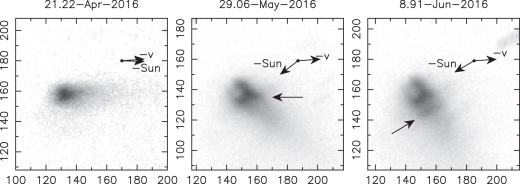

You wouldn’t expect main belt asteroids to develop tails like comets — their orbits are circular enough that they don’t undergo the kind of temperature swings many comets experience in their plunge toward perihelion — but we do have some twenty cases of asteroids that do exactly that. The photo below, showing imagery from the 10.4-meter Great Canary Telescope, gives us views of asteroid P/2016 G1, with a smudgy dust trail splayed out behind the object.

Image: Asteroid P/2016 G1 at three different times in 2016: late April, late May and mid June. The arrow in the center panel points out an asymmetric feature that can be explained if the asteroid initially ejected material in a single direction, perhaps due to an impact. Credit: Fernando Moreno (Institute of Astrophysics of Andalusia, Spain).

Moreno and team, who have specialized in the dust environment near main belt objects, have now uncovered another intriguing asteroid, this one with an even more curious tail. Asteroid P/2016 J1 turns out to be an asteroid pair, of a kind that seem to occur not infrequently in the main belt. The likely origin of the pair is an impact that broke a single asteroid into two parts, but astronomers studying the object also believe it could have fragmented because of an excess of rotational speed. Asteroid pairs gradually drift apart from each other, their gravitational link not strong enough to hold them together, but they remain in roughly similar orbits around the Sun.

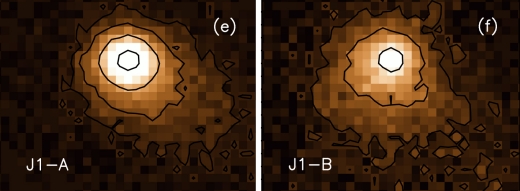

Image: Images of the P/2016 J1 asteroid pair taken on May 15th, 2016. They show a central region, the asteroid, and a diffuse blot corresponding to the dust tail. Credit: Moreno et al.

Moreno notes what makes P/2016 J1 unusual: Both fragments show dust structures similar to a comet, making this the first time we have seen an asteroid pair undergoing simultaneous activity. Both elements of the pair became activated near perihelion, between the end of 2015 and the beginning of 2016, and they displayed their tail-like structures for up to nine months.

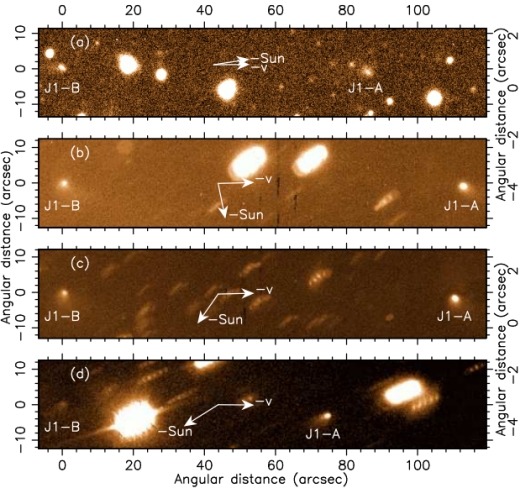

Moreno and team used the Great Telescope of the Canary Islands (GTC) and the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT) to study the P/2016 J1 pair, discovering that the asteroid fragmented about six years ago, based on analysis of its orbital evolution. This makes it the youngest asteroid pair known. The asteroid pair takes 5.65 years to complete an orbit, meaning that the fragmentation would have occurred on the previous orbit.

Image: This is part of Figure 1 from Moreno et al.’s paper on P/2016 J1. Images of P/2016 J1-A and J1-B obtained with MegaCam on the 3.6m CanadaFrance-Hawaii-Telescope on March 17, 2016 (a), and with OSIRIS at the 10.4m Gran Telescopio Canarias on May 15, 2016, May 29, 2016, and July 31, 2016 (b,c,d). In panels (a),(b),(c), and (d), the physical dimensions are 170982×33925, 133788×26545, 135616×26908, and 184964×36699 km, respectively. Credit: Moreno et al.

The tail is not directly caused by the original fragmentation, but seems to have happened as an after-effect. Moreno believes we are looking at dust emissions caused by the sublimation of ice that was originally exposed by the breakup. This contrasts with the earlier asteroid tail on P/2016 G1, which Moreno and colleagues believe was the result of an impact. The team’s models show that the ejected material on P/2016 G1 was not isotropically emitted.

