It’s worth thinking about why Voyager 1 and 2, now coming up on their 40th year of operation, are still sending back data. After all, mission longevity becomes increasingly important as we anticipate missions well outside the Solar System, and the Voyagers are giving us a glimpse of what can be done even with 1970’s technology. We owe much of their staying power to their encounters with Jupiter, which demanded substantial protection against the giant planet’s harsh radiation, a design margin still used in space missions today.

The Voyagers were the first spacecraft to be protected against external electrostatic charges and the first with autonomous fault protection, meaning each spacecraft had the ability to detect problems onboard and correct them. We still use the Reed-Solomon code for spacecraft data to reduce data transmission errors, and we all benefited from Voyager’s programmable attitude and pointing capabilities during its planetary encounters.

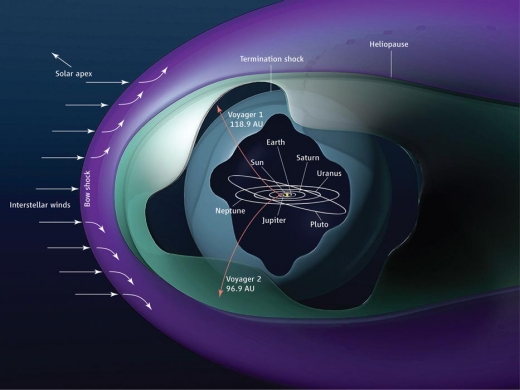

Pioneer 6 was a doughty vehicle, but Voyager 2 (launched before Voyager 1) passed its record as longest continuously operating spacecraft back in August of 2012, while Voyager 1 eclipsed Pioneer 10’s distance mark in 1998 and is now traveling some 21 billion kilometers out. Voyager 1 is our sole spacecraft to leave the heliosphere, though Voyager 2 is expected to follow it in a few years, and we’ve already acquired important information, such as the fact that cosmic rays are four times more abundant in interstellar space than near the Earth.

You can see how all this begins to build the foundation for a ‘true’ interstellar mission, by which I mean one designed solely for the purpose of penetrating the local interstellar medium and reporting data from it. The heliosphere, Voyager has shown us, wraps around our Solar System and helps to provide a radiation shield for the planets. Missions both robotic and manned will need to be designed around the cosmic ray issues Voyager has uncovered.

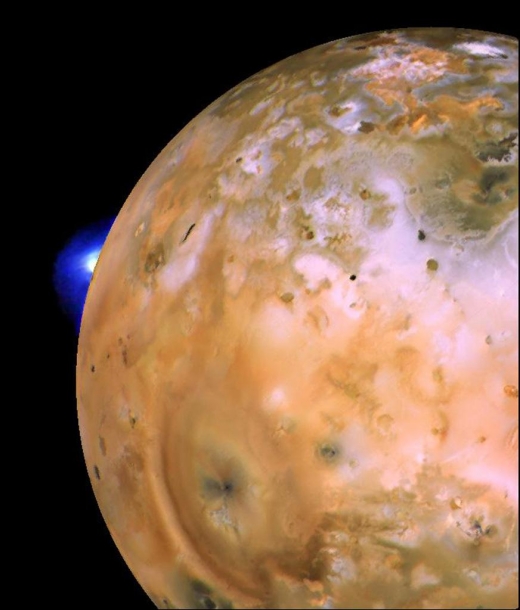

Image: Voyager 1 image of Io showing active plume of Loki on limb. Heart-shaped feature southeast of Loki consists of fallout deposits from active plume Pele. The images that make up this mosaic were taken from an average distance of approximately 490,000 kilometers. Credit: NASA/JPL/USGS.

Still thinking interstellar, the Voyagers are telling us about the solar wind’s termination shock, that region where charged particles from the Sun slow to below the speed of sound as they push out into the interstellar medium — these are Voyager 2 measurements. Voyager 1 has measured the density of the interstellar medium as well as magnetic fields outside the heliosphere. The final benefit: We’ll have Voyager 2 outside the heliosphere while still in communication, so we can sample the interstellar medium from two different locations.

I always think of long spacecraft missions in terms of the people who work on them. Voyager is pushing on the ‘lifetime of a researcher’ rubric that some consider essential (though I disagree), the notion that missions have to be flown so that those who worked on them can see them through to destination. But of course the Voyagers have no destination as such; they’ll press on in a galactic orbit that takes fully 225 million years to complete. And as our spacecraft get even more rugged and capable of autonomy, we’ll soon take it as a given that multiple generations will be involved in seeing any complex mission through to completion. (See Voyager to a Star for my riff on a symbolic ‘extension’ to the Voyager mission).

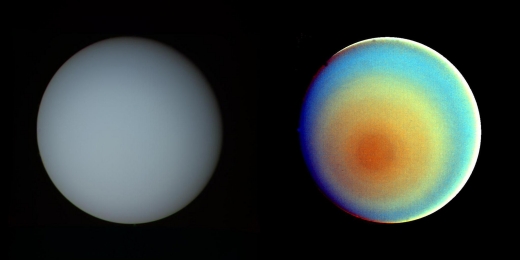

Image: These two pictures of Uranus — one in true color (left) and the other in false color — were compiled from images returned Jan. 17, 1986, by the narrow-angle camera of Voyager 2. The spacecraft was 9.1 million kilometers from the planet, several days from closest approach. The picture at left has been processed to show Uranus as human eyes would see it from the vantage point of the spacecraft. Credit: NASA/JPL.

We have, according to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, perhaps until 2030 before data from the Voyagers ceases. Each spacecraft contains three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) running off the decay of plutonium-238. And as this JPL news release reminds us, with the spacecraft power decreasing by four watts per year, engineers have to be creative at figuring out how best to squeeze out data results under extreme power constraints.

For a mission this long, that means consulting documents written decades ago and at a completely different stage of technological development.

“The technology is many generations old, and it takes someone with 1970s design experience to understand how the spacecraft operate and what updates can be made to permit them to continue operating today and into the future,” said Suzanne Dodd, Voyager project manager based at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena.

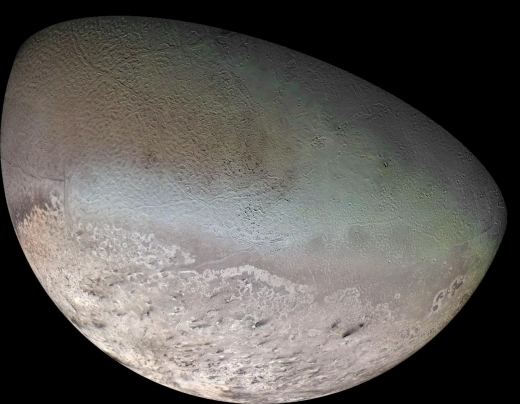

Image: Global color mosaic of Triton, taken in 1989 by Voyager 2 during its flyby of the Neptune system. Triton is one of only three objects in the Solar System known to have a nitrogen-dominated atmosphere (the others are Earth and Saturn’s giant moon, Titan). The greenish areas include what is called the cantaloupe terrain, whose origin is unknown, and a set of “cryovolcanic” landscapes apparently produced by icy-cold liquids (now frozen) erupting from Triton’s interior. Credit: NASA/JPL/USGS.

It’s been quite a ride. Voyager discovered Io’s volcanoes and imaged rings around Jupiter, Uranus and Neptune, while finding hints of the apparent ocean within Europa that carries so much astrobiological interest. Between them, the Voyagers found a total of 24 new moons amongst the four planets they visited, detecting lightning on Jupiter and a nitrogen-rich atmosphere at Titan, the first to be found outside the Earth itself. And who can forget that bizarre terrain on Triton, or the tortured surface of Uranus’ moon Miranda?

“None of us knew, when we launched 40 years ago, that anything would still be working, and continuing on this pioneering journey,” said Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist based at Caltech in Pasadena, California. “The most exciting thing they find in the next five years is likely to be something that we didn’t know was out there to be discovered.”

Image: The Voyagers outbound. A representation of the heliosphere, including the termination shock (TS), the heliopause and the interstellar medium where the heliosphere ends. Credit: Science, NASA/JPL-California Institute of Technology. Note: In this image, the locations of the Voyagers are updated only to September 2011, by Brad Baxley, JILA.

Who knew that Voyager’s measurements of solar wind plasma, low-frequency radio waves, charged particles and magnetic fields would still be informing us fully forty years on? The next spacecraft to cross the heliosphere after Voyager, this time designed for just that purpose, will surely live even longer, challenging our conceptions of human achievement across generations and our willingness to tackle projects involving not just deep space but deep time.

