The Jet Propulsion Laboratory has just published details about Cassini’s last days and its final plunge into Saturn on September 15. That last act turns the craft into our first planetary probe of Saturn, to use Linda Spilker’s memorable phrase. A Cassini project scientist at JPL, Spilker goes on to note that the probe will be “sampling Saturn’s atmosphere up until the last second. We’ll be sending data in near real time as we rush headlong into the atmosphere — it’s truly a first-of-its-kind event at Saturn.”

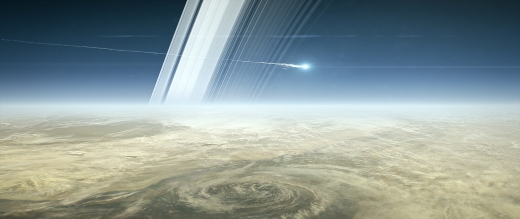

Image: Cassini streaks across Saturn’s sky in its final moments. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

I want to lift the Cassini final calendar out of this JPL news release, as many Centauri Dreams readers have expressed an interest particularly in the mission-ending atmospheric entry. We will likely lose radio contact within, JPL estimates, one to two minutes after the descent into the atmosphere begins. Eight of the twelve science instruments will be operating throughout the plunge, including the ion and neutral mass spectrometer (INMS), which will be sampling Saturn’s atmosphere. The imaging camera will be off during the descent.

The predicted time for loss of signal on Earth is 0754 EDT (1154 UTC) on September 15. JPL’s End of Mission Timeline is up and running, with a countdown clock and full schedule of events. The schedule below will probably be tweaked as we get closer to the final day, so keep checking the Timeline page as well as @CassiniSaturn on Twitter for updates.

Did you miss today’s preview of our #GrandFinale at Saturn? Catch the replay at: https://t.co/5adt2ODbgo pic.twitter.com/hFnqzg6miP

— CassiniSaturn (@CassiniSaturn) August 29, 2017

Here’s the schedule as it stands this morning:

- Sept. 9 Cassini will make the last of 22 passes between Saturn itself and its rings — closest approach is 1,044 miles (1,680 kilometers) above the clouds tops.

- Sept. 11 — Cassini will make a distant flyby of Saturn’s largest moon, Titan. Even though the spacecraft will be 73,974 miles (119,049 kilometers) away, the gravitational influence of the moon will slow down the spacecraft slightly as it speeds past. A few days later, instead of passing through the outermost fringes of Saturn’s atmosphere, Cassini will dive in too deep to survive the friction and heating.

- Sept. 14 — Cassini’s imaging cameras take their last look around the Saturn system, sending back pictures of moons Titan and Enceladus, the hexagon-shaped jet stream around the planet’s north pole, and features in the rings.

- Sept. 14 (5:45 p.m. EDT / 2:45 p.m. PDT) — Cassini turns its antenna to point at Earth, begins a communications link that will continue until end of mission, and sends back its final images and other data collected along the way.

- Sept. 15 (4:37 a.m. EDT / 1:37 a.m. PDT) — The “final plunge” begins. The spacecraft starts a 5-minute roll to position INMS for optimal sampling of the atmosphere, transmitting data in near real time from now to end of mission.

- Sept. 15 (7:53 a.m. EDT / 4:53 a.m. PDT) — Cassini enters Saturn’s atmosphere. Its thrusters fire at 10 percent of their capacity to maintain directional stability, enabling the spacecraft’s high-gain antenna to remain pointed at Earth and allowing continued transmission of data.

- Sept. 15 (7:54 a.m. EDT / 4:54 a.m. PDT) — Cassini’s thrusters are at 100 percent of capacity. Atmospheric forces overwhelm the thrusters’ capacity to maintain control of the spacecraft’s orientation, and the high-gain antenna loses its lock on Earth. At this moment, expected to occur about 940 miles (1,510 kilometers) above Saturn’s cloud tops, communication from the spacecraft will cease, and Cassini’s mission of exploration will have concluded. The spacecraft will break up like a meteor moments later.

By the JPL countdown clock, it’s just under 16 days to final signal received on Earth as I write this. It’s worth quoting Cassini project manager Earl Maize at this point:

“The end of Cassini’s mission will be a poignant moment, but a fitting and very necessary completion of an astonishing journey. The Grand Finale represents the culmination of a seven-year plan to use the spacecraft’s remaining resources in the most scientifically productive way possible. By safely disposing of the spacecraft in Saturn’s atmosphere, we avoid any possibility Cassini could impact one of Saturn’s moons somewhere down the road, keeping them pristine for future exploration.”

Cassini doesn’t have HAL’s AI smarts, but I keep thinking about the final burn Arthur C. Clarke’s famous computer gave to the Discovery in the film 2010: The Year We Make Contact. ‘Poignant’ only begins to explore the complex emotions I’m feeling as we prepare to lose this bird.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.05036

Astronomical Observability of the Cassini Entry into Saturn

Ralph Lorenz

(Submitted on 16 Aug 2017)

The Cassini spacecraft will enter Saturn’s atmosphere on 15th September 2017. This event may be visible from Earth as a ‘meteor’ flash, and entry dynamics simulations and results from observation of spacecraft entries at Earth are summarized to develop expectations for astronomical observability.

