Just how long can a civilization live? It’s a key question, showing up as a factor in the Drake Equation and possibly explaining our lack of success at finding evidence for ETI. But as Andrei Kardashev believed, it is possible that civilizations can live for aeons, curbed only by the resources available to them, opening up the question of how they evolve. In today’s essay, Nick Nielsen looks at long-lived societies, asking whether they would tend toward stasis — Clarke’s The City and the Stars comes to mind — and how the capability of interstellar flight plays into their choices for growth. Would we be aware of them if they were out there? Have a look at supercivilizations, their possible trajectories of development, and consider what such interstellar stagnation might look like to a young and questing species searching for answers.

by J. N. Nielsen

What are stagnant supercivilizations?

As far as I know there are no precise definitions of supercivilizations, but this should not surprise us as there are no precise definitions of civilization simpliciter. In his paper, “On the Inevitability and the Possible Structures of Supercivilizations” (1985), Nikolai S. Kardashev explicitly formulated two assumptions regarding supercivilizations:

“I. The scales of activity of any civilization are restricted only by natural and scientific factors. This assertion implies that all processes observed in Nature (from phenomena in the microcosmos to those in the macrocosmos and all the way to the whole Universe) may in time be utilized by civilizations, be reproduced or even somewhat changed, though of course always in accordance with the laws of Nature.

“II. Civilizations have no inner, inherent limitations on the scales of their activities. This implies that presumptions of a possible self destruction of a civilization, or of a certain restrictions on the level of its development are not factual. Actually social conflicts may in fact be resolved, while civilizations will always face problems that demand larger scales of activity.” [1]

If Kardashev was right, there being only natural and scientific restrictions on the scale of the activity of civilization, and the absence of inherent limitations on civilizations, would mean that an expanding civilization would just keep expanding, subject only to natural laws like those of general relativity and quantum theory, thermodynamics and conservation laws. Presumably, then, older expanding civilizations would eventually become supercivilizations in virtue of the scale of their activities, which would grow proportionally (or perhaps exponentially) to their age. Here we see the relationship between supercivilizations and the recurrent motif of million-year-old or even billion-year-old civilizations. But once grown to these dimensions, what then?

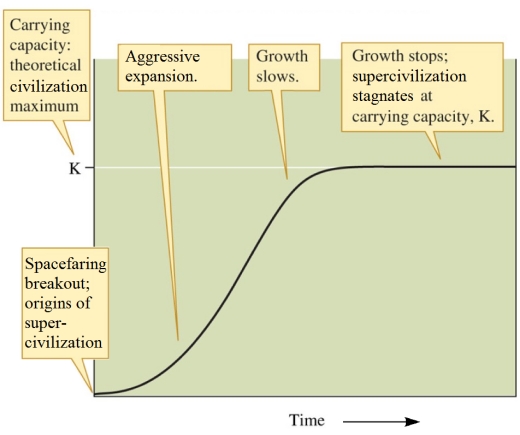

In a series of posts — Stagnant Supercivilizations, An Alternative Formulation of Stagnant Supercivilizations, Suboptimal Civilizations, Supercivilizations and Superstagnation, and What Do Stagnant Supercivilizations Do During Their Million Year Lifespans? — I discussed Kardashevian supercivilizations that have become stagnant—in other words, civilizations that are very old, very large, very powerful, and very advanced, but which have attained a plateau of achievement and thus have ceased to develop. Such civilizations, in a growth phase, may have taken advantage of the absence of any inherent limitation upon the scale of their activities and would have grown to utilize all the processes of nature, subject only to the laws of nature. Their growth trajectory would have described an S-curve, much like a species that converges upon the carrying capacity of its ecosystem. Having reached an equilibrium with its environment—which, in the case of a supercivilization, is the cosmos itself—the growth of a supercivilization would then be limited by galactic ecology. [2]

This seems to contradict Kardashev’s second assumption, that, “Civilizations have no inner, inherent limitations on the scales of their activities,” but the carrying capacity of the cosmos would constitute an extrinsic or exogenous limitation on the scales of a supercivilization’s activities, rather than an intrinsic or endogenous limitation. Moreover, this extrinsic limitation, which, once encountered, entails stagnation, is consistent with Kardashev’s first assumption, that a supercivilization’s activities must be, “in accordance with the laws of Nature” and are restricted by natural factors. The carrying capacity of the cosmos is the natural restriction upon the growth of supercivilizations.

If a galaxy is the ecosystem in which a supercivilization comes to maturity, then the carrying capacity of a galaxy will determine the growth and eventual stagnation of supercivilizations once carrying capacity is reached, with that carrying capacity being determined by the accessibility of available matter and usable energy at the disposal of a supercivilization. This ecological limit to the growth of supercivilizations would constitute, “natural and scientific factors,” that would restrict a supercivilization’s scale of activity, constituting a confirmation of Kardashev’s principles, and would, additionally, make the metaphor of galactic ecology literally true.

This is but one possible scenario for the stagnation of a supercivilization. Sagan and Newman suggested a scenario of supercivilization stagnation based upon the intelligent progenitor species of a civilization transcending their biological limitations and becoming effectively immortal:

“A society of immortals must practice more stringent population control than a society of mortals. In addition, whatever its other charms, interstellar spaceflight must pose more serious hazards than residence on the home planet. To the extent that such predispositions are inherited, natural selection would tend in such a world to eliminate those individuals lacking a deep passion for the longest possible lifespans, assuming no initial differential replication.” [3]

According to Sagan and Newman the result of this would be:

“…a civilization with a profound commitment to stasis even on rather long cosmic time scales and a predisposition antithetical to interstellar colonization.” [4]

I could criticize this scenario on several grounds, but my purpose here is not to engage with the argument, but to present it for exhibition as one among multiple possible sources of stagnation for advanced civilizations. The point is that even the largest, oldest, most advanced civilizations are subject to stagnation—perhaps especially subject to stagnation.

[We could pursue terraforming within our own planetary system even without interstellar travel.]

Are there hard limits to interstellar travel?

In the argument that I unfolded in What Do Stagnant Supercivilizations Do During Their Million Year Lifespans? so as to concede a point to potential critics before this was used as a cudgel against my argument, I tried to show how, even without interstellar travel, a supercivilization could provide for itself civilizational-scale stimulation. My argument was that even a supercivilization confined to its home planetary system could engage in terraforming (or its non-terrestrial equivalent) and even world-building, and so might be able to observe the development of life over biological scales of time and the development of intelligence and civilization over their respective scales of time.

My assumption in making this argument was that a civilization in a position to make scientific observations of phenomena as fundamental as the origins of life, intelligence, and civilization, eventually would formulate a vast body of scientific knowledge based on these scientific observations. All of this was mere prelude in order to ask the question that was bothering me at the time: could a supercivilization remain stagnant when it was in a position to assimilate a vast body of scientific knowledge? It seems unlikely to me that a civilization that had grown to supercivilization status in virtue of its mastery of science and technology could remain unaffected by an influx of scientific knowledge.

As I noted above, I sought to demonstrate the possibility of civilizational-scale intellectual stimulation without recourse to interstellar space travel in order to focus on what is still possible to a very old civilization even under hard limits to space travel. If such a civilization also possessed technology sufficient for interstellar travel, then the possibilities for stimulation would be all the greater, and my argument would be strengthened, so that considering the narrower question of a supercivilization stranded within its home planetary system constituted a more rigorous test of the idea of civilizational-scale scientific stimulation.

We all know that, even among scientists, even among advocates of space travel, there are those who insist upon hard limits to interstellar travel. Hence the need to make an argument without an appeal to interstellar travel. This insistence upon hard limits to interstellar travel is not my position, but I do want to try to understand the reasoning and the motivations that have led otherwise intelligent individuals to declare interstellar travel to be not merely difficult, but an insuperable impossibility (or so difficult as to be impossible for all practical purposes). What, then, are the reasons given for the impossibility or impracticality of interstellar travel? I will consider this question by way of a digression discussing the idea of the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) and what I call the SETI paradigm.

