later, where the resulting plasma would encounter a large, thick, shock-absorbing “pusher plate” attached to the end of the spaceship that would simultaneously allow Orion to be moved forward while protecting the ship from the blast and radiation. Each new bomb detonation that followed would push the vessel faster and faster, allowing Orion to reach just about anywhere in the Solar System within one year or the nearest star system, Alpha Centauri, in just over one century under one mission scenario.

Project Orion was worked on under a contract by the United States Air Force (USAF) at the General Atomics company from 1958 to 1965. Project models for Orion soon matched and exceeded the grand space dreams of the era due to its novel method of propulsion.

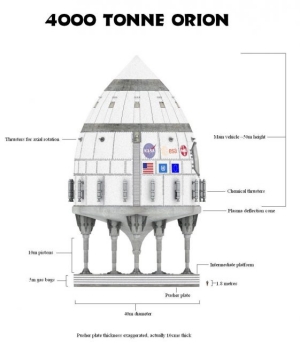

One team member, the famous Freeman J. Dyson of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, envisioned a ship with a total mass of 400,000 metric tons (881,849,049 pounds) of which three-quarters of that weight would consist of 300,000 one-megaton H-bombs weighing 1,000 kilograms (2,205 pounds) each. The rest of the weight would be split between the payload and ship structure and the ablation shield. Detonating the bombs every three seconds (until the supply ran out in ten days under this scenario) would keep the acceleration at a comfortable 1 g, or gravity.

Image (click to enlarge): General Atomics Orion spaceship concept. Credit: William Black.

The plans for Orion were anything but timid. Manned Mars missions using this vessel would have been sent in 1965, followed by a mission to the ringed planet Saturn in 1970! The spaceship in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey, the USS Discovery, was originally designed as an Orion type craft aimed at Saturn in the novel version. The author of the film’s screenplay and novel, Arthur C. Clarke, was also a member of Project Orion. Not only could Orion have conducted a round-trip voyage to Pluto in just one year, but Dyson also calculated a version that could flyby Alpha Centauri in about 130 years at 3% light speed. By comparison, the Voyager space probes will take 77,000 years to reach the distance of our celestial neighbor 4.3 light-years away. The team even considered a massive Orion that could serve as an interstellar ark, which became the vehicle of choice in the 2014 television mini-series Ascension.

As a further reflection of the era, Project Orion was more than just a paper dream. The team built a working 7-foot (2.1-meter) scale model (non-nuclear of course) they called Hot Rod. Launched in 1959 at Point Loma, California, Hot Rod survived five successive explosions that struck its pusher plate and sent the vehicle faster and higher with each detonation. The test vehicle then parachuted safely to the ground, proving that Orion was as least technically feasible. Gulf General Atomic later donated Hot Rod to the Smithsonian in 1972, where it was long on display at the institution’s Air and Space Museum but is currently in storage. However, a scale model of the completed Orion vessel is publicly viewable at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia, in their Rockets and Missiles exhibition. This model was donated to the Smithsonian in 1979 by the General Dynamics Corporation.

Image: Project Orion ‘Hot Rod’ Propulsion Test Vehicle. Credit: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

In the end, Orion was terminated neither by physics nor technology but by politics and a growing public fear of nuclear power. The Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty signed in 1963 forbids testing nuclear devices of any kind everywhere but underground. Two years later, the USAF canceled the project’s budget. Orion became a legendary symbol of an era known for both its far-reaching dreams and excesses of power. To this day, Orion is still the only feasible mean of interstellar travel, both robotic and manned, that could actually be built with current technology and knowledge.

So could (and would) Orion be revived some day? While the United States and Europe (via the European Space Agency) could make the vessel a reality, Orion’s very means of propulsion remain among the major hindrances to such a plan for the foreseeable future. At present, the greatest chance for Orion lies with China. They not only have the means and the resources to undertake such a grand project (as well as vast, remote regions where they could safely test and launch the vessel), but Orion would be a logical extension of their current strivings for major science and technology goals. This author notes that he has no actual knowledge if China has ever conducted or will ever conduct such a project, only that of all the spacefaring nations on Earth, they make for the most realistic choice at present for reviving Orion.

Image: Orion in flight. Credit: William Black.

Russia is another possibility for building Orion on a similar scale as China, but their current geopolitical issues make such prospects questionable on multiple levels. India might also be a contender for their own Orion down the road, but such a future remains to be seen. There are several other nations which have both their own space and nuclear programs, but the thought of them building an Orion in the near future is both questionable and concerning.

As Project Orion has always been about big dreams with even bigger goals, then perhaps we can one day hope that Orion will not only become a method for turning nuclear weapons away from Earth and our species and aim them toward the stars for peaceful purposes, but also that Orion might become a way that we can explore and colonize space together as one humanity.

Image: Project Orion to Mars. Credit: NASA.

For more information on Project Orion, see the following:

Project Orion: The True Story of the Atomic Spaceship, by George Dyson, An Owl Book, Henry Holt and Company, New York, 2003.

These documentary videos on Project Orion here and here, and George Dyson TED Talk here.

For those want even more information about Project Orion and its variants, you must see Atomic Rocket’s pages on it here.

More links to updated information on Project Orion:

http://www.nextbigfuture.com/2016/01/orion-thunderwell-and-nuclear-space.html

http://www.nextbigfuture.com/2014/01/winterberg-reinvents-project-orion.html

http://www.nextbigfuture.com/2009/02/updated-project-orion-nuclear-pulse.html

A Chinese Orion! Wow, that would stir things up…

Stir fry more like it ;)

China has been an empire for over five thousand years. They have gone through multiple periods in history of horrors that would have (and did) destroyed most other empires. Yet now they stand as a major superpower and their ambitions for science and technology are nothing to sneeze at:

http://www.dailygalaxy.com/my_weblog/2016/08/super-babies-to-a-quantum-portal-on-the-universe-chinas-2016-headlines-foreshadow-future-control-of-.html?cid=6a00d8341bf7f753ef01b8d211f917970c

This is not like the Soviet Union during the Cold War, where many of their accomplishments were done for political effect. I often think the West, especially Americans, still have an antiquated view of China, which sadly is not surprising. It is also ironic considering how advanced they were in many ways when Western Europe was still struggling through the Middle Ages by comparison.

http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/watkins/ancientchina.htm

China’s “problem” came in part when they sat on their laurels upon assuming that no other nation was better. They also trashed their fleets which had just performed some major feats of global exploration. However, Europe was becoming hungry and ambitious: They began expanding their exploration, trade and science dramatically, resulting in the world we live in today.

China just recently launched the first quantum communications satellite:

http://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-latest-leap-forward-isnt-just-greatits-quantum-1471269555

If you ignore the hyperbole of the title for this next item, their new space station will be testing directly linking to the human brain:

http://www.dailygalaxy.com/my_weblog/2016/09/chinas-newly-launched-spacelab-empowers-human-braincomputer-interaction-can-transmit-the-astronautst.html

This is why I put China at the top of my list for the nations that could develop Orion. Not because I have any actual knowledge that they will do such a thing, only that they are the most capable. Combine this with their dramatic drive to succeed in so many key areas of science and technology and it may end up being more of a surprise if they do not pursue having their own Orion. If you look at the information I have supplied via links in my article, you will see that pound-for-pound the use of an Orion to help in the development of lunar and interplanetary colonies makes more economic sense than chemical rockets.

