What kind of civilization might eventually emerge on Mars? Colonies of various kinds have been examined in science fiction for decades, but as we close in on the possibility of actual human arrival on the planet, perhaps in the 2030s, we can wonder how living on a different world will change the people who eventually choose to call it home. The prolific Nick Nielsen likes to take the long view, arguing in the essay below that while there are contrasting definitions of civilization itself, we may yet learn through experiment and experience how a ‘central project’ emerging from local conditions may define the future of colonies on other worlds. Human history offers guidance, but it may be that a successful Martian colony will see its position as a gateway to the exploration of the Solar System. You can follow Nick on his Grand Strategy: The View from Oregon site, as well as his Grand Strategy Annex.

by J. N. Nielsen

Settling Mars

Suppose that one or several planned large-scale missions to Mars come to fruition over the next few decades. Perhaps the first mission or missions are temporary scientific visits that endure a few weeks or months and then Mars is left vacant again. Even if it is only a handful of individuals temporarily on Mars for a few weeks or a few month of exploration, the camaraderie unique to these early Mars missions will be the first intimation of a distinctively Martian social milieu.

Beyond the transient exploration of a scientific mission, the vision of several Mars mission planners includes settlement, and these plans, if realized, will mean that eventually there will be large numbers of human beings living and working on Mars. We may see a patchwork of multiple settlements and multiple temporary scientific missions, existing side-by-side, each pursuing their own ends in their own ways. Some of the early explorers may chose to return and to remain, their lives having been touched and irrevocably changed by their initial encounter with the Red Planet.

In the case of an ongoing human presence, the numbers of human settlers will grow, eventually also they will become self-supporting and self-sustaining. Whether or not they formally declare their independence, they will be independent for all practical purposes. Given these eventualities, at some point we will need to recognize that an independent and distinctive Martian civilization exists. At what point in its development would we recognize a Martian civilization? What will be the character of this civilization?

Image: A lone explorer on Mars by Italian digital artist Alberto Vangelista.

A Martian Perspective

In the classic science fiction film Forbidden Planet there is a striking scene early in the film in which two characters discuss the color of the sky, and one says, “I think a man could get used to this and grow to love it.” Will Martian settlers get used to the red skies of Mars and grow to love it?

Whether or not they love the red skies of the Red Planet, these red skies will be a fact of life on Mars no less than the red sands under foot. These Martian facts of life will collectively shape a distinctive Martian perspective, and a Martian civilization will grow out of a uniquely and distinctively Martian perspective. In What will it be like to be a Martian? I have already discussed that there will be something that it is like to be a Martian (borrowing from Thomas Nagel’s famous formulation that there is something that it is like to be a bat [1]), and in The Martian Standpoint (and Addendum on the Martian Standpoint) I discussed the emergence of a distinctively Martian perspective.

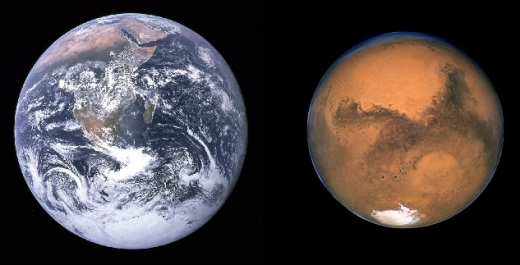

This perspective will be marked by properties in common with terrestrial civilization (such as being human) as well as properties not shared with terrestrial civilization (living life under a red sky, being able to pick out Earth in the night sky, having to wear a pressure suit outside, and so on). Most of that which is in common with terrestrial life will pass unnoticed, but the differences will be prominent in the minds of Martian settlers precisely because the differences will stand out against the background of unnoticed similarity.

Mars itself, its gravity, its weather, its seasons, the length of its day and coolness of the sun in the sky, as well as the adaptations that the settlers will have to make in order to live on Mars, will become selection pressures that will shape the social life of these communities. An individual human being who experiences what it is like to be a Martian, and who, as a consequence of living on Mars, has a Martian perspective, will be an individual participating in a community, all of whom are experiencing what it is like to be a Martian and to have a Martian perspective. Pride in being first on Mars will be mixed with equal parts homesickness, and, just so, every aspect of human moral psychology will find itself tested by the tension between old and new. From this dialectic will emerge an outlook unique to Mars, the Martian perspective, and this Martian perspective will inform all aspects of social life, from the most intimate introspection to the most public debates on what kind of society the Martians should build for themselves.