[The SETI paradigm incorporates assumptions about the likelihood of interstellar travel.]

What is the SETI Paradigm?

Among those who insist upon hard limits to interstellar travel are many advocates of SETI, which is usually conceived as searching for intelligent extraterrestrial signals, whether radio or optical or otherwise. The two positions—denial of the possibility of interstellar travel and pursuit of SETI—are tightly-coupled, as the unlikelihood of interstellar spacefaring civilization is used to argue for SETI as the only alternative to discovering other life and intelligence in the universe through space exploration.

Philip Morrison, who along with Giuseppe Cocconi wrote the first paper on the possibility of SETI, also held this view in regard to, “…real interstellar travel, where people, intelligent machines, or whatever you like, go out to colonize. You travel in space as Magellan circumnavigated the world. I do not think this will ever happen. It is very difficult to travel in space.” [5]

Perhaps the locus classicus of the SETI paradigm was to be found already in 1962, three years after the Cocconi and Morrison paper:

“…space travel, even in the most distant future, will be confined completely to our own planetary system, and a similar conclusion will hold for any other civilization, no matter how advanced it may be. The only means of communication between different civilizations thus seems to be electro-magnetic signals.” [6]

And here is another clear statement of the SETI paradigm:

“The bottom line of all this is quite simply that interstellar travel is so enormously expensive and/or perhaps hazardous, that advanced civilizations do not engage in the practice because of the ease of information transfer via interstellar communication links.” [7]

The frequency with which cautions regarding the danger of interstellar travel are employed as an argument against interstellar travel suggests that the class of persons writing against interstellar travel are risk averse, but that does not mean that all sectors of society are equally risk averse. Some individuals seek out risk in order to confront “limit-experiences” (expérience limite), and never feel so fully as alive as when facing danger, death, and the possibility of personal annihilation. [8]

If we set aside the danger of interstellar travel as an artifact of risk aversion, knowing that risk tolerance is one of those individual variations that drives natural selection, we are left with the argument that interstellar spaceflight would be too expensive and too difficult to pursue. The potential cost of interstellar travel is a matter for another essay on another occasion, but I will only observe here that we do not yet know the economics of supercivilizations, so we must keep an open mind as to whether or not interstellar missions would be prohibitively expensive. I do not think that interstellar travel would be too expensive because a fully automated space-based industrial infrastructure, in possession of the energy and materials that are available beyond planetary surfaces, would find few construction projects to be too expensive, as there would be no economic trade-offs between building starships and producing consumer goods.

The idea that interstellar travel is enormously difficult I do not dispute, though I find it strange that anyone would argue for the, “…ease of information transfer via interstellar communication links,” when these links could not facilitate communication over scales of time relevant to civilization, except for communication with the nearest stars. If there were advanced civilizations located at the nearest stars, with which we might communicate over a time scale of years or even decades, we would already know about these cosmic neighbors. If there are advanced civilizations, then, they must be distant from us, and the greater the distance from us, the more unrealistic it is to imagine that civilizations could communicate on a civilizational scale of time.

I find it astonishing that those coming from the perspective of the SETI paradigm (which assumes limits on interstellar travel, whether hard or relatively soft limits) imagine an advanced civilization having the patience to wait thousands or tens of thousands of years for a message exchange, but being unwilling to send out interstellar missions operating on a similar scale of time. Here we must imagine supercivilizations who do not have the patience to develop advanced transportation technologies, but which do have the patience to wait thousands of years, or tens of thousands of years, or hundreds of thousands of years, to exchange messages with another civilization. For a stagnant supercivilization, this is easily imaginable and possible, but for a civilization in its growth phase, on the path to attaining supercivilization status, a thousand years of technological development is many times longer than terrestrial technological development since the industrial revolution, which has taken us from sailing ship to spaceship.

If a civilization were to send out a message, then collapse some thousands of years later, and the response to the message were then to arrive for some successor civilization still more millennia later, this could be not considered a conversation among civilizations. Under these conditions, only one-way messages make any sense. However, if relativistic spaceflight were to be developed, the intelligent progenitors of a civilization could travel directly to other civilizations and converse with them face-to-face (if both parties to the conversation possessed faces, that is). Now, it is true that civilization on the homeworld of this intelligent progenitor species would experience the same time lapse as beings who stayed on their homeworld and attempted to communicate by conventional SETI means, but those who actually traveled and experienced time dilation could directly experience all that there is to be experienced in the universe. A species in possession of relativistic spaceflight could always arrange for rendezvous with similarly time dilated communities to which they could return. Such a civilization would be “temporally distributed.” This is the argument I attempted to make, however imperfectly, in my previous Centauri Dreams post, Stepping Stones Across the Cosmos, though I suppose I didn’t explain myself adequately.

It beggars belief to suppose that a civilization in possession of relativistic spaceflight would choose to remain on its homeworld, waiting for signals thousands or millions of years old, when it could go out into the cosmos and investigate matters firsthand and to engage with the intelligent progenitors of other civilizations (if there are such) as peers, i.e., as fellow beings. I do not say that it is impossible that this should be the case, but it strikes me as extremely unlikely. If human civilization came into possession of relativistic spaceflight technology, and only one percent of the present human population of (more than) seven billion were interested in this development, there would still be seventy million human beings exploring the universe, and arranging rendezvous with groups having experienced similar time dilation and so belonging to the same historical period (and thus having something in common).

It is not uncommon, however, to view SETI not as predicated upon the impossibility of interstellar flight, and therefore as a substitute for direct contact, but rather as what we can do right now to establish contact, with interstellar travel still in the offing, yet to play its role when our technology achieves that level of development. In this sense, the SETI paradigm and actual exploration are in no sense inherently in conflict. It is entirely possible that a spacefaring civilization might possess a capability to explore relatively nearby planetary systems and yet eventually find itself at a very great distance from any other civilization, with which it could only communicate by electromagnetic means. Both of these enterprises—exploring nearby planetary systems, even if they have no life and no civilization, and communicating with other civilizations too distant for direct travel—would be profoundly stimulating to a civilization in scientific terms. Nevertheless, the SETI paradigm remains a powerful point of reference because in internal coherency of the assumptions it makes.

The advocate of the SETI paradigm must assert that interstellar travel is impossible, because, if it is possible, the idea of a grand Encyclopedia Galactica existing in the form of a network of SETI signals crisscrossing the cosmos is very unlikely to be realized. Thus this cluster of assumptions that I call the SETI paradigm —that interstellar travel is difficult or impossible, that communication is easy, and therefore SETI and METI are, or ought to be, the focus of the efforts of advanced civilizations to interact with peers—hang together by mutual implication. If we reject any one aspect of the paradigm, it falls apart. [9] The SETI enterprise may remain, but it becomes a small part of a big picture, and is no longer the big picture itself.

[Are we confined to our oasis in space?]

Is planetary endemism the eternal truth of humanity?

For some scientists, not directly concerned with SETI as an alternative for exploration, expressing the difficulty of interstellar travel and the unlikelihood of human beings traveling to other worlds has been a way to express the spirit of seriousness (yes, I am invoking Sartre [10]) in relationship to human planetary endemism, since the prior seriousness of our cosmological disposition (our Ptolemaic centrality) was deprived us by the Copernican revolution. No longer at the center of the universe, and schooled in humility by hundreds of years of Copernicanism, we have become acculturated to our apparently marginal role in the universe, and one way to express this idea is to assert that our marginal status is bound to our marginal homeworld orbiting a marginal star in a marginal galaxy.

