Thinking about Ursula Le Guin takes me to a single place. It is a snow-driven landscape, a glaciated world of constant winter called Gethen, whose name means ‘winter’ in the language of its people. I was reading The Left Hand of Darkness while snow pelted down outside one afternoon in upstate New York, waiting for my wife to get back from her teaching job, nursing a cup of tea and finding my mental location fusing with Le Guin’s fascinating world.

For The Left Hand of Darkness was a spectacular introduction to Le Guin. I had seen her name and even had, somewhere in the stacks, a copy of her first novel, Rocannon’s World (1966), part of an Ace Double that I never got around to reading. The Left Hand of Darkness came out in 1969 but it was in the late 70’s that I read it. I had been through “The Word for World is Forest” when reading Again, Dangerous Visions (1972), one of Harlan Ellison’s anthologies, and although it won a Hugo Award in 1973, I hadn’t found it as much compelling as didactic and all too linked to its era.

I just wasn’t, in other words, prepared for The Left Hand of Darkness, which explores a world in which the inhabitants have no fixed sex. I had read Samuel Delany’s Triton (1976), which deals in some of the same themes, without enthusiasm — I would learn later that Delany saw connections between the novel and Le Guin’s later novel The Dispossessed (1974) — although positing a world where people can change appearance and gender at will provided Delany with vast terrain for exploration.

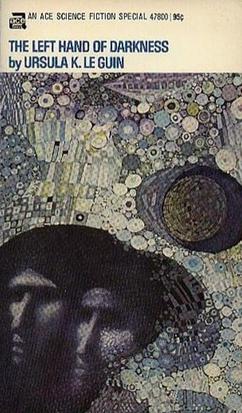

Image: Front cover of the first edition, with art by the Dillons. Cover depicts two faces against an abstract background. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

What made The Left Hand of Darkness stand out for me was simply the quality of its prose. Le Guin wrote the novel without sacrificing narrative flow, mining her subject with the gaze of a person who had been raised by two anthropologists (her mother’s book Ishi in Two Worlds (1960) had been widely acclaimed for its look at Californian Indian culture), but she was much more than a chronicler of scientific detail. A dispassionate eye couples in the novel with an explorer’s growing wonderment at place, at people. And the language…

Even as I think this the world’s sun dims between clouds ragathering, and soon a flaw of rain runs sparse and hard upriver, spattering the crowds on the Embankment, darkening the sky. As the king comes down the gangplank the light breaks through a last time, and his white figure and the great arch stand out a moment vivid and splendid against the storm-darkened south. The clouds close. A cold wind comes tearing up Port-and-Palace Street, the river goes gray, the trees on the Embankment shudder. The parade is over. Half an hour later it is snowing.

I can’t speak about The Dispossessed (1974) because I’ve never read it. In fact, there is a great deal of Le Guin I haven’t read. But when the writer died on Monday, I was reminded of my frequent intention of getting into her essays. A new volume called No Time to Spare: Thinking About What Matters had gone on my Amazon wishlist as soon as I saw it in 2017, but I also wanted to cycle back around to her Earthsea series.

As for The Left Hand of Darkness, though, what sticks with me as well as the evocation of place and the vivid sense of snow is the idea behind its civilization. The Hainish universe, beginning with Rocannon’s World, assumes that humans evolved not on Earth but on a planet some 140 light years away called Hain. Because its inhabitants colonized many stellar systems, the possibility was strong that any exploratory vessels from Earth would encounter populations that had been seeded as we had on their worlds. The effort becomes one of re-creating a lost interstellar civilization, using starships traveling close to the speed of light.

I’m told that the ansible was introduced in Rocannon’s World as a way of communicating instantaneously, so a civilization otherwise bound by lightspeed could manage its affairs. Many authors have used an ansible in their work since (and I also think of Dave Langford’s science fiction news and tip-zine of the same name). Le Guin’s galactic civilization becomes known as the Ekumen by the time of The Left Hand of Darkness, comprising fully 83 worlds.