What I have seen from China so far leads me to believe that they do have permanent space colonization as their goal. They also know that “owning” the planetoid belt is the key to such a success. They don’t need to send up some battlefleet and declare outright conquest of all those space rocks: They just have to start utilizing them, so in that sense they will own them. There may no doubt be lots of complaining and multiple meetings at the UN for years. Meanwhile China will continue to mine the planetoids and build their space infrastructure while the court battles drag on.

http://www.asteroid.net/the-space-race/chinas-unique-space-ambitions/

They can also develop Orion in space far from any human centers of civilization in a realm where there is already plenty of natural cosmic radiation.

Will the other major spacefaring nations be able to catch up in time? Will they be smart and try to cooperate? Or will private industry swoop in and do the job – and will they want to pursue interstellar exploration, or will they deem it unprofitable?

The United States had these ambitions and abilities decades ago, but we burned our fleet too. It took centuries for China to recover from their error in judgement; will we have that same luxury of time?

While that “burning the fleet” analogy has been used a lot, sadly I think there is a lot of truth in it. The US seems to have stalled in its outward looking stance, even as it demonstrates it technological capabilities. China currently has the resources and political incentives to act boldly. That doesn’t mean that they will act wisely, but they may well be writing the history books. Alternatively, they might just implode or stall out as their economy is almost mercantilist and therefore not sustainable unless they start massive domestic consumption.

China’s Race To Space Domination

To gain an edge here on Earth, China is pushing ahead in space

By Clay Dillow, Jeffrey Lin, and P.W. Singer

Tuesday, September 20, 2016 at 9:23 am

Before this decade is out, humanity will go where it’s never gone before: the far side of the moon. This dark side—forever facing away from us—has long been a mystery. No human-made object has ever touched its surface. The mission will be a marvel of engineering. It will involve a rocket that weighs hundreds of tons (traveling almost 250,000 miles), a robot lander, and an unmanned lunar rover that will use sensors, cameras, and an infrared spectrometer to uncover billion-year-old secrets from the soil. The mission also might scout the moon’s supply of helium-3—a promising material for fusion energy. And the nation planting its starry flag on this historic trip will be the People’s Republic of China.

After years of investment and strategy, China is well on its way to becoming a space superpower—and maybe even a dominant one. The Chang’e 4 lunar mission is just one example of its scope and ambition for turning space into an important civilian and military domain. Now, satellites guide Chinese aircraft, missiles, and drones, while watching over crop yields and foreign military bases. The growing number of missions involving Chinese rockets and taikonauts are a source of immense national pride.

“China sees space capability as an indication of global-leadership status,” says John Logsdon, founder of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University. “It gives China legitimacy in an area that is associated with great power.”

Full article here:

http://www.popsci.com/chinas-race-to-space-domination

For in-depth news on China’s space program, go here:

http://www.go-taikonauts.com/en/

It may “just” be photons, but China and Canada just teleported light particles across an entire city:

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-09-20/teleportation-of-light-particles-across-cities-breakthrough/7853860

China activates its FAST radio telescope, the largest single dish on Earth, on September 25:

http://www.dailygalaxy.com/my_weblog/2016/09/china-flips-on-search-for-alien-life-with-earths-most-powerful-radio-telescope-this-week.html

To quote:

The world’s largest telescope set in the mountainous landscape of southwest China will be completed this week with a huge 1,640 feet (500 meter) wide dish the size of 30 football fields, the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope, or FAST, starts operation September 25. The massive ear will able to detect radio signals — and potentially signs of life — from distant planets.

“FAST’s potential to discover an alien civilization will be five to 10 times that of current equipment, as it can see farther and darker planets,” Peng Bo, director of the NAO Radio Astronomy Technology Laboratory, told Xinhua.

FAST has a field of vision is almost twice as big as the Arecibo telescope in Puerto Rico that has been the world’s biggest single aperture telescope for the past 53 years.

Orion vehicles will violate the test ban treaty as well as the use of nukes in space. Suggesting that China/Russia/India might launch such a vehicle is tantamount to encouraging an abrogation of these treaties.

A consequence of Orion is the building of a rather large number of H-bombs, effectively restarting a national production line. The consequences for nuclear proliferation are frankly horrifying. Russia can barely control the warheads it has that are to be decommissioned. Ramping up production is just asking for trouble. No only would the planet be less safe, but civil liberties would be even further curtailed as national security concerns increased to prevent any attempted use of the bombs for political purposes.

The is no question that Orion’s theoretical performance makes space cadets salivate at the thought of its potential for spaceflight, but Orion should not be

fêted as some forbidden fruit to be tasted if we dare. The ramifications of making Orion craft operational are too grave.

But what you’re saying is not true, this is nothing to do with revamping are cranking up any kind of production lines. What would actually happen, in fact, is that current nuclear devices would be consumed for the fuel that would be used in the mission.

This would actually bring down the number warheads that would be in the arsenals of the world. You shouldn’t be using this as a political forum because you think that this is going to encourage nuclear weapons production. It’s actually quite the opposite

You don’t know that. Furthermore, the production of Orion designed nuclear bomblets will still have to be done. It is possible that existing fissile material, especially plutonium, might be extracted from the nuclear warhead stockpile, but it is also possible that if Orion craft are considered desirable, that new stocks of plutonium will have to be made.

When you have a facility for making bombs, the temptation to use the bombs for other purposes than powering a spacecraft is there. For a government, the Orion bomblets would be a good cover for other more nefarious activities. After all, isn’t this why we have taken so long to allow Iran to make its own nuclear reactor fuels?

True regarding the various treaties. However, the US abrogated the ABM treaty on not nearly so noble grounds as space exploration. If there were a credible commitment by Russia or China (or together) and other countries did not simply wish to inhibit the effort, the treaties could be amended as required.

BTW, Russia has no known issues with controlling its nukes at least in this century. The US has had several famous problems:

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/11/14/us/politics/pentagon-studies-reveal-major-nuclear-problems.html?_r=0

I only mention this to highlight that sometimes we make assumptions based on popular memes that have little basis in reality.

But, to your original point regarding the production of H-bombs on an industrial scale for Orion-type applications, it would truly need to be done under international control with the bombs rendered useless as a weapon by clever design.

I agree that it was more likely a rumor. But can we be sure, especially in the chaos of the break-up of the USSR?

Here are 2 responses on Quora.

“Russia has no known issues with controlling its nukes at least in this century.” This is true. Where is the evidence that “Russia can barely control the warheads it has that are to be decommissioned”?

Oh please. Suggesting that some country might launch an Orion vehicle is in no way ‘tantamount to encouraging the abrogation’ of test ban treaties. Stop trying to gin up a controversy where none exists.

While my language may be a little extreme, I read the relevant paragraph as suggesting that China (and possibly the USSR & India) might have less compunction to follow existing treaties and take that route to dominate space in the future.

I would suggest that we are at the 2 generation remove of events where we don’t recall why we don’t do things that were banned by treaty. We have the examples repeal of the Glass-Steagal Act in banking, of US use of torture in contravention of the Geneva Convention, and a presidential candidate who apparently wants to know why we don’t use our nuclear arsenal, as well as abrogating the afore-mentioned ABM treaty.

At some point our technological capability will be enough for a nation to decide that maybe it is OK to build and launch an Orion type craft. While I hope saner voices prevail, genies cannot be put back in their boxes.

And again I say, this is nothing more than fearmongering for no clear purpose. Wringing your hands and shrieking, “The sky might fall one day!” is frankly silliness.

