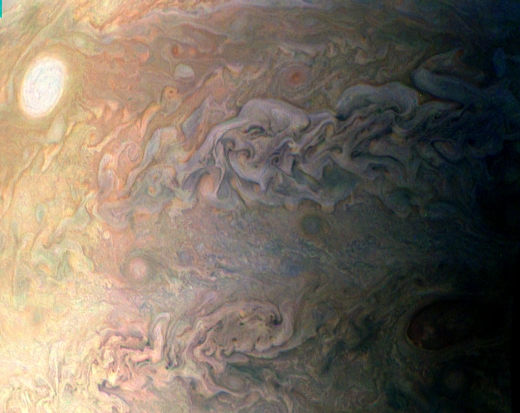

Have a look at Jupiter as seen by the Juno spacecraft on its third close pass. A view as complex as the one below reminds us how images can be manipulated to bring out detail. This happens so frequently in astronomical images that it’s easy to forget this view is not necessarily what the human eye would see, and we always have to check to find out how a given image was processed. In this case, we’re looking at the work of a ‘citizen scientist,’ one Eric Jorgensen, who enhanced a JunoCam image to highlight the cloud movement.

Image: This amateur-processed image was taken on Dec. 11, 2016, at 1227 EST (1727 UTC), as NASA’s Juno spacecraft performed its third close flyby of Jupiter. At the time the image was taken, the spacecraft was about 24,400 kilometers from the gas giant planet. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Eric Jorgensen.

The image shows a region of Jupiter southeast of what is known as the ‘pearl,’ one of eight rotating storms at 40 degrees south latitude on the planet, a region of vast and roiling turbulence. Citizen science efforts like Planet Hunters, SETI@Home and Galaxy Zoo have brought private individuals into contact with scientific data and fostered interest in a wide range of sciences, with Planet Hunters rising to particular visibility thanks to its work with Boyajian’s Star and the still mysterious light curves observed there.

The Juno mission is delving into this realm with the announcement that on the spacecraft’s February 2 pass of Jupiter, the public will have had a voice in the selection of targets for the imaging team. As JPL notes in this news release, JunoCam will begin taking pictures as Juno approaches Jupiter’s north pole. Scientists have to keep an eye on onboard storage limitations as they consider which images to collect with JunoCam. Each close pass (‘perijove’) happens in a 2-hour window as the spacecraft goes from the north pole of the giant planet to the south pole, with JunoCam imaging a circumscribed strip of territory.

The voting for the February 2 flyby is still open, but the process repeats: Each orbit will have a voting page, and each perijove on Juno’s 53-day orbit will have space for two polar images within which the public can participate in prioritizing particular points of interest, in accordance with the science goals the mission is trying to meet. Several pages at the voting site will be devoted to unique points of interest that will be within range of JunoCam’s field of view during the next close approach. Raw images will then be made available for processing.

“The pictures JunoCam can take depict a narrow swath of territory the spacecraft flies over, so the points of interest imaged can provide a great amount of detail,” said Juno co-investigator Candy Hansen, (Planetary Science Institute). “They play a vital role in helping the Juno science team establish what is going on in Jupiter’s atmosphere at any moment. We are looking forward to seeing what people from outside the science team think is important.”

Bear in mind that JunoCam was included on the mission because, working in color and visible light, it could offer a wide field of view that would, among other things, spur public interest and involvement. So it’s not surprising to see this citizen science angle being brought forward, offering engagement not just from amateur scientists but students worldwide. Building public support is also a key component in keeping up the pressure for better space funding.

The February 2 flyby makes its closest approach to Jupiter at 0758 EST (1258 UTC), with the spacecraft about 4300 kilometers above the cloud tops. We’ll see Jupiter up close once again through a spacecraft’s lens, translated for us into images that mimic what we would see with our own eyes before we get to work processing them. If you’re interested in having a say on future JunoCam targets, click here for information on how to get involved.

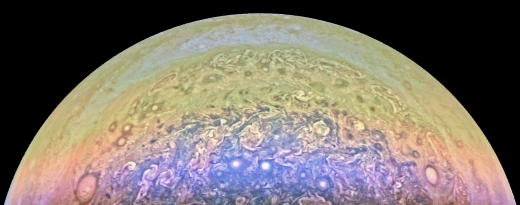

Image: Jupiter’s south pole as seen during perijove 3, in an image processed by Julien Potier (Planetario Silvia Torres Castilleja, Ags, Mexico), rotated, cropped to get rid of yellowish band, processed with RGB levels, brightness, contrast and HDR Toning.

I sincerely hope Eric(or someone ELSE)can process the image of Occatoer Crater on Ceres that proved(BEYOND A DOUBT now)the existance of haze ABOVE the surface! Not to get TOO OT, but the existence of water vaper was also confirmed, reconciling the Herschel observations a couple of years ago! Since “haze” is defined as DRY PARTICLES(dust, smoke, etc.), it begs the question: what ARE those dry particles. Probably salts(washing soda, baking soda, etc.) that then pile up on the surface, although NO MENTION OF THAT was made. Another intreguing possibility is that the haze could be composed of flash-frozen micro-organisms. A follow-up mission to determine if this is the case should be funded and planned IMMEDIATELY!

