I don’t want to get much deeper into February without looking at the recent Cassini imagery from Saturn’s rings. Cassini, after all, is a precious resource, and every day that passes brings us closer to its mission-ending plunge into Saturn’s cloud tops this September. Leading into that climactic event, however, we have the current ring-grazing orbits, a mission segment that is about half completed. Mission’s end gives us the chance to see the rings in exquisite detail.

20 orbits are involved in the ring-grazing phase, each diving past the outer edge of the main ring system, before things get even more dramatic, and the so-called ‘grand finale’ begins. The latter is to include 22 orbits that will take Cassini through the gap between the rings and Saturn itself, with the first plunge scheduled for April 26. The payoff is immense: We’ve never had views as close or as dramatic of small moons like Daphnis, seen in the image below.

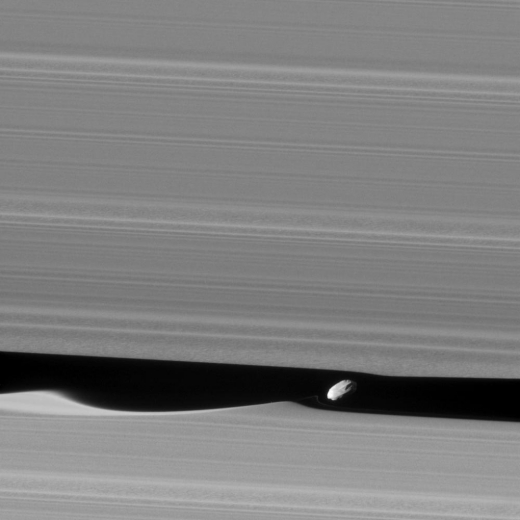

Image: The wavemaker moon, Daphnis, is featured in this view, taken as NASA’s Cassini spacecraft made one of its ring-grazing passes over the outer edges of Saturn’s rings on Jan. 16, 2017. This is the closest view of the small moon obtained yet. Daphnis (8 kilometers across) orbits within the 42-kilometer wide Keeler Gap. Cassini’s viewing angle causes the gap to appear narrower than it actually is, due to foreshortening. The little moon’s gravity raises waves in the edges of the gap in both the horizontal and vertical directions. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

The interactions between moon and ring are particularly interesting here. In several wide lanes in the ring, we seem to be seeing structures where particles have clumped together, marked by their grainy texture. At the left of the moon as seen in the image, the edge of the Keeler Gap appears softened, which scientists speculate is due to the movement of ring particles into the gap after Daphnis’ most recent approach on the orbit before this one.

When Cassini arrived at Saturn back in 2004, we also were able to work with a high level of ring detail, seeing features called ‘straw’ and ‘propellers’ that were the result of ring particles clumping and interactions with embedded, tiny moons. I had to go back and look at my notes on this — Cassini, as noted in this JPL news release, actually closed to an even tighter distance from the rings during the Saturn arrival, but the imagery it sent back was not as good because of the need to use short exposure times to avoid smearing due to the spacecraft’s motion over the ring plane.

The current views are taken in both the backlit and sunlit side of the rings, and we have dozens of passes to work with as the mission nears its terminus. Carolyn Porco (Space Science Institute, Boulder CO) is imaging team lead:

“As the person who planned those initial orbit-insertion ring images — which remained our most detailed views of the rings for the past 13 years — I am taken aback by how vastly improved are the details in this new collection. How fitting it is that we should go out with the best views of Saturn’s rings we’ve ever collected.”