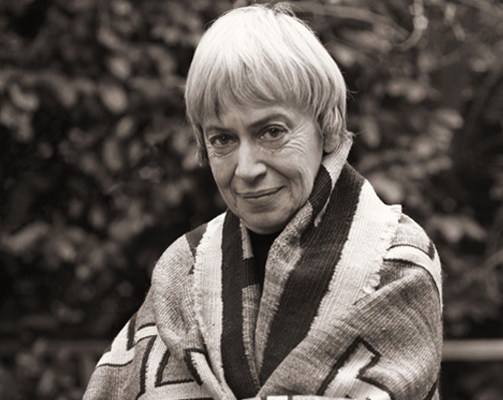

Image credit: Dana Gluckstein

I like the fact that Le Guin contrasted science fiction, which she insisted could be serious literature, with some of the creative-writing-workshop fiction that is all too easily churned out today:

“The thing to remember, however exotic or futuristic or alien the mirror seems, is that you are in fact looking at your world and yourself. Serious science fiction is just as much about the real world and human beings as realistic novels are. (Sometimes more so, I think when faced with yet another dreary story about a dysfunctional upper middle class East Coast urban family.) After all, the imagination can only take apart reality and recombine it. We aren’t God, our word isn’t the world. But our minds can learn a lot about the world by playing with it, and the imagination finds an infinite playing field in fiction.” Interview, Electric Lit, August 7, 2014

The Left Hand of Darkness took both Hugo and Nebula awards and became a fixture wherever science fiction was taught in the academy, surely the first SF novel to do so. No less a figure than Harold Bloom described the book in his monumental The Western Canon. I may not be the only writer who sees Le Guin invariably through its lens.

The New York Times has a fine obituary for Le Guin, as does the Washington Post, but if you want to get to know her views up close, read John Wray’s interview in the Paris Review. What a fine, spirited person! Here Wray, who is no slouch at working science fictional elements into his own novels, asks her about the genre:

I don’t think science fiction is a very good name for it, but it’s the name that we’ve got. It is different from other kinds of writing, I suppose, so it deserves a name of its own. But where I can get prickly and combative is if I’m just called a sci-fi writer. I’m not. I’m a novelist and poet. Don’t shove me into your damn pigeonhole, where I don’t fit, because I’m all over. My tentacles are coming out of the pigeonhole in all directions.

Hi Paul a quick note to say you mistakenly wrote “Left Hand of Winter” in the first paragraph! Feel free to delete this comment once you’ve corrected… And this was a lovely tribute. I feel much the same way.

Thanks! Just fixed the error.

Ursula K. Le Guin (21 October 1929 – 22 January 2018) was an American writer, known mostly for her work in science fiction and fantasy. … “But you look at Apollo, and he looks back at you. …. Think of the sunlight and the grass and the trees that bear fruit, Semley; think that not all roads that lead down lead up as well.”.

I have never liked the term “science fiction” for the two are diametrically opposed. It is intertaining to look at known history and imagine “what if?’ and explore possible outcomes within human culture. Imagine a world under a distant sun, impose reasonable constraints on evolution and history, and explore how that culture and civilization differs from our own. Then connect it to earth humans by space flight (and here a bit of irrationality has to creep in) so we earth humans can observe and interact.

I have read that Le Guin hated the ansible because it is simply too irrational, but without it, the story collapses. I have not read much of her writing, and I wish there was time to correct that mistake.

I always thought the ansible was a pretty cool way to allow for FTL travel.

But as Le Guin knew, that’s why it’s irrational. I fear science fiction may be doomed in the decades to come as the laws of relativity become more and more unyielding.

We may have to call it fantastical fiction, or as it was once referred to, speculative fiction. Space fantasies like Star Wars blur the lines between science and magic as it is.

Thank you SO much for your help on my Junior Fellows. I will forever be in your debt.

From,

Andrew Michaelson, University School

Andrew, it was my pleasure. I hope you’ll keep reading the Centauri Dreams site as well. Glad to have been able to help!

I reread The Left Hand of Darkness every 10 years or so.

Each time I find something new, something wonderful.