Comments: 10 pages, 2 figures, 2 tables

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:1708.05036 [astro-ph.EP]

(or arXiv:1708.05036v1 [astro-ph.EP] for this version)

Submission history

From: Ralph Lorenz [view email]

[v1] Wed, 16 Aug 2017 18:49:21 GMT (110kb)

https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/1708/1708.05036.pdf

Why is NASA terminating Cassini rather than putting it in perpetual orbit around Saturn? Is the info gain from a terminal descent really worth it and otherwise unobtainable?

Cassini’s thrusters are just about out of fuel. That means if we don’t use it for maximum science gain now, we’ll be unable it to maneuver it in the future, making a possibly contaminating encounter with one of the Saturn moons a real possibility. A tough decision, but in my mind, the right one.

Hasn’t Huygens probe already “contaminated” Titan ?

It’s also a matter of planetary protection. There is no perpetual orbit of Saturn that is permanently stable, just orbits that are currently stable. Any orbit will decay over time and NASA does not want to run the risk of any biological material that might still cling to Cassini winding up on Titan or Enceladus.

Don’t forget that Cassini also has three RTGs that we don’t want just landing anywhere. I mean, sure, they might be the spark that Titan and Enceladus need to get their native organisms really evolving, but still…

https://spacemath.gsfc.nasa.gov/Modules/8Mod7Prob2.pdf

For those who still think it is a shame to plunge Cassini into Saturn:

The probe is going to run out of maneuvering fuel. We cannot replenish it remotely. Even if we could, Cassini is over 20 years old. That means parts will wear out eventually. Better a controlled demise that will also produce unique science in the process than losing contact abruptly and then having who knows what happen with the probe.

It would just make more sense to build and launch a new probe with more advanced sensors and other technology. Perhaps a variation of the StarChip concept, “seeding” the Saturn system with little wafer-size probes for greater coverage. If a few of them are lost during the mission, it would not mean the end of the expedition, unlike if Cassini had a major failure.

I don’t easily get emotional, but the end of Cassini is a sad reminder that, after Juno is also over (2018-19) there will be no mission reaching the outer planets for at least 10-15 years, possibly longer :

This is thanks to the ridiculous overspending of resources at Mars. The irony is that, the more Mars is explored, the less habitable it looks. This is exactly the opposite for Enceladus and Europa (at least for now).

There’s also a long overdue follow up misison to Titan, Uranus and/or Neptune.

And I even hear of renewed efforts for a Mars sample return mission whose huge cost would kill the little non-Mars activities left at NASA.

I remember reading costs like $6B (almost like Europa+Titan/Enceladus +Icy giants mission). Sigh.

It’s not Mars. I is because of ISS, SLS and JWST

And remember that we had Space Shuttle launches from 1981 to 2011 which cost NASA $500 million per mission on average.

I see SLS launching better probes–and farther

https://smd-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/science-red/s3fs-public/atoms/files/HPS_Interstellar_Probe_1_July_2015-TAGGED.pdf

In the late 1970s the Soviet Union tried to one-up the Viking missions to Mars with a robotic sample return mission to the Red Planet. That project never came to fruition, but in the process it cost their space program plenty, not only in funding but also by negatively affecting their lunar and planetary missions already in progress.

http://www.russianspaceweb.com/msr.html

So yes, we have to weigh the value of bringing back a few pieces of Mars against the cost. We also better not assume there will either be living organisms or fossils in the surface materials we do bring back, so we don’t have a repeat of the attitude towards Viking when it did not give us unambiguous indications of life there.

I agree. I’d be more interested in rover missions to the Moon, which–despite its proximity to the Earth–is still hardly explored at all, especially its far side. The enigmatic TLP (Transient Lunar Phenomena, which sometimes make walled plains appear blank, fill large craters with pale, luminous haze, and create luminous red, orange, or pink patches that sometimes cover many square miles of the lunar landscape) would be fascinating to explore in situ using rovers, and:

There are numerous scientifically interesting locations (some of which–such as Tycho and the volcanic Marius Hills–were even on Apollo’s target list but were never visited), including the Straight Wall, Alphonsus, and Aristarchus, which are unexplored. There are also as-yet-unexplained dark patches, which have been observed for centuries, that appear in and around the craters Aristarchus and Eratosthenes, as well as the Herodotus Valley–which grow, change shape, and move around slowly during the course of each lunation. These too would be well worth investigating with rovers, as would–via relay orbiters–the far side (Tsiolkovsky–with its partly-melted mountains–and the Mare Orientale would be fascinating targets) and the dark polar craters. Plus:

A lander (or rover) mission to Mercury would literally “break new ground” (the MESSENGER orbiter was originally going to carry a small lander, but budget cuts resulted in it being omitted from the mission).

Orbiter/lander missions to NEOs (the same spacecraft could both orbit *and* land on small asteroids, due to their feeble gravity) would be inexpensive, have short transit times, and be scientifically rewarding.