> Orion vehicles will violate the test ban treaty as well as the use of nukes in space.

China is not a signatory of the 1963 Treaty Banning Nuclear Weapon Tests in the Atmosphere, in Outer Space and Under Water and never ratified the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (which as not entered into force as eight specific states have yet to ratify the treaty). Therefore China would NOT be violating any treaty if it were to operate an Orion-like propulsion system in space.

> Suggesting that China/Russia/India might launch such a vehicle is tantamount to encouraging an abrogation of these treaties.

I doubt that simply SUGGESTING the possibility will have the effect you fear. This bit of hyperbole aside, treaties are abrogated unilaterally or otherwise all the time for a whole range of reasons. These treaties are no different.

China is a signatory to the outer space treaty which bans the use of weapons in space. I have certainly read that this would include detonating nukes in space even for propulsion.

It is a depressing fact that nations will disregard treaties that they deem hinders their ability to gain advantages. The gains are often transient and lead to further complications. the US certainly does not retain te moral high ground in this regard, as one might expect of a hyperpower worrying about its place by the end of the 21st century.

> China is a signatory to the outer space treaty which bans the use of weapons in space.

I didn’t say that China was not a signatory of the the 1996 Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. However, while they SIGNED the treaty, the Chinese government never RATIFIED it and the treaty itself has not entered into force because eight specific states have yet to ratify the treaty. Therefore, if China were to build and operate an Orion-like system, they would not be violating the terms of any enforceable international agreement.

Let’s not talk at cross purposes here. The Outer Space Treaty which does ban the use of weapons in space does include China by accession. This means China has ratified the treaty.

The CNTBT treaty isn’t relevant for the operation of Orion in space, just launch from Earth, which isn’t going to happen.

Certainly China could set up the production of nuclear bomblets on Earth, and then launch them into space. but the country would them have to face the risks and consequences. Will that really be cost free? What path is there for China to successfully skirt treaties to get to fly such a craft?

I have blogged about the idea of using a nuclear grade fissionable material as a shell for Lithuim-7 or DT micro pellets.

NIF out at Livermore have come up short with lasers to ignite DT microcapsules so perhaps this thermonuclear idea might work?

what would be the energetics of such a propellant compared to Orion? What would be the energetics of this propellant compared to Laser Fusion micropellets?

After a long search, I have found old patients that vaguely talk about fissionable shelled fusion micropellets it looks like the applications are as NIF targets.

I have proposed this to NIF and the nuclear stewardship folks, I think these could even be a weapons systems ignited by airborne laser systems but this small mini nuke weapon would violate the nuclear test ban treaty.perhaps we could test them underground? The micropellet pulsed detonation weapon would be our starship fuel

I have a question. The max velocity quoted is .3c, in a flyby (presumably, no deceleration at all) mode. It sounds like this would be based on early 60s bomb designs/ miniaturisation. Does anyone have some idea what top velocity would be achievable with modern bomb designs?

0.03c, that should have read. Typo

Just speculation on my part but a more modern bomb design could simply allow a lighter weight bomb to provide the same yield. This would allow more bombs for a given mass allowing a higher ultimate speed for the craft.

Also, there is a purported possibility of having “shaped” charges that could direct more of the bomb energy in a given direction (e.g. toward the pusher plate) thereby recovering a greater fraction of the energy release.

I will admit I read it a while ago, but my recollection from the “Project Orion” is that there actually are pretty substantial engineering challenges involving the pusher plate and bomb delivery mechanism for an Orion drive revolving around the fact that you need the detonations to occur relatively rapidly (<0.1 sec of each other, I think)

Specifically, I think the Dyson et al. Orion group could never figure out how to 1) physically move the bombs fast enough and safe enough, and 2) actually deliver them to the business end of the pusher plate without leaving a hole in the plate large enough to cause the following bomb (and probably the spacecraft) to be damaged by the preceding explosion. You could imagine some open-and-close gate over the delivery opening, but if that fails (either open or closed) you'd start having some pretty big problems.

Actually, I do remember that book had a pretty entertaining bit where a group from the Orion project went and visited a Coke plant, to see how they move all the glass bottles around without breaking them. I think it turned out that Coke bottle have to move 10x or 100x slower than Orion bombs would, but I always thought that was a nice bit of out-of-the-box thinking.

‘Specifically, I think the Dyson et al. Orion group could never figure out how to 1) physically move the bombs fast enough and safe enough, and 2) actually deliver them to the business end of the pusher plate without leaving a hole in the plate large enough to cause the following bomb (and probably the spacecraft) to be damaged by the preceding explosion.’

If you had multiple mechanisms, interlocked, around the circumference of the pusher plate you could reach quite a high rate of input and protect the remaining devices.

Hi Mike,

Yeah, they thought of that. My memory is that if anything is “poking out” around the sides of the plate, it gets destroyed pretty rapidly.

The explosion is over very quickly, plenty of time to make sure the important bits are not in the way.

How efficient would a typical explosion have been in terms of converting energy released into kinetic energy? In a ball park estimate, how would it compare to a reasonably stretched photon recycling scheme assuming a mirror was always available? Thanks.

Seriously , detonating 300,000 H bombs to go to Alpha Kentauri !

This 20 times more atomic bombs than those which exist today and most of them are just A bombs.

This means an enormous mass of U235 and Tritium ,and an enormous polution to get these masses produced.

And by the way ,as we are currently unable to build such a monster in LEO ,it would have to take off from the surface of the Earth . . . Completely crazy !!!

The legacy of pollution from just the 2 WWII A-bombs is quite serious, let alone the contributions from the Cold War production, and that is ignoring the peacetime nuclear facilities.

Accidental leaks, deliberate sabotage, intercepted shipments, and a whole host of Murphy’s Law problems make this a very unwise technology to pursue. The history of our nuclear arms production should be more than enough to warrant extreme caution.

One could envision production of the nuclear drive devices (see how I did not say”bomb”) on the moon. Such would require a very large industrial base on the lunar surface but, hey, given the technologies and costs of the Orion spaceship, the costs could be an acceptable trade off for minimizing pollution and misdirected use of the devices on Earth. I know, the “Space 1999” scenario looms large…

Just for giggles, the amount of nuclear energy required to kick Luna out and away from Earth (and let us not discuss what it would take to get our moon moving at FTL speeds) would utterly shatter our natural satellite.

Of course the real fantasy was imagining that humanity would have a large manned lunar base by 1999, complete with an apparently endless supply of Eagles.

The pesky science details in fun format are here:

http://catacombs.space1999.net/main/pguide/xrsfb.html

Yes, sadly true. But I still liked the series and remember the characters fondly.

In his autobiography “Disturbing the Universe”, Freeman Dyson says that [because of the health risks from radiation] “The ship was redesigned, so that it would be carried into orbit by one or two of von Braun’s Saturn 5 rockets, and would begin exploding bombs only when it was out of the earth’s atmosphere” (p. 115.)

That was just one of numerous configurations for Orion conceived over the years. Some versions only required a few hundred to less than two thousand bombs, though more would be required if we wanted to reach the nearest stars. The plans went all the way up to an interstellar ark.

As you may have noticed, Orion has never been built and probably won’t be unless it is required to assist Earth against some major cosmic level threat. Apparently the important and noble goal of using former weapons of mass destruction for reaching the stars doesn’t seem to be enough for gathering real support to make Orion happen. As I have said before elsewhere in this blog, it is neither our intellectual nor technological abilities that are keeping us from direct interstellar exploration.