This mission isn’t over. Go Voyager.

Thank you, Paul, for this lovely — and loving — look at Voyager’s mission.

You bet, Michael. I always love to write about Voyager.

Great post. Could you explain what “speed of sound” means in this context: “that region where charged particles from the Sun slow to below the speed of sound as they push out into the interstellar medium”?

By which I meant–sorry–is it just that the particles slow to below ~343 m/s, or is there some meaning to the speed of sound (it would have to be *extremely* low-frequency sound) in the interstellar medium, which is almost, but not quite, a vacuum?

I assume this does indeed mean extremely low-frequency sound through a medium that is not a perfect vacuum. 343 m/s is the speed of sound in the atmosphere under specific conditions.

Corrections welcomed because this is just a quick take on the matter, and there are those here who can explain it far better than I: The solar wind — charged particles from the Sun moving at high velocity — encounters the interstellar medium (varying densities of gas and dust) as it nears the ‘termination shock.’ Eventually the pressure of the ‘wind’ drops below supersonic flow as measured against the pressure of the medium. The figure I’ve seen for this ‘speed of sound’ value is about 100 km/s, but it varies depending on the density of the medium. The heliopause is where the interstellar medium and solar wind pressures balance.

The solar wind plasma is dominated by the Sun’s magnetic field, and so the analog to sound (pressure) waves in air are Alfven waves in the plasma. When scientists talk about supersonic or subsonic flows in the solar wind, heliopause, etc., they are comparing the flow speed to the local Alfven velocity, v_A, which is ~ B / sqrt(mu_0 rho), where B is the field strength, mu_0 the permeability of the vacuum and rho the mass density of the plasma. At 1 AU (near the Earth, but outside its magnetosphere), v_A is about 35 km/sec while typical flow speeds are maybe 400 km/sec. Such flows are described as supersonic, with a Mach number of order 12, but this is in reference to v_A.

Excellent, Marshall. I knew one of the readers would have a much more insightful take on this issue. Thanks!

An Irish documentary about the incredible Voyager spacecraft is getting huge praise:

http://www.thejournal.ie/the-farthest-movie-3518061-Jul2017/

To quote:

Beyond the topic at hand, what’s particularly striking about The Farthest is the number of women who worked on it. I ask Reynolds about this, and how it may tie into the recent moves by the Irish Film Board to address gender imbalance in Ireland’s film industry.

“It’s wonderful now to see, the change is so positive and it’s so dynamic. And it’s a real turning of the wheel, which I really applaud,” says Reynolds of the deliberate steps to bring about gender parity. Over the years she worked as a film editor, just a “minuscule fraction” of the directors she worked with were women.

“Encouraging women into key positions is fantastic for everyone,” she says. The film itself reflects that.

“We took it as read that women’s voices would be loud and proud in it,” says Reynolds. This also reflects the growth in acknowledgement of women’s role in scientific discoveries, such as the film Hidden Figures.

After the documentary was shown at the Audi Dublin International Film Festival, Reynolds got three letters from young girls (two aged 10 and one aged 12) telling her they want to be scientists.

“I was like, ‘my work is done’,” says Reynolds. “That was the thrill of a lifetime, for me to inspire them.”

I think this is the documentary that PBS will show on August 23. An ad for a documentary called “The Farthest – Voyager in Space” has been showing up on my social feed and there is a release about it on spaceref:

http://www.spaceref.com/news/viewpr.html?pid=51175

Yes they sound like one and the same.

You might also find this video of interest – a collection of NASA videos showing everything from Voyager being assembled to launch and mission highlights:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ihcG79sakaA

And this one – Voyager: Journey to the Stars:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=seXbrauRTY4

‘It’s a romantic attempt to describe how we are as humans to an extra-terrestrial audience’

Emer Reynolds’s new film ‘The Farthest’ looks at the extraordinary, humbling story the Voyager space project.

Sat, July 29, 2017, 05:00

http://www.irishtimes.com/culture/film/it-s-a-romantic-attempt-to-describe-how-we-are-as-humans-to-an-extra-terrestrial-audience-1.3165339

To quote:

Interestingly, the Voyager crew have mixed feelings about the famous “golden record” that each craft carries. This is a gold-plated copper LP, packed with a needle, cartridge and instructions, and containing, in groove form, photos from Earth, a selection of natural sounds, plus music from a variety of cultures and eras. Tracks include Chuck Berry’s Johnny B Goode, Glenn Gould performing from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier, and a pygmy girl’s initiation song from Zaire.

Carl Sagan, the project supervisor and astrophysicist, had wanted to include The Beatles’ Here Comes the Sun, but EMI turned him down, saying “We don’t licence for outer space.” There are, additionally, spoken greetings in 55 languages, including such ancient dialects as Akkadian and Hittite. The Amoy message asks: “Friends of space, how are you all? Have you eaten yet? Come visit us if you have time.” Nick Sagan, the Star Trek writer and son of Carl Sagan, recorded the English message as a child: “Hello from the children of planet Earth.”

“I think one of the great things about Voyager is that it just naturally has these two pieces to it,” says Reynolds. “The heart and the mind. It combines extraordinary scientific discoveries and achievement with this romantic attempt to describe how we are as humans to an extra-terrestrial audience. This little craft built in the 1970s is knocking it out of the park in terms of science. But it also has this amazing golden record attached to the outside of the craft which is insane that is trying to communicate with aliens. It has everything we are as people.”

A truly historic mission of the highest caliber.

The plot justification for the movie “Space Cowboys”.

I agree with Paul’s take on the matter. The reason for needing someone with 1970s design experience to squeeze every ounce of power out of the Voyagers is that the probes were never designed to travel to the interstellar medium. The fact that they have had such a long and productive life is truly a testament to those who worked on them.

That being said, I do not believe a mission that stayed within its original design parameters for its entire duration (be it 10-100+ years) would run into such problems. The farther out we go, the more it becomes clear that space exploration is a generational endeavor.

A possible mission to near interstellar space using current technology (Innovative Interstellar Explorer) was described here on Centauri Dreams a few years ago:

https://centauri-dreams.org/?p=21050

It would have a 30 year flight time to 200 a.u. Launch windows occur every 12 years because the proposed mission uses a gravity sling around Jupiter.

Unfortunately for me, even if IIE launches in the next available window (2026) I’ll be 100 years old when it gets to 200 a.u., so I’m certainly interested in faster alternatives!

Take more than a little comfort in knowing that your descendants among many others will benefit from such a mission. Too many other things in modern society are so transient.

I picture the far future where it takes only days to get to

a Pluto orbit, as part of a Solar System Safari, you get

to rendezvous with VOYAGER.

Not only that as your ship matches speed,

It will be brought into a large cargo bay where you may lay hands

on it, a mobile Stonehenge if you will.

At first only the very wealth would afford it,

after a few centuries, it will be a required field

trip for young students.

You will probably get a kick out of this future scenario for Voyager 1 from Orion’s Arm:

http://www.orionsarm.com/eg-article/49f9b4b02ce26

“I picture the far future where it takes only days to get to

a Pluto orbit, as part of a Solar System Safari, you get

to rendezvous with VOYAGER.”

Unless you had adamantium bones, you would be pretty dead by then–unless by “only days” you meant a couple of months.

Antonio, trying to be poetic but.

Granted at 3 g acceleration in six days, gets you in the ball park of Neptune orbit.

The future has a ship with all that acceleration and military

aps people haven’t solved the High G obstacle? unthinkable.

Civilian application usually follows military ones.

I think it’s quite more than 3 g. This was my back of the envelope calculation:

Pluto is 5.5 light-hours from the Sun. If you want to reach it in “only days” you need, say, 0.1 c. To reach 0.1 c at 1 g it would take around a month, but, since you will do Pluto orbit insertion, you would need to decelerate, so that would be 2-3 months at 1 g. If you want to accomplish the same trip in only days instead of 2-3 months, you will experience acceelerations in the order of 20-30 g or so during days. You would be carrying the weight of 20-30 people during days.

Not that I am complaining, but I thought that the Voyager probes would run out of useful power by 2025, not 2030. When did this date change?

Regarding Pioneer 6, token contact was made with the satellite in 2000, but has anyone checked since? Wikipedia says of all the members of this particular group of Pioneers, only Number 9 is definitely no longer functional. The rest (6, 7, and 8) may still be reachable. It would be nice if someone tried, especially if they have still been collecting solar data since the late 1960s!