It might be worthwhile to develop–as NASA was planning to do in the late 1970s–an ion drive SEPS (Solar Electric Propulsion Stage; the solar ion drive Mercury Transfer Module [MTM] of the ESA/JAXA BepiColombo Mercury spacecraft, which will propel the two orbiters to Mercury, is very similar to the Boeing SEPS). The SEPS could–in combination with inner-planet flybys (which would provide more science opportunities)–send probes to the outer planets at lower cost, because the probes and their launch vehicles could be smaller and lighter. As well:

Another interesting mission series could include a re-flight (which was proposed at the time, but not approved) of the lost CONTOUR mission to conduct flybys of Comets Encke, Schwassmann-Wachmann-3, and optionally also d’Arrest or Wirtanen (or other short-period comets that could be visited after Encke, depending on their positions at the time of launch), as well as one or more additional CONTOUR follow-on flights to visit other comets. Also:

Follow-ons to the drum-shaped Pioneer 6 – 9 solar monitoring probes (except for Pioneer 9, which died in 1983, these old spacecraft may *still* be functioning–no one has listened in on them since 2000) could be launched into similar solar orbits (between Earth and Venus, and between Earth and Mars). If their orbits were selected with care, short-period comets and Amor-, Apollo-, and Aten-class asteroids *would come to them* for flybys (in 1986, Halley’s Comet passed close enough to Pioneer 7 for its instruments to make scientifically useful observations), and:

These spacecraft would also–like Pioneer 6 – 9–collect data on the Sun, which would enable them, like the old probes, to provide up to 15 days’ advance warning of troublesome solar events (before the far side of the Sun rotated into line-of-sight view from the Earth). In addition:

These new Pioneer probes could also carry “push-broom” imagers (which are ideal for use on spin-stabilized spacecraft–the JunoCam aboard Juno is a “push-broom” camera [these new Pioneer probes could carry duplicates of the JunoCam]), which would enable them to image their comet and asteroid flyby targets.

The music of the spheres of Saturn:

http://www.system-sounds.com/saturn-sounds-part1/

I wonder if Arecibo or some other great dish could receive transmissions even after high-gain antenna is turned away. The relative cost of couple minutes of observational time must be very small compared to the whole Solstice extension!

I wonder about that, too–if Cassini could be pre-programmed to automatically switch to a low-gain antenna (as soon as its guidance system senses that the atmospheric buffeting has made its dish antenna point away from Earth, and its thrusters can no longer correct for that due to the increasing aerodynamic forces), we might be able to collect more in situ data on Saturn’s atmosphere. Using Arecibo or another big dish (or maybe using several dishes in unison, as was done during Voyager 2’s 1989 Neptune encounter–this enabled its data rate to be about the same as it was during the 1986 Uranus encounter, despite Neptune’s much greater distance), listening to Cassini’s last signals over a low-gain antenna could give us the most detailed information about Saturn’s atmosphere that we’re likely to get for many years.

Cassini’s grand finale

NASA’s Cassini mission to Saturn will end later this month with a plunge into the giant planet’s atmosphere. Jeff Foust examines the mission’s final days and what the spacecraft has accomplished since its beginnings three decades ago.

Tuesday, September 5, 2017

http://www.thespacereview.com/article/3320/1

To quote:

“Enceladus has no business existing, and yet there it is, practically screaming at us, ‘Look at me! I completely invalidate all of your assumptions about the solar system,’” Niebur said. “It’s just been a remarkable opportunity to study Enceladus and to unveil the secrets that it’s been keeping. It’s an amazing destination.”

…

She added she wished that Cassini—in good health other than its depleted fuel reserves—could operate even longer. “If we had more fuel, perhaps another ten years at Saturn would be just about right,” she said.

But, later in the teleconference, she acknowledged that perhaps now was the right time for Cassini to come to an end. “I feel a tremendous sense of pride in all that Cassini has accomplished,” she said. “In so many ways, we’ve really rewritten the textbooks on Saturn’s system.”

“Cassini has been a great mission. We’ve planned its end. We had its fuel last exactly the amount of time needed to get through Saturn’s summer solstice. So it’s time. It’s time to take our knowledge and our information and move that out into future missions, to the outer planets and beyond.”

Celebrating Europe’s science highlights with Cassini

http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Space_Science/Cassini-Huygens/Celebrating_Europe_s_science_highlights_with_Cassini

Paul Gilster said in this essay:

“Cassini doesn’t have HAL’s AI smarts, but I keep thinking about the final burn Arthur C. Clarke’s famous computer gave to the Discovery in the film 2010: The Year We Make Contact. ‘Poignant’ only begins to explore the complex emotions I’m feeling as we prepare to lose this bird.”

Humanity could probably use a good Jupiter turning into a sun kick in the pants right about now.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=38EDhpxzn2g

Cassini’s last look at Titan:

https://www.universetoday.com/137158/cassini-conduct-final-flyby-titan-crashing-saturn/

And Enceladus:

https://cosmosmagazine.com/space/cassini-s-last-look-at-enceladus

How the Cassini mission led a ‘paradigm shift’ in search for alien life

https://www.csmonitor.com/Science/2017/0912/How-the-Cassini-mission-led-a-paradigm-shift-in-search-for-alien-life