The Jovian system is absolutely fascinating. When we get a probe onto Europa it will deliver vast amounts of information about a huge moon with a potential for life in its subsurface ocean. One of the great missions of this century I would think.

What is the current thinking about the possibility of life in the Jovian atmosphere? Looking at the amazingly intricate swirls of color, one might be forgiven for naively imagining biology to be involved. Are there altitudes, as with the Venusian atmosphere, at which biology-friendly combinations of temperature and pressure coincide?

When Jupiter was forming it was very hot, much too hot for life, it is much cooler today but it does have a high gravitational field. This high gravitational field gives incoming material a high impact velocity and therefore very, very high heat loads. Life could however have come from one of its moons by been chipped off or could have been created with chemicals and lightning in the atmosphere as it cooled. So life is possible, we could see if life could survive in the atmosphere of Jupiter by simulation in a lab though. I think life forms would survive in Jupiter’s current conditions but I am not sure if it could have spontaneously be created as there are too few chemicals and metals to help and continue the process as we know it or I know it.

http://tpr.org/post/juno-spacecraft-rewriting-what-we-know-about-jupiter#stream/0

Juno Spacecraft Is Rewriting What We Know About Jupiter

By PAUL FLAHIVE • FEB 27, 2017

To quote:

“Maybe they’ll see this? Maybe Juno will see that, but none of them have been as out of the box as what we are seeing,” says Bolton

For instance, Bolton points to Jupiter’s core. Many models predicted a rocky core of heavy elements about the mass of Earth, but after a couple of orbits it became clear the core was not what they thought.

“We don’t see anything that looks like a core. There may be a core of heavy elements in there, but it might not be all concentrated in the middle. So that was the first picture that started to go out the window. And we started to say, you know, what would the core be like? Maybe it’s much larger? Maybe it’s half the size of Jupiter? How could that be?” Bolton asks.

Jupiter looks like an abstract painting in NASA Juno image

Jupiter’s swirling atmosphere gets a gorgeous watercolor-like close-up from NASA’s Juno spacecraft.

https://www.cnet.com/news/jupiter-nasa-juno-close-up-atmosphere/

The latest artwork from Jupiter via Juno:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2017/20170327-treasures-from-jupiter.html

And to think this camera was an add-on to the Juno mission. Every space expedition should realize by now that if you don’t send back images you can pretty much forget publicity and future funding.

New Scientist – Daily news

3 May 2017

First results from Jupiter probe show huge magnetism and storms

By Andy Coghlan in Vienna, Austria

Big planets come with big surprises. Last week, delegates at the annual European Geosciences Union meeting got the first glimpse of data from the Juno spacecraft now in orbit around Jupiter, and the findings are already challenging assumptions about everything from the planet’s atmosphere to its interior.

“The whole inside of Jupiter is just working differently than our models expected,” said mission principal investigator Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in Texas.

Launched on 5 August 2011, Juno reached Jupiter and began its first orbit on 4 July last year. Since then, it has performed four more circuits. There are 33 planned pole-to-pole circuits in all, encircling the entire planet bit by bit.

The findings presented in Vienna come from these first few circuits, which each last 53 Earth days and include a 6-hour scan of the planet from north to south. Although the information is preliminary, the researchers involved are thrilled.

Full article here:

https://www.newscientist.com/article/2129805-first-results-from-jupiter-probe-show-huge-magnetism-and-storms/

To quote:

The findings are also challenging models of what’s inside the planet. We had assumed Jupiter has a uniform interior, with a shallow “crust” of liquid hydrogen overlying a thin layer where helium rains down. Under that is a much deeper layer of metallic hydrogen, with a smaller solid core around 70,000 kilometres down. Those assumptions were based on mapping the planet’s gravity.

But initial gravity measurements from Juno challenge the idea that the internal layers inside are completely regular in their make-up. “Jupiter’s molecular envelope is not uniform,” said Tristan Guillot of the University of the Cote d’Azur in France. “We assumed we could treat the envelope as global, but now, with the finer data, it appears less regular.”

Fletcher says it points to a core that is not solid like Earth’s, but “fuzzy” and dilutely mingled with the overlying metallic hydrogen layer.

Juno to fly right over the Great Red Spot on July 10:

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2017-186

To quote:

The data collection of the Great Red Spot is part of Juno’s sixth science flyby over Jupiter’s mysterious cloud tops. Perijove (the point at which an orbit comes closest to Jupiter’s center) will be on Monday, July 10, at 6:55 p.m. PDT (9:55 p.m. EDT). At the time of perijove, Juno will be about 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers) above the planet’s cloud tops. Eleven minutes and 33 seconds later, Juno will have covered another 24,713 miles (39,771 kilometers) and will be directly above the coiling crimson cloud tops of Jupiter’s Great Red Spot. The spacecraft will pass about 5,600 miles (9,000 kilometers) above the Giant Red Spot clouds. All eight of the spacecraft’s instruments as well as its imager, JunoCam, will be on during the flyby.

Earth-based astronomers will be helping Juno on its flyover of the GRS on July 1o:

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2017-185