I’m beginning to see 2030 as a terminus, assuming all but one instrument on each spacecraft turned off.

The Sun-orbiting Pioneers (6, 7, and 8) interest me as well. So do ISEE-3 and Giotto (which–if memory serves–was placed in hibernation after its second comet encounter, with Grigg-Skjellerup in 1992). All five of these spacecraft (and perhaps others in solar orbit) might possibly still be active (or “awaken-able”), and if so, they could return solar data, and:

Both Pioneer 7 (which made a distant flyby) and Pioneer 12 (the now-gone Pioneer Venus Orbiter, which took measurements and images from afar), investigated Halley’s Comet (in fact, a 1974 Hughes Aircraft booklet on the then-upcoming Pioneer Venus mission proposed using spacecraft of the orbiter’s design for solar-orbiting comet flyby spacecraft). With so many short-period comets–and the occasional long-period one–crisscrossing the inner solar system, the old solar-orbiting spacecraft may pass close enough to some of them to gather useful data. Using these old spacecraft for this would be a cheap way to acquire new knowledge about never-before-visited comets.

“Voyager is pushing on the ‘lifetime of a researcher’ rubric that some consider essential (though I disagree), the notion that missions have to be flown so that those who worked on them can see them through to destination.”

Well, ‘lifetime of a researcher’ is not a constant at all. Life expectancy has been increasing at a quite constant pace of around 3 months per year in the developed world for quite a long time now. For example, in the US, male life expectancy in 2013 was 9 years longer than in 1973.

Not only ‘Lifetime of a researcher’ is necessary but funding. I am sorry many do not understand how research work is done and funded.

Profit run research coporation: Your project will not even get started.

Private research institute: You have to apply for funds for your research project, it have to compete with proposal with close or immediate results. Your proposal will never get granted.

Government institute/university: The project to build a probe to fly for generations could be started, but a scientific career is built on the published results, without result you’ll be seen as failure and loose funding. It will not be finished if it’s not one closer goal to reach.

(Blue sky research is now unusual, trend is to have immediate application. We have found something new and unexpected, but we do not have funds in 2018-2022 period or perhaps ever, and we cannot finish the studywork properly.)

Sorry I digress. But this the reason there is 2 more missions to asteroids now instead of Uranus and Neptune & Triton (or Titan). Long lasting daring missions do not get approval.

Don’t forget (134340) Pluto!

It took 40 years for simple and wonderful automatic probes to slowly reach the solar wind border in our star system …

Only now (see last image) the probes begin to feel the wind … the wind of the stars of the galaxy …

I like to imagine how many “pietas” …THEY look at us amused and silent, waiting for us to invent a futuristic technology that allows us to move between the stars ….

As other civilizations already make millions or billions of years, even without metal hulls …

The Loyal Engineers Steering NASA’s Voyager Probes Across the Universe

As the Voyager mission is winding down, so, too, are the careers of the aging explorers who expanded our sense of home in the galaxy.

By KIM TINGLEY

AUG. 3, 2017

In the early spring of 1977, Larry Zottarelli, a 40-year-old computer engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, set out for Cape Canaveral, Fla., in his Toyota Corolla. A Los Angeles native, he had never ventured as far as Tijuana, but he had a per diem, and he liked to drive. Just east of Orlando, a causeway carried him over the Indian and Banana Rivers to a triangular spit of sand jutting into the Atlantic, where the Air Force keeps a base. His journey terminated at a cavernous military hangar.

A fleet of JPL trucks made the trip under armored guard to the same destination. Their cargo was unwrapped inside the hangar high bay, a gleaming silo stocked with tool racks and ladder trucks. Engineers began to assemble the various pieces. Gradually, two identical spacecraft took shape. They were dubbed Voyager I and II, and their mission was to make the first color photographs and close-up measurements of Jupiter, Saturn and their moons. Then, if all went well, they might press onward — into uncharted territory.

It took six months, working in shifts around the clock, for the NASA crew to reassemble and test the spacecraft. As the first launch date, Aug. 20, drew near, they folded the camera and instrument boom down against the spacecraft’s spindly body like a bird’s wing; gingerly they pushed it, satellite dish first, up inside a metal capsule hanging from the high bay ceiling. Once ‘‘mated,’’ the capsule and its cargo — a probe no bigger than a Volkswagen Beetle that, along with its twin, had nevertheless taken 1,500 engineers five years and more than $200 million to build — were towed to the launchpad.

Full article here:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/03/magazine/the-loyal-engineers-steering-nasas-voyager-probes-across-the-universe.html

To quote:

They relieved stress with games and pranks: bowling in the hallway, using soda cans as pins; filling desk drawers with plastic bags of live goldfish; making scientists compete in disco-pose contests. Now, by 1990, they were older, with kids of their own. They had experienced the deaths of colleagues and watched others’ marriages falter as a result of long hours at the lab. With no planets to explore, they spent the decade doing routine spacecraft maintenance with a fraction of their bygone manpower. Six of the current nine engineers were on the team then. Sun Kang Matsumoto, who joined the mission in ’85, studied so diligently to master the new roles pressed upon her that her sons learned the spacecraft contours by osmosis. When her eldest was 8, he surprised her with a perfect Lego model; now in college, ‘‘he calls and asks, ‘How is Voyager?’ Like, ‘How is Grandma?’?’’ Matsumoto says.

August 2, 2017

Two Voyagers Taught Us How to Listen to Space

As NASA’s twin Voyager spacecraft were changing our understanding of the solar system, they also spurred a leap in spacecraft communications.

The mission’s impact is still visible in California’s Mojave Desert. There, at NASA’s Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex, the arcs of antenna dishes peek out over craggy hilltops. Goldstone was the first place where the two Voyagers started to change the landscape. The farther they traveled, the bigger these dishes needed to be so they could send and receive radio waves necessary to track and communicate with the probes.

Starting in the 1970s, construction crews built new dishes and expanded old ones. These dishes now tower over the desert: the largest is 230 feet (70 meters) in diameter, a true colossus. Its smaller siblings are 112 feet (34 meters) in diameter, longer than two school buses at their widest points. The dishes had to grow from their original 210 feet (64 meters) and 85 feet (26 meters), respectively.

The expanded dish sizes were mirrored at NASA’s other Deep Space Network (DSN) sites, located in Madrid, Spain, and Canberra, Australia. The DSN is managed by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California, under the direction of the agency’s Space Communication and Navigation (SCaN) Program.

The Voyager mission helped drive this evolution. Today, the Voyagers are more than 10 billion miles from Earth, and Voyager 1 has gone past the heliosphere — the bubble containing the Sun, the planets and the solar wind. The vast distances between the probes and Earth have required bigger and better “ears” with which to hear their increasingly faint signals.

“In a sense, Voyager and the DSN grew up together,” said Suzanne Dodd of JPL, director of the Interplanetary Network Directorate and Voyager’s project manager since 2010. “The mission was a proving ground for new technology, both in deep space as well as on Earth.”

Full article here:

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=6910

To quote:

“Today, space agencies borrow antennas routinely to help each other, something which began with Voyager,” said Leslie Deutsch of JPL, deputy director of the Interplanetary Network Directorate. Deutsch helped research how to perform NASA’s first arrays and how to incorporate the non-DSN antennas into that work.

That is very true–the large dish at Japan’s Usuda station was–in concert with the upgraded Deep Space Network stations, of course–largely responsible for Voyager 2 being able to return data and images on/of Neptune and Triton, and at about the same data rate that was achieved during the Uranus encounter, even though Neptune is a billion miles farther from the Sun than Uranus!

NASA is doing a little METI for Voyager’s 40th anniversary:

Send a #MessageToVoyager!

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/voyager/message/?linkId=40511443

And a new article on the Physical METI attached to the twin Voyager space probes:

https://psmag.com/magazine/how-to-make-friends-in-outer-space

To quote:

The big questions about alien life tend to ask some variation of “Are we alone in the universe?” Sagan’s team operated from the assumption that we aren’t, and asked instead how we might appear to our new alien friends in the best possible light. “Why not a hopeful rather than a despairing view of humanity and its possible future?” as Sagan wrote in Murmurs of Earth, his 1978 account of the making of the records. So even as the records contain feel-good scenes of humanity and nature (for example, a portrait of a woman in a floral dress breastfeeding a baby, and a shot of a field of flowers—deliberately chosen for their visual resonance), the team included no depictions of war, disease, poverty, environmental loss, anger, or loneliness. There is, of course, a hint of loneliness suggested by the very existence of the records—gold-plated invitations to potential friends. Like anyone looking to play host, we wanted to impress. But the decisions were more complicated than that. Images of war—and especially of weaponry—would have been too potentially ambiguous to risk. If this was our one chance to make contact, we had to get it right.