Given this acculturation, our attachment to our homeworld—rather than being a mere empirical contingency, a truth ready-made by the accident of our origin upon a planetary body—is, as Sartre said, “…an ethics which is ashamed of itself and does not dare speak its name.” Instead of saying (though some do say this), “We ought not to leave Earth,” the SETI paradigm tells us, “We cannot leave Earth.” (The “ought” has been transformed into an “is”; it is brute fact, and no longer subject to volition.) And if we cannot leave Earth, our special relationship to Earth is retained. What Copernicanism has taken from us with one hand, it gives back with the other. We once again have a “special” relationship to Earth, though not the special relationship posited by the Ptolemaic system and its Aristotelian embroiderings.

For example, in my earlier Centauri Dreams post How We Get There Matters I quoted this from Peter Ward and Donald Brownlee:

“The starships of TV, movies, and novels are products of wishful thinking. Interstellar travel will likely never happen, meaning we are stranded in this solar system forever. We are also likely to be permanently stuck on Earth. It is our oasis in space, and the present is our very special place in time. Humans should enjoy and cherish their day in the Sun on a very special planet and not dwell too seriously on thoughts of unicorns, minotaurs, mermaids, or the Starship Enterprise. Our experience on Earth is probably repeated endlessly in the cosmos. Life develops on planets but it is ultimately destroyed by the light of a slowly brightening star. It is a cruel fact of nature that life-giving stars always go bad.” [11]

Eminent entomologist E. O. Wilson [12] went even farther than Ward and Brownlee:

“Another principle that I believe can be justified by scientific evidence so far is that nobody is going to emigrate from this planet, not ever.” [13]

Note that these are assertions without argument, though they invoke scientific evidence without actually arguing from scientific evidence. (I am going to quote more of the latter passage in another post to come, as it perfectly exemplifies a particular perspective on the human condition.)

These extrapolations beyond the SETI paradigm are arguably more damaging than the SETI paradigm itself, because it raises planetary endemism to a metaphysical status, seeking to overturn the essence of the Copernican revolution. The original formulations of the SETI paradigm were made by scientists who had clear and unambiguous reasons for favoring SETI communication over actual exploration, but those who have taken up the SETI paradigm as a way to express their skepticism about a spacefaring future have no such reasons, or, if they have them, they do not state them.

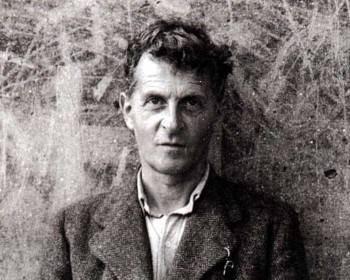

[Ludwig Wittgenstein]

Are we dealing with implicit proscriptions?

It could be that those who argue for hard limits to interstellar travel are incorporating implicit boundaries to the discussion, which, not having been made explicit, have not been part of the argument. This is particularly true in relation to a discussion of supercivilizations, which I will try to show below.

Wittgenstein noted such implicit proscriptions in a passage from his Philosophical Investigations:

“Someone says to me, ‘Show the children a game.’ I teach them gambling with dice, and the other says, ‘I didn’t mean that sort of game.’ In that case, must he have had the exclusion of the game with dice before his mind when he gave me the order?” [14]

This is how people most often talk at cross-purposes, and so we must make an effort to bring such presuppositions to the surface and make them explicit. What I particularly have in mind in regard to implicit boundaries to the scope of a discussion is the possibility that when someone says, “Interstellar travel is impossible,” what they really mean to say is that, “Interstellar travel is impossible within a given time horizon,” or, “Interstellar travel is impossible based on known science and technology.” This is of interest to me in the present context because the longevity of a supercivilization would presumably exceed the bounds of some ordinarily assumed time horizon, so that while most discussion of civilization would not need to address interstellar travel, it might still be allowed that interstellar travel is possible for supercivilizations, and ought to be discussed in relation to them.

Some of the quotes above seem to clearly rule out implicit qualifications to the assertions being made. For example, the quote from Sebastian von Hoerner explicitly stipulates that, “…space travel, even in the most distant future, will be confined completely to our own planetary system, and a similar conclusion will hold for any other civilization, no matter how advanced it may be.” [emphasis added] This doesn’t seem to leave much room for ambiguity. We need to take von Hoerner at his word, and see what it would mean for a civilization to be incapable of interstellar travel regardless of its age or its technological achievements, regardless of where it finds itself in the universe or in the history of the cosmos.

Without making any implicit boundaries of a discussion explicit, the denial of the possibility of interstellar travel becomes the denial of the possibility of interstellar travel by any civilization (1), at any stage of development (2), at any time in the history of the universe (3), by any means (4), and at any location within the universe (5). This would be a very strong assertion to make, and I can’t imagine that many would agree to it if they fully understood that which they were implicitly asserting. [15]

We could take these five implied conditions in turn and formulate how these implicit qualifications to the denial of the possibility of interstellar travel might be formulated if made explicit:

1. Yes, interstellar travel is impossible for our civilization, but not necessarily for some other kind of civilization, and not necessarily impossible for a supercivilization.

2. Yes, interstellar travel is impossible for our civilization at its present stage of development, but given a sufficiently long-lived civilization interstellar travel might be possible.

3. Yes, interstellar travel is impossible at the present time in the history of the universe, but it may be possible at some other time when, for instance, another star approaches the sun closely enough for us to travel to it. [16]

4. Yes, interstellar travel is impossible for known technologies, but we may yet develop technologies that will make it possible, or these technologies may be developed by other kinds civilizations.

5. Yes, interstellar travel is impossible for us, located in a diffusely populated arm of our spiral galaxy, but it might be possible for civilizations located in regions of the galaxy where stars are more closely spaced (such as galactic centers, globular clusters, or merely closely-packed regions of elliptical galaxies).

When we put together the possibilities of different kinds of civilizations (including the different kind of civilization our civilization may become in the future), at different stages of development, at different times in the natural history of the universe, involving different means of transportation, and in other parts of the universe when stars are not as diffusely distributed, it seems a bit contrarian (and I don’t mean that in a flattering way) to insist that any and all interstellar travel is impossible.

A further implicit qualification may be present. Disavowals of the possibility of interstellar travel might be interpreted as specifically addressing the known cosmological circumstances for terrestrial civilization only, or such might be more widely interpreted as holding for any civilization that shares Earth’s cosmological circumstances, or, more widely yet, may hold for civilization whatsoever. In the narrowest of these three senses, the implicit qualification may be made explicit by asserting the proviso, “Well, yes, interstellar travel might be possible under these circumstances, addressing the above qualifications as we have done, but since we are likely the only civilization in the galaxy, the particular cosmological circumstances of Earth and terrestrial civilization are the only cosmological circumstances that really count. A civilization located in a globular cluster where stars are less than a light year apart might be able to pursue interstellar travel, but there are no civilizations; this class of civilizations is the empty set, so we may set it aside.”

By this same reasoning, any consideration of what supercivilizations might accomplish can also be set aside, because terrestrial civilization is not a supercivilization, and if we limit ourselves to what terrestrial civilization is now, and what it can do now, where it is located now, and so on, then we can dismiss the possibility of interstellar travel. (We can also dismiss any future for ourselves other than an eternally-iterated present.) Moreover, we have no particular reason to believe that terrestrial civilization will become a supercivilization, even if it survives for thousands of years or more. Whether or not a civilization does or can develop into a supercivilization may be entirely a matter of mere historical contingency, and, in this sense, the particular cosmological circumstances of Earth will mean the difference between whether terrestrial civilization can develop into a supercivilization, or if it will inevitably fail to do so. Moreover, whether or not a supercivilization stagnates or continues to develop may also be entirely a matter of mere historical contingency (an artifact of galactic endemism, as it were).