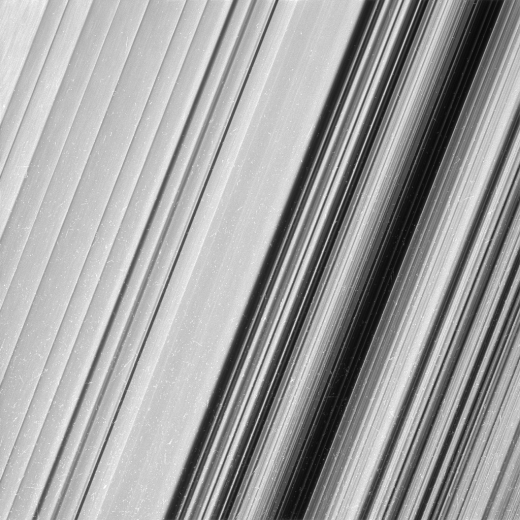

Image: This image shows a region in Saturn’s outer B ring. NASA’s Cassini spacecraft viewed this area at a level of detail twice as high as it had ever been observed before. And from this view, it is clear that there are still finer details to uncover. Researchers have yet to determine what generated the rich structure seen in this view, but they hope detailed images like this will help them unravel the mystery. In order to preserve the finest details, this image has not been processed to remove the many small bright blemishes, which are created by cosmic rays and charged particle radiation near the planet. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

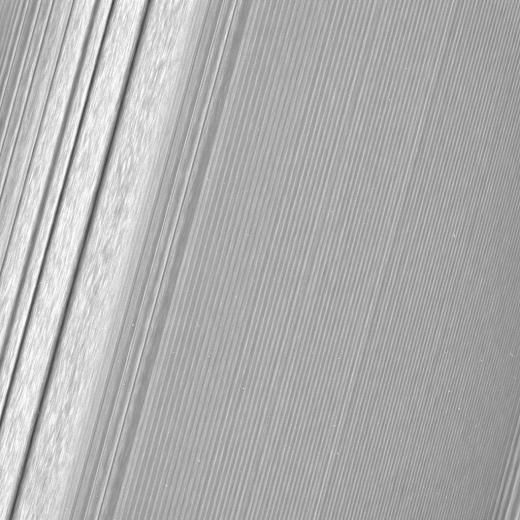

The image below, also only lightly processed, was taken in visible light with Cassini’s wide-angle camera on December 18, 2016. Here we’re looking at a distance of approximately 56,000 kilometers, with an image scale of about 340 meters per pixel.

Image: This Cassini image features a density wave in Saturn’s A ring (at left) that lies around 134,500 km from Saturn. Density waves are accumulations of particles at certain distances from the planet. This feature is filled with clumpy perturbations, which researchers informally refer to as “straw.” The wave itself is created by the gravity of the moons Janus and Epimetheus, which share the same orbit around Saturn. Elsewhere, the scene is dominated by “wakes” from a recent pass of the ring moon Pan. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute.

On a personal note, Cassini was much in my thoughts during its final insertion into Saturn’s orbit, which it entered on July 1, 2004. During the approach to the planet, all I could think about was that we were trying to put a spacecraft through a gap between two of Saturn’s rings — the F and G rings — using a complicated maneuver that involved spacecraft rotation to shield its instrumentation from ring particles followed by a decelerating engine burn.

Actually crossing Saturn’s ring plane to do this seemed like science fiction come to life. At the same time that year, I was working on getting Centauri Dreams up and running, trying to figure out the software and making choices about hosting providers, all the stuff people do when they’re trying to create an online publication. For me, the Cassini arrival and Centauri Dreams will always be inextricably linked.

Also linked: Donald Wollheim’s 1954 novel The Secret of Saturn’s Rings, one of the Winston juveniles that many of us absorbed as space-struck kids. I have a suspicion that at least a few of those now working Cassini’s ring passage have a happy memory of this title. I hadn’t recalled the book in decades, but these ring-crossing orbits brought it all back. Nice Alex Schomburg cover!

One or two questions concerning this mission and its plunge through the rings to study it in detail:

Paul, my first question concerns the safety of the craft as it makes its way through the gaps in the rings; do you have any idea how they justify the idea that there could be a pebble or dust particles that could impact the craft and destroy it ? Do you know any of the reasoning behind their assessment that this is a safe procedure to do ?