The Voyager probes are a prime example of what we can accomplish with long-term thought and action. Even if the original designers never intended the mission to pay out dividends this long, we still owe all this to their rugged and reliable engineering work.

As others have pointed out, our culture emphasizes the near-term. We want return on investment, and conclusions to publish within a few years. It’s not easy to surmount this, but maybe the example of the Voyagers will inspire us to allocate more resources towards the long-term.

Why NASA’s Interstellar Mission Almost Didn’t Happen

Launched 40 years ago, the Voyager space probes are on a grand tour of the cosmos that nearly ended at Saturn.

By Timothy Ferris.

This story appeared in the August, 2017 issue of National Geographic Magazine.

Insofar as we esteem the creations that last—Homer’s Odyssey, the bridge still standing, enduring love—let us now praise the twin Voyager space probes, launched 40 years ago and currently departing the solar system to drift forever among the stars.

Each about the size and weight of a subcompact automobile, the Voyagers epitomize 1970s high tech. Their computers are weaker than those in today’s digital watches, their analog TV cameras more primitive than the ones that shot Laverne & Shirley. But they made history at every planet they reconnoitered—confirming, as Voyager chief scientist Ed Stone put it, that “nature is much more inventive than our imaginations.”

Full article here:

http://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/2017/08/explore-space-voyager-spacecraft-turns-40/

To quote:

The Voyagers paved the way for the Jupiter orbiter Galileo and the Saturn orbiter Cassini that followed, which spent years gathering photos and data before being ordered to incinerate themselves in the planets’ upper atmospheres to ensure that they’d never impact and contaminate a possibly life-harboring moon. Now the Voyagers as well are nearing the end of their scientific life. Their weakening radio signals, currently reporting on the surprisingly complex plasma bubble that surrounds the sun and marks the designated boundary between the solar system and interstellar space, are expected to fall silent around 2030, when the Voyagers’ plutonium-powered electrical generators finally falter.

Thereafter the Voyagers will function more as time capsules than spaceships. With that eventuality in mind, JPL attached to each probe a copy of the “golden record” that contains music, photographs, and sounds of Earth for the benefit of any extraterrestrials who might intercept it someday. The records should remain playable for at least a billion years before succumbing to erosion from micrometeorites and the high-velocity subatomic particles called cosmic rays.

That’s a long time. A billion years ago, the most complex forms of life on Earth were the tidewater mats of cyanobacteria called stromatolites. A billion years from now, the brightening sun shall have begun boiling off Earth’s oceans. Yet the Voyagers will still be out there somewhere, emissaries of a species that dispatched them without hope of return.

The Voyagers have reached an anniversary worth celebrating

New documentary shows the human and scientific drama behind the iconic spacecraft.

ERIC BERGER – 8/7/2017, 7:15 AM

https://arstechnica.com/science/2017/08/the-voyagers-have-reached-an-anniversary-worth-celebrating/

Tipperary farm provided inspiration for hit space film

9:00 am – August 7, 2017

Caroline Allen

A farm outside Mullinahone, Co. Tipperary, sowed the seeds of a fascination that led to the making of a documentary on the Voyager space programme, which has been receiving rave reviews around the globe.

Emer Reynolds, director of the award-winning ‘The Farthest‘, told AgriLand how Mohober House’s night sky left her dazzled and “in awe of the visible smudge of our Milky Way galaxy overhead.”

Reynolds, an Emmy-nominated multi-award winning documentary director and feature film editor, is the force behind ‘The Farthest.’

Full article here:

http://www.agriland.ie/farming-news/tipperary-farm-provided-inspiration-for-hit-space-film/#

To quote:

A fascination with space began on those farm stays. “Mohober House’s sky at night was the opposite to the skies over our home in Dublin. We would drive to Tipperary in our old Hillman Hunter, my dad doing maths puzzles with us all the way, just for fun.

“As night fell, the dark, dark skies overhead would reveal the sparkling cosmos. I was dazzled and in awe of the visible smudge of our Milky Way Galaxy overhead.

I would spend hours lying on the grass, staring into the blackness. I was dreaming of tumbling through space, hurtling along at 67,000 mph, clutching onto a fragile blue planet.

“Aliens, horse-head nebula, star nurseries and time-travel, and exotic distant worlds filled my head as a child. They still do in fact.

“The film is a love story to that awe and wonder I first felt as a child in Tipperary,” Reynolds said.

http://theconversation.com/voyager-golden-records-40-years-later-real-audience-was-always-here-on-earth-79886

Voyager Golden Records 40 years later: Real audience was always here on Earth

August 13, 2017 10.33 pm EDT

Forty years ago, NASA launched Voyager I and II to explore the outer solar system. The twin spacecraft both visited Jupiter and Saturn; from there Voyager I explored the hazy moon Titan, while Voyager II became the first (and, to date, only) probe to explore Uranus and Neptune. Since they move too quickly and have too little propellant to stop themselves, both spacecraft are now on what NASA calls their Interstellar Mission, exploring the space between the stars as they head out into the galaxy.

Both craft carry Golden Records: 12-inch phonographic gold-plated copper records, along with needles and cartridges, all designed to last indefinitely in interstellar space. Inscribed on the records’ covers are instructions for their use and a sort of “map” designed to describe the Earth’s location in the galaxy in a way that extraterrestrials might understand.

The grooves of the records record both ordinary audio and 115 encoded images. A team led by astronomer Carl Sagan selected the contents, chosen to embody a message representative of all of humanity. They settled on elements such as audio greetings in 55 languages, the brain waves of “a young woman in love” (actually the project’s creative director Ann Druyan, days after falling in love with Carl Sagan), a wide-ranging selection of musical excerpts from Blind Willie Johnson to honkyoku, technical drawings and images of people from around the world, including Saan Hunters, city traffic and a nursing mother and child.

Since we still have not detected any alien life, we cannot know to what degree the records would be properly interpreted. Researchers still debate what forms such messages should take. For instance, should they include a star map identifying Earth? Should we focus on ourselves, or all life on Earth? Should we present ourselves as we are, or as comics artist Jack Kirby would have had it, as “the exuberant, self-confident super visions with which we’ve clothed ourselves since time immemorial”?

But the records serve a broader purpose than spreading the word that we’re here on our blue marble. After all, given the vast distances between the stars, it’s not realistic to expect an answer to these messages within many human lifetimes. So why send them and does their content even matter? Referring to earlier, similar efforts with the Pioneer spacecraft, Carl Sagan wrote, “the greater significance of the Pioneer 10 plaque is not as a message to out there; it is as a message to back here.” The real audience of these kinds of messages is not ET, but humanity.

In this light, 40 years’ hindsight shows the experiment to be quite a success, as they continue to inspire research and reflection.

Only two years after the launch of these messages to the stars, “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” imagined the success of similar efforts by (the fictional) Voyager VI. Since then, there have been Ph.D. theses written on the records’ content, investigations into the identity of the person heard laughing and successful crowdfunded efforts to reissue the records themselves for home playback.

The choice to include music has inspired introspection on the nature of music as a human endeavor, and what it would (or even could) mean to an alien species. If an ET even has ears, it’s still far from clear whether it would or could appreciate rhythm, tones, vocal inflection, verbal language or even art of any kind. As music scholars Nelson and Polansky put it, “By imagining an Other listening, we reflect back upon ourselves, and open our selves and cultures to new musics and understandings, other possibilities, different worlds.”

The records also represent humanity’s deliberate effort to put artifacts among the stars. Unlike everything on Earth, which is subject to erosion and all but inevitable destruction (from the sun’s eventual demise, if nothing else), the Golden Records are essentially eternal, a permanent time capsule of humanity. And unlike the Voyager spacecraft themselves – which were designed to have finite lifespans and whose journey into interstellar space was incidental to their primary function of exploring the outer planets – the Golden Records’ only purpose is to serve as ambassadors of humanity to the stars.

Placing artifacts in interstellar space thus makes the galaxy subject to the social studies, in addition to astronomy. The Golden Records mark our claim to interstellar space as part of our cultural landscape and heritage, and once the Voyager spacecraft themselves are not functional any longer, they will become proper achaeological objects. They are, in a sense, how we as a species have planted our flag of exploration in space. Anthropologist Michael Oman-Reagan muses, “Has NASA been to interstellar space because this spacecraft has? Have we, as a human species, [now] been to interstellar space?”