As the Martians go about building the economic infrastructure of Martian civilization, an intellectual superstructure will come into being in parallel with the built environment, and infrastructure and superstructure will be inseparably joined by the central project of Martian civilization, which at first will simply be the attempt to build a self-sustaining and self-supporting human presence on Mars. [2] What form the central project of Martian civilization will take after this initial goal is achieved cannot now be known. Martian society will be sufficiently small that it could be comprehensively motivated and unified by a central project, and the population of Mars will be sufficiently self-selected for scientific acumen and practical ability that whatever central project naturally grows out of the combined exertions of this population is likely to be as distinctive as the self-selected conquistadors who came to South America and the self-selected Puritans who came to North America.

A Tale of Two Planets: Terrestrial Civilization and Martian Civilization

Civilization on Earth has already passed through many stages of development, and it is at least arguable that at least some terrestrial civilizations have reached maturity, but a nascent civilization on Mars, while an heir to these mature traditions of terrestrial civilization, would be an entirely novel enterprise. The Martian civilization will be a new civilization, and as a new civilization it will begin its social development at its inception; it will not be a mature civilization of long-established institutions, but a tentative experimentation in institution building and in ways of life possible on Mars.

When a civilization originates in a given historical epoch, that historical epoch is expressed in that civilization, so that the civilization of classical antiquity expressed the world of the ancient Mediterranean Basin and the civilization of medieval Islam expressed the world of seventh century Arabia and the civilization of the industrial revolution expressed Enlightenment era northern Europe. Martian civilization, coming into being in the twenty-first civilization, would emerge from a radically different social context than any of these previous civilizations, and so it would express a radically different world than civilizations of the past. Martian civilization, then, could be a new civilization in more than one sense. It would also be a civilization de novo.

Image: Workshop of Filippe Maëcht and Hans Taye. Constantine Directing the Building of Constantinople. 1623-1625. Wool, silk, gold and silver. 484 × 480 cm (190.6 × 189 in). Philadelphia.

De novo civilization

For quite some time I have been planning to write about the possibility of what I call de novo civilization, i.e., civilizations that are newly constituted, but are distinct from those civilizations with which civilization began on Earth. The earliest civilizations in the world—the West Asian Cluster (Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Egypt, etc.), Mesoamerican, Peruvian, Chinese, and Indian civilizations, at a minimum—were all de novo civilizations, originating as something entirely new in the history of the planet. These original civilizations might be called “founder” civilizations, as they were the founders of all civilizations to subsequently follow.

Descended from these “founder” civilizations were a greater or lesser number of subsequent civilizations—depending upon the principles we adopt to individuate and therefore count civilizations—that were derived from the founder civilizations through descent with modification, through idea diffusion, through allopatric speciation, and so on. By identifying de novo civilizations as new civilizations distinct from this small, finite class of founder civilizations, I am suggesting that a new civilization can come into being through a new foundation (or a re-foundation) of some existing civilization. What particularly interests me most are those civilizations that “suddenly” come into being as the result of some relatively rapid historical change. Martian civilization would be such a de novo civilization arising from a new foundation.

The best example I can offer of de novo civilization is that of Byzantium. The Byzantine Empire is typically identified as becoming a distinct entity sometime between Constantine’s foundation of Constantinople (on the site of the earlier Greek city of Byzantium) in 330 and the reign of Justinian during the sixth century AD. Constantine spared no expense in furnishing his new Christian capital city, endowing it with art and sculpture essentially looted from other much older cities. An urban proletariat was even imported to populate the new metropolis. Eventually Greek speaking, and eventually Orthodox in its Christianity, Constantinople and the distinctive Byzantine civilization over which the city presided had inherited the traditions of Roman civilization, and as the city grew in size and influence there was no “breakdown” of trade or communication that isolated the region. When the last legal emperor of the western Roman Empire, Romulus Augustulus, surrendered control of Rome to the barbarian king Odoacer, the imperial insignia were sent to Constantinople for safekeeping. Thus Byzantium, still in touch with its parent civilization, nevertheless speciated and became its own distinctive civilization, different from Rome even while continuing to self-identify as Roman.