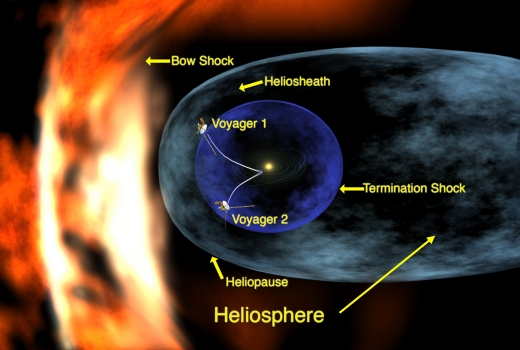

[“…we have all entered the Interstellar Age.” Jim Bell]

Is interstellar travel inevitable for long-lived civilizations?

When we combine technologies already known to us, despite our rudimentary development as a technological civilization, and the changing circumstances of the galaxies, which will, over a cosmological scale of time, move some stars closer to us (as other stars move farther from us), denying the possibility of eventual interstellar travel is like denying the possibility of what is already known. It is arguable, then, that interstellar travel is inevitable for supercivilizations. If a civilization persists for a period of time sufficient to become a supercivilization, it would persist through additional stages of development, through changing distances among stars, and through changing cosmological conditions, so that a settled and deliberate avoidance of interstellar travel would seem to be a precondition of a very old and advanced civilizations that never achieved interstellar breakout. We cannot rule this out, but we also cannot assume that every civilization will cultivate a settled and deliberate avoidance of space travel.

We are already capable of sending out a spacecraft into interstellar space. The “grand tour” gravitational assist of the Voyager probes has already sent Voyager 1 outside the solar system, though that was not part of the original mission of that spacecraft, and the spacecraft is not on a trajectory specifically tailored to encounter another star (though it may pass near another star over sufficiently long scales of time). But Voyager is in interstellar space, and in virtue of this Jim Bell has asserted, “…now the Voyagers are leaving the protective bubble of our sun and crossing over into the uncharted territory between the stars… we have all entered the Interstellar Age.” [17] By this measure, terrestrial civilization has already achieved interstellar breakout.

The gravitational assist that has been extensively employed to send robotic probes throughout our solar system, if specifically tailored to interstellar purposes, could significantly improve on Voyager’s trajectory in terms of getting a spacecraft to another planetary system. Given the possibility of an interstellar gravitational assist (cf. The Interstellar Gravitational Assist by Paul Gilster), and the possibility of selecting a trajectory specifically for the purpose to traveling to a star brought relatively nearby to us (i.e., optimizing the gravitational assist for an interstellar trajectory), even if terrestrial civilization stagnated at or near its present technological level of development, it would still be capable of interstellar travel if it endures for a sufficient period of time.

Similar considerations hold civilizations that happen to find themselves in cosmological circumstances more amenable to interstellar travel. In their paper “Globular Clusters as Cradles of Life and Advanced Civilizations” (which I discussed in The Globular Cluster Opportunity), R. Di Stefano and A. Ray discuss the possibilities for advanced spacefaring civilizations in globular clusters, where stars are more closely distributed and travel times between stars and their planetary systems would therefore be shorter than travel times among stars as we typically find them distributed in the arms of spiral galaxies. [18]

[“Assembling a Space Station” by Klaus Bürgle]

Would we recognize another stagnant supercivilization as a peer?

Even without “breakthrough” technologies, utilizing the science and technology available to a civilization a couple of hundred years into its industrial revolution, interstellar flight is conceivable, and, under some circumstances, practicable. Unique cosmological circumstances in which relatively low technological interstellar travel is possible may serve as incubators for spacefaring civilizations, which, under this unique selection pressure, would be more likely to develop the sciences and technologies conducive to the expansion of spacefaring civilization, and which would definitely lead to the development of the practical engineering skills necessary to (even nearby) interstellar travel.

Such a civilization would have far more practical engineering experience in spacecraft and living in space than we possess, even if it did not possess any science or technology that we do not also possess. To a certain degree (though not to an absolute degree), engineering expertise can vary independently of scientific knowledge and technological development. (Technologies have often grown out of engineering experience, so that technology and engineering tend to be more tightly-coupled than science and engineering.) We are reminded of this when we consider the lithic technology of Pleistocene human beings, or the stone-working technologies of early civilizations and their monumental architecture, the particular engineering techniques of which have been lost, and which are thus mysterious to us. Analogously, a spacefaring civilization with greater engineering experience in space than contemporary terrestrial civilization, but no greater scientific knowledge, initially might appear mysterious to us.

A truly ambitious civilization of this kind, perhaps not greatly technologically advanced, but with a determination to project itself into the cosmos, could, over cosmological scales of time (if it could survive that long), pass from one planetary system to another as stars passed nearby each other, pursuing a strategy of opportunistic interstellar travel, hopping from one nearly planetary system to the next, as the occasion presented itself. Such a civilization need not be advanced much beyond the level contemplated by Wernher von Braun in his mid-twentieth century plans for a space program that could ultimately, “…build a bridge to the stars, so that when the Sun dies, humanity will not die.” [19] A rudimentary spacefaring civilization of this kind could, over millions of years, expand throughout a significant portion of the galaxy. They might even be so “quiet” in electromagnetic terms, and leave such a light footprint on the galaxy, that we do not see them coming.

It would be a shock for us on Earth if we were eventually “discovered” by some civilization less technologically advanced than we are, but more keen on space exploration, and willing to invest blood and treasure in the effort when terrestrial civilization is not yet willing to invest in the enterprise. For if terrestrial civilization endures to become a supercivilization, but remains tightly-coupled to its homeworld, fearful to extend its reach into the cosmos, we are likely to be “discovered” rather than being the ones to do the discovering. Carl Sagan once wrote, “The surface of the Earth is the shore of the cosmic ocean… Recently, we have waded a little out to sea, enough to dampen our toes or, at most, wet our ankles. The water seems inviting. The ocean calls.” [20] Though the ocean calls, we have hesitated on the shore. Given a sufficiently long period of time—a scale of time over which a supercivilization might endure—there may be other civilizations that do not hesitate.

In my last Centuari Dreams post, Synchrony in Outer Space, I argued that civilizations can retrench from development that becomes so rapid as to be disorienting and socially disruptive, and that this may have happened with the mid-twentieth century space program, which was defunded and neglected after the Apollo Program, but which could have been expanded, had the political will been present (cf. Late-Adopter Spacefaring Civilization: the Preemption that Didn’t Happen). In the event of a (counterfactual) expansion of the mid-twentieth century space program, the history of terrestrial civilization would have bifurcated sharply from the path it did in fact take.

If we encountered a civilization that had taken an earlier path to spacefaring civilization, would we recognize them as the path not taken by terrestrial civilization, as being, in a sense, a peer civilization? This would be the meeting of two different kinds of stagnant supercivilizations—one that stagnated scientifically, but which expanded beyond its homeworld, and another that continued to expand the frontiers of scientific knowledge, but which stagnated on its homeworld—neither of them the kind of supercivilization that runs into the limit of the carrying capacity of the galaxy, and neither of them in possession of relativistic spaceflight technology.

These two civiilzations, supercivilizations in virtue of having endured for cosmologically significant periods of time, might be identified as instances of partially stagnant civilizations, and, in this sense, suboptimal civilizations (more specifically, suboptimal supercivilizations). If we acknowledge the possibility of suboptimal partially stagnant civilizations, we would not be surprised that such civilizations had not exhaustively colonized the entire galaxy, and that they had not built a powerful SETI beacon. Many such civilizations might be simultaneously present in the galaxy and yet know nothing of each other. This could be called the “suboptimal hypothesis” in response to the Fermi paradox.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

Notes

[1] “On the Inevitability and the Possible Structures of Supercivilizations,” Nikolai S. Kardashev, in M. D. Papagiannis (ed.), The Search for Extraterrestrial Life: Recent Developments, Proceedings of the 112th Symposium of the International Astronomical Union Held at Boston University, Boston, Mass., U.S.A., June 18-21, 1984, Springer, 1985, 497-504.