I’m sad that she has passed.

I’d like to urge you to try The Dispossessed. It’s a good book to be sure, but the main character is a brilliant theoretical physicist and I felt that she did a better job of showing a genius at work than just about anyone else ever has. It’s hard to do any time, and even more so when the character’s supposed expertise is so far from the writer’s.

So many good stories. Also, a lot of what I think is crap. But above, one of your commenters quoted from “Semley’s Necklace,” a classic. Other stories: “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omeles,” “Before The Revolution.” But her classic, for which one could die happy having written it, is “The Dispossessed.” It is simply incredible. A compare and contrast between two social systems; a story of how science works; a story of the growth of a man. It operates on sooooo many levels. You owe it to yourself to read it. IMHO of course.

Listen to Ursula K. Le Guin’s Little-Known Space Opera

“Rigel 9,” a collaboration with the composer David Bedford, tells the story of an astronaut who isn’t quite sure where home is.

by Cara Giaimo

January 24, 2018

If you’re an Ursula K. Le Guin fan, you’ve likely spent a lot of time in Earthsea, home to endless archipelagos and magical beings. You might have ventured to Gethen, with its glaciers and androgynes.

But you may not yet have made it to Rigel 9, a world that offers small red aliens, two-toned shadows from its double sun, and—depending on who you believe—a beautiful golden city. The planet is the setting of the little-known space opera, also called Rigel 9, released in 1985. The opera features music by avant-garde classical composer David Bedford, and a libretto written by Le Guin.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/ursula-le-guin-forgotten-space-opera-david-bedford

There is also “The Lathe of Heaven” which has been adapted for tv twice. The first version, and the one Le Guin thought was best, can be viewed on YouTube:

The Lathe of Heaven

I know this took place in the distant year of 1980, but who remembers the PBS film version of LeGuin’s classic work The Lathe of Heaven, about a fellow named George Orr whose dreams literally become reality and how his psychiatrist tries to use his patient’s powers for his ideas of good, with Twilight Zone twist ending results.

The film version is based on her 1971 novel of the same title. It was definitely one of the better science fiction films of its day and now, but did not get the widespread distribution it deserved.

Lathe is currently being made into a play:

http://www.thehoya.com/lathe-heaven-director-talks-alternate-realities-representation-theater/

https://dctheatrescene.com/2018/01/26/natsu-onoda-power-adaptation-ursula-le-guins-lathe-heaven/

Here is an article on the 1980 film version, which has embedded the entire film from YouTube. Apparently a remake was done in 2000, but I have not seen that one.

http://www.oregonlive.com/tv/2018/01/how_ursula_k_le_guins_the_lath.html

Dec 5, 2017·5 min read

Ursula K. Le Guin Explains How to Build a New Kind of Utopia

We keep writing dystopias instead of envisioning a better world—maybe what we need is balance.

By Ursula K. Le Guin

https://electricliterature.com/ursula-k-le-guin-explains-how-to-build-a-new-kind-of-utopia-15c7b07e95fc

Thank you for observing Ursula Le Guin’s passing. The world is better off for her. If you were impressed and engaged by the prose of ‘The Left hand of Darkness’, read the ‘The Dispossessed”. Every characterization of a character’s mind is steeped and rendered in the characterization of their group mind and history’s mind.

Point taken. You’re the third, Harold, after Tim Kyger and Mark Olson, to urge me to read The Dispossessed, and that’s enough for me. Thanks to all three of you.

Le Guin’s The Dispossessed and Vance’s Emphyrio are mirrors of a dystopian path into which western society still could sail. Vance loved sailing, whereas Le Guin loved humanism. Both were more interested in the psyche than in machines.

Thanks for writing about this wonderful person.

Ursula Le Guin without the K is like Arthur Clarke without the C. It just loses something.

Ursula K. Le Guin on “Spare Time,” What It Means to Be a Working Artist, and the Vital Difference Between Being Busy with Doing and Being Occupied with Living.

In praise of the mundane, unquantifiable, impractical activities that feed creative work and fill life with meaning.