So it will be, I think, with Martian civilization, which will become its own distinctive civilization even while continuing to self-identify with essential elements of terrestrial civilization. The selection pressures upon terrestrial and Martian civilization will be so markedly different that the speciation of Martian civilization from its parent terrestrial civilization is nearly inevitable, although there will be ongoing commerce, communication, and conflict between Earth and Mars. Martian civilization will emerge as a de novo civilization even in the absence of a rupture between Earth and Mars; the transfer of some portion of terrestrial civilization to a human population on Mars will be sufficient for a new foundation of civilization, even if this is not what is intended.

Image: Prehistorian V. Gordon Childe at Skara Brae, Orkney.

V. Gordon Childe’s “urban revolution” on Mars

One of the most influential accounts of the origin of civilization is that of V. Gordon Childe, and, ironically, it was not explicitly cast as an account of civilization, but rather of the “urban revolution,” i.e., the origin of cities. [3] There is a vast literature on Childe’s “urban revolution” and it has become a commonplace among archaeologists, especially those archaeologists formulating theories about the origins of civilization, to employ Childe’s ten criteria for the urban revolution as a definition of civilization: something is a civilization if it possesses most of the items on Childe’s list. [4] Subsequent prehistorians have tinkered and tampered with Childe’s model, but for the most part it remains intact and continues to influence archaeological thought about civilization even today.

While Childe does not himself assert that the properties he identifies as characterizing the urban revolution constitute a definition of civilization, he may as well have said so, as this is the lesson that has been taken from the paper. In so far as “urban revolution” implies the revolutionary appearance of many cities, the lesson is justified. A rough characterization of civilization could be a network of cities actively engaged in cooperation and conflict with each other. [5] We see this pattern clearly in Mesopotamia, in Mesoamerica, in the Indus Valley, and will probably find it wherever civilization independently emerges.

Following this example, when there are a network of settlements on Mars actively engaged in cooperation and conflict with each other (as in the suggestion above that Mars may be a patchwork of settlements both temporary and permanent), we could at that point identify a Martian civilization. As Martian civilization grows, it will unify itself as a planetary civilization, all of which evolves under the uniform physical selection pressures of the planet, just as terrestrial civilization has evolved under the uniform selection pressures of Earth. On Mars, communication between regions of the planet will be nearly instantaneous, as is communication on Earth today, and the immediate neighborhood of Mars, its satellites and space stations, will also be a part of this instantaneous communications network. Mars will have its own internet, which will presumably be updated on a regular basis, much like a backup system where Mars and Earth each back up the other. Martian social media will be dominated by “Martian issues” just as terrestrial social media will be dominated by terrestrial issues.

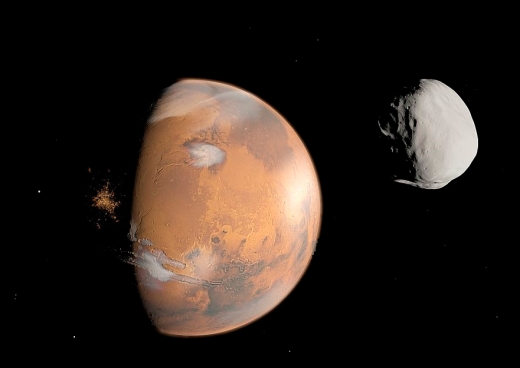

Image: Mars may come to be the origin of a spacefaring civilization. (Mars from the Moon Phobos by Jack Coggins, 1951).