My hope still remains that if we do not come up with another reasonable method of interstellar propulsion relatively soon, that Orion will be seriously considered once again. As others have said elsewhere here, the nuclear technology has only improved since the 1965, including and especially more efficient bombs in smaller packages. Recall that President Obama has also reestablished nuclear weapons testing among other nuclear projects:

http://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/22/us/us-ramping-up-major-renewal-in-nuclear-arms.html?_r=0

Hopefully some new and updated knowledge will come from this to assist in making an even more efficient and safer Orion down the road, though that is not at all what the current Administration has in mind.

Well I find it totally ironic that they are worried about the test ban Treaty. In this context; I mean after all, if there was an asteroid headed toward earth and interception was required ASAP and this was the fastest route to get there, do you think the nations of the earth would say, oh, no! We got a test ban Treaty and we dare not set off nuclear bombs behind a vehicle to rescue Earth.

Politicians and politics can always put aside their scruples when it’s in their best interest to do so, and I’m a cynic when it comes down to these matters, but I do feel that if there is a practical and immediate way to do these interstellar things, then I would suggest that if there is a will and the money to do so we could probably find a way around all these treaties and head on off into deep space. But that’s just me

I think there is a huge difference between using a few nukes for planetary defense when appropriate, and building many bombs for a spaceship trip.

I agree that that’s about the most plausible scenario for reviving Orion in the near future – a large asteroid headed towards Earth which could only be diverted by such a method. However despite movie myths, the largest asteroid that could be headed our way is a bit of 10 km in diameter – that’s clear from the cratering record of the inner solar system from Mars inwards. Many craters of course were made by much larger impactors – but they all date from more than 3 billion years ago. We just don’t get 100 km impactors any more, probably because large comets have to do many flybys of Jupiter to flatten out their orbit to intercept Earth and by then they have broken apart like comet Shoemaker Levy or indeed hit Jupiter again like that comet, or hit the Sun or been ejected from the solar system. And there are no large objects in the asteroid belt that could be perturbed by Jupiter to hit Earth in the near future. Small fraction of a percent chance of Mercury hitting Earth due to resonances with Jupiter, but that’s billions of years into the future and almost certainly won’t happen.

So we are talking about something at most a bit over 10 km in diameter. And we already have mapped all the NEOs of that size, so it can only be a comet – or the much rarer Oort cloud asteroids. And probably already done several flybys of Jupiter to flatten out its orbit but currently still long period. In that scenario we’d probably know about it some years in advance.

This is a very unlikely scenario as it is a 1 in a million chance of being hit by a 10 km asteroid but we have found all the 10 km NEOs already and probably only 1 in 100 impacts are by longer period comets so that makes it a 1 in 100 million probability to happen in the next century.

So could Orion deflect such a comet? It’s a bit hard to get the numbers to work, especially if you only know a year in advance that it is going to impact. Suppose it’s a clone of comet Halley, mass 2.2×10^11 tons and with relative delta v to Earth typical of a comet impact of, say. 40 km / sec. And make it an Orion with mass of 10 million metric tons as for the interstellar starship. Then a kinetic impact a year in advance, hitting it in the opposite direction to its direction of motion towards Earth, and not taking account of any extra delta v from the impactor itself, would deflect it by 40*10^7/(2.2×10^11) km / sec so in a year it would shift it by 365*24*60*60*40*10^7/(2.2×10^11) = 57,000 km. So that is definitely possible. Indeed to deflect by the diameter of the Earth you only need to hit it 12,000*(2.2×10^11)/(24*60*60*40*10^7) days in advance or 76 days in advance. So if we did have a 10 million ton interstellar Orion ready for launch, we could deflect a Halley clone, if we can get it there just two and a half months before impact. There I’m just ignoring the delta v imparted by the nuclear weapons. If we used the faster and smaller “momentum limited Orion” then it would have a delta v of 10,000 km / sec after 10 days accelerating at 1 g, and it would have a mass of 100,000 tons so then you replace that 10^7 by 10^5 and the 40 by 10^4 to get 12,000*(2.2×10^11)/(24*60*60*10^4*10^5) or 30 days before impact – and checking that it would reach the maximum speed before hitting the comet – by s = at^2, then it would travel 0.5*10*(24*60*60)^2/1000 in ten days, so 37 million kilometers, and in 30 days the comet at 40 km / sec would travel 40*24*30*60*60 km or a bit over 100 million kilometers, so it would be far enough away for a momentum limited interstellar Orion to intercept it and deflect it through kinetic impact alone if you launch it one month before impact. You could of course send many tons of nuclear bombs as the payload and explode them on impact, so probably it doesn’t need to be such a large Orion as this to deflect it 30 days in advance.

There I’m just using the figures from the wikipedia page on Orion for a ballpark figure to get the idea – but though wikipedia often has mistakes – they tend to be accurate about things like this I find. Would need to double check with the sources of course.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Orion_(nuclear_propulsion)#Theoretical_applications

The estimated cost of 0.1 year of U.S. GNP seems a figure that in such a scenario we would be able to find with such high stakes.

So, I think that surely it could work but the problem is, that this is such an unlikely scenario. The comet impact this century particularly is so unlikely that on average you have to wait 10 billion years for it to happen. Seems that large comets nearly always get converted into short period comets before impact and we’d have detected those already. A 1 km impactor is more likely – we will map 99% of those by the 2020s but suppose one of the remaining ones is on impact course with us? Then divide all the figures by 1000, we can deflect it with the momentum limited Orion maybe even hours or days before impact. And even more so for the 100 meter ones.

So I think it is clear that the Orion would be a very effective defense against asteroids of all sizes. But the problem is that it would need to be built in advance, and I can’t see us building something like this when it might only be needed several thousand years in the future. Especially with the problems of the test ban treaty – the OST treaty I think is no problem because you only launch it into space when there is imminent danger and it is not actually being used as a weapon of mass destruction. The OST doesn’t prohibit nuclear fission in space, for instance nuclear reactors, Russia has flown several of those, not just RTGs but nuclear fission reactors. I think you could argue that whether it is a weapon of mass destruction depends on its purpose, and especially if it is under control of an international body and only used for planetary defense, I can’t see that being a problem. And again – the test ban treaty would be violated only on launch.

But you’d need to do test launches to make sure it works and that I think is where the problem lies in building this on Earth. That together with the problem that it might not be needed for thousands of years.

And as well as that – well rather than build Orion I think it makes much more sense, for far less outlay of finance, to build space telescopes to detect asteroids well in advance. The B612 Sentinel, cost 0.5 billion dollars, would find most of even the smaller ones down to 20 meters in less than a decade and if we can have a big program of launching space telescopes to detect asteroids and comets, then for much less than the cost of Orion we can predict any impact decades in advance. And – as well as that, they will nearly always do several close flybys of Earth before impact, and those close flybys have “keyholes” only a few hundred meters in diameter, deflect it so it misses the keyhole and it won’t hit Earth. In scenarios like that, then just painting the asteroid or comet white might give enough deflection, or other gentler scenarios.

So – I find it hard to come up with a scenario where we would actually build Orion for asteroid defense, even though it would indeed be a very effective way of deflecting asteroids once built.