By Maria Popova

Most people are products of their time. Only the rare few are its creators. Ursula K. Le Guin (October 21, 1929–January 22, 2018) was one.

A fierce thinker and largehearted, beautiful writer who considered writing an act of falling in love, Le Guin left behind a vast, varied body of work and wisdom, stretching from her illuminations of the artist’s task and storytelling as an instrument of freedom to her advocacy for public libraries to her feminist translation of the Tao Te Ching and her classic unsexing of gender.

In her final years, Le Guin examined what makes life worth living in a splendid piece full of her wakeful, winkful wisdom, titled “In Your Spare Time” and included as the opening essay in No Time to Spare: Thinking About What Matters (public library) — the final nonfiction collection published in her lifetime, which also gave us Le Guin on the uses and misuses of anger.

Full article here:

https://www.brainpickings.org/2018/01/24/ursula-k-le-guin-spare-time/

Mother to Us All: On Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Language of the Night

LeGuin has “a style as clear as sunlight and a moral sense as strong as reinforced concrete,” wrote the Philadelphia Inquirer back in 1979.

January 25, 2018

By Book Marks

http://lithub.com/mother-to-us-all/

And on the growing trend of science fiction moving away from dystopias and other dark, nihilistic themes:

http://www.ozy.com/fast-forward/sci-fi-doesnt-have-to-be-depressing-welcome-to-solarpunk/82586?mc_cid=fbca4ba6c5&mc_eid=a9c2fda3f4

Welcome to solarpunk, a new genre within science fiction that is a reaction against the perceived pessimism of present-day sci-fi and hopes to bring optimistic stories about the future with the aim of encouraging people to change the present. The first book that explicitly identified as solarpunk was Solarpunk: Histórias ecológicas e fantásticas em um mundo sustentável (Solarpunk: Ecological and Fantastic Stories in a Sustainable World), a Brazilian book published in 2012. In 2014, author Adam Flynn wrote Solarpunk: Notes Toward a Manifesto.

Ursula K. Le Guin’s Best Life Advice

January 24, 2018

By Emily Temple

http://lithub.com/ursula-k-le-guins-best-life-advice/

My Last Conversation with Ursula K. Le Guin

John Freeman on a Cherished Visit to the Beloved Writer’s Home

January 24, 2018

By John Freeman

http://lithub.com/my-last-conversation-with-ursula-k-le-guin/

R.I.P. to a very talented lady.

I’ve done some reading of Earthsea, but I always meant to delve deeper into her works. I’ll be sure to read ‘The Left Hand of Darkness’.

Even what doesn’t happen is epic

Nick Richardson

Vol. 40 No. 3 · 8 February 2018

pages 34-36 | 3144 words

Science fiction isn’t new to China, as Cixin Liu explains in Invisible Planets, an introduction to Chinese sci-fi by some of its most prominent authors, but good science fiction is. The first Chinese sci-fi tales appeared at the turn of the 20th century, written by intellectuals fascinated by Western technology.

‘At its birth,’ Cixin writes, science fiction ‘became a tool of propaganda for the Chinese who dreamed of a strong China free of colonial depredations’.

One of the earliest stories was written by the scholar Liang Qichao, a leader of the failed Hundred Days’ Reform of 1898, and imagined a Shanghai World’s Fair, a dream that didn’t become a reality until 2010. Perhaps surprisingly, given the degree of idealistic fervour that followed Mao’s accession, very little utopian science fiction was produced under communism (in the Soviet Union there was plenty, at least initially). What little there was in China was written largely for children and intended to educate; it stuck to the near future and didn’t venture beyond Mars.

By the 1980s Chinese authors had begun to write under the influence of Western science fiction, but their works were suppressed because they drew attention to the disparity in technological development between China and the West. It wasn’t until the mid-1990s, when Deng’s reforms began to bite, that Chinese science fiction experienced what Cixin calls a ‘renaissance’.