Two planetary civilizations projected onto the cosmos

A planet is a natural unit for civilization, which I have expressed elsewhere by saying that planetary civilization is the natural teleology of civilization. [6] Beyond the scope of a planetary civilization communication will experience relativistic delays that become longer the more distant the parties to the communication. There will be communication between Mars and Earth, of course, but of a stilted and somewhat awkward variety, as there will be trade, probably a trickle of luxury goods (rather than staples) as once slowly moved along the Silk Road tenuously connecting the ancient east to the ancient west. Communication and commerce, however, will underscore rather than unify the natural planetary units of Earth and Mars. Exactly what is communicated and what is traded (as well as what is not communicated and what is not traded) will define a system of meanings and values, and these systems will be different on Earth and Mars. [7]

We can always formulate a more comprehensive conception of civilization that includes both terrestrial civilization and Martian civilization—presumably this more comprehensive conception will be “human civilization” as this conception will of necessity be based on those properties shared in common between terrestrial and Martian civilization—much as we can today speak of a planetary civilization that encompasses the many regional civilizations that have grown together as human transportation, communication, and commerce networks have come to integrate the planet entire. Perhaps this more comprehensive conception of civilization could also be called a de novo civilization. With planetary civilization converging on totality, the next stage of emergence in large-scale social organization will be the interaction of these distinct planetary civilizations—the civilizations of Earth, Mars, the moon, and elsewhere, including clusters of artificial habitats.

The expanding scope of large-scale social organization, from a network of cities involved in cooperation and conflict to a network of planets involved in cooperation and conflict and eventually a network of planetary systems engaged in cooperation and conflict, define stages in the development of a cosmological civilization. The civilization that we may yet build within our own solar system will be a model in miniature of an interstellar civilization in which it is a network of planetary systems engaged in cooperation and conflict that defines large-scale social organization. In this context, the different between terrestrial and Martian civilization may become significant.

In the settlement of the New World it is interesting to note the difference between those regions settled directly by European peoples and those regions settled not from the Old World, but from earlier settlements. Thus while New England was settled by Puritans from England, the Carolinas were settled by Caribbean planters. [8] Sugar cane was such a lucrative crop that every scrap of available ground on the Caribbean islands was planted in sugar cane plantations, but these plantations in turn needed to be supplied with foodstuffs and building materials, and so the Carolinas were settled in order to produce the sustenance and material goods required by the export-oriented monoculture of sugar plantations in the Caribbean. [9] The cultural differences between these regions persists to the present day, and is likely to continue to persist into the foreseeable future.

It would be reasonable to expect that a similar pattern will reveal itself in the settlement of the solar system, with some colonies being established directly from Earth, while other colonies may be established by Martian and Lunar settlements, once these latter have reached a sufficient state of development that they can mount outward colonization efforts themselves. [10] In this way, the characteristic differences between terrestrial and Martian civilization will be perpetuated throughout the solar system, and perhaps even throughout the galaxy, and may persist long after any rivalry between Earth and Mars is politically relevant.

But will it ultimately be terrestrial or Martian civilization that leaves the greatest imprint on the universe? The fact that Martians will have already made the leap from Earth to Mars, representing the first spacefaring diaspora, and the likely disproportionate scientific and technological knowledge and expertise in the Martian population to come, will predispose Martians to a central project for their civilization based on spacefaring. Once the Martians have assured their survival and independence, the solar system will be at their doorstep. Mars is the perfect base for a spacefaring civilization, with the lower gravity making the construction of a space elevator easier than on Earth, and being positioned close to the asteroid belt Thus even if a scientific and spacefaring civiization does not fully emerge on Earth, social conditions on Mars may be more favorable to such a development.

——————————————————-

Notes

[1] Thomas Nagel, “What is it like to be a bat?” The Philosophical Review, LXXXIII, 4 (October 1974): 435-50.

[2] I sometimes define civilization as an economic infrastructure joined to an intellectual superstructure by a central project. I regard this formulation as tentative. Mass societies may be too large and too diverse to be defined by a single central project, so a mass society may have several central projects, but no single, dominant project—or it may have no central project at all. Prior to the advent of mass society, regional civilizations (not yet having converged on planetary scale) were almost always strongly marked by a central project, which almost always was soteriological or eschatological in nature.

[3] V. Gordon Childe, “The Urban Revolution,” The Town Planning Review, Vol. 21, No. 1 (Apr., 1950), pp. 3-17. (Careful observers of the Indiana Jones films will notice that the archaeologist protagonist of the films cites V. Gordon Childe.)