There is one way of building it without violating the test ban and testing it also, and that’s to do it on the Moon. They’ve found uranium on the Moon.

http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/badastronomy/2009/06/29/uranium-found-on-the-moon

So I can see a future where they build Orions on the Moon, once there is an established industry there, a few decades into the future, and a more peaceful future where it can be recognized that it is not a weapon of mass destruction by design, instead gets classified as a propulsion system which uses nuclear materials, and there are no worries about terrorists or the like hijacking an Orion and using it to threaten Earth.

It would make more sense to load up the front with deuterium fuel so that when the craft hits the comet/asteroid it will undergo a fusion event. At greater than ~1000km/s fusion becomes available due to impact velocity. I thought about using this technique to remove Venuses atmosphere, it would need a lot though >125 billion tons.

Any powerful enough propulsion system IS a weapon by design. I recall Larry Niven’s Ringworld where the author also makes this statement and even describes an interstellar war where Mankind wins due to the superiority of their (nuclear) interstellar engines, becoming a powerful nuclear lance when pointed toward the enemy.

Even without using nuclear bombs. Let’s think about the gigawatt laser envisioned to accelerate the Starshot probe. Everyone acknowledged that it would be more efficient -both for solar power conversion using giant solar panels and laser power reaching the probe due to the absence of an atmosphere- if it were built in orbit or on the Moon. But should it be built in space and then aimed toward a target on the Earth, it would instantly become too powerful a weapon to be put in one government’s hands, hence the choice to build it on the surface of the Earth. I don’t think that the reason is really that it would be easier to build and operate a dozen of nuclear plants than launching a series of self-deploying solar arrays.

So if we are going to design engines able to bring us to the stars, they are going to have an enormous destruction potential anyway, and they will represent a significant threat if they fall in the wrong hands, no matter how of for which purpose they are initially designed.

So nuclear or not doesn’t really matter, if we are mature and civilised enough as a species to go interstellar, when we have the technology, we won’t use it as a weapon. On the contrary, if we aren’t civilised enough, as soon as we have the technology to reach the stars we will use it as a weapon, and the Fermi paradox will get solved in a sad way.

Not just propulsion systems. As our technologies become more powerful, many can have dual use. More importantly, as the economy grows, these technologies become available to groups and individuals. So far the approach has been control, leading us to a very authoritarian world, which in turn creates push back, making the world a potentially more dangerous place.

Creating distance between populations with space colonization is one way to reduce the existential risk, although this will not help the majority of the population left on Earth. I don’t know what the solution is that allows us to keep our freedoms and furthers development of technologies that can be used as weapons. I certainly hope it isn’t one of the Fermi paradox solutions.

What would be the effect of that much radioactive plasma in space?

Zero as it will be going out the back pretty fast…. unless it enters our magnetic field region and then there is going to be some issues!

Nil. The sun already puts out much more than an Orion craft would.

Actually, a single nuclear blast in the Van Allen radiation belt created persistent adverse effects lasting over one year. The relative primitive electronics of the satellites of the day (1964) were fried and failed (both American and Soviet).

http://www.flybynews.com/cgi-local/newspro/viewnews.cgi?newsid977435363,53228,

“…But another effect became extremely disconcerting. Hunter said that the bomb blast loaded the belts longitudinally in a pie shape from pole to pole. But where the Air Force had expected the radiation from the blast to remain in the belts for only two days, “There was a trapped radiation phenomena” — in other words, the extraordinarily high radiation levels refused to disperse. In fact, Hunter said, the energy from the A-bomb blast stayed in the belts “for over a year, maybe more.” Hannegan said that the trapped radiation knocked out all American and Soviet equipment that passed through it. “The area was militarily neutral,” said Hannegan.”

That phenomenon could be a show stopper for Orion departing from Earth orbit.

Hmmm, build the nuclear drive devices on the moon, assemble Orion at a convenient Lagrange point and then to the outer solar system or that gravitational focal point if not the stars! Needless to say, the amount of space-based infrastructure is far beyond any near-term possibilities.

A physicist acquaintance indicated that the referenced article greatly exaggerated the effect of a nuclear blast on the Van Allen radiation belt. So, it may not be a showstopper but more research is clearly needed in this area if such a propulsion system is to be developed.

Well, there’s one way to find out…

Yet we have a society where 1.1 trillion dollars has so far been spent on a fighter jet, the F-35, and it still isn’t quite ready for combat. Imagine what NASA or another space agency could have done with such funds.

http://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2011/03/the-f-35-a-weapon-that-costs-more-than-australia/72454/

Yes, it is a sad fact that those who rule us have no other ambition than to rule. If this is construed as political, my apologies and please delete.

With modern technology the Orion bomblets could be made much safer by say having the devices detonated by laser control .i.e. the devices are pushed out the back and a number of lasers are fired on surface sensitive devices all at once to cause the denotation. There may be a way to save the pusher plate by having a powerful magnetic field which first deflects ionised products and secondly captures any ionised sputtered material for reuse after cooling.

Laser fusion is the approach the BIS took for their Project Daedalus ship. As Larry’s article was predicated on technologies (and resources) we have today, that is a technology that must be ruled out. The NIF still hasn’t managed to successfully ignite a heavy hydrogen pellet in a way to generate more energy than it requires to ignite, let alone ignite a rapid stream of pellets. BUT when (hopefully not if) they do, it would be a preferable technology, even if the fuel source would need to be extra terrestrial.

The fission component can be quite small compared to the hydrogen fusion component, as for the BIS fusion based design if they tried X ray free electron lasers they may get a lot further.

I’d like to see where Icarus Interstellar ended up regarding fusion for interstellar flight.

If we are being watched, I imagine it would be great entertainment to witness an Orion spaceship deployment. I’ve always thought the Orion concept so ridiculously cartoonish as to be a joke. I would be embarrassed to be associated with it. It is the ultimate Heath Robinson spaceship.

They would be laughing at us.

Fascinating article about one of the forgotten gems of the Space Age’s golden era!

I’m a little confused though…the article states that 1 MT H-bombs will be used, but the detailed figure and diagram discuss the use of 15kt fission bombs. Were there two designs, one for a Mars mission (smaller 15kt fission bombs) and one for the interstellar mission (1MT H-bomb)?

The 15kT fission bomb is about what is required to set off the 1 MT.

I agree with Alex Tolley. It’s just too dangerous of a space vehicle. A study on it mentioned the increased radiation levels on health due to the nuclear fallout and increased cancer death rate. Also there is a electromagnetic pulse that can damage unshielded electronics and radar blackout from the fireball etc.

Orions capabilities are impressive though. I recall reading in Michio Kako’s book .”The Physics of the Impossible,” Orion could have a top speed of ten percent the speed of light and it is a nuclear pulsed rocket with a specific impulse of ten thousand to one million and much larger payload than liquid, propellant conventional rockets. Three percent light speed is still good.

The 300,000 one megaton hydrogen bombs is a lot and I have to think that one must seriously scale up the size of the original Orion rocket in order to have room for the H bombs.

Some important problems in the interstellar design have not been addressed. I always thought it was an atomic bomb which launched Orion from the ground like a yield of only twenty kilotons. What kind of G forces are we going to have with the acceleration of a one megaton H bomb?

Also, the pusher plate must me made much wider for the use of a one megaton hydrogen bomb which will cause a huge fireball due to the ionization of the air by the radiation of the explosion. Some of the hot air of the fireball is much wider than the pusher plate might hit the sides of the rocket? Also the debris and dust will come off the ground at high velocity and might hit the side of the rocket if the Hydrogen explosion is too near the ground. Consequently, it might be a good idea to use a lot of lower yield atomic or H bombs when launching it from the ground. In space there is no air to be ionized with black body radiation or soft x rays and gamma rays at 10 to the 7th F so we won’t have that problem. The one megaton H bombs could be used in space.