[2] Galactic ecology has been characterized thus: “The timescale for the Galactic ecology is determined by the rate of star formation and the lifetime of the most massive stars (a few million years). This ecology must have existed, though in gradually changing form, over the life of the Galaxy. It is driven by the energy flows from the massive stars, and the material cycle through these same stars. Carbon, and heavier elements, are created in the massive stars, and released through winds and supernova explosions. They cycle between the various phases of the interstellar medium, before again being incorporated into stars and, in some cases, planetary systems and life. Further star formation in a molecular cloud is self-regulated by the massive stars already forming, and by the cooling agents which are already present in it. These agents gradually change as the elemental abundances, particularly of carbon, increase as the Galaxy evolves.” Michael G Burton, “Ecosystems, from life, to the Earth, to the Galaxy” (2001)

[3] “Galactic Civilizations: Population Dynamics and Interstellar Diffusion,” William I. Newman, Carl Sagan, ICARUS 46, 293-327, 1981, p. 295.

[4] Loc. cit.

[5] Morrison, Philip, “Conclusion: Entropy, Life, and Communication,” in Ponnamperuma, Cyril, and Cameron, A.G.W., Interstellar Communication: Scientific Perspectives, Boston, et al.: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1974, p. 171.

[6] von Hoerner, Sebastian, “The General Limits of Space Travel,” Science, 06 Jul 1962: Vol. 137, Issue 3523, pp. 18-23, DOI: 10.1126/science.137.3523.18)

[7] Wolfe, John H., “On the Question of Interstellar Travel,” in The Search for Extraterrestrial Life: Recent Developments, edited by Papagiannis, Michael D., Dordrecht: D. Reidel Publishing Company, 1985, pp. 449-454)

[8] Of limit-experiences Michel Foucault wrote, “…the point of life which lies as close as possible to the impossibility of living, which lies at the limit or the extreme.” Foucault, Remarks on Marx, semiotext(e), 1991, p. 31. In relation to John Rawls’ famous thought experiment characterizing a just society as one in which the society is constituted from behind a veil of ignorance as to our place in that society, it has been pointed out that the implied risk aversion is in no sense universal, and there are many who might favor a less “just” society on the premise that an able individual not opposed to risk-taking may make a better place for himself in such a world through his own effort.

[9] In calling this the “SETI paradigm” I do not mean to imply that everyone engaged in SETI accepts this paradigm, nor do I wish to argue against the legitimacy or indeed the importance of SETI, which I view as a worthwhile endeavor.

[10] Of the spirit of seriousness Sartre wrote, “The spirit of seriousness has two characteristics: it considers values as transcendent givens independent of human subjectivity, and it transfers the quality of ‘desirable’ from the ontological structure of things to their simple material constitution. For the spirit of seriousness, for example, bread is desirable because it is necessary to live (a value written in an intelligible heaven) and because bread is nourishing. The result of the serious attitude, which as we know rules the world, is to cause the symbolic values of things to be drunk in by their empirical idiosyncrasy as ink by a blotter; it puts forward the opacity of the desired object and posits it in itself as a desirable irreducible. Thus we are already on the moral plane but concurrently on that of bad faith, for it is an ethics which is ashamed of itself and does not dare speak its name. It has obscured all its goals in order to free itself from anguish. Man pursues being blindly by hiding from himself the free project which is this pursuit.” Sartre, Jean-Paul, Being and Nothingness, New York: Washington Square Press, 1969, p. 796.

[11] Peter Ward and Donald Brownlee, The Life and Death of Planet Earth: How the New Science of Astrobiology Charts the Ultimate Fate of Our World, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2002, pp. 207-208.

[12] Of Wilson I recently noted, “…the major ideas that have marked his scientific career — island biogeography, sociobiology (which turned out to be evolutionary psychology in its nascent state), biophilia, multi-level selection, of which one component is group selection, and the recognition of eusociality as a distinct form of emergent complexity—are ideas that I have used repeatedly in the exposition of my own thought.” I repeat this here so that the reader understands that I in no sense impugn the scientific work of Wilson.

[13] E. O. Wilson, The Social Conquest of Earth, Part VI, chapter 27.

[14] Wittgenstein, Ludwig, Philosophical Investigations, Macmillan, 1989, between sections 70 and 71. This remark is not included in all editions of the Philosophical Investigations, e.g., it does not appear in the 50th anniversary commemorative edition.

[15] The argument I am employing here closely parallels the argument that G. E. Moore makes against unqualified formulations of utilitarianism in his short book Ethics. It is interesting to note in the present context that Moore’s argument against utilitarian takes as a counterfactual unanticipated by unqualified formulations of utilitarianism the possibility of extraterrestrial beings who would not respond to pleasure and pain as do human beings.

[16] Gliese 710 is likely to pass close to our solar system 1.35 million years from now, by which time, if terrestrial civilization survives, it will be a million-year-old supercivilization. In the recent paper “Searching for Stars Closely Encountering with the Solar System Based on Data from the Gaia DR1 and RAVE5 Catalogues,” by V.V. Bobylev and A.T. Bajkova, the authors review stars that will pass within one parsec of our solar system (less than the current distance to Proxima Centauri).

[17] Bell, Jim, The Interstellar Age: Inside the Forty-Year Voyager Mission, New York: Dutton, 2015, p. 3.

[18] Farther yet in the future, after the Milky Way and Andromeda galaxies have merged, and the stars of these galaxies will have been significantly rearranged, so to speak, our sun will have run its race, but many stars that are relatively isolated in regard to their stellar neighborhood may find themselves suddenly (on a cosmological scale of time) with a close neighbor, and vice versa. In this way, the cosmological context of any given planetary system might be radically altered over time.

[19] Quoted in Bob Ward, Dr. Space: The Life of Wernher von Braun, Annapolis, US: Naval Institute Press, 2013, Chapter 22, p. 218, with a footnote giving as the source, “Transcript, NBC’s Today program, New York, November 11, 1998.”

[20] Carl Sagan, Cosmos, chapter 1.

I think than ansibles neutrino comm tech might be a spaceflight killer.

You get that too quickly–and the space launch industry fsalls out with no more com-sat industry to prop it up.

And no broadcasting with RF makes for a quiet universe.

That’s your Fermi paradox, explained in a nutshell.

Communication through quantum entanglement (which is what I understand by Le Guin’s “ansible”) as we understand it at the present time is limited to communication between originally entangled particles that have later been separated. So you still need actual physical space flight to separate them to cosmological distances. Now, there is physics we don’t know yet, and this may change the possibilities for communication. However, this would involve science and technology beyond the level of contemporary terrestrial civilization, and beyond our immediate ability to forecast near-term developments in science and technology. Given this qualification, it does not address my example of a civilization that stagnates scientifically but expands cosmologically.

Best wishes,

Nick

Le Guin’s “ansible” must use something else than quantum entanglement. FTL communication is not a consequence of entanglement.

See No-communication theorem in Wikipedia.

Also

Lectures on Quantum Mechanics 2nd Edition, Steven Weinberg. 2015.

Right, took me a long, long time to understand that, because all the popularized accounts of the experiments, aimed at laymen, are simplified in exactly such a way as to conceal this. They always omit the little details that make this clear.

I’ve come to really loathe popularized accounts of science, for just that reason.

Thanks for the references.

One trait that appears to be universal to all of the advocates to “staying home” on Earth, such as E.O. Wilson and Kim Stanley Robinson, is an implacable hostility towards pioneering of the Jackson/Heinlein context. I believe this motivation serves as the basis of their opinions on this matter.

It would be worthwhile to analyze the ideologies involved in “staying home” vs. cosmic expansion, which would be an analysis of nascent ideologies not yet fully formed. If a civilization launches itself upon exploratory journeys in the cosmos, these experiences are likely to profoundly affect the moral and intellectual development of intelligent progenitor species involved in the exploration and expansion, so that the ideologies that inspired these efforts would be changed by their implementation.

