Fifty years ago today, 2001: A Space Odyssey was all the buzz, and I was preparing to see it within days on a spectacular screen at the Loew’s State Theater in St. Louis. The memory of that first viewing will always be bright, but now we have seasoned perspective from Centauri Dreams regular Al Jackson, working with Bob Mahoney and Jon Rogers, to put the film in perspective. The author of numerous scientific papers, Al’s service to the space program included his time on the Lunar Module Simulator for Apollo, described below, and his many years at Johnson Space Center, mostly for Lockheed working the Shuttle and ISS programs. But let me get to Al’s foreword — I’ll introduce Bob Mahoney and Jon Rogers within the text in the caption to their photos. Interest in 2001 is as robust as ever — be aware that a new 513-page book about the film is about to be published. It’s Michael Benson’s Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece. Let’s now return to the magic of Kubrick’s great film.

By Al Jackson, Bob Mahoney and Jon Rogers

Foreword

By the 1st of April, 1968 I had been working in the Apollo program as an astronaut trainer for the Lunar Mission Simulator, LMS, for 2 and a half years. I had also been a science fiction fan for 15 years at that time, so I had kept up with, as best as one could, Stanley Kubrick’s production of 2001: A Space Odyssey. The film premiered in Washington, DC on April 2, 1968 (it had an earlier test showing in New York). I think it premiered in Houston on a Friday, April 5 (a day after the Martin Luther King assassination). Boy! I sure tried to wangle a ticket for that but could not. However I did see the film on April 6, at the Windsor Theater in Houston on a gorgeous 70mm Cinerama screen. It was a stunning film since I had been nuts about space flight since I was 10 years old. A transcendental moment! A few things:

(1) Having read everything Arthur C. Clarke had written, I grasped essence of the story the first time through. I saw the film six more times at the Windsor in 1968, and once in March of 1969 on another big screen in Houston. That was the last time I have seen it in true 70mm. All was confirmed when I read Clarke’s novel a few weeks later.

(2) On Monday morning, the 8th of April, 1968 Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin were scheduled in the LMS for training. I remember James Lovell, Bill Anders and Fred Haise standing around the coffee pot talking to Buzz. He surprised me by holding forth on how 2001’s narrative seemed to him a rework of ideas by Clarke in Childhood’s End, as well as Clarke’s thoughts in essays. In all the time he spent in the simulator, I don’t think we ever talked science fiction.

(3) Having been ’embedded’ in space flight first as a ‘space cadet’ and then plunged, as a NASA civil servant, into the whirlwind that was Apollo, I had a jaundiced eye for manned space flight. I was thrilled to see a nuclear powered exploration spacecraft, a monstrous space station and a huge base on the Moon, all technically realizable in 30 or so years. But I was getting pretty seasoned on the realities of manned spaceflight, so a little voice in the back of my brain said No Way, No How is that going to be there in 30 years. It all passed into an alternate universe in 2001. Yet I didn’t imagine that no manned flight would go out of low Earth orbit in 50 years!

Half a Century of 2001

April of 2018 marks the fiftieth anniversary of the release of Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke’s science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey and the novel of the same name. The narrative structure of the film is a transcendent philosophical meditation on extraterrestrial civilizations and biological evolution, a theme known in science fiction prose from H.G. Wells to the present as BIG THINKS. Books, articles, and even doctoral dissertations have been written about the film. Framing these deeper speculations was a ‘future history’ constructed on a foundation of rigorously researched, then-current scientific and engineering knowledge. We address this technology backdrop and assess its accuracy. We’ll leave any commentary on the film’s philosophy to film critics and buffs.