Finally the pusher plate has to really be made extra strong. A hydrogen bomb can reach a temperature of ten billion degrees in the dead center. How close are the H bombs explosion to the pusher plate? How are they going to stop the heat from melting it? The pusher plate has to be able to take a lot of punishment from 300,0000 H bombs and still keep on working. I think it can be done but think they have to make the ship bigger and stronger.

Hi Paul & Larry

The Interstellar Orion didn’t use hydrogen bombs as we presently know them. The specific concept Dyson alludes to is a pure deuterium fusion device. He assumed maximum burnup and negligible high-Z elements in the resulting plasma, thus producing an expanding plasma ball with a particle speed of 30,000 km/s. Because the pusher plate is, at most, 50% efficient at momentum transfer, the resulting effective exhaust velocity was 15,000 km/s. By an efficiency argument Dyson determined a mass-ratio of 4 was desirable, so the cruise speed was 10,000 km/s.

There’s no current fusion device design that can get that level of performance. At most a particle velocity of about 3,000 km/s is produced, due to the large high-Z fraction in the plasma. Assuming the same momentum transfer efficiency then 1,500 km/s is a stretch goal for a present day Orion’s exhaust velocity. On par with the maximum for a Dual Stage 4-Grid ion thruster, though much more energetic. A DS4G would take decades to hit top speed, while an Orion would take days.

Would it be possible to improve these numbers by modifying the pusher plate using magnetic induction, making it more of a ‘nozzle’, like in the pulsed-fusion designs?

The bombs would be disk shaped, so when they explode they’d produce two roughly collimated jets of gas oriented along the axis of the disk. One would be directed after, the other would strike the plate.

The source of inefficiency is the gas dissipating energy in this collision. If the gas could be made to rebound elastically this would improve the performance. It would also reduce the heat dissipation in the plate, the reradiation of which is what limits acceleration.

This suggests the pusher should have some sort of magnetic cushion to prevent the plasma from directly hitting the plate.

IIRC, the plan was for the pusher plate to be mildly ablative; They had a test where a large steel ball, (I think) was near one of the atomic bombs, and it survived with surprisingly little damage, evidently due to ablation of grease on it.

For the details on what you are referring to, go to this page and scroll down roughly halfway:

http://www.nextbigfuture.com/2016/01/orion-thunderwell-and-nuclear-space.html

Hi Adam,

(I’m a real fan of Crowlspace, by the way). I was wondering whether you might get better performance using a scaled-up interstellar version of Solem’s Medusa-Orion configuration. Has anyone actually looked at the figures? Admittedly the shroud would have to be pretty resilient (woven defect-free carbon nanotubes or graphene maybe?) to take all that pounding. Would the performance be improved by incorporating superconducting wires into the shroud – effectively making the ship a Medusa – MagOrion hybrid?

Final dumb question (sorry to everyone for being a pest) but in Cosmos Sagan gave a top velocity figure for an interstellar Orion of around 0.1c? How would that be possible – as I understood it the Momentum-limited interstellar Orion had a peak velocity of 0.033c? Are there any studies for that backup the claim?

Hi Phil

There’s no physical need for the mass-ratio to be as low as Dyson describes. His computation was more in terms of fuel efficiency, so if one used stages, the final velocity would be higher. His paper is available on-line for all to read his argument.

As for Sagan, I think he was giving an order-of-magnitude figure, which 0.03 c is compared to 0.1 c.

I’m going to reread Dyson’s book over the next couple of days, but this discussion is making me jump in with off the top of my head recollections . . .

These were bomblets, it was not the equivalent of detonating 300,000 “average” sized hydrogen bombs. They were indeed shaped for maximum propulsion efficiency. It was not to be launched from Earth, only from LEO. Ablation tests demonstrated the feasibility of a pusher plate performing well in the face of the detonations. These were not crazy folks designing and planning this, but some of America’s most well-respected nuclear scientists and bomb experts.

And toward the finale of Dyson’s book, the main designer, a Ph.D. whose name escapes me, states that Orion may return someday when Earth is threatened by an asteroid or comet, because it would be the only technologically feasible way we have to get a spaceship to the target in a really fast timeframe.

This isn’t mad scientist stuff. It’s controlled explosions, simply the release of energy levelled up from chemicals, but well within our ability to control.

Erik Landahl said on September 16, 2016 at 18:12:

“And toward the finale of Dyson’s book, the main designer, a Ph.D. whose name escapes me, states that Orion may return someday when Earth is threatened by an asteroid or comet, because it would be the only technologically feasible way we have to get a spaceship to the target in a really fast timeframe.”

In the 1998 film Deep Impact, an Orion variant they named Messiah is used to try to stop a comet threatening to hit Earth.

Hydrogen bombs can be made more efficient and “lighter” (proportionally less high-Z elements) by making them larger. For bombs > a few GTs, no compression of the fusion fuel would be needed. A sufficiently large bomb would be mostly a tank of liquid deuterium with thin walls.

This suggests the interstellar Orion should be made extremely large. The cost may eventually be dominated by the cost of deuterium, which suggests mining Venus, where the D/H isotope ratio is two orders of magnitude higher than it is on Earth.

Water is present in the atmosphere of Venus at the 50 ppm level, so it’s not a concentrated resource.

Mars is enriched in deuterium compared to Earth, and has concentrated masses of conveniently solid water.

It’s possible that the Moon has captured large amounts of water, as ice, in the various lava-tubes that have been spotted in recent years. Isotopic fractionation would work quite effectively on the Moon’s tenuous vapour veil, so deuterium may well be enriched there too.

I wonder if it would be easy to steer such a craft. You’d have to position your nukes just so, and detonate them at exactly the right time.

There is also the little detail that the Captain of an Orion ship would control a substantial nuclear arsenal. “Small” nuclear bombs are still pretty fearsome weapons, and so you would definitely have to worry about the stability of the crew of an Orion ship, at least until it got well away from Earth.

How about all those captains of submarines carrying nuclear missiles which could sit off a nation’s coast and launch a strike against an enemy in a matter of minutes? They have multiple safeguards put in to ensure no one person goes off the deep end and launches those weapons.

One can assume a good number of safeguards would be in place for Orion’s nuclear payload.

We could just use open plutonium bomblets with an explosive covering. Once ejected behind the pusher plate a laser/electron system causes the explosives to explode simultaneously over the surface causing a very smooth well shaped compression front. No need for electronics and heavy containment materials, a squirt of absorber material just before denotation will absorb a lot of the high energy radiation as well.

Using an atomic salt rocket would have the advantage of no fission bombs but rather a continual controlled fission reaction. Not quite as strong a performer as Orion but still pretty potent. Considering that we had the solid core reactor rockets almost ready to fly in the 1960’s it would seem that the atomic salt rocket would be a reasonable possible advancement. With any fusion or fission there is the problem of radioactive exhaust, which means they could only be used as an upper stage or in LEO. So be it with this design.

https://www.npl.washington.edu/AV/altvw56.html

I like Solem ‘Medusa’ configuration [1] and Dandridge Cole’s Aldebaran[2].

http://www.astronautix.com/a/aldebaran.html

As George Dyson pointed out , in 2002, many Project Orion documents are still classified … maybe we will see them some day?