It is difficult for me personally to understand the hostility that you mention, though I have encountered it, so I know it’s a common view and I would like to be able to understand it. It is not clear to me if this is a temperamental expression of individual variability (and therefore ultimately biological in origin, which in this instance means an expression of our evolutionary psychology) or if it is more cultural and due to particular features of education, acculturation, and the peculiarities of the present stage of the development of our civilization. Nature vs. nurture. I guess it’s probably both.

Sincerely,

Nick

As an American, I can only talk about the situation in the U.S. There are two major political factions, the liberal-left and the alt-right, that are “illiberal” in the John Locke classical liberal sense. Of the two, the liberal-left is entirely inimical to pioneering and autonomy by self-interested groups. This view is summed up in the recent Kim Stanley Robinson novels. The alt-right, on the other hand, is not necessarily hostile to pioneering per se. But much of their writings is couched in a semi-feudal terms in a manner that they seem to glorify the medieval period in Europe, which was certainly not about pioneering at all. More specifically, they express hostility towards Lockean classical liberalism, which I consider to be the philosophical root of pioneering in the Jackson/Heinleinien context.

I have visited various European countries on business. But I lived in various East Asian countries for 10 years. I can tell you that nearly every European I met does not have a pioneering bone in their body. Its as though they are culturally and even genetically hostile to pioneering in any form.

The East Asian people, particularly the Chinese, are the consummate traders of the world (e.g. Overseas Chinese of SE Asia). The Japanese and Koreans much less so. However, these people as well do not have a pioneering bone in their bodies either (as my Japanese wife will freely admit).

Pioneering appears to be an Anglo-American thing, if not exclusively American.

‘I can tell you that nearly every European I met does not have a pioneering bone in their body. Its as though they are culturally and even genetically hostile to pioneering in any form.’

They may have learned that pioneering in someone else’s yard leads to trouble and so avoid it.

Given that Europeans of most countries established the USA, I find it hard to believe that there is not a fraction of Europeans that wouldn’t pioneer if given the right opportunity. Currently, there is nowhere on Earth that can be “pioneered” or “settled” that has any value and that isn’t already under some government’s control.

Heinlein’s protagonists were settling worlds that were basically New Earths and suitable for farming. We have no knowledge of any such worlds. As our knowledge of biospheres and ecosystems has vastly expanded since Heinlein was writing his stories, we are less optimistic that such worlds would be suitable for human settlement or even that they should be.

Humans exploiting any world or moon are more likely to be like Asimov’s “spacers”, relying on robots to do the heavy lifting, not like Asimov’s “Earthers” or Heinlein’s gritty individualists recapitulating the colonizing of the N. American continent.

Exploiting and even settling another world is going to look a lot more like the exploitation of offshore oil, a project that requires huge capital resources and expertise that is aggregated into groups. Realistically, enough people and expertise is going to be needed to bootstrap an industrial economy.

There has in the last 4 or 5 decades been a repressive cultural attitude in the UK linking pioneering with colonialism, but there remains a strong streak of bloody minded individualism which given an area of outlet would gladly seize the opportunity to express its self and set off for horizons unknown.

I’m a bit dubious about limiting the pioneering spirit to Anglo-Americans. In the not too distant past, Russians pushed eastward into Siberia and southernly into the Caucusus region — Tolstoy wrote stories about such. In the 16th century Spaniards and Portuguese mariners split the world between themselves, and then were pushed aside by the French and the Dutch (and the English). A few centuries before that, Germany pioneers pushed through what became Prussia and Poland. And before that there were Vikings.

There’s an element in most societies, it strikes me, that would explore and loot or maybe even explore and settle, given proper circumstances. Perhaps we lack such circumstances. Other hand, it might be that the “proper circumstances” include poverty and desperation — something hinted occasionally in those Heinlein novels — in which case that modern humans seem to lack the essential spirit for pioneering might not be something to lament.

A particular concern of mine, and one of the reasons I advocate for a short term push to build von Neumann machines, (Which we should be capable of within just a couple decades if we try.) is the possibility that our push into space will be gradual, resulting in our population growing in proportion to our resources, and no faster.

Fast interstellar travel requires the expenditure of huge resources per mission, and if manned, even vaster per passenger. It isn’t going to happen unless our infrastructure grows enormously faster than our population.

Can’t you see that future: We expand into space, using chemical and solar powered rockets, and human dependent production, our population growing as we expand, until in the far distant future the Solar system is fully populated, without the excess resources to devote to a task as extravagant as interstellar exploration, because our needs have grown in synch with our capacities? The huge resources of the Solar system matched by a huge population.

In that scenario we probably still expand into the galaxy, comets and Kupier belt objects will eventually be colonized, and we’ll cross the interstellar depths by slow diffusion, as our own thinning constellation of objects blends imperceptively into the next stars’ cometary belt.

That’s not stagnation, as such, because we’d be spreading at the borders, but it’s not a glorious future of relativistic travel and a galaxy claimed by human kind in under a million years.

It’s a good point to note that a civilization slowly diffusing through its own planetary system could grow outward into the Kuiper belt and the Oort Cloud, and my the time there is a presence in the Oort cloud you’re almost half way to the next star. Sure conditions get more difficult the further out you go — less sunlight and fewer resources — but by the time this is possible the expanding civilization ought to have a great deal of experience in these matters.

I think it’s important to note that we do not yet know the economics of interstellar expansion. You suggest that fast interstellar voyages may be too expensive to sustain for a civilization focusing its resources on the maintenance of a vastly expanded population, but I think in the long term, if the technologies of fast interstellar travel prove to be practicable (this is something we also do not yet know), then this will be less expensive than the equally grand vision of a system-wide civilization building vast arks — generational starships — and sending them out into the cosmos.

As Darwin said, “There is grandeur in this view of life,” by which I mean the dispersion of life throughout the cosmos, whether by rapid relativistic means, in less than a million years, or by much slower means, which will come to maturity only over a billion years or more. The ultimate practicability of the various technologies we can now envision will be the deciding factor of the order of temporal magnitude of the dispersion of terrestrial life into the universe.

There is a lot in this post to discuss. :)

Regarding the term “stagnation”. Stagnation can mean different things. Discussed was ecological maximization. That limit can only be reached when the resources of the universe are fully and most completely used to green it. In our neck of the woods, that means creating a huge number of space habitats by dismantling the planets. The population size of such a civilization is many orders of magnitude larger than ours.

Economic growth is likely to stagnate too. Our recent historic rate of ~3% pa is not sustainable for very long. Exponential growth soon exceeds that of a Sol system. and surprisingly quite quickly reaches the limits of the galaxy. (< 1 millennium to expand 400 billion fold from a Sol sized economy.)

What isn't likely to stagnate is the sheer number of possible states that civilizations could attempt to create. Just recreating one small historical culture and replaying it so that chance changes outcomes would generate a vast number of new versions. That game has the capacity to rapidly exhaust all of space and time.

So as long as civilizations are not totally static, they should be able to evolve and create new information indefinitely, even if it means restarting from a defined historical and knowledge base periodically.

This is how I interpret the word stagant too.

It would not be a golden age civilization in complete lifelong vacation.

Perhaps part of the population might choose that, or to live in fantasy worlds created in habitats or computer generated illusion.

Earth today is already getting very close to the limit. Not because of technical limitation but because governments and industry choose to make products that drain limited resources and create harmful waste products.

Even if a super civilisation colonise all worlds and moons, or covert all matter completely in big engineering, there would still be economic activity.

And that activity could very well be in ecologic cycles, even if it might be from the collectors of whoopee cushions. ;)

Quote by J. Nielsen: “one that stagnated scientifically, but which expanded beyond its homeworld, and another that continued to expand the frontiers of scientific knowledge, but which stagnated on its homeworld—” This is impossible or science fiction. There is no such civilization that could have any kind of interstellar travel without scientific knowledge. There is no industry without physics or science.