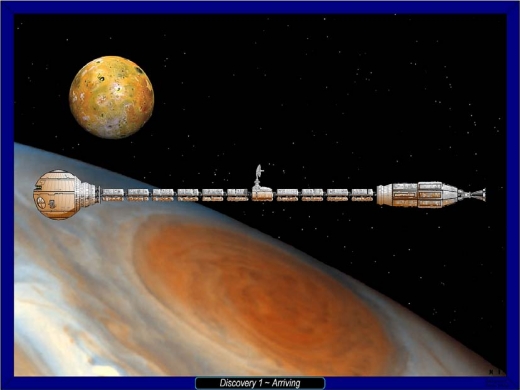

Hailed at the time as a bold vision of our future in space, it presented both Kubrick’s and. Clarke’s predictions of spaceflight three decades beyond the then-current events of the Gemini and early Apollo programs. One’s impression now is that Kubrick and Clarke were overly optimistic. We certainly don’t have 1000-foot diameter space stations (the one shown in the film was SS Five; we never see the other four) spinning in Earth orbit and multiple large bases on the lunar surface supporting hundreds of people. And the Galileo and Cassini probes were a far cry from nuclear-powered manned missions to the outer planets.

But those extrapolations are programmatic in nature, not technology-related. One must recall that the film was conceived in early 1965, when the space programs of both the U.S. and U.S.S.R. were racing ahead at full speed. Prose science fiction of the late 1930’s through 1965 is an indicator that many writers assumed extensive spaceflight exploits were perfectly feasible (even inevitable) by the turn of the last century. (It should be noted that many prose science fiction writers such as Robert Heinlein, Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, and many others, hedged their bets and put the technological developments depicted in the film more than 100 years beyond 2001.) The many social ,economic and political circumstances that would place pressures on space program funding were not fully understood at the film’s production. This was also at a time when individual countries unilaterally pursued their own space programs.

Yet when one looks beyond the obvious programmatic “overshoot” of the film to the technical and operational details of their portrayal of spaceflight, Kubrick and Clarke’s cinematic glance into the crystal ball seems much more remarkable. There are few sources of technical material about the spacecraft in the film although we know that Marshall engineers Frederick Ordway and Harry Lange (7,8), spent nearly three years designing the technical details for the film with the help of both the American and British aerospace industries. Their considerable efforts are evident even down to the details.

Image: Discovery in Jupiter space. Credit: Jon Rogers.

Space Transport to Earth Orbit

Take the Orion III space plane. Excluding the Pan Am logo (no one would have expected Pan Am to go bankrupt only 15 years later!), the space plane ferrying Dr. Floyd into Earth orbit shares an amazing number of features with the once active space plane, the Space Shuttle. Not only does it have a double-delta wing, but the three sweep angles (both leading and trailing edges) are within 10 degrees of those on NASA’s shuttle. One also finds it intriguing (as superficial a matter as this might be) that the back ends of both vehicles have double bulges to accommodate their propulsion systems.

Watching the docking sequence cockpit view in the film is like sitting in the flight engineer’s seat on a shuttle’s flight deck. Three primary computer screens, data meters spanning the panel over the windshield, a computer system by IBM, dynamic graphics of the docking profile can be found in the Orbiters. The real Shuttle approaches not nose-first but top-first, and the dynamic images of space station approaches are displayed on laptop computers, not the primary computer screens. The laptop imagery in the Shuttles was due to the evolution in computer technology, which did not exist when the 2001 space planes were conceived.

Another implied technical feature of the Orion III docking operation is that the space plane’s crew is not doing the flying; the space plane’s computers are. While this isn’t quite the way the Shuttle docked to the space station today (the crews flew most of the approach and docking manually but their stick and engine-firing commands pass through the computers), fully automatic dockings have been the norm for Russian Soyuz and Progress for many years and for the ESA Automated Transfer Vehicle. The premise of the space plane flying itself as the crew monitors its progress was standard operating procedure for Shuttle ascents and entry.