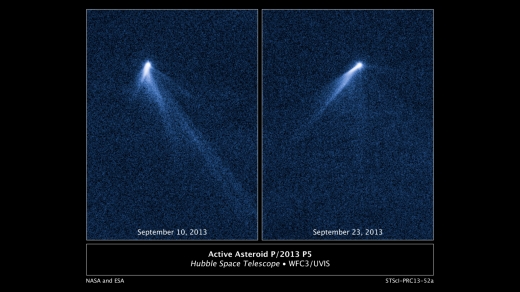

Image: Another view of an activated asteroid with a tail, this one showing Hubble Space Telescope images of the asteroid P/2013P5. Credit: NASA/ESA.

The paper on P/2016 J1 is Moreno et al., “The splitting of double-component active asteroid p/2016 J1 (PANSTARRS),” The Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 837, No. 1 (2017). Abstract / preprint. The paper on P/2016 G1 is Moreno et al., “Early Evolution of Disrupted Asteroid P/2016 G1 (PANSTARRS),” The Astrophysical Journal Letters Vol. 836 No. 2 (2016). Abstract / preprint.

‘Asteroid Hunters’ Look to Defend Earth: Q&A with Author Carrie Nugent

By Sarah Lewin, Staff Writer | March 14, 2017 07:11 am ET

The solar system is much wilder and more chaotic than most people think, and vigilant scientists are all that stand between Earth and a catastrophic asteroid impact, according to a new book on the science of asteroid monitoring and tracking.

“Asteroid Hunters” (Simon & Schuster, 2017), released today (March 14), offers a quick but comprehensive view of what’s happening in Earth’s solar system, and highlights the many eyes on the sky determined to catalog and track every asteroid and near-Earth object that could potentially pose a threat. Plus, it details the different ways we could turn away an unwanted solar system visitor streaming toward Earth.

Space.com talked with “Asteroid Hunters” author Carrie Nugent, a researcher who works with NASA’s asteroid-hunting space telescope NEOWISE (Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer), about the threat of an asteroid impact, how we find them and what we would do if one came knocking.

Full article here:

http://www.space.com/36050-asteroid-hunters-carrie-nugent-interview.html

Could an impact by a planetoid in Earth’s oceans be relatively less devastating than once thought?

http://www.space.com/36451-asteroids-bad-at-making-waves.html

NASA GSFC has come up with an ingenious way to use Lisa Pathfinder to do something it was not originally designed to do… detect comet pieces:

https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2017/nasa-team-explores-using-lisa-pathfinder-as-comet-crumb-detector

Defending Earth against cosmic impacts won’t do any good if we don’t have an excellent detection system in place first:

http://dailycaller.com/2017/05/20/nasa-can-probably-stop-an-asteroid-but-wouldnt-detect-a-comet-in-time-study-finds/

Apophis may not be a threat to Earth in 2029, but a future time is not so certain:

https://phys.org/news/2017-06-impact-threat-asteroid-apophis.html

To quote:

The famous near-Earth asteroid Apophis caused quite a stir in 2004 when it was announced that it could hit our planet. Although the possibility of an impact during its close approach in 2029 was excluded, the asteroid’s collision with Earth in the more distant future cannot be completely ruled out.

“We can rule out a collision at the next closest approach with the Earth, but then the orbit will change in a way that is not fully predictable just now, so we cannot predict the behavior on a longer timescale,” Alberto Cellino of the Observatory of Turin in Italy told Astrowatch.net.

Asteroid Day Turns Informative With UA Panel

OSIRIS-REx team members Daniella DellaGiustina, Heather Enos and Dante Lauretta provide an overview of the mission for a Flandrau audience, and Eric Christensen and Vishnu Reddy also share their insights on asteroids.

By Doug Carroll and Daniel Stolte, University Communications

June 28, 2017

An all-star lineup of University of Arizona space scientists informed and entertained a full house at the Flandrau Science Center & Planetarium on campus, leveraging the occasion of Asteroid Day to demonstrate that there is far more to be learned than feared from extraterrestrial rocks.

Asteroid Day, which is June 30, is an annual global event held on the anniversary of the 1908 Siberian Tunguska explosion classified as the largest impact event in the Earth’s history, widely attributed to an asteroid.

This year, a 24-hour broadcast organized by the nation of Luxembourg will mark the occasion, and a two-hour presentation moderated by television host Geoff Notkin was taped for inclusion Tuesday evening at Flandrau. Local interest was such that overflow space was needed in the adjacent Kuiper Space Sciences building.

“Part of the purpose of Asteroid Day is to raise awareness of the possibility of future impacts,” said Notkin, a meteorite aficionado from the show “Meteorite Men” who lives in Arizona.

Full article here:

https://uanews.arizona.edu/story/asteroid-day-turns-informative-ua-panel

To quote:

A short question-and-answer segment involving the five UA scientists produced some of the evening’s lighter moments.

“My book on how the universe works is so cool that I don’t understand what it says,” one boy said in addressing the panel.

Asked about the impact if Bennu were to hit Earth, Lauretta said it would be about 140 megatons — an impact so great that it “would definitely ruin your day,” he said.