The attitude you bring to a star field changes everything. When I was a kid trying to figure out how to use a small telescope, I scanned the usual suspects — the Moon, Saturn and its rings, the Galilean satellites of Jupiter — all the while planning to branch out into major wonders like M31 or the Ring Nebula in Lyra. But when I turned to deep sky objects, what I discovered was that I could see little more than faint smudges — I was using no more than a 3-inch reflector. It was a disappointment for a while, until I accepted the limitations of my equipment.

And then I became a cataloger of faint smudges, as avidly tracking down celestial objects as any stamp collector sorting through new finds. A patient uncle showed me how to look slightly away from the object I sought, to pick it up in peripheral vision. I began keeping notebooks listing my first glimpses of various nebulae and clusters. So many celestial objects were out of reach, but somehow a field of stars became wondrous not only for what I was seeing but for what I knew I might see with a larger instrument.

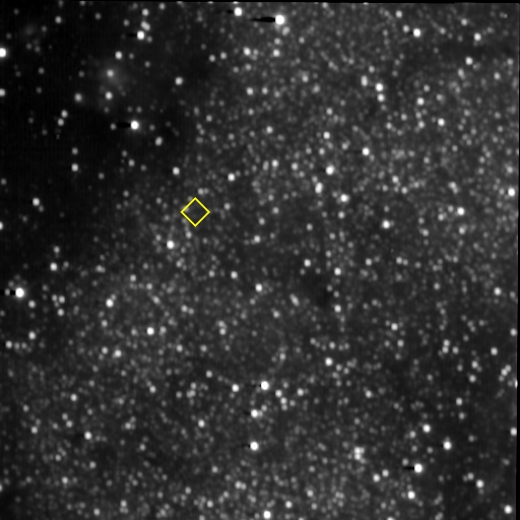

The image below recalled those days precisely because of what we cannot see in it. This is actually drawn from a series of images taken by New Horizons’ LORRI instrument showing the area toward which the craft is heading. We’re looking toward a close approach and flyby of the Kuiper Belt object MU69 at 0200 Eastern US time (0700 UTC) on New Year’s Day of 2019. Right now we’re still far enough way that the target isn’t visible even to LORRI, but to me this image is freighted with the raw excitement of exploration as we push ever deeper into the Solar System.

Image: In preparation for the New Horizons flyby of 2014 MU69 on Jan. 1, 2019, the spacecraft’s Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) took a series of 10-second exposures of the background star field near the location of its target Kuiper Belt object (KBO). This composite image is made from 45 of these 10-second exposures taken on Jan. 28, 2017. The yellow diamond marks the predicted location of MU69 on approach, but the KBO itself was too far from the spacecraft (877 million kilometers) even for LORRI’s telescopic “eye” to detect. New Horizons expects to start seeing MU69 with LORRI in September of 2018 – and the team will use these newly acquired images of the background field to help prepare for that search on approach. Credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute

New Horizons is going into hibernation this week for a 157 day period, and I hadn’t realized until getting this JHU/APL update that the craft had been in full operational mode for almost two and a half years now, which of course dates back to the Pluto encounter and the long period of data return (16 months). Along the way New Horizons has continued to study the dust and charged particle environment of the Kuiper Belt as well as hydrogen in the heliosphere.

We’re now halfway between Pluto and MU69, having reached this point — a distance of 782.45 million kilometers from Pluto and MU69 — early on April 3 (UTC). The gravitational pull of the Sun continues to slow the craft, so it won’t be until tomorrow (April 7) that we reach the halfway point in terms of time between the two close approaches. Remember that New Horizons left Earth orbit traveling faster than any vehicle ever launched, but nine years of climbing out of the gravity well have slowed it to 14 kilometers per second at the Pluto/Charon flyby, significantly below the 17 kilometers per second-plus that Voyager 1 has attained.

The good news is that the mission includes further exploration beyond MU69. Hal Weaver is a New Horizons project scientist from the Applied Physics Laboratory (Laurel, MD):

“The January 2019 MU69 flyby is the next big event for us, but New Horizons is truly a mission to more broadly explore the Kuiper Belt. In addition to MU69, we plan to study more than two-dozen other KBOs in the distance and measure the charged particle and dust environment all the way across the Kuiper Belt.”

Looking ahead once we’re past MU69, there will be so many things we cannot see in the star field ahead. So much to discover for the deep space missions beyond New Horizons. When will a true interstellar probe — a mission designed from the start to examine the local interstellar medium — be launched? Without an answer, we can only keep pushing for exploration, an innate characteristic of our species, and one unlikely to be limited by our Solar System.

Two dozen more KBOs! What does this mean, surely they can’t be hoping to find another fly-by target after MU69?

Jon W.. See the timelines for observation of each KBO.. MU69’s flyby is Jan 1st 2019.. http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/PI-Perspectives/images/2016-12-KBO%20Observation%20Chart%2012-19-16.jpg Enjoy…

I see, thank you! So they are not actual fly-bys, but some of them are relatively close… the closest will be something called 2014OS393 (diameter ~46 km), at just under 0.1 AU or about 9 million miles, at the very end of 2018.