Yet the question is far more important to me from the standpoint of mechanics, there’s some kind of reason (physical) why the rings that surround the Saturnian body cannot be solid material body in terms of their structure. If memory serves me correctly, it may be due to the fact that a solid ring in orbit about the planet would be subject to tidal forces which would serve to rip the ring apart; is this information as I recall, is that the valid reason for this to be composed of innumerable separate rings ?? Do you know anyone Paul who can answer that question ?

We’ve gotten a pretty good idea about what to expect at Saturn thanks to Cassini’s travels; remember that it went through a ring gap just to achieve its initial orbit at Saturn. It’s now grazing the outside of the rings, and will eventually move between the rings and the planet. I don’t have references on our studies of this area, but so far the Cassini team has been right about where it was safe to move the spacecraft. Anything can happen, but let’s hope that the area between rings and planet is also safe.

On the matter of ring or larger object stability in these orbits, I’ll have to let others have a crack at it. I assume the Roche limit will be part of the discussion:

http://www.jgiesen.de/astro/stars/roche.htm

To me the best image remains the one of the “mountains on the rings”:

http://ciclops.org/view/6480/The-Tallest-Peaks?js=1

“The Secret of Saturn’s Rings”! I loved that book whenI was a kid. Couldn’t put it down. And I seem to remember that at the end, they fly away back toward Earth in an alien spaceship they discovered inside a structure (or hollowed out feature) on one of the Saturnian moons. The aliens apparently went through a phase of designing 1950s style sci-fi spaceships, easily flown by Earthlings!

Yes, as I recall they landed on Mimas and found the ruins of an ancient visitation there. A gripping tale in its day, and one I’ll always recall with fondness.

In the Arthur C. Clarke novel version of 2001: A Space Odyssey from 1968, the second Monolith/Stargate sat in a ring on the moon Iapetus, which even back then was recognized as unusual being 6 times brighter on one hemisphere than the other. A good way to get one’s attention from space.

You’ll notice they put off repeated trips through the rings till near the end. I presume there wasn’t much choice about that first one, but I’ll bet there was gnashing of teeth.

What little I think I know of orbital mechanics says the lower you are, the faster you go. So over even thousands of years rocks near each other would drift apart. I think that’s pertinent to the ability of a solid ring to last, maybe not to why there are so many separate rings.

What was the secret in The Secret of Saturn’s Rings? Spoiler requested.

You want bizarre alien moons? Pan is a major contender:

https://www.nasa.gov/image-feature/jpl/cassini-reveals-strange-shape-of-saturns-moon-pan

Another one is Methone:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2012/05211206.html

Cassini, with only a half-year to go at Saturn, just keeps dropping awesome images

Posted By Jason Davis

2017/03/09 17:38 UTC

Topics: pretty pictures, Cassini, Saturn’s small moons, Saturn’s moons, Saturn

The Cassini mission at Saturn ends in 6 months and 5 days.

On September 15, after 13 years in orbit, Cassini will plunge into Saturn’s atmosphere, preventing it from accidentally colliding with the potentially habitable moons of Enceladus and Titan.

Right now, the spacecraft is in the midst of 20, ring-grazing orbits, after which it will maneuver itself into a path that will take it between the rings and the planet itself on April 22.

At the moment, Cassini’s outer ring orbits are revealing some wild, high-resolution shots of some of Saturn’s most enigmatic worlds. Most recently, this included new looks at 35-kilometer-wide Pan. On March 7, Cassini got its best view yet of the ravioli-shaped moon, which orbits inside the A ring’s Encke gap.

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/jason-davis/2017/20170309-cassini-drops-amazing-images.html

The latest on Cassini final days at Saturn, which start on April 22:

https://www.universetoday.com/134795/cassinis-final-mission-annihilation-starts-april-22/

To quote:

There’s the risk of dust or debris hitting the spacecraft, potentially crippling Cassini. But the risk is worth it, because if the spacecraft survives through even just a few of the close passes, the scientific payback will be incredible. However, even if the spacecraft is crippled and can’t send back its final science observations, the end is inevitable, as the path toward destruction will be written by the final ‘kiss’ from Titan.