[1] Solem, J. C. (January 1993). “Medusa: Nuclear explosive propulsion for interplanetary travel”. Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 46 (1): 21–26. Bibcode:1993JBIS…46R..21S. ISSN 0007-084X.

[2] Cole, D. “The Feasibility of propelling Vehicles by Contained Nuclear Explosions,” Advances In the Astronautical Sciences, Vol. 6, pp. 726-742, 1961.

Future citizens of the Solar System, and the colonies of humans living on planets circling distant suns, will undoubtedly look back at discussions of hydrogen-bomb-driven space ships with the same sort of whimsical curiosity that we look back on Da Vinci’s plans for Flying Machines.

We will go to the stars.

We will not be using the technology discussed in this thread.

This idea, like Da Vinci’s ideas about flight, is a non-starter. It’s going nowhere.

We will not be throwing hydrogen bombs out the back door of spaceships to power our way through the cosmos.

That is simply not going to be the way we are going to move forward in space.

Possibly, but all of the other methods for fast interstellar travel – meaning within or about the length of an average human lifetime – have major technical hurdles to overcome. Even controlled and sustained fusion has yet to be obtained even after decades of effort and billions of dollars.

Even the much lauded Breakthrough Starshot has numerous non-trivial issues, including the requirement of a very powerful laser for propulsion which could just as easily be turned into a major weapon as any bomb:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/quora/2016/09/06/one-industry-insider-is-betting-that-breakthrough-starshot-is-completely-unattainable/#6fd87892795b

We also cannot count on the future and its residents to carry on our ideas and hopes. Even if a civilization-level disaster does not befall our descendants, they could turn away from the stars for a number of reasons. Better if we try to make our future now with the tools we have.

I read this as a plea to build Orion, or something like it. Isn’t this by implication asking the builders to ignore the various treaties against using nukes in space?

I have no issues with “nukes in space” if they are being used for non-hostile purposes, which I believe the treaties are only referring to testing nukes for military purposes. Plus as has been said elsewhere, not everyone has signed these treaties.

While I recognize these are not weapons per se, the Soviets put up their share of nuclear-powered spy satellites, a few of which infamously dropped back onto Earth out of control. Why were these not banned as well?

And if humanity and Earth some day find themselves in the kind of trouble that could lead to the extinction of the species – and something like Orion is going to save our skins – then I am sure several loopholes will be found in the process, or perhaps the ban will be temporarily lifted altogether to stop the threat (or get at least some of our species away from Earth, depending on the size of the problem).

I just find it not only disappointing but even rather unrealistic that an Orion style “ark” could be built in time if some disaster were about to befall us. It would make a lot more sense to work on interstellar travel in times of peace and prosperity for the betterment of our species rather than last minute panic and riots due to some impending cosmic doom.

Already recently we have had several planetoids zip past Earth with barely any decent warning time. They were not going to hit our planet and probably would not have done global scale damage, but should we not be ready in advance in case something should be coming our way? If we could not nuke such a threat then at least we might be able to save some of our fellow humans and other terrestrial life forms. Better than sitting around waiting for the end while panic and chaos ensue.

There is a difference between nuclear material in space that cannot go bang and bombs. RTGs are fine. NTRs are fine too, as are nuclear reactors in space, although I am not that sanguine about launching either.

The implication is that it is OK if treaties are broken. rather than continue on that path, we should be reinforcing existing treaties unless they are truly obsolete.

These nuclear-powered satellites couldn’t be used as weapons.

Banning nuclear weapons in space was, and remains, important as a nuclear weapon in space can be deorbited and reach its target in less time than an ICBM, or IRBM from a submarine. The world is not safe with nuclear Damocles swords held over our heads.

Nuclear power in space is a very different proposition. No one expects a nuclear power plant to explode because they are not designed to do so. But if a power plant worked by exploding nuclear material in a relatively uncontrolled way, that would be a very different proposition. (IIRC, there was a suggestion to explode H-bombs underground and tap the hot rock for power. Didn’t happen for obvious reasons.)

Proponents of Orion have usually stated that it is an example of turning nuclear warhead swords into propulsion bomblet plowshares. However, if Orion proved to be the desired way to travel in space, then the production of bombs would need to be stepped up once the allowable drawdown of warheads was complete. This is no different from what would happen if nuclear power was expanded. There are enough issues with producing and transporting fissile material for nuclear reactors without compounding the risks by making and transporting small nuclear bombs. The obvious question one should be asking oneself is whether you would be comfortable with North Korea making bomblets for their own version of Orion once the technology has been proven and “commoditized”.

Then I guess humanity is going to have to settle for a rather slow boat to Alpha Centauri, because every other interstellar propulsion plan is even further off from becoming reality. I would like to be proven wrong here, but we shall see.

Well, maybe Project Longshot…

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=1708

http://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19890007533

By the time we get to start those journeys, which Dyson estimated would be centuries at 1960’s economic growth rates, we should be asking ourselves what we mean by “humanity” and where technologies might lead us.

I share SciFi author Charlie Stross that sending meat sacks to the stars is not going to work with rocket approaches. (By rocket I mean anything that works using Newton’s 3rd Law.) What makes sense energetically, is to send “seed” probes that can bootstrap themselves into functioning machines at their destination. Just as trees disperse using seeds rather than uprooting themselves and physically moving, I think that these can be visualized as von Neumann replicators of P K Dick’s autofacs.

As for humanity, at a minimum, we are talking advanced AI robots than can be created at the destination, or human DNA gestated at the target. Stross parts company with me here as he thinks advanced AGI won’t happen, so the needed humanoid nurses and teachers necessary will not be available. If human minds can be “uploaded” and “downloaded”, then that is how individuals might travel. If meat sack humans can never do this, then AI’s can travel this way if needed,

Humans or robots flitting about between the stars in large vessels seems like a rather quaint idea to me, that reflects wish fulfillment rather than reality. But if we can spread our seeds to the stars, then humanity will indeed populate the galaxy, even the universe. If I had to guess, I think the idea of separate meat sack humans and machine entities will become very blurred, with some sort of hybrid being the successful, long-lived, hyperintelligent entities we will identify as “human”. If they can copy their minds to tiny substrates, then they might join their friends and take large-ish slow boats on hazardous journeys to the stars instead of transmitting themselves.

Bottom line is that I am not in any way despondent about the lack of powerful star drives to carry us in huge starships. I see humanity circumventing the need for such energies, but with the “cost” of the individual not being able to travel, at least not initially. But a million years from now, before our current human species would have died out on Earth if we were in a pre-technological state, the galaxy might be filled with whatever humanity has become, and looking at the universe as a next step.

I actually do not envision “meat sacks” traveling to the stars when we are ready, as Artilects will be far more efficient. Humans should only go in person if we are colonizing the galaxy.

But if we can’t get even the relatively less complicated methods of interstellar propulsion to work any time soon and they are held up by multiple factors to boot, then that is a problem.

We all know there is a huge difference between observing another world via telescope and sending a probe mission directly to it. Same for exoplanets and on a much vaster scale of difference.

I have also said before that hoping or assuming the future will be better and more advanced does not mean it will be. This definitely includes assuming and hoping our descendants will learn the secrets of hyperdrive, etc. They might just as well pass the buck, too, assuming humanity’s future even continues in a progressive direction and barring any disasters.

As Arthur C. Clarke once said, what has posterity ever done for me? Exactly.