Any civilization that started interstellar travel before us must be much more advanced than us. They evolved before us; Their star system most likely was born before ours or there home planet’s giant impact occurred before ours which would result in a faster evolution.

Based on today’s technological progress which is very slow, practical interstellar travel for people is two million years. This is a conservative view which does not include superluminal technology which might result in an earlier interstellar capability. We could have a breakthrough with FTL technology which would result in an earlier time but that time would still be long like a million years. The reason being is that it takes enormous energy.

There are world ships, but those are still ahead of our technology today. World ships suffer from the idea that they take too long to get too their destination or are too expensive and dangerous since we can send robot or automated craft or probes in the place or we might build a faster technology which would make them obsolete.

That’s not really true; There’s still Orion, which may be banned by treaty, but is still within our current technology, and capable of manned interstellar flight on the order of a few percent of C.

Depending on the civilization, interstellar travel could be easy. Very easy. There would be a single massive wave of colonization when the parent civilization builds a hundred billion ships and sends them out. Even at a mere 1/1000th of the speed of light it would only take 100 million years to fully colonize the galaxy. Of course they would be self-repairing robotic ships, but they would be able to recreated the builders once they arrive.

Perhaps that explains the Fermi paradox. 400 million years ago someone did just that and colonized all the rocky planets with high levels of oxygen in their atmosphere. The Earth, not having a high level of oxygen, didn’t get colonized. Then the civilization stagnated, or evolved, or is planning a second wave every 1 billion years to grab planets like the earth. Sure the idea has problems, but so does every Fermi paradox solution.

Even with our current technology we could, with enough time and motivation, build an Orion style interstellar vessel. Whether or not the crew could build a new civilization upon arrival is in question though.

SETI, in my opinion, is not about saying we shouldn’t become an interstellar species, but about looking where we’re going rather than taking a blind leap and trusting only in faith that we can hope to know where we will land. People don’t put on a blindfold when they get into a car to drive – they used both eyes to watch where they’re going. Those that don’t might avoid the inevitable for a while, but will eventually end up in an accident. Few people/civilizations will suvive playing a thousand rounds of Russian Roulette.

The conservative view is that we won’t have interstellar travel for two million years but it could come sooner due to technological breakthroughs.

Laws of nature aren’t absolute in the sense that elements after Pu-239 can be produced artificially but they almost never appear naturally. Of course there is no way in hell for some random exotica with 1M proton + 1M neutron to exist naturally or artificially; the real limits are based in mathematical consistencies but when one stays too far from the physical boundaries, this becomes SF delusions.

I too am very skeptical that interstellar travel won’t happen in some form. There are just too many options from low tech to high tech and different acceptable time frames.

I personally suspect that our post-human travelers will be synthetic, the “robot” option [IIRC] from a previous post by Nielsen. Like spaceprobes that can have their software changed by remote upload, such synthetics might well offer a way for minds to travel between the stars, whether by em signals or by physical media. Careful timing would allow groups to experience communication with different civs and yet still regroup at the same time and place in the future.

Communication can be “blurred” in meaning if a civ sends a data dump of its state with an AI that could converse with the target civ. While it doesn’t meet the criterion of a civ-to-civ conversation, perhaps we need to think less about such homeworld to homeworld conversations and just accept that travelers meeting still constitutes useful exchange that might eventually affect the descendants of the participating civs. Historically, had none of Columbus’ crew ever returned home, would the communication between his crew and the American natives not have constituted a communication even though Spain did not get to participate?

As in my previous comment, I think this allows any encompassing super-civ to endlessly explore new patterns that will continue to find new ones until the end of the universe.

A good post…

By 2035 the High definition Space Telescope with its 40 foot mirror orbiting the sun should keep your curiosity percolating…There are too many unknowns concerning super-civilizations…Somebody here said only yesterday that we are a sample of one…stay patient…be prepared for surprises…new knowledge changes so many suppositions…Look where America was in 1835…Lucky America changes…Ancient Rome didn’t change…they went back to the land and abandoned Rome…Now Rome has regenerated despite all the tough centuries…You’ve read Asimov and the Foundation and Hari Seldon…regeneration is one of nature’s favorite paths…regardless of who says what…

I am old enough to remember the late 1940’s-early 1950’s uproar over “breaking the Sound Barrier”. All sorts of high-IQ’s were sure it couldn’t be done, and if attempted the result would be fatal for pilot and plane…this even though quite a number of WW2 pilots claimed they had already done so, with no ill effects other than “compressibility”. And then what’s-his-name and the X-1 did it under measured conditions, and that was that. Exactly the same will prove true for the Light Barrier, IF ours or some other galactic civilization lasts long enough. And therein lies the problem. As I explained before,

1) intelligent civilizations involving creatures w/o hard-wired inhibitors against massacring their own kind – e.g., us – enter the nuclear funnel and generally don’t come out. Actually, we’ve caught one enormous break in this respect – see if you can figure out what it is – and so just may navigate through, though I doubt it.

2) those with hard-wired inhibitions against intra-specific massacre can last much longer – even long enough to attain both FTL travel and communication – but sooner or later encounter another suchlike and destroy one another in a Sector War. So at any given time there’s no more than a half-dozen or so of both civilizational types spread randomly across and through the c. 100,000,000 cubic light years of our galaxy. Thus the Great Silence. One thing for sure, E.O. Wilson et. al. notwithstanding: if somehow we murderous, strip-mining humans do get through the nuclear (and other) funnels, the Milky Way Galaxy is eventually going to become a noisy place indeed.

The question at that time, as I understand it, wasn’t whether the “sound barrier” could be broken, (Clearly it could, bullets did it all the time!) but whether people could survive doing it.

And, honestly, there really wasn’t any technical reason to suppose it was impossible to survive, unless maybe you were in an open cockpit plane at the time.

I think these claims were more on a par with the Smalley attacks on the feasibility of nanotechnology. Sometimes a group of “experts” have non-scientific reasons for wanting to declare something impossible, and confuse those motives with scientific reasoning.

Faster than light travel is rather different, we actually do have all sorts of reasons to believe it impossible, and precisely no examples of anything that travels FTL.

galaxies beyond the visible “edge” of our universe are accelerating away from us at greater than lightspeed. That’s why we can’t see them. They do so by stretching/warping spacetime. I expect that, by controlling dark energy, we can eventually do so as well.

http://youtube.com/watch?v=yCCsmxGjEV0

800 years ago, the idea that the planets and sun rotated around the earth was actually good science. Geocentric models adequately explained the rotation of the planets until advent of telescopes. The copernican model did not make predictions any better than the geocentric model. The time from copernicus manuscript to gaileo was 100 years. When heliocentrism became dominant, not only did the view of the solar system change so did the view of the universe since heliocentrism required stars to be much more distant. If FTL travel is possible then the science needs to catch up with the theories.

Honestly, comparing the sound barrier with the light barrier is a very bad analogy. They are entirely different things.

First off, there was no question whether the so-called “sound barrier” could be broken. Bullets and whips have been breaking the sound barrier for centuries (indeed, the sound of a whip crack is a small sonic boom). The question was purely whether an aircraft could break the sound barrier in controlled flight. Earlier aviators found things to behave quite differently in the transonic regime once their aircraft hit those speeds, and tended to lose control.

But we know of nothing that travels faster than light, locally. And relativity, which is supported by a rather convincing amount of evidence, suggests that nothing that carries energy or information can outrace light. Worse, if we assume something can anyway, in relativity you can construct scenarios in which FTL trips result in time travel and causality violations.

All that the statement “they said we’d never break the sound barrier, but we did, so the light barrier will be the same” expresses is a blind faith that every predicted natural limit to our activities will be overcome by human ingenuity and technology. It’s equivalent to stating that there are no natural limits on our activities, and this is simply not true. Just look at the history of perpetual motion.