Full article is online here:

https://www.lrb.co.uk/v40/n03/nick-richardson/even-what-doesnt-happen-is-epic

To quote:

Cixin’s view of the universe as a dark forest may be pessimistic, but his view of humanity and its future is extremely optimistic. We are not in the end times: we are babies at the foot of a long staircase. We will develop superhard nanomaterials that will allow us to build an elevator to space. We will develop rockets powered by nuclear fusion that will take us way beyond the Oort cloud. One day we will be capable of building ring-shaped artificial planets that produce their own gravitational fields. We will live in houses shaped like leaves that dangle from the branches of enormous artificial trees; we won’t carry mobile phones or smart devices since any surface can be turned into an information screen at will.

Cixin constantly reminds us of our technological infancy by imagining civilisations that are way ahead of us, lighting the path. One of the most powerful sequences comes towards the end of The Dark Forest, when Earth’s fleet meets a Trisolaran vehicle that makes our most advanced spaceships look clunky:

The probe was a perfect teardrop shape, round at the head and pointy at the tail, with a surface so smooth it was a total reflector. The Milky Way was reflected on its surface as a smooth pattern of light … Its droplet shape was so natural that observers imagined it in a liquid state, one for which an internal structure was impossible.

What Ursula K. Le Guin Meant to Me: Four Writers Remember

How a Legendary Writer Made Lives Better

February 5, 2018

By Literary Hub

http://lithub.com/what-ursula-k-le-guin-meant-to-me-four-writers-remember/

BOOKS AND ARTS

23 February 2018

Ursula K. Le Guin: an anthropologist of other worlds

Marleen S. Barr remembers a titan of science fiction.

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-02439-7

Ursula K. Le Guin: Dictators are Always Afraid of Poets

On Nature Writing, Technology, and Poetic Form

April 6, 2018 By David Naimon

Prior to my first interview with Ursula, my wife and I were planning a hiking trip to the North Cascades National Park along the border between Washington State and Canada. But wildfires, the new summer norm in the Pacific Northwest, had another idea, shutting down the park and sending us scrambling for last-minute alternatives.

I knew of Ursula’s long-standing love of Steens Mountain in the remote high desert of the farthest corner of southeastern Oregon, a landscape that had informed the world of her novel The Tombs of Atuan, as well as her poetry-photography collaborative collection Out Here. Even though we had yet to meet, I decided to call her up and see if, by chance, she had any suggestions to save our vacation.

“Do you know about dark skies?” Ursula asked, clearly excited to share. “That this is one of the only places left in the United States where you can experience true darkness, see the stars as if under a sky with virtually no light pollution?” she continued, her voice full of the wonder of countless nights under that very sky.

Soon my wife and I found ourselves “out there,” in a town of fewer than 20 people, in a hotel run by fifth-generation Oregonians, in a region where wild horses still roamed under the brightest of dark skies.

“Tell them Ursula and Charles sent you,” she told us, and we were taken in and cared for by the rare breed of people who lived out there, farmers and ranchers who could trace an unbroken lineage back to the first white settlers in the region.

As my wife and I sat together beneath the “blazing silence,” “the endless abyss of light,” contemplating our place in the world, in the universe, we were, unbeknownst to us, learning about Ursula through these dark skies and the people they illuminated, long before Ursula and I were to meet face-to-face.

Now, when I think of Ursula’s poetry it’s this, these unadulterated skies and the people who generation after generation have lived beneath them, I think of most. If imagination is the word that comes first to mind about her fiction, contemplation is the word I’d most associate with her poetry.

She does not write science fiction poems, poems taking place in imagined other worlds, but rather contemplates our place in this one. If one removes human light from the sky, allowing it to become again “eternity made visible,” if one spends time in a land where antelope, coyote, pelicans, and raptors far outnumber human souls, certain questions of meaning inevitably arise.

What does true fellowship with the nonhuman other—animals, birds, plants, the land itself—look like? What human tools and technologies, stories and language, are worth passing on generation to generation? What is our proper relationship to mystery, to wonder, to what we don’t know, to what we can’t?