[4] In brief, Childe’s list includes, 1) extent and density of settlements, 2) division of labor, i.e., craft specialization, 3) surplus value transferred to social elites (which might also be called “capital accumulation”), 4) monumental architecture, 5) social stratification, 6) writing, 7) science, 8) art, 9) trade, and 10) prioritizing residence over kinship. I briefly touched on Childe’s conception of civilization in terms of the urban revolution in my talk at the 2015 Starship Congress, “What kinds of civilizations build starships?” in which I also gave an exposition of my understanding of economic infrastructure and intellectual superstructure (cf. note [2]).

[5] Above in note [2] I said that I sometimes define civilization as an economic infrastructure joined to an intellectual superstructure by a central project; I also sometimes define a civilization as a network of cities bound by relationships of cooperation and conflict. I regard all of these formulations as tentative; the definitive definition of civilization has yet to be formulated. The definition of civilization in terms of a network of cities is obviously a practical characterization that could be established by means of archaeology; a definition of civilization as a central project linking infrastructure and superstructure is much more abstract, and for the same reason it is much more likely to be adaptable to unforeseen developments in the future.

[6] The assertion that planetary civilization is the natural teleology of civilization may be true for only one historical stage in the development of civilization (I explored this idea in Counterfactual Suboptimal Civilizations of Planetary Endemism and Addendum on Civilizational Optimality). It could be argued that the natural extent of a civilization grows over time, so that the earliest manifestation is a city-state with a surrounding region, then an empire, then a regional civilization, then a planetary civilization, then a system-wide civilization, and so on.

[7] These systems of meanings and values constitute part of the intellectual superstructure.

[8] Similarly, in South America Chile was settled for purposes of supply rather than monoculture export.

[9] New England also came to rely on export-oriented monoculture, but of tobacco rather than sugar, especially the “tobacco colonies” of the Chesapeake Bay region. While Caribbean islands were not large enough both to produce sugar for export and to produce their own food, there was sufficient land in New England for both export and staple crops.

[10] It is to be expected that most if not all of the earliest settlement enterprises will be financial failures, if historical analogy holds: “Many early colonial adventures—like Cartier’s voyages, the Panfilo de Narvaez expedition, and Raleigh’s Guiana and Roanoke projects—were characterized by gigantic losses. By the end of the 1620s every single English colonial company had failed both financially and organizationally, and every single early French trading company had been dissolved; by 1674, the Dutch West Indies Company had gone bankrupt for the first of two times.” (A Companion to the Literatures of Colonial America, edited by Susan Castillo and Ivy Schweitzer, p. 64)

We Need to Stop Talking About Space as a “Frontier”

The language we use matters, especially when it’s deployed in the service of envisioning possible futures.

By Lisa Messeri

http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/future_tense/2017/03/why_we_need_to_stop_talking_about_space_as_a_frontier.html

To quote:

The frontier language challenged the government to make a sustained push toward settlement and exploration ever farther from Earth. But following the end of the Apollo program in 1972, it became clear that the government was not going to fulfill the promise of the frontier metaphor. Eugene Shoemaker, who was involved in astronaut training, described in an oral history interview how he once tried to compare the American West with Apollo to encourage NASA not to retreat from the new frontier. In the end, Shoemaker reflected, “the early exploration of the American west led to evolving, continuing, growing scientific enterprise. The Apollo program didn’t.”

In this leadership void, other individuals and groups picked up the frontier mantle. Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill repeatedly tried to get NASA and the broader public interested in long-term, off-planet human space settlement. The first book in which he outlined this vision was The High Frontier, published in 1976. O’Neill’s research engendered a fierce following, and in 1988, a few of these acolytes (including Tumlinson) founded the Space Frontier Foundation intent on pursuing this vision of space colonization outside of the traditional, government-funded route.

So are we going to just wait for Phobos and Deimos to either get torn apart or crash onto Mars, or are we going to utilize them properly for the Martian colonies?

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?release=2017-075

Or maybe they would make dandy interstellar arks.

If we want to establish a civilization on Mars, first we have to be able to stop crashing on it on a regular basis:

http://m.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/ExoMars/Schiaparelli_landing_investigation_completed

Schiaparelli did more things right than it did wrong

The European Space Agency released last week a summary of the final report investigating the crash of its Schiaparelli Mars lander last year. Svetoslav Alexandrov argues that the report shows that the mission should not be dismissed as a total failure.

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/3251/1