I think you are assuming that Orion is almost off-the-shelf. Development time is likely to be at least as long as StarShot, if not a lot longer. Planning horizons for a new nuclear plant in the US is probably going to be simpler.

You are talking about a huge ship, that needs to be built in orbit, and then supplied with a very large number of bomblets. Just testing it in teh solar system for a “shakedown” cruise is not going to be trivial.

I am not against “seed” missions, either. However if we want to conduct science and see a return on that investment within a human lifetime or two, we need relatively fast probe missions and not another fifty to one hundred years of further white papers, debates, and whining about why won’t the public support space exploration.

While Starshot is still speculative, it will use fast probes. I don’t see Orion going any faster. More importantly, the cost is likely to be far less than Orion in absolute terms, with a nearer term launch. Launching an Orion on a star flight will be extremely expensive by comparison. Repurposing existing warheads might save you some costs, but otherwise just building the new bombs, let alone the ship itself will be a huge economic drain. Dyson wasn’t expecting to build a star ship version for centuries.

When it comes down to brass tacks, is Starshot’s gigawatt laser going to be any different than a hydrogen bomb?

Who is going to build and – most importantly – control it? Where will the funding come from? How can we be assured it won’t be turned into a weapon of mass destruction? What if more than one nation wants t0 build their own – who is going to stop them?

No doubt antimatter propulsion will come under the same kind of attacks. After all, one kilogram of antimatter coming into contact with the same amount of matter will create an energy release equivalent to 43 Hiroshima level atomic bombs.

And this assumes we will ever be able to produce (or find) more than a few grams at mega-absurd amounts of money.

I still predict that the first manned interstellar mission will be conducted by a cult run by a superrich person who will hollow out a planetoid or comet, stock it with their followers, domesticated animals, and lots of Hot Pockets, attach some nuclear fission rockets to one end of their new home (because they don’t want the headaches of bombs, lasers, or antimatter propulsion), and head out into the wider galaxy.

They may not do any better than the guy who built Biosphere 2, but since when did that ever stop such groups from trying? And who were among the first visitors from Europe to the New World? Not a bunch of altruistic scientists, that’s for sure.

And for the record: Leonardo da Vinci’s glider only needed a rudder to work and his parachute did work in actual tests of the design. He also came up with the concepts of the robot, tank, car, and bicycle. People to this day admire his genius, they do not mock him for his ideas.

The Wright Brothers may have flown in planes we would consider quite crude today, but the point is they did it and they led the way to powered flight. The Apollo Guidance Computer is a dinosaur compared to what we compute with now, but it was impressive for its day and it did get us to the Moon. As evidenced by many comments I have seen, Orion can still knock one’s socks off and it is still the only current method we could build to get us to the stars despite all the wondrous claims I have been seeing for decades now.

I was thinking a variation on this: when you use a core in an inductor with ball bearings and apply a magnetic field the field ‘networks’ through the bearings where they physically contact. There are electric fields formed where electrons are captured in the bead core. We could use uranium (or plutonium) pellets. Applying an intense electromagnetic pulse means we can create ‘proton’ and electron propellants (hydrogen) to eject moving the space craft. None of that bomb stuff.

Theoretical: This ‘peletized core’ is what would be in the naecels of the starship enterprise except the ‘core pelets’ are going to be some sort of zero point electromagnetic bubbles in an applied electric field.

I think we all agree we need higher-energy propulsion than chemical rockets.

It’s tied on that we need nuclear propulsion of some sort. Making the fuel for such engines requires nuclear facilities on a huge scale. There is always going to be a non-proliferation consideration with all such facilities, so Orion is really no different to anything else.

Admission that Orion is too dangerous to use is a claim that humanity should never reach for the stars. Any method of star travel is going to involve energies and technologies that could devastate the earth – if Orion is out, then they all are.

That is only possibly true if you assume brute force propulsion of large ships. There are other approaches that will put human successors out amongst the stars with far less energy. After all, we can communicate across our planet without having to physically move our bodies at near lightspeed to the recipient’s location to do so.

How does one do this for less energy and yet not have to wait thousands of years for a probe to arrive at even the nearest star systems?

Does China (or any single nation) have the capability and natural resources to manufacture 300,000 one megaton H-bombs?

That scenario is just ONE option for Orion, and admittedly on the high end of the scale. The variants are mentioned in summary form here:

http://www.oriondrive.com/

“Project Orion plans were developed for craft varying in size from 300 tons (the smallest version) to 8,000,000 tons (the size of a small city). By comparison, the Shuttle orbiter has a mass of approximately 110 tons and ould carry about 30 tons of payload into low Earth orbit, and the Saturn V rocket could launch about 120 tons in low Earth orbit or 50 tons into lunar orbit.”

Throwing in this quote:

Including development and all other costs, Project Orion was estimated to be at least 20 times cheaper per pound, than any chemical rocket, at putting payload into low Earth orbit… and vastly cheaper for more distant destinations.

There are lots of links throughout my article here on Orion, plus ones with loads of details at the end of this piece. Plus note that every image shown in my article is a different Orion variant.

There were plenty of concepts for the space vessel due to the versatility of its power, which is relatively easy when you only have to reproduce them on paper. Smaller versions could have at least helped us seriously colonize the Sol system. One scenario could have carried 1,300 tons to Enceladus – and back.

Here are some more Orion scenarios, in bite size format:

http://www.astronautix.com/o/orionnuclearpulsevehicle.html

Don’t miss this article in particular:

http://www.islandone.org/Propulsion/ProjectOrion.html

Alex Tolley: By excluding all nuclear propulsion (which includes pure fusion energy, should it ever be successful), you are certainly cutting down on our options.

Even for Starshot, the power requirements for the laser array is 100 GW. Admittedly only a few minutes per launch, but there will be hundreds of launches. This is to propel a gram-scale payload at 20%c.

It’ll take a LOT of windmills to provide that kind of energy.

I thought I made it quite clear that nuclear materials in space were fine as long as they were not easily usable as weapons. Thus Orion bomblets (kT range) are not acceptable, while RTGs, nuclear reactors, nuclear rockets and fusion micropellets are all acceptable approaches. The main exception to this rule is the use of nuclear weapons to deflect/destroy asteroids for planetary defense, as their use is clearly humanitarian and a last ditch approach when other defense approaches fail.

But to make nuclear materials, you need nuclear reactors and other nuclear facilities. Tritium for fusion is made by fission reactors and is the only way of starting the tritium fuel cycle.

If you have these facilities it’s not much of a step to nuclear weapons. Look at all the fuss over Iran being able to enrich uranium.

While the Ford Motor company was dreaming of the Ford Nucleon, Chrysler came up with the nuclear-powered flying saucer for sending men to Mars:

http://www.aerospaceprojectsreview.com/blog/?p=2740

And do not think for even a moment that Walt Disney was going to be left behind:

http://atomicinsights.com/disneyland-3-14-friend-atom/

Here is some basic math and discussion.

If each bomb provides an average of 1 G acceleration for one (1) second, then 300,000 bombs will provide 300,000 seconds of 1 G acceleration. This ignores the reduction in the ship’s mass which otherwise result in a greater acceleration. Given the foregoing, the terminal velocity would be about 9,600,000 feet/second or about 1,818 miles/second which is only about 1% of C. The foregoing also ignores the negligible relativistic effects. Perhaps each blast provide 3 seconds of 1 G acceleration which would result in the claimed 3% C.