I would argue we have, and we are a better species for it. Like the Pioneer plaques and the Arecibo Message before them, the Golden Records inspire us to broaden our minds about what it means to be human; what we value as humans; and about our place and role in the cosmos by having us imagine what we might, or might not, have in common with any alien species our Voyagers eventually encounter on their very long journeys.

A nice gallery of Voyager mission images and current status updates:

http://newatlas.com/voyager-40th-anniversary-retrospective-gallery/50744/

“Ten spacecraft – from Venus Express to Voyager 2 – all tracked same solar flare”

The Register, 20170817

https://www.theregister.co.uk/2017/08/17/single_cme_onbserved_by_12_spacecraft/

No, a Map NASA Sent to Space Is Not Dangerous to Earth

http://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/08/nasa-map-not-dangerous-pulsars-aliens-earth-space-science/

Human ignorance is always the real danger.

Voyager: Inside humanity’s greatest space mission

In 1977, two spacecraft started a mission that has redefined our knowledge of the Solar System – and will soon become our ambassadors on a journey into the unknown. BBC Future looks at their legacy, 40 years after launch.

By Richard Hollingham

18 August 2017

http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20170818-voyager-inside-the-worlds-greatest-space-mission

To quote:

“I think it’s amazing when you look at what they put on in terms of American music,” says Stephanie Nelson, a professor at California State University in Los Angeles and a world music specialist. “It’s [mostly] black American music, which is pretty interesting.”

But the music was the least controversial aspect of the whole project. Voyager’s predecessors, Pioneer 10 and 11, famously had engraved plaques attached to their sides showing a naked man and woman. The Voyager team hoped to include an image of a nude couple on the golden disk.

“I felt it was an essential part of the nature of humanity,” says Lomberg, who spent days searching for a suitable image that was neither pornographic or overly clinical. He came up with one of a pregnant woman. “It seemed to us to be just right,” he says. “But Nasa was having none of it, they said, ‘No way!’

“Whenever I speak about it to an audience, it draws a derisive laugh,” says Lomberg. “It just seems so petty, so revealing of something about ourselves that’s slightly ridiculous.”

Emily Lakdawalla • August 17, 2017

Celebrating the 40th anniversaries of the Voyager launches

Sunday, August 20 marks the 40th anniversary of the launch of Voyager 2. Tuesday, September 5, will be the 40th anniversary for Voyager 1. Round anniversaries like these have no special significance for spacecraft that have departed Earth’s orbit; the significance is for those of us that the spaceships left behind on a planet that still revolves around the Sun once a year.

Anniversaries are a good time to look back and consider our past. Throughout the next three weeks, we’ll be posting new and classic material in honor of the Voyagers. Here’s a preview of that material; I’ll update this post with links as it’s published.

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2017/0817-celebrating-the-40th-anniversary-of-voyager.html

From the edge of the Solar System, Voyager probes are still talking to Australia after 40 years

August 18, 2017 1.03 am EDT

This month marks 40 years since NASA launched the two Voyager space probes on their mission to explore the outer planets of our Solar System, and Australia has been helping the US space agency keep track of the probes at every step of their epic journey.

CSIRO operates NASA’s tracking station in Canberra, a set of four radio telescopes, or dishes, known as the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex (CDSCC).

It’s one of three tracking stations spaced around the globe, which form the Deep Space Network. The other two are at Goldstone, in California, and Madrid, in Spain.

Between them they provide NASA, and other space exploration agencies, with continuous, two-way radio communication coverage to every part of the Solar System.

Four decades on and the Australian tracking station is now the only one with the right equipment and position to be able to communicate with both of the probes as they continue to push back the boundaries of deep space exploration.

Full article here:

http://theconversation.com/from-the-edge-of-the-solar-system-voyager-probes-are-still-talking-to-australia-after-40-years-82512

To quote:

Voyager 1 is still receiving commands that can only be sent from Canberra’s dishes. It is the only station with the high-power transmitter that can transmit a signal strong enough to be received by the spacecraft.

It has been an epic voyage for two spacecraft no bigger than small buses, two brilliant robots with an eight track tape deck to record data and 256 KB of memory.

How Nasa’s Voyager spacecraft changed the face of UK science

Although almost exclusively American, the 40-year-old Nasa Voyager spacecraft helped raise the ambitions of the UK’s planetary astronomers.

The rasp of the filling cabinet’s shutter fills the office, and my guest comes face to face with his past. “My pharaoh’s tomb is open,” he quips, before uttering a more heartfelt, “My goodness me.”

His name is Garry Hunt and we are standing in front of more than 80,000 postcard-sized photographs of the outer solar system. They were taken by a pair of Nasa spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2, that launched 40 years ago this summer.

Although Hunt now describes himself as a “golfer extraordinaire” back in the day he was an atmospheric physicist and the man responsible for the camera system that took these images.

He was the only senior British researcher associated with the mission. His success in that role not only helped change the way we saw Earth’s place in the universe, but also opened the way for the UK to become a global player in planetary exploration.

Full article here:

https://www.theguardian.com/science/across-the-universe/2017/aug/18/how-nasas-voyager-spacecraft-changed-the-face-of-uk-science

“It’s marvellous to think this archive is still here and still being used. Being involved so long ago – we started the mission 50 years ago – and this is still of interest … it’s exciting. This was a starting point and this information will be used time and time again,” says Hunt.

One thing that the photos can be used for is to compare them to more recent images. This way, scientists can look for changes in these worlds that hint at unseen processes taking place below their surfaces.

We are being hosted in this trip down memory lane by Carl Murray, professor of mathematics and astronomy at Queen Mary University of London, where the archive is located. Back in August 1977, when the first Voyager spacecraft was launched, he had just finished his bachelor’s degree and was working the summer as a porter at a hospital in Whitechapel.

He then headed out to Cornell University, New York, to start research using these images. He still returns to them today for inspiration of what to study next. “It is like holiday snaps but showing them to friends and saying well that’s really interesting, I think I’ll make my next holiday around that,” he says.

By holiday, he means “next space mission”.

We are all here to make a retrospective programme about the missions for the BBC World Service. And while Nasa have digital copies of these images in their computers back in the US, there is undoubtedly something special about seeing the only physical collections of these images in the world. It is like seeing the crown jewels of the mission.

…

The Voyagers are now heading out of our solar system, bound for the stars. Perhaps whimsically, each one carries a golden record that preserves sounds and images of Earth. They were the brainchild of Carl Sagan, who also worked at Cornell University. He reasoned that should extraterrestrials find the spacecraft floating in interstellar space, they would recognise the record as a way of us saying hello, and trying to tell them something about us.

“When I worked at Cornell,” says Murray, “I realised that a lot of the images on the record were taken around upstate New York [near the university]: the local supermarket and all these places I knew. So I had this fantasy that sometime in the future when the aliens pick up the Voyager spacecraft, learn how to read the disc and come back looking for all these locations and one day the aliens will land in upstate New York.”

New Documentary To Celebrate 40th Anniversary Of Voyager Spacecraft Launch

PBS and NASA are remembering the twin spacecraft four decades after their launch.

By Associated Press (Patch National Staff) – Updated August 18, 2017 6:58 pm ET

https://patch.com/us/across-america/new-documentary-celebrate-40th-anniversary-voyager-spacecraft-launch

To quote:

Ferris still believes it’s “a terrific record” and he has no “deep regrets” about the selections. Even the rejected tunes represented “beautiful materials.”

“It’s like handfuls of diamonds. If you’re concerned that you didn’t get the right handful or something, it’s probably a neurotic problem rather than anything to do with the diamonds,” Ferris told the AP earlier this week.

But he noted: “If I were going to start into regrets, I suppose not having Italian opera would be on that list.”

The whole record project cost $30,000 or $35,000, to the best of Ferris’ recollection.

NASA estimated the records would last 1 billion to 3 billion years or more — potentially outliving human civilization.

For Ferris, it’s time more than distance that makes the whole idea of finders-keepers so incomprehensible.

A billion years from now, “Voyager could be captured by an advanced civilization of beings that don’t exist yet … It’s literally imponderable what will happen to the Voyagers,” he said.

A bitcoin millionaire is sending his own time capsule into space on a CubeSat:

http://fortune.com/2017/08/19/taylor-swift-project-davinci-music-space/

Voyager’s Final Message – Update two years on.

Published on August 19, 2017

Andrew Millar

Founder of Swee

To mark the 40th anniversary of the Voyager space missions, filmmaker Christopher Riley announces the first results from his project to crowd source a final message for the memory banks of the twin Voyager space probes.

Two years on, a first analysis of the messages submitted in languages from all over the world has revealed that we are collectively hopeful for the future of humankind in the full knowledge of our many failings.

• Almost 20 times more people express feelings of hope than fear.

• Almost twice as many people reflect on peace than war.

• Thirteen times more people use the world love than hate.

• Twenty-five times more people write messages about friendship than enemies.

• Seven times more people write about life than death.

Christopher Riley launched the project on Facebook and on voyagersfinalmessage.com in 2015. He had first proposed the idea in his 2014 book for Haynes – the Voyager 1 & 2 Owners’ Workshop Manual: 1977 Onwards.

Christopher Riley says: “The beauty of asking people to write a short message which speaks for an entire planet is that it compels us to contemplate a bigger picture of what it means to be human. And that exercise still has the power to bring out the best in us.”

https://www.VoyagersFinalMessage.com has until the mid 2020s to gather as many short messages as possible, with the hope of persuading NASA to eventually select one of them for upload to each spacecraft before contact is lost, when onboard electrical power runs out.

Both Voyager 1 and 2 already carry a copy of a specially commissioned Golden Record, which contains music, greetings, sounds and even pictures encoded onto them, with the aim of communicating something of human culture to any extra-terrestrial civilization, which might one day encounter them.

Christopher Riley says: The original motivation for the Voyager Golden Record was to speak to the Cosmos with a single human voice. It was a chance to set our Earthly differences aside and to celebrate our collective humanity. What better time than now remind ourselves of that objective; by crowd sourcing a final message in that same spirit.”

The Facebook app celebrates the Voyager 1 and 2 space probes, and includes information about the Voyager missions, encouraging people to write their own ‘final message’ up to 1000 characters long (about the length of seven tweets). Each message submitted will automatically add the sender’s details to a petition database, which will be presented to NASA in the early 2020s.

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/voyagers-final-message-update-two-years-andrew-millar

The official Web site here:

https://www.voyagersfinalmessage.com/

Quoting from their main page:

If you could send such a message about humanity, to be read by an alien civilisation hundreds of millions of years from now, then what would you say?

The Voyagers are a long way from home right now and talking to them, even through NASA’s deep space communications network, is quite slow. So you need to keep your message pretty short; just 1000 characters, (about the length of seven tweets) – see the FAQs for more information.

Four Decades, Four Planets: Voyager 2 Celebrates 40 Years of Deep Space Exploration

By Ben Evans

http://www.americaspace.com/2017/08/20/four-decades-four-planets-voyager-2-celebrates-40-years-of-deep-space-exploration/

1911 – First around-the-world telegram sent, 66 years before Voyager II launch:

http://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/first-around-the-world-telegram-sent-66-years-before-voyager-ii-launch

How the Voyager Golden Record was Made

By Timothy Ferris

August 20, 2017

We inhabit a small planet orbiting a medium-sized star about two-thirds of the way out from the center of the Milky Way galaxy—around where Track 2 on an LP record might begin. In cosmic terms, we are tiny: were the galaxy the size of a typical LP, the sun and all its planets would fit inside an atom’s width. Yet there is something in us so expansive that, four decades ago, we made a time capsule full of music and photographs from Earth and flung it out into the universe. Indeed, we made two of them.

The time capsules, really a pair of phonograph records, were launched aboard the twin Voyager space probes in August and September of 1977. The craft spent thirteen years reconnoitering the sun’s outer planets, beaming back valuable data and images of incomparable beauty. In 2012, Voyager 1 became the first human-made object to leave the solar system, sailing through the doldrums where the stream of charged particles from our sun stalls against those of interstellar space.

Today, the probes are so distant that their radio signals, travelling at the speed of light, take more than fifteen hours to reach Earth. They arrive with a strength of under a millionth of a billionth of a watt, so weak that the three dish antennas of the Deep Space Network’s interplanetary tracking system (in California, Spain, and Australia) had to be enlarged to stay in touch with them.

Full article here:

http://www.newyorker.com/tech/elements/voyager-golden-record-40th-anniversary-timothy-ferris

To quote:

Rumors to the contrary, we did not strive to include the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun,” only to be disappointed when we couldn’t clear the rights. It’s not the Beatles’ strongest work, and the witticism of the title, if charming in the short run, seemed unlikely to remain funny for a billion years.

A Reverie for the Voyager Probes, Humanity’s Calling Cards

Dennis Overbye

OUT THERE AUG. 21, 2017

In the shadow, one might say, of the Great American Eclipse, a major anniversary in the history of space exploration — and indeed cosmic consciousness — is being celebrated.

It was 40 years ago, on Aug. 20 and Sept. 5, 1977, that a pair of robots named Voyager were dispatched to explore the outer solar system and the vast darkness beyond.

What resulted was nothing less than a reimagining of what a world might be and what strange cribs of geology and chemistry might give rise to life in some form or other.

It was a real-life Star Trek adventure, but the crew stayed home, communicating with their two spacecraft through a billion-mile bucket brigade of data bits.

New computer programs went one way, and data — including scratchy photos of new landscapes and the whispering moans of interplanetary plasma fields — came back the other way. All of it was being carried out by a robot brain with the memory capacity of an old-fashioned digital watch.

Full article here:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/21/science/voyager-nasa-40th-anniversary.html

To quote:

Voyager 1 was in interstellar space, the first human artifact to escape the solar system. It and its twin will go on circling the galaxy, long after it has ceased speaking to us.

In the fullness of galactic time, the Voyagers may be found, but by then the human race may be long extinct. The Voyager record might be the only physical remnant, the last lonely evidence that we, too, once lived in this city of stars, among these islands of ice and rock.

Back then, we were looking forward to an exploration of space that would go on forever. It was magic, and we were all on the spaceship.

Post Solar Eclipse, NASA Celebrates 40 Years Since ‘The Golden Record’

8/21/2017 by Adrienne Gaffney

Forty years ago, the space probe Voyager 2 took off to study the outer reaches of the solar system with a very significant piece of US culture inside. The Golden Record, a 12-inch gold-plated phonograph recording, was created by a committee chaired by famed astronomer Carl Sagan, as a way of communicating to extraterrestrials about what life on Earth is like.

Recordings on it included greetings in several languages, natural sounds, a message from President Carter and selections from Beethoven, Mozart and Bach, as well as the Chuck Berry classic “Johnny B. Goode.” In 2017, as the Voyager 2 and its companion Voyager 1 continue to explore space, interest in the Golden Record is greater than ever.

A PBS documentary The Farthest – Voyager in Space airing on August 23 explores its creation, while the record itself is now available to purchase as a vinyl box set after a Kickstarter campaign brought in almost $1.4 million.

Full article here:

http://www.billboard.com/articles/news/lifestyle/7934261/post-solar-eclipse-nasa-celebrates-the-golden-record

To quote:

Nick Sagan, the son of Carl, was seven at the time of the recording and was asked to provide a greeting. “They came to me and said, ‘hey, Nick, do you have a message you wanted to leave for extraterrestrials? What would it be?’ I just thought about it and said, ‘Hello, from the children of planet Earth,’” he tells Billboard. “Looking back, it’s a strange feeling to know that there is some piece of your self that is the most distant human-made object in the universe and that’s going to survive long, long after everything.”

The continued fascination in the work of Sagan, who passed away in 1996, has been incredibly gratifying to Nick, who was interviewed for The Farthest and also helped with the Kickstarter efforts. “He’s more present in his absence than a lot of people are in their presence and his work. His scientific work and his understanding of what the stakes are and care for our planet and where we’re going and how to reel us in from our biggest possible mistakes, he did such amazing work at the time that still inspires people to this day,” he says.

…

Selecting the musical elements to include was a tremendous undertaking. Ferris was very focused on making such a wide breadth of cultures were represented which meant scouring record stores to find world tracks that were obscure at that time. Ferris wanted to include on rock song and science writer Ann Druyan, creative director of the project and Sagan’s future wife, suggested “Johnny B. Goode,” which was far from an easy sell to the rest of the committee.

“This seems much less controversial today than it was at the time,” Ferris explains. “Carl himself didn’t like Chuck Berry. The first time he heard the track he had no experience with rock. He and I used to listen mostly to classical. I would occasionally play him a rock track and he was interested but he hadn’t gotten into it. Alan Lomax the folklorist we worked with, he was opposed to Chuck Berry. But it turned out to be a popular choice.”

The primary goal of the Golden Record was to create something that could offer to any unknown being that encountered it a sense of what human life is like. But to Ferris, whether it has or ever will be discovered is far from the point. “I’ll never know, but I think that’s part of the beauty of the record. It would be appreciated by anyone finding the record in the future regardless of how different from humans they may be,” he says. “The record, in itself, says we realize that we will probably never know what happens to this record and we did it any way. There’s something beautiful about that.”

Ted Stryk • August 23, 2017

Voyager 40th anniversary: The transformation of the solar system

Earlier this summer, on the second anniversary of the New Horizons Pluto flyby, I tweeted that “Pluto became a real place, and we will never see the solar system the same way.” New Horizons was and is a capstone mission, exploring the final major world that humanity set out to explore at the dawn of the space age and is now on its way to making the first close-up observations of an object in the solar system beyond.

Much was made of the Pluto encounter occurring fifty years after Mariner 4 began humanity’s quest to see the solar system beyond the Earth-Moon system with remote eyes, the reconnaissance of the solar system known at the outset was complete.

Of the eight planets that received their visits of the first time, four of them – half – were transformed by one mission, as were the overwhelming majority of moons. Consisting of two spacecraft, the Voyagers brought into focus more planetary real estate (or at least cloud estate) than all other missions combined. I am of course aware that Pioneers 10 and 11 were the first to Jupiter and Saturn, but despite my fondness for these missions, they carried no real camera, merely a scanning photometer, that, while showing us fascinating unearthly angles, did not upend our conception of either planet or their moons. While their particle and fields instruments provided a wealth of discoveries, gaining a feeling of what it is like to be in their presence was left to the Voyagers.

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2017/voyager-40th-anniversary-the.html

Neil deGrasse Tyson and Carolyn Porco on Voyager and Space Exploration by Science at AMNH

https://soundcloud.com/amnh/neil-degrasse-tyson-and-carolyn-porco-on-voyager-and-space-exploration

From Voyager to Wormholes…

https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/nee4nm/how-humans-will-finally-reach-interstellar-space

Emily Lakdawalla • August 25, 2017

Voyager 40th anniversary: The Planetary Report’s chronicles

The Planetary Society came into being at the same time that the Voyagers began their grand tour of the outer solar system. Except for the Voyager missions, the 1980s were a grim period for planetary exploration. Consequently, the first decade of our member magazine, The Planetary Report, was dominated by Voyager coverage alongside reporting on the Russian missions to Mars and editorials about the future of planetary exploration.

Before the spread of the Internet, this magazine was how many space enthusiasts got any news about the Voyager missions beyond newspaper articles and television. As it still does today, The Planetary Report features the voices and perspectives of the scientists, engineers, and managers directly involved in the missions. In honor of the 40th anniversary of the Voyager missions, we’re making publicly available seven back issues of The Planetary Report, featuring writing from Planetary Society founder Carl Sagan alongside numerous scientists and engineers from the Voyager mission: Ellis Miner, Torrance Johnson, William McLaughlin, David Morrison, Jeff Cuzzi, Bob Brown, Norman Ness, Carolyn Porco, Garry Hunt, David Stevenson, and more.

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/emily-lakdawalla/2017/0825-voyager-40th-anniversary-the.html

Don’t forget the probe that paved the way for Voyager and all the others…

http://galacticjourney.org/august-27-1962-bound-for-lucifer-the-flight-of-mariner-2/

Voyager Made the Solar System a Real Place

Forty years later, a mission scientist remembers a time of constant discovery.

MARINA KOREN

AUG 25, 2017

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/08/voyager-anniversary/537819/?utm_source=feed

To quote:

Porco remembers fondly the peak of the Voyager mission, when it felt like scientists and engineers were learning something new every day. Engineers would gather around monitors at JPL and stare at the latest images, or pass around hard copies. Eventually, they’d gather their thoughts and give press conferences, where the photos would be shown and shared with journalists. “The public didn’t see those images until they were either shown on television or they were printed in magazines or newspapers,” Porco said.

Today, images of other planets in the solar system are uploaded online soon after the data returns to Earth, where they can be viewed by millions of people. The immediate dissemination of these photographs is a good thing, Porco said, but she misses the camaraderie that permeated JPL during the Voyager days. Porco leads the imaging team of the Cassini mission around Saturn, and doesn’t receive new images in a room full of people. “Images would come down, I’d be sitting in my office all alone,” she said.

That’s the thing about uncovering new worlds—you can only do it once. While Cassini provides dazzling views of Saturn, far better than anything the Voyager mission could have sent back, the photographs don’t shock as they did 40 years ago. The thrill of discovery isn’t quite the same.

“It’ll never happen like this again because we’ve been to all the planets and we’ve been to comets,” Porco said. “We’ve been all over the solar system now. We’ll never again have the kind of encounters that we had with Voyager, because we know too much now.”

Ian Regan • August 28, 2017

Voyager 40th Anniversary: Watching an Alien World Turn

In 1979, two robotic emissaries, conceived of and built by humans, trained their electronic eyes upon a giant alien planet and its coterie of moons. The images radioed back to Earth by these now iconic spacecraft have been printed and reprinted throughout the 38 years since. But due to limited processing power, the quality of the original data was never fully conveyed in the color composites that flashed up in newscasts, adorned glossy pages in magazines, and hung as posters in the bedrooms of space-obsessed youngsters with starry-eyed ambitions. Few people (except, maybe, regular readers of this website) know that all the original data are available to the public, just waiting to be reworked with modern image processing techniques.

In this context, I set my goal to restore the time-lapse movies that both Voyager space probes captured as they edged closer to rendezvous with Jupiter in 1979. In these breathtaking sequences, the giant world rotates before us. Cloud bands and the famous Great Red Spot appear from the gloom, only to swiftly disappear over the horizon. The satellites first spotted by Marius and Galileo whip around in a Newtonian dance, casting fuzzy shadows upon the cloud decks.

The Voyager 1 movie may be familiar to most watchers of science documentaries, but it has not before been seen in a high-definition, high-fidelity format of quality matching the source data.

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2017/0828-watching-an-alien-world-turn.html

http://www.syfy.com/syfywire/we-could-be-sending-aliens-a-new-digital-message

WE COULD BE SENDING ALIENS A NEW DIGITAL MESSAGE

Contributed by

Elizabeth Rayne

hen Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 took off in 1977, they both left Earth’s atmosphere carrying a message otherwise known as the Golden Record to hypothetical aliens. Now that Voyager 1 is floating in interstellar space, with its twin to follow in several years, we need to send another message—on another satellite.

The “Golden Record” was designed to teach any E.T.’s who may have not phoned home yet a crash course on Earth and Earthlings. Recorded onto each record were photos, music, sounds and other data the Voyager team envisioned it someday reaching an intelligent civilization that exists light-years away. The next satellite soon headed beyond our solar system is New Horizons, and scientists don’t want to slip through their fingers without carrying some sort of message to tell anyone out there that we’re out here.

“[New Horizons] is leaving without a Golden Record, without a message,” said Jon Lomberg, design director for the Voyagers’ Golden Record who collaborated with the committee chair, none other than Carl Sagan. “That seems like a missed opportunity.”

Enter Golden Record 2.0 aka One Earth Message.

http://oneearthmessage.org/

One Earth Message is a digital version of the Golden Record that will be crowdsourced (don’t look at NASA for funding here) for the $75,000 it will need to be transmitted to New Horizons in 2020.

Since August 20 marked the 40-year anniversary of the Voyager launch, it was then that Lomberg and his team got a Kickstarter campaign ready for liftoff. Why so expensive? There needs to be a website built for photos and any other material people send in as potential facets of the One Earth Message, and a website crawling with frequent digital submissions of what we think aliens should know about our planet must be managed and maintained. Assuming there are no glitches, voting will determine what will ultimately get beamed to New Horizons.

New Horizons recently whizzed past Pluto and is en route to object 2014 MU69. Transmitting all the data it collects on this object will take about a year, clearing enough memory to upload the One Earth Message. Lomberg is optimistic this timeframe is enough to pull it off, but he will still need NASA approval. Chances for that are astronomically higher when you present a finished product.

Lomberg sees far past New Horizons when it comes to sending messages into space. He sees a future in which every probe that eventually goes interstellar traverses the universe with a message onboard.

“We will never know if there is an E.T. audience, but for the human audience that participates, it can be a profoundly moving experience to seriously contemplate communicating with the cosmos,” he said.

Whether the aliens (if they exist) will even recognize the message as a method of communication and not an expertly disguised nuclear weapon is an entirely different issue.

(via Space.com)

Björn Jónsson • August 30, 2017

Voyager 40th anniversary: Revisiting the Voyagers’ planetary views

I would argue that the Voyager mission is the most successful planetary mission of all time. Even now, 40 years after Voyager 1 and 2 were launched, a lot of the data they returned is still of high interest. In some cases it is obvious why: After all these years Voyager 2 is still the only spacecraft that has visited Uranus and Neptune.

The Voyager Jupiter data is also still very interesting, even though other spacecraft have followed in Voyager’s footsteps. This is because the Voyager data, from 1979, allows us to monitor the long-term behavior of Jupiter and Io, and also because the Galileo mission that followed the Voyagers and orbited Jupiter in 1995-2003 was only partially successful due to the failure of its high gain antenna. Cassini flew by Jupiter en route to Saturn in 2000, but came no closer to Jupiter than about 10 million kilometers. Recently the Juno spacecraft has been orbiting Jupiter, but its scientific goals are different from Voyager and Galileo and in many ways complementary to them.

Voyager’s Saturn data is perhaps the least interesting data set (surpassed by data from the spectacularly successful and long-lived Cassini mission), but still of interest for monitoring long-term changes in Saturn’s and Titan’s atmospheres and for studying Saturn’s magnetosphere.

So processing (and reprocessing) the Voyager imaging data is still highly rewarding. Amateur space image processors and citizen scientists have produced many spectacular images from the raw Voyager image data set. Below is a selection of Voyager images from all four planets the Voyagers flew by. I did not always select the most spectacular or beautiful images. Instead I selected images to show various features and examples of the Voyager imaging coverage.

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2017/0830-voyager-40th-anniversary-bjorn.html

Celebrating Voyager 40 at the AMNH:

http://mashable.com/2017/08/31/voyager-40th-anniversary-golden-record-neil-degrasse-tyson-the-farthest/#bLO1j6wTbaqt

http://www.iberkshires.com/story/55493/Williams-College-Astronomer-s-Photo-Has-Left-the-Solar-System.html

Williams College Astronomer’s Photo Has Left the Solar System

10:44 AM / Sunday, September 03, 2017

WILLIAMSTOWN, Mass. — NASA is celebrating the 40th anniversary of two spacecraft, Voyager 1 and 2, that were launched toward Jupiter and Saturn, which they reached in 1979 and 1980, respectively. Voyager 2 went on to Uranus and Neptune, passing Neptune in 1989. Since then, they have continued outward, one even leaving the solar system.

Each of the Voyagers contains a golden record that contains 115 photographs, greetings in many languages, and samples of music from Bach to Chuck Berry. The images are encoded in analog form.

One of the photographs was taken by Williams College astronomer Jay Pasachoff.

“Carl Sagan had the idea for the golden record, and our then-recent Williams College alumna Wendy Gradison was assisting him,” Pasachoff said. “I submitted a few photographs on various topics, and two were chosen. The picture that was ultimately launched, in digital form, was taken from a helicopter on my honeymoon. We were approaching Heron Island in the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, and the photo is in a geology sequence since it shows the reef, trees, ocean, beach and other terrestrial features.

“I get requests periodically for my copyright permission to use the photo, most recently for a Kickstarter campaign that has succeeded in making a facsimile edition to mark the anniversary,” he said.

A second photo, showing the birth of his first child, did not make the final cut. NASA selected a line drawing instead.

The Heron Island photograph appears on the official Voyager website of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and is the quadruple-sized image at the right side of the sixth and seventh row. (View them here.) Messages from President Jimmy Carter and from the UN Secretary-General also appear.

Why the golden record? While Sagan thought it was actually to make citizens of Earth reflect on our common humanity, it has been phrased as something for aliens to perhaps pick up one day.

“If they are smart enough to find the spacecraft,” Pasachoff said, “they will be smart enough to figure out how to play the record.” As Sagan said, “The spacecraft will be encountered and the record played only if there are advanced spacefaring civilizations in interstellar space.”

“Not only is it fun to have a photo I took leave the solar system, but also I am proud that on listings of the photos the image two down from mine is by Ansel Adams, perhaps the best nature photographer of all time,” Pasachoff said.

The Voyagers are now over 100 times farther from the Sun than our Earth is, with their radio signals taking over 17 hours to reach us. Voyager 1 was launched on September 5, 1977. Voyager 2 was launched 16 days earlier, but on a slower trajectory, so reached Jupiter slightly after Voyager 1.

http://gantdaily.com/2017/09/04/voyagers-golden-record-still-plays-on/

Voyager’s Golden Record still plays on

Posted on Monday, September 4, 2017 by CNN in Opinion

Forty years ago this week, NASA launched the second of two Voyager spacecraft on a grand tour of the solar system and into the mysteries of interstellar space. It was an audacious mission that continues to this day — as the probes launched in 1977 still call home with new data about the cosmos.

Attached to each of these spacecraft is a beautiful golden phonograph record containing a message for any extraterrestrial intelligence that might encounter it, perhaps billions of years from now. This enchanting artifact, officially called the Voyager Interstellar Record, may be the last vestige of our civilization after we are gone forever.

Right now, Voyager 1 is almost 21 billion kilometers away from us in interstellar space, barreling along at 17 kilometers per second. It is the farthest human-made object from Earth. The slightly slower Voyager 2 is at the outermost edge of our solar system, where the sun’s plasma wind blows against cosmic dust and gas. Even at such astonishing distances, those shiny gold records affixed to their hulls have incredible resonance way back here on Earth. Why?

Compiled in just a few months by a dynamic committee led by Carl Sagan, the golden record is both an inspired scientific effort and a compelling piece of conceptual art.

“The launching of this ‘bottle’ into the cosmic ‘ocean’ says something very hopeful about life on this planet,” Sagan wrote in “Pale Blue Dot.”

Indeed, the Voyager Golden Record is a reminder of what we can achieve when we are at our best, and that our future really is up to all of us.

It’s a story of our planet expressed in sounds, images, and science: Earth’s greatest music from myriad peoples and eras, from Bach and Blind Willie Johnson to Benin percussion to Solomon Island panpipes. Natural sounds — birds, a train, a baby’s cry, a kiss — are collaged into a lovely audio poem called “Sounds of Earth.” There are spoken greetings in dozens of human languages— and one whale language — and more than 100 images encoded in analog that depict who, and what, we are. A diagram on the aluminum cover of the record explains how to play it and where it came from.

As an objet d’art and design, the Voyager Record represents deep insights about communication, context, and the power of media. In the realm of science, it raises fundamental questions about our place in the universe.

Two years ago, my friends Timothy Daly, Lawrence Azerrad, and I embarked on a journey to release the Voyager Record to the public on vinyl for the first time. We launched a Kickstarter to crowdfund our effort through pre-orders of a lavish box set containing three translucent gold LPs, a book, and an art print. The response was astounding. More than 10,000 people pledged their support, including many who told us they don’t even own a record player. The “Voyager Golden Record: 40th Anniversary Edition” became the most funded music project in Kickstarter’s history. We donated 20% of the net profits from that limited Kickstarter edition to the Carl Sagan Institute at Cornell University.

It isn’t that the Voyager Record seduces us with a nostalgia trip to an era of wide-eyed optimism. In fact, the record is perhaps more relevant now than when the two spacecraft launched back in 1977. As the original golden record’s producer, Timothy Ferris, wrote in the liner notes for our project, the Voyagers are on a journey not just through space but also through time. The record is a time capsule but it is also timeless. It sparks the imagination. It provokes us to think about the future and our civilization’s place in it. It exudes a sense of hope for a better tomorrow.

Listen here to an audio sampler of the Voyager Golden Record

When astronomer and technical director Frank Drake, designer Jon Lomberg, and their colleagues set about curating the images to encode in the record’s grooves, they agreed from the outset to avoid depictions of war, crime, poverty and disease. It was a conscious decision that the interstellar message could reflect only positively on our planet. The golden record’s photo sequence is a visual time capsule of Earth. It’s a snapshot of life on our planet, and an aspirational one at that. Similarly, the greetings in Earth’s most widely spoken languages are words of peace and goodwill.