If we did want to launch an interstellar probe using today’s launch technologies, and we aimed for the most favourable set of gravity assists available in the next several years for reaching the interstellar medium asap, not caring about the ultimate direction* of the probe, what kind of speeds could we get it to/how long would it take? I’m wondering if the long wait expected for contact with the interstellar medium is what makes such a mission seem less attractive.

*Actaully, would we want to travel in the direction of the sun’s motion, to exit the heliosphere faster?

I think the response depends on how long you are willing to wait for the interstellar encounter. Voyager, Pioneer and NH are already ‘interstellar probes’ but our species may no longer exist when the encounters happen. I doubt that we could get the requisite speeds by mere gravitational slingshots. Energy required to accelerate 1 kg to 0.1c is 4.5 x 10^15 J (neglecting thermodynamic losses), or approximately 125000 tonnes of TNT.

I meant “interstellar probes” in the sense Paul did in his post: probes of the interstellar medium, not probes of other star systems. Voyager 1 took about 30 years, but of course its mission was optimised for planetary encounters and the interstellar medium is just a bonus. But if you’re shooting for the interstellar medium to begin with, surely you can make use of slingshots to get there quicker even with current launch technology. Can we get there in less than a decade, for example? (New Horizons was launched faster than Voyager, but without as powerful gravitational assists it took 9 years to get to Pluto, about 32 AU away–the heliopause is about 121 AU from the sun)

Any new targets after MU69?

From Emily Lakdawalla’s blog:

“What happens after the flyby? Unfortunately, even if Hubble surveys continued, they would be very unlikely to yield another reachable object after 2014 MU69. The little world is at the edge of the classical Kuiper belt; beyond that, the space around the Sun is far more empty.”

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2015/09011608-new-horizons-extended-mission-pt1.html

Voyager 1 took the Pale Blue Dot shot from 40.5 AU out, according to Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pale_Blue_Dot

They shut down V’ger’s cameras a short time later, essentially permanently.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Voyager_1

New Horizons currently is 38.10 AU from Earth and has somewhere around 5 AU more to go before it reaches MU69. So it looks like it likely will have operational cameras at 40.5 AU out from Earth and beyond.

http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/Mission/Where-is-New-Horizons/index.php

Are they planning to do another one of Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot views back once they reach or exceed 40.5?

And will New Horizons thereafter, as it turns its cameras to MU69 and beyond, be the furthest out operational camera that we’ve had to date?

Peering further out from further out (well, subject to the limits of the instruments in comparison to larger, closer in ones).

I suppose the question is does New Horizons have good an inclination angle on the solar system as Voyager 1 did. Pluto is definitely angled to the ecliptic, but I don’t know if it’s angled enough to make as pretty a shot.

I’ve used Simulation in Astronomy programs… It’s Awesome! You can see the Difference right away… they’re closer together!

I wonder if it would be possible to aim the camera back at the sun and use gravitational lensing to look at another system? Maybe just as a proof of concept?

Interesting thought! but I think we’re not yet into Sol’s focus, which is (I think) out in the Oort cloud. But if the operators try the idea and it works, you deserve credit!

Alas, the focus begins at 550 AU, and I’m not sure where it begins for optical wavelengths. Will need to calculate how long it will be before New Horizons gets out that far!

Paul, this is one my favorite articles of yours. Beautifully written and an exciting topic. Thank you.

My pleasure, Gideon, and thank you. Always glad to have you on the site. And I’m enjoying the recent Twilight Zone material on Galactic Journey. I’ve had a complete run of Twilight Zone on DVD for some time and am finally going through it show by show — just happen to be in Season 3 right now, so your post is quite timely!

Maybe if we located Planet X (or 9 or whatever you want to call it) in time, and we had the immense luck that its orbit was within the reach of the NH with some adjustments of trajectory …

MORE EVIDENCE FOR PLANET NINE: “The curiously warped plane of the Kuiper belt.” by Katheryn Volk, Renu Malhorta. Adding THIS to the mix of ALL THE OTHER CLUES to Planet Nine’s location, my guess is that it will be discovered in LESS THAN A YEAR!

arXiv: 1704.02444

New Horizons PI Alan Stern lets us know what humanity’s fifth interstellar vessel and its mission team will be doing over the next few months as it heads towards its next Kuiper Belt target in 2019:

http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/PI-Perspectives.php?page=piPerspective_04_28_2017

May 25, 2017

New Horizons Deploys Global Team for Rare Look at Next Flyby Target

On New Year’s Day 2019, more than 4 billion miles from home, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft will race past a small Kuiper Belt object known as 2014 MU69 – making this rocky remnant of planetary formation the farthest object ever encountered by any spacecraft.

But over the next six weeks, the New Horizons mission team gets an “MU69” preview of sorts – and a chance to gather some critical encounter-planning information – with a rare look at their target object from Earth.

On June 3, and then again on July 10 and July 17, MU69 will occult – or block the light from – three different stars, one on each date. To observe the June 3 “stellar occultation,” more than 50 team members and collaborators are deploying along projected viewing paths in Argentina and South Africa. They’ll fix camera-equipped portable telescopes on the occultation star and watch for changes in its light that can tell them much about MU69 itself.

“Our primary objective is to determine if there are hazards near MU69 – rings, dust or even satellites – that could affect our flight planning,” said New Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado. “But we also expect to learn more about its orbit and possibly determine its size and shape. All of that will help feed our flyby planning effort.”

Full article here:

http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/News-Center/News-Article.php?page=20170525

New Horizons Team Successfully Observes Transit of Next KBO Target, and Clouds on Pluto!

By Paul Scott Anderson

With the Pluto flyby now well behind them, the New Horizons team has been busy preparing for the next encounter, the small Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) called 2014 MU69. New Horizons is scheduled to fly past 2014 MU69 on Jan. 1, 2019, and it will be the farthest Solar System body to ever be visited so far. From June 2-3, astronomers in Argentina and South Africa pointed their telescopes at 2014 MU69, hoping to catch its “shadow” moving across a background star as it transited the star (also known as a stellar occultation). This would help determine the object’s exact size and allow the mission team to fine-tune the planned flyby. Back at Pluto, there is more evidence, from data gathered by New Horizons during the flyby, for clouds in Pluto’s thin atmosphere.

“The stars aligned for this observing campaign, which was implemented expertly by the team,” said New Horizons Program Executive Adriana Ocampo at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C. “It’s amazing how classical astronomy – from small telescopes to some of the most advanced observatories on Earth – is helping New Horizons plan its next flyby, and it shows how truly global space exploration is.”

The observations went well it seems, according to Principal Investigator Alan Stern, with data collected from all 54 observing teams involved (known as KBO Chasers).

“A tremendous amount had to go right to correctly execute such a massive observation campaign, but it did,” said Principal Investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado. “The main goal of these observations was to search for hazards; the secondary objective was to try to glimpse the occultation of MU69 itself, in order to learn its precise size. Scouring all the dozens of datasets for these two objectives is going to take us a few weeks.”

The success of the observations is due in large part to the Gaia satellite and Hubble Space Telescope. Gaia star positions were combined with Hubble images to provide the information needed to predict the path of MU69’s very narrow shadow across Earth.

“Without Gaia and Hubble, I doubt we could have succeeded so well at this,” Stern said. “Gaia and Hubble were crucial to this success and we thank them both.”

As also noted by Marc Buie, New Horizons SwRI co-investigator, “The Gaia star data has been critical this entire operation. Without it, there was no way we could have predicted such an accurate path.”

There will be two more opportunities this summer to watch stellar occultations by 2014 MU69, on July 10 and 17. NASA’s airborne Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) will also be able to observe the occupation on that day, with no clouds or haze to interfere. Then, on July 17, the New Horizon team will use two dozen small mobile telescopes (each 16 inches/40 centimeters in diameter) in the far southern lands of Patagonia, Argentina to observe the final occultation, but this time using a brighter star in the background. This will make it easier for astronomers to look for evidence of debris around 2014 MU69.

“Our primary objective is to determine if there are hazards near MU69 – rings, dust or even satellites – that could affect our flight planning,” said Stern. “But we also expect to learn more about its orbit and possibly determine its size and shape. All of that will help feed our flyby planning effort.”

“Deploying on two different continents also maximizes our chances of having good weather,” said New Horizons Deputy Project Scientist Cathy Olkin, from SwRI. “The shadow is predicted to go across both locations and we want observers at both, because we wouldn’t want a huge storm system to come through and cloud us out – the event is too important and too fleeting to miss.”

Full article here:

http://www.americaspace.com/2017/06/20/new-horizons-team-successfully-observes-transit-of-next-kbo-target-and-clouds-on-pluto/

To quote:

“The January 2019 MU69 flyby is the next big event for us, but New Horizons is truly a mission to more broadly explore the Kuiper Belt,” said Hal Weaver, New Horizons project scientist from APL, in Laurel, Maryland. “In addition to MU69, we plan to study more than two-dozen other KBOs in the distance and measure the charged particle and dust environment all the way across the Kuiper Belt.”

A blog post from one of the astronomers who participated in the occultation event observations:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2017/20160616-mu69-occulation-campaign.html

To quote:

“What about the results? Did you see the occultation?” you ask. Everyone asks this. Right now, we don’t know yet. This was an extremely challenging occultation to observe. MU69 occulted a very dim star, which always makes the observation tough. On top of that, we need to combine data from 24 deployed sites, plus some fixed sites, that cover a wide range of conditions, including seeing and illumination. Therefore, the data analysis will take awhile.

It is likely that only a couple of the telescopes actually observed the occultation. All of the data, however, will be useful for the New Horizons mission. All of us—astronomers and the general public—just need to wait until the New Horizons team finishes the analysis and announces the results. I am not a New Horizons team member, so I am eagerly awaiting the results like everyone else.