Full article here:

https://lithub.com/ursula-k-le-guin-dictators-are-always-afraid-of-poets/

Subjectifying the Universe: Ursula K. Le Guin on Science and Poetry as Complementary Modes of Comprehending and Tending to the Natural World

“Science describes accurately from outside, poetry describes accurately from inside. Science explicates, poetry implicates. Both celebrate what they describe.”

By Maria Popova

Subjectifying the Universe: Ursula K. Le Guin on Science and Poetry as Complementary Modes of Comprehending and Tending to the Natural World

“What men are poets,” the Nobel-winning physicist Richard Feynman asked in what may be the world’s most poetic footnote, “who can speak of Jupiter if he were a man, but if he is an immense spinning sphere of methane and ammonia must be silent?”

Two centuries before him, the poet William Wordsworth had insisted that “poetry is the breath and finer spirit of all knowledge… the impassioned expression which is in the countenance of all Science.”

I too have long cherished this unheralded common ground between poetry and science as complementary worldviews of contemplation and observation — a cherishment of which The Universe in Verse was born — and have encountered no more beautiful an articulation of it than the one Ursula K. Le Guin (October 21, 1929–January 22, 2018) offered in the preface to her final poetry collection, Late in the Day (public library).

Full article here:

https://www.brainpickings.org/2018/04/10/ursula-k-le-guin-late-in-the-day-science-poetry/

URSULA K. LE GUIN, EDITING TO THE END

DAVID NAIMON ON COLLABORATING WITH A LITERARY LEGEND

May 22, 2018 By David Naimon

Ursula’s final words to me, her final edits on the manuscript of our collected conversations, were in pencil. We had talked in one of these conversations about technology, about how, in her mind, she was unfairly labeled a Luddite. That some of the most perfect tools—a pestle, a kitchen knife—were in fact perfected technologies. I had just received the manuscript from her days before, and the pencil on it reminded me of the aura of in-the-world magic this whole endeavor, bringing a book into the world together, had assumed.

Full article here:

https://lithub.com/ursula-k-le-guin-editing-to-the-end/

To quote:

Perhaps the biggest moment for Luke Skywalker is not that glorious heroic shot that destroyed the Death Star, but his everyday attention to cleaning his little droid, the very cleaning of which led him to discover, as if by chance, the world-saving message from Leia. But I suspect Ursula would want us to dispense of Luke Skywalker, of masculine hero narratives altogether. She’d more likely point to Lao Tzu, who wrote the Tao Te Ching: The Book of the Way and its Power during the Warring States Period, a particularly terrible time in China, and who advocated wu wei, “doing by not-doing” as a response to it.

Of course, Lao Tzu strikes the Western conflict-oriented mind as incredibly passive. “Don’t do something, just sit there.” That’s where he is so tricky and so useful. There are many different ways of just sitting there.

Telling Is Listening: Ursula K. Le Guin on the Magic of Real Human Conversation

“Words are events, they do things, change things. They transform both speaker and hearer; they feed energy back and forth and amplify it. They feed understanding or emotion back and forth and amplify it.”

https://www.brainpickings.org/2015/10/21/telling-is-listening-ursula-k-le-guin-communication/

Every act of communication is an act of tremendous courage in which we give ourselves over to two parallel possibilities: the possibility of planting into another mind a seed sprouted in ours and watching it blossom into a breathtaking flower of mutual understanding; and the possibility of being wholly misunderstood, reduced to a withering weed. Candor and clarity go a long way in fertilizing the soil, but in the end there is always a degree of unpredictability in the climate of communication — even the warmest intention can be met with frost.

Yet something impels us to hold these possibilities in both hands and go on surrendering to the beauty and terror of conversation, that ancient and abiding human gift. And the most magical thing, the most sacred thing, is that whichever the outcome, we end up having transformed one another in this vulnerable-making process of speaking and listening.

Why and how we do that is what Ursula K. Le Guin (October 21, 1929–January 22, 2018) explores in a magnificent piece titled “Telling Is Listening” found in The Wave in the Mind: Talks and Essays on the Writer, the Reader, and the Imagination (public library), which also gave us her spectacular meditations on being a man and what beauty really means.