First off, this is a commonly repeated misconception. See misconception #3 in this paper: Expanding Confusion: common misconceptions of cosmological horizons and the superluminal expansion of the universe. Also the expansion of the universe is something rather different than a speed, so cosmologists complain that saying the universe expands faster than light is hopelessly incorrect. See this post explaning why the universe never expands faster than the speed of light.

That aside, you are referring to the Alcubierre Metric. The idea that a spacecraft might achieve apparent FTL but riding a wave of expanding and contracting spacetime is intriguing, but unfortunately it’s still an entirely mathematical construct that may not be physically meaningful. Galaxies do not travel faster than light by warping spacetime. They, like us, are embedded in the expanding spacetime of the universe. Alcubierre Drive requires controlling or “engineering” spacetime, an entirely different matter.

And you need negative mass (typically an astronomical quantity of it) to create this metric, not dark energy. Assuming we can figure that out, we then have the issue of controlling the bubble (which is disconnected from the ship inside it), being fried by Hawking Radiation at superluminal speeds, and accidentally destroying the destination once you arrive. And you still have the possibility of causality violations. The concept definitely deserves attention, but don’t count on it leading to warp drive. If a physics breakthrough is uncovered (read, if the universe turns out to work the way we’d like it too), just maybe it might. But it could just as easily be impossible to construct.

Humanity is a primitive race, driven by reproductive urges and engaging in murderous wars. Our home world is threatened by destructive cosmic events. Our environment is our own cesspool. As a species considered as a whole, our objectives are sex, food, entertainment, and comfort. We seem more likely to obtain our needs by taking from others rather than to produce our own. Our view of the universe seems to be an extrapolation of our current experience. I do not know if it is possible for any human to imagine what a successful long term civilization would be. I do not that we would want it if we could so imagine. A hive society come to my mind . . .

Our society has stagnated for over a hundred years when you look at the average person use of power, the HORSEpower of the sacred automobile! When society excepts EmDrives, LENR (Cold Fusion) and the ability to transmute elements, then and only then will we become a planetary society that can really contemplate the possiability of intersteller travel in a knowledgeable way. The wisdom embedded in the quantum universe will lead us to understand and fathom the electromagnetic properties of the photon and its relation to the electrons phase locked cavities, the base root of all energy and the key to interstellar travel.

Wonderful article.

And surprisingly, this has to be repeated and to justify again and again.

The idea of the possibility of interstellar travel in the star approaches described well-known geologist and paleontologist Ivan Efremov in his book “Star ships” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stellar_Ships). Now the story about the aliens among dinosaurs looks corny, but the book was written before the end of the Second World war.

About interstellar flights in globular clusters wrote V. G. Surdin in the 1980s (?????? ?.?. ??????? ???????? ????????? ??? ??????? SETI // ??????????????? ????????, ? 1357, ?. 3-6, 1985.).

In addition, the movement of the stars can be controlled in the presence of very limited resources, and these technologies are also already known (Shkadov, L. M. “Possibility of controlling solar system motion in the galaxy, «38th Congress of the …», October 10-17, 1987, Brighton, UK, paper IAA-87-613.).

This completely changes the paradigm of interstellar flight as a contradiction with the life on the inhabited planets (by Edward Wilson, etc.), as the contradiction is removed.

Literally in the near future I will present material on this subject.

Thanks. I should have mentioned the Shkadov thruster in this post, as it operates over the time scales I examine in this essay, and it would speed up the process of bringing other planetary systems within easy spacefaring range of a civilization without exotic drive technologies. The idea of a Shkadov thruster is pretty basic, the question, then, would be whether building a Shkadov thruster around one’s own star would take engineering expertise beyond what could be expected from a rudimentary spacefaring civilization. Obviously, we could define a number of stages of spacefaring sophistication and differentiate those capable to carrying this off, and those not so capable. The distance scales of the universe would then become a strong selective effect: those civilizations capable of mastering the engineering of a Shkadov thruster would have “first mover” advantage in settling the galaxy and displacing any lower technology rivals, or leaving nothing available (no unoccupied real estate) for Johnny-come-lately spacefaring civilizations.

See https://i4is.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Principium18%20Aug2017%20opt.pdf (pp. 31-41) as one variant.

Perhaps as inportant as anything else are societal, cultural, political, moral and ethical considerations. Less than altruistic motivations and actions, fouling our own cosmic nest, lack of perspective in managing non-renewable resources can each severally and jointly do us in, and might well be likely to do so.

There’s an Italian chap here at the door asking “Where are they?”

In fig 1 , I take it to be figure 1, what are the uncertainties associated with each of the components? What are error bars associated with the curve?

As we do not yet possess a quantifiable model of civilization (unless you count Turchin’s cliodynamics), we don’t have any numbers associated with components on the graph. If some tech billionaire would like to drop in endowment in my lap, I would gladly set up a research institution devoted to the study of civilization, and which might eventually start filling in the numbers for the graph above.

In my uncertified intellectual opinion…

Interstellar travel is not a heck of a lot more likely than FTL travel.

The former requires the latter.

This must not be easy to do; if it was, then the Fermi busters of the galaxy would be buzzing around regularly.

Einstein did NOT have the whole picture (neither did Newton, neither did Bohr). But every one of Albert’s predictions based on his incomplete theory have proven correct (compare Albert’s list to those of String Theory). Now add gravity waves to the list.

I don’t think FTL is normal, quantum gravity space is possible, else everyone out there would be doing it. Or if no one is out there.

Unless a way can be found to do an end run around relativity, to cheat Einsten, then we’re stuck in the solar system.

Yes, slower than light can be done, and it SHOULD be done. But to get to supercivilization status that way would take a very long time indeed. Without the FTL, humans cannot get there. Robots, the future belongs to you.

Why did the galaxy have to be so big?? I know, for no reason.

think of it as a quarantine system.

I think the answer to Fermi’s paradox is the difficulty of abiogenisys. The universe is full of lifeless sterile worlds waiting for humans to spread the seed of life.

Let’s just keep trying to explore and get out there any way we can. Our species will always have a finite biological lifespan but with future technology likely to increase that we have an incredible opportunity to explore if we don’t destroy ourselves. At the very least we will be able to send machines to nearby starts very soon. I’m very skeptical about super civilizations but possibly only because I lack enough imagination. There are many negative feedback loops as well as positive ones that may prevent a super civilization from dominating even one galaxy.

Becoming that civilization must be our goal, starting where we are.

We still have many possibilities for the buildout of spacefaring civilization, and we still have many possibilities for failure. Suboptimality occupies a position somewhere between a glorious onward and upward future on the one hand, and, on the other hand, ignominious failure.

About civilizations reaching carrying capacity:

First, as a formerly expanding civilization reaches the limits of resources there may be a tendency to overshoot, due to the inertia of a civilization reforming itself from the values of an expanding “frontier” (in figurative terms of development if not literally in terms of colonization) culture to a steady-state culture. Thus a civilization might temporarily over-utilize finite resources, then suffer a crash due to their depletion, before finally reaching an equilibrium. The curve showing the civilization’s approach to K the carrying capacity might have a squiggle or two of over/undershoot before leveling out at K.

Second, the maximum utilization of resources possible given the laws of physics may not be realized in one go. A civilization might reach the limits of the technology available to it, fall into a near-steady state for a period, and only then make a technological breakthrough which wasn’t possible until a sufficient economy of scale was reached. To imagine one hypothetical, it might be possible to develop a technology based on manipulating gravity but only after engineering on a literally astronomical scale becomes practical: creating artificial neutron stars from stellar-mass quantities of iron for example. So the approach to the absolute limits to what’s physically achievable may characterized by a number of temporary plateaus rather than a single development curve.