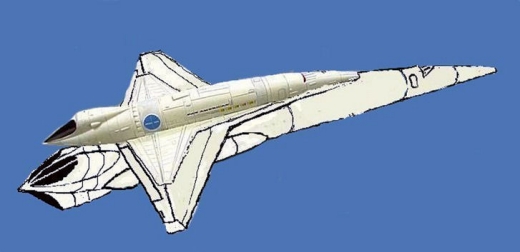

Speaking of ascent, the film leaves us to speculate on how the Orion III achieved orbit. The book 2001: A Space Odyssey [1] fills this in—and here we find a serious divergence from the stage-and-a-half vertically launched shuttle. It is now known that the Orion III was a ‘III’ because the first stage, Orion I, was the booster (while Orion II was a cargo carrier [2a] (see note 1)]. In the novel, Clarke clearly describes the Orion space liner configuration as a piggy-back Two-Stage-to-Orbit (TSTO), Horizontal Take Off and Horizontal Landing (HTOHL) tandem vehicle launched on some form of railed accelerator sled [2a].

Image: Orion 1 and 3 mated for flight. Credit: Ian Walsh, who in addition to being a key player in designing and building the largest aperture telescope in the southwest of England is also a builder of scale models both factual and fictional.

This mid-60’s speculation for an ascent/entry transportation system is remarkably in line with (minus the rail sled) many of the European Space Agency’s extensive ’80s/’90s design studies of their Sänger II/Horus-3b shuttle [9]. (A multitude of TSTO studies in the Future European Space Transportation Investigations Programme [9] echoed the space transportation system suggested in the film 2001.) Perhaps Clarke’s prescience (and ESA’s design inspiration) stemmed not from looking forward but from looking back. Amazingly, basic physics had guided Eugen Sänger and Irene Brent—in 1938!—to define this fundamental configuration (including the rail sled) for their proposed ‘orbital space plane’ the Silbervogel.

Image: The 2001 space plane going for orbit. Credit: Jon Rogers.

It is interesting that Arthur C. Clarke wrote a novel in 1947, Prelude to Space, with a horizontal take off two-stage-to-orbit spacecraft and twenty one years later it was depicted, though one has to read the novel to find this out. The second stage in Prelude to Space is nuclear powered while the Orion III is liquid oxygen-liquid hydrogen propulsion.

In recent times it was noticed that there was another shuttle to space station V, the Russian ‘Titov’, but it can only be seen inside an office on the station.

Image: Model of the Russian Titov shuttle, a tough catch unless you’re watching the movie extremely closely. Credit: Ian Walsh.

Zero G

One of the best aspects of 2001, and certainly a significant reason most knowledgeable space enthusiasts admire it, is its artistic use of true physics. Nearly every spaceflight scene shown in 2001 conforms to the way the real universe works. (And talk about a compliment to the special effects crew of the 1968 film — the Apollo 13 team achieved most of their zero-g effects by filming inside the NASA KC-135 training aircraft as it flew parabolic arcs.) 2001 has had a lasting influence on using facts in the story telling: in recent years, Gravity, Interstellar and The Martian used reality as a canvas.

If you are in an orbiting spacecraft that’s not undergoing continuous acceleration due to its own propulsion, you can’t just walk around like you’re heading into the kitchen from the living room. Those bastions of “science” fiction pop culture, Star Trek and Star Wars, conveniently used an old prose science fiction ploy, ‘super-science’ ‘field-effect’ gravity, to permit walking (due to F/X budgets or artistic license ). However, careful comparison of the 1968 film scenes to those of crew members operating in spacecraft today quickly reveals that Kubrick dealt with the technical (and potentially F/X-budget-busting) challenge of faking zero gravity by blending scientifically legitimate speculation, real physics on the soundstage, and a touch of artistic license that collectively helped to produce visually compelling aesthetics.

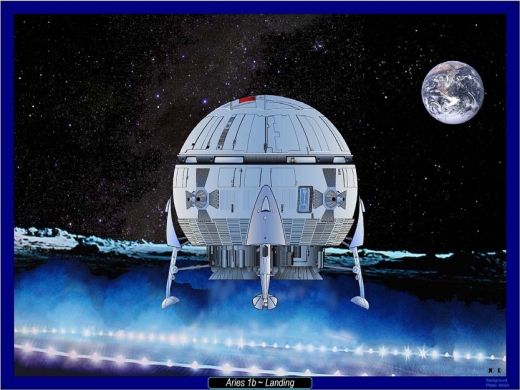

In 2001, when the crew move about in non-rotating parts of their spacecraft, they walk (and even climb up and down ladders) on Velcro (or some similar material) with special footwear. We first see this in the Orion III ‘shuttle’, when a stewardess walks in zero g using grip-shoes. In fact, one of the more visually interesting sequences (the stewardess heading up to the cockpit in the Aries IB moon shuttle) gains its impact with the idea — the stewardess calmly walks her way up a curving wall until she’s upside down. Station astronauts must fidget anxiously when they watch this scene since they would accomplish a similar trip today in seconds with just a few pushes. In today’s spacecraft, you don’t walk anywhere; you float.

DCF 1.0

Image: Jon Rogers on the right, with Jack Hagerty, who along with Ian Walsh added comments and suggestions for this essay. Some background on Jon Rogers: An A.I.A.A. member for many years, Jon started his career as QA inspector on Apollo Hi-Gain antenna system, built microcircuits for the Space Shuttles, and was Sr. Mfg. Engineer on the GOES, INTELSAT-V, SCS1-4 Satellites. Mr. Rogers has written articles, co-authored/illustrated the Spaceship Handbook, and presented to the A.A.S. national convention, on the early history of spaceships. He received his degree from SJSU in 2000. Credit: Al Jackson.

Kubrick adopted the concept (not necessarily an unreasonable one for the mid-60s) that routine space flyers would insist on retaining the norms of earth operations, including walking, while in zero gravity. (In fact, most crewmembers do prefer at least a visual sense of a consistent up-and-down in spacecraft cabins.) While this helped him out of a major cinematic challenge, it predated the early 70’s Skylab program, when astronauts finally had enough room to really move around and learn the true freedom of zero gravity. You’ll note too that the flight attendant’s cushioned headgear also helped avoid the likely impossible task of cinematically creating freely floating long hair, a common sight in today’s downlink video.

2001 was probably the first space flight film to actually use zero g to depict zero g. In the scene where astronaut Dave Bowman re-enters the Discovery through the emergency hatch, the movie set was built vertically. This allowed actor Keir Dullea to be dropped, and thus undergo a second or two of freefall, before the wire harness arrested his plunge. (Note 5)

Of course, today’s space flyers use velcro to secure just about everything else. Cameras, checklists, pens, food containers — you can tell the space items apart from their earthbound cousins by their extensive strips of fuzzy tape. Unfortunately, this convenient fastener’s days in the space program may be numbered for long-duration flight. Velcro, composed of tiny plastic hooks, eventually wears out and small pieces break off and can become airborne hazards to equipment and crew. Consequently, long-stay crews keep equipment and themselves in place with other fastening techniques: Magnets, bungee cords, plastic clips, or even just simple foot straps.

Image: Bob Mahoney. Passion for spaceflight propelled Bob Mahoney through bachelor’s and master’s degree programs in aerospace engineering at the University of Notre Dame and the University of Texas at Austin, respectively. Love of writing carried him into lead editorships of his high school’s literary magazine and Notre Dame Engineering’s Technical Review. Bob discovered an outlet for both of these passions while serving nearly ten years as a spaceflight instructor in the Mission Operations Directorate at Johnson Space Center. While working at JSC, he taught astronauts, flight controllers, and fellow instructors in the disciplines of orbital mechanics, computers, navigation, rendezvous, and proximity operations. His duties included development of simulation scripts for both crew-specific and mission control team training. Bob supported many missions, including STS 35, the first flight of Spacelab post-Challenger, and STS 71, the first shuttle docking to Mir. As Lead Rendezvous Instructor for STS 63, the first shuttle-Mir. rendezvous, and STS 80, the first dual free-flyer deploy-and-retrieve, he ensured both crew and flight control team preparedness in rendezvous and proximity operations.

Artificial Gravity

Kubrick and Clarke’s other method of fighting zero g was well-established in the literature of the time: centrifugal force. The physiological effects of zero g on humans had been a worry from the early days of theoretical thinking about spaceflight. Some thought it might be beneficial, but many worried that since the human body evolved in one g, long exposure to no or reduced gravity might be detrimental. In the film, both the large space station orbiting Earth and the habitation deck of the Jupiter mission’s Discovery spacecraft rotate to create artificial gravity for the inhabitants. While Gemini 11 achieved this during an experiment, the general trend in space operations has been to live with zero gravity (properly termed microgravity) while combating its effects on the human body through exercise. This path was chosen for two reasons: A rotating spacecraft’s structure must be significantly sturdier (and thus more massive, and thus more expensive to launch) to handle the stresses of spinning, and the utility of zero g seems to outweigh its negative aspects. Yet one must note that research on the ISS has indicated there are limits to how much exercise and other similar countermeasures can counteract physical deterioration. Living in zero g for extended periods of time, for interplanetary flight, now no longer seems possible. This is one aspect of space medicine research that makes the ISS such an important laboratory.

Ordway and Lange designed the Discovery‘s crew quarters centrifuge realistically to simulate/generate 0.3 g while counteracting Coriolis forces, but a 300-foot diameter wheel was just not feasible as a set. Nevertheless, Vicker’s aircraft built the fully working prop with remarkable accuracy. (6) The space station interior set did not rotate, but consisted of a fixed curved structure nearly 300 feet long and nearly 40 feet high. (2) The curve was gentle enough to permit the actors to walk smoothly down the sloping floor and maintain the desired illusion.

Food

A bit of a miss here, more dictated by the design of ‘space food’ in the 1960s than anything else. Whereas the Council of Astronautics’ Chief Heywood Floyd sips liquid peas and carrots through straws on the way to the Moon and the Jupiter-bound Discovery crew eats what could best be described as colored paste, today’s astronauts get to eat shrimp cocktail and Thanksgiving turkey dinners. Of course, these are either dehydrated or military-style MREs (Meals Ready to Eat), but they beat the zero-g mess problem simply by being sticky via sauce or gravy. The most accurate culinary prediction of Kubrick and Clarke was the lunar shuttle bus meal: sandwiches. However, when an ISS crewmember prepares that old staple peanut butter and jelly, he or she uses tortillas in place of bread. Like worn-out Velcro, bread makes too many crumbs, and crumbs can get into the electronics.

The galley on Discovery, however, has its counterpart on the Shuttle. While it didn’t automatically dole out an entire five-course meal based on crewmember selection (astronauts did this manually before liftoff back in Houston, and then their meals get packed in storage lockers), the shuttle galley did let them heat up items that are supposed to be hot and rehydrate that shrimp cocktail. The zero-gravity toilet instructions shown in the film, an intentional Kubrick joke, are much longer than the shuttle’s Waste Containment System crew checklist.

Propulsion

While the Orion III space plane’s external propulsion elements hint at systems a few years beyond even today’s state-of-the-art (possible air intakes for a scramjet and a sloping aerospike-like exhaust nozzle), the spherical Aries 1B moon shuttle has rocket nozzles which would look perfectly at home on the old lunar module. Kubrick was smart not to show exhaust as they fired, only lunar dust being blown off the lunar surface landing pad. Ordway has indicated that the propellants were LOX/LH2 and thus the exhaust would be extremely difficult to see in a vacuum in sunlight. Even the MMH/N2O4 shuttle jet firings washed out during orbital day.

One particular propulsion depiction potentially unique to 2001, which Kubrick likely used more for cinematic aesthetics as well for the sake of realism, is the roar, whine, or boom of engines in the space vacuum. Even Apollo 13 fell down here, going for the rock ‘n’ roll excitement of the service module’s jets pounding away with bangs and rumbles in external views. (Arguably Kubrick’s most inspired move ever was to overlay Johann Strauss’s ‘The Blue Danube’.) Something that almost all fictional space TV and movies miss is the cabin noise of those jets firing, however. Unlike the vacuum outside, a spacecraft’s structure can carry sound and the Shuttle crews do hear their jet firings; at least the ones up front near the cabin. They are quite loud — crewmembers have compared them to howitzers going off. (The 2013 film Gravity did use ‘interior’ sounds well, subtle enough that one does not catch it at first. Sounds transmitted through space suits and ship structures, and a clever use of the vacuum!)

2001‘s one big cinematic overshoot propulsion-wise is the nuclear rockets of the interplanetary Discovery. While deep-space probes such as Voyager, Galileo, and Cassini employ RTG units to generate electricity with the radioactive heat of their plutonium, no nuclear propulsion has ever flown in space to date, primarily because there has been no return to research on nuclear propulsion. (Note: The U.S. NERVA nuclear thermal rocket program was not canceled until 1972, a full four years after the movie’s release.)

The Discovery was powered by a gaseous fission reactor for rocket propulsion. The highest reactor core temperature in a nuclear rocket can be achieved by using gaseous fissionable material. In the gas-core rocket concept, radiant energy is transferred from a high-temperature fissioning plasma to a hydrogen propellant. In this concept, the propellant temperature can be significantly higher than the engine structural temperature.

Regarding the depiction of that nuclear propulsion in the film, Discovery was actually missing a major component: massive thermal radiators. As any nuclear engineer could point out (and described properly in the novel), these huge panels would have dominated the otherwise vertebrae-like Discovery‘s structure like giant butterfly wings. Even the decidedly non-nuclear fuel-cell-powered Shuttle and solar-cell-powered ISS sport sizable radiators to dump the heat of their electricity-powered hardware. Ordway and Lange were quite aware of the need for such radiators and appropriate models were built, but in the end aesthetics carried the day, so the cinematic Discovery coasted along (silently) somewhat sleeker than known physics demanded. (One interesting tidbit here: some Glenn Research Center engineers redesigned the Discovery recently as an engineering exercise.(10))

Image Credit: Jon Rogers.

Cabin Interior

Speaking of sound, 2001 may be the only fictional film to convey the significant background noise in a spacecraft cabin. Every interior scene in Discovery is colored with a background hum, most certainly meant to be the many spacecraft systems running continuously, including air circulation fans. Crews have reported that the Shuttle cabin is a very noisy workplace, and some portions of ISS were once rumored to merit earplugs.

As already noted, the Orion III cockpit is remarkably similar to the Shuttle cockpit. One notes that all of the cockpits in the film are “glass” cockpits, where all information is displayed on computer screens (versus the dials and meters typical of 1960s technology). But this time it was the real-world Shuttles that caught up with the film (and a significant portion of the world’s airliners). During the 1990s the orbiter’s cockpit displays (including many 1972-era dials and meters) were entirely replaced with glass-cockpit technology.

Hibernation

Nope. Still can’t do that today. Suspended animation is an old story device in prose science fiction, not seen as much these days. About the only progress there is therapeutic hypothermia which may be a step towards ‘hypersleep’.

In fact, the Salyut, Mir, and ISS programs were geared toward keeping crew members active for longer and longer durations, not asleep. The concept of conservation of crew supplies is reasonable enough, but even in 1968 multiyear missions did envision years-long expeditions with enough self-contained logistical support. The sleep stations shown on Discovery, however, appear to offer crewmembers the same small volume as those on the Shuttle or ISS.

Communications

This is a technology that really tends to hide behind the flashier and more obvious equipment but is so critical that it should never be taken for granted. Unfortunately, by using it as a device serving the subplot involving HAL and the Discovery crew, Kubrick and Clarke committed a serious misstep in predicting the technology of today — er, yesterday. If you recall, the first sign of HAL’s neurosis is his false report that the AE-35 unit (the electronic black box responsible for keeping Discovery‘s antennae suite pointed at Earth) is going to fail. Mission Commander Dave Bowman must take a spacewalk to haