I’m going to miss the Cassini mission as much as anyone, but I have to say it’s fascinating to watch how mission controllers are wringing good science out of every last moment of the spacecraft’s life. We’re now in the Grand Finale phase of the mission, in which Cassini has moved between the planet and its rings in a series of weekly dives. Now we’re about to push into a new series of close passes, actually moving through Saturn’s upper atmosphere.

Notice the language that Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, uses to describe what’s next:

“As it makes these five dips into Saturn, followed by its final plunge, Cassini will become the first Saturn atmospheric probe. It’s long been a goal in planetary exploration to send a dedicated probe into the atmosphere of Saturn, and we’re laying the groundwork for future exploration with this first foray.”

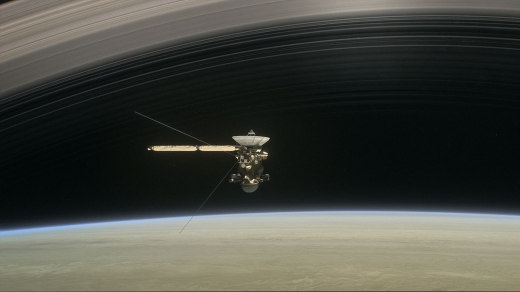

Image: This artist’s rendering shows Cassini as the spacecraft makes one of its final five dives through Saturn’s upper atmosphere in August and September 2017. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Cassini as atmospheric probe? The mind boggles, but this will not be the first time the spacecraft has had to deal with an atmosphere. Those close flybys of Titan that produced so many spectacular findings about its atmosphere and surface required Cassini to use its rocket thrusters to maintain stability. You could consider the Titan flybys advanced preparation for this culminating act, and one in which the thrusters are being given wide margins for safety.

Consider the first atmospheric pass at Saturn, which will occur at 0022 EDT (0422 UTC) on Monday, August 14. The point of closest approach during these passes is to be between 1630 and 1710 kilometers above Saturn’s cloud tops. The built in margin is this: The thrusters are expected to operate somewhere between 10 and 60 percent of their capacity, the exact figure being determined by how stable the spacecraft remains through the procedure.

Anything beyond 60 percent means it proved harder to maintain stability than anticipated, a problem that would be corrected by a so-called ‘pop-up maneuver’ that will use the thrusters to increase the altitude of the later closest approaches by about 200 kilometers. Conversely, if no such maneuver is required, the orbit could be lowered as much as 200 kilometers on the last two orbits. In any case, a final ‘pop-down maneuver’ will occur on September 11, bending Cassini’s orbit (with the help of Titan) for the final plunge into the planet on September 15.

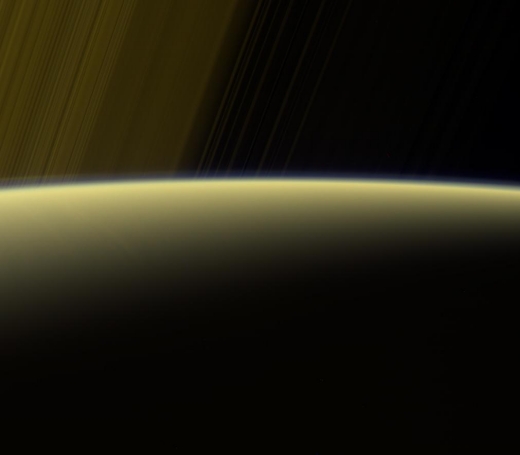

Image: This view from Cassini shows the narrow band of Saturn’s atmosphere, which Cassini will dive through five times before making its final plunge into the planet on Sept. 15. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

For now, we’ll be collecting data from Cassini’s ion and neutral mass spectrometer (INMS) to examine Saturn’s atmosphere, with other instruments producing high-resolution data on the planet’s auroras, atmospheric conditions and the vortices at the planet’s poles. Radar examination through the atmosphere should render features as small as 25 kilometers wide, about 100 times smaller than we’ve been able to obtain before the Grand Finale phase.

Cassini’s end on September 15 should be abrupt. With all seven of its science instruments reporting, the spacecraft will quickly reach an atmospheric density about twice what it should encounter during these final five passes. At that point, with the thrusters no longer able to maintain stability, Cassini’s antenna will lose its lock on Earth and we will lose contact.

Thinking about all that Cassini has given us, that’s a hard end to consider. But the spacecraft will be working until the last, augmenting the vast data flow we’ve received from Saturn. The discoveries we extract from Cassini’s mission will continue long after the probe is gone.

Don’t go gently into that good night.

We did this with Venus Express. You can learn a lot about an upper atmosphere if you’re willing to sacrifice a spacecraft.

Also: wouldn’t it be “funny” if we ended up accidentally seeding a cloud-based biosphere on Saturn? So much for planetary protection…

I hope any microbes onboard hunker down behind some heat resistance materials survive entry, multiply profusely and their descendants evolve into a space faring species that comes back to Earth to give the spacecraft team who tried to end their existence bad guts !

Rant over !

Planetary protection indeed! Good point, David.

If no life is there there is no need for planetary protection.

Some spiders make a balloon from the thread, lets seed Saturn with spiders to keep your ‘biosphere’ under control.

This will soon go out of control, and Saturn will soon be big spider cocoon! ;)

If the Venus Express probe had microbes in or on it and some of the probe survived they may have found the clouds of Venus a very nice habitat.

They would have to survive the orbiter burning up in Venus’ atmosphere.

Of the 12 proposals for New Frontier missions, one of them is a Saturn atmosphere probe called the Saturn PRobe Interior and aTmosphere Explorer (SPRITE). Other plans call for robot explorers to Enceladus and Titan.

The details are here:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/van-kane/20170810-new-frontiers-missions.html

Would Cassini soon have become unusable for further planetary science? And if so, for what reason? Or did NASA choose to willingly sacrifice Cassini?

Cassini is running out of propellant. NASA is simply trying to get as much good science out of the mission as possible in its final days.

As well as where Cassini finally ends up. Which means not into Enceladus or Titan, so that any potential life on those moons is not contaminated by Earth life.

It’s possible that we’ve already done that with Venus unintentionally, via the Pioneer Venus 1 Orbiter and the Pioneer Venus 2 Multiprobe (also designated Pioneer 12 and 13, respectively) spacecraft, as well as the Soviet Venera and VEGA spacecraft. Also:

The drum-shaped Pioneer 13 Multiprobe bus, which carried four atmospheric entry probes (a single large one and three small ones) to Venus, was also equipped with atmospheric instrumentation (an ion mass spectrometer and a neutral mass spectrometer), even though–like Cassini–it wasn’t designed to survive entry into a planetary atmosphere, and:

The bus continued transmitting data until it burned up, somewhat deeper in the Cytherean atmosphere (about 110 km altitude) than was expected; it provided the only direct measurements of that zone of the upper atmosphere, because the four entry probes didn’t begin collecting and transmitting data until they passed through the “meteoric” phase of descent. Hopefully, Cassini will pleasantly surprise us as Pioneer 13’s bus did. (If Cassini could be pre-programmed to switch to its low-gain antenna when the thrusters could no longer hold the spacecraft steady as it plunges deeper into Saturn’s atmosphere, we might–if the Arecibo or the Very Large Array radio telescopes could “listen in”–be able to get somewhat more in situ atmospheric data before it burns up.)

With the type of microbes that might have taken a ride with the probes sent to survive a landing on Venus, intentionally or otherwise, I have trouble imagining they would survive on the surface of that planet for very long. 900 degrees Fahrenheit on average everywhere (in fact it is even warmer at the poles!), 90 times Earth atmosphere crushing down on the surface, and sulfuric acid permeating the air. If a terrestrial creature can survive that, then they deserve to live.

Now they might be able to survive under the surface as I have seen speculated, but that means they would somehow have to get from the lander to several meters underground without being destroyed in the process. Other microbes might have gotten off in the upper atmosphere of Venus where the climate is much more Earth-like. Those two Soviet Vega balloons from 1985 floated about for almost two Earth days. Also most of the landers sent to Venus drifted in the planet’s air for many minutes, so maybe a few hitch-hikers escaped. We won’t know until we send a dedicated atmosphere mission there that can last for months or more.

Aerial life was what I was thinking about regarding the ESA, Soviet, and U.S. (and now, Japanese) Venus probes. While the VEGA balloons gave the greatest chances for any “hitch-hiking” microbes to be released into the atmosphere, the other spacecraft–as they either entered intact or broke up, depending on what kinds of vehicles they were–could possibly have “harbored and released” terrestrial micro-organisms into the air at cool enough altitudes to enable at least some of them to survive, even with updrafts and downdrafts into more hostile zones.

So let us send some atmosphere-floating probes to Venus to find out.

Meanwhile, speaking of Venus probes:

http://spectrum.ieee.org/automaton/robotics/space-robots/jpl-design-for-a-clockwork-rover-to-explore-venus

Whoa–I like the idea of a clockwork, largely-mechanical Venus rover (the landsail one in an accompanying article on that page is also interesting, as is the NASA HAVOC *manned* Venus expedition article on there)! I also couldn’t resist reading the new article (which includes a video of a working replica) on that page about the highly-sophisticated ancient Greek mechanical astronomical computer that was salvaged from the Antikythera wreck in 1900 (see: http://www.washingtonpost.com/news/speaking-of-science/wp/2016/06/14/the-worlds-oldest-computer-is-still-revealing-its-secrets/?utm_term=.5383ec2d2dab ); it makes Carl Sagan’s fantasy (in “Cosmos”) about the Ionian Greeks–had science continued–possibly building starships by now seem like ^more^ than pure fantasy…

https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.05036

Astronomical Observability of the Cassini Entry into Saturn

Ralph Lorenz

(Submitted on 16 Aug 2017)

The Cassini spacecraft will enter Saturn’s atmosphere on 15th September 2017. This event may be visible from Earth as a ‘meteor’ flash, and entry dynamics simulations and results from observation of spacecraft entries at Earth are summarized to develop expectations for astronomical observability.

Comments: 10 pages, 2 figures, 2 tables

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:1708.05036 [astro-ph.EP]

(or arXiv:1708.05036v1 [astro-ph.EP] for this version)

Submission history

From: Ralph Lorenz [view email]

[v1] Wed, 16 Aug 2017 18:49:21 GMT (110kb)

https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1708/1708.05036.pdf

Mariner 9 is also expected to perform its “swan song dive” before too much longer (2022), when it will enter Mars’ atmosphere and create a luminous meteoric trail. If Cassini’s burn-in at Saturn can be observed from Earth, Mariner 9’s fiery demise–especially if it occurs (even partly) over the night side (or even over a limb) of Mars–should also be observable from Earth.

Mariner 9 should be rescued and placed in a museum, even if it is one in space.

JPL NASA NEWS | AUGUST 24, 2017

NASA Announces Cassini End-of-Mission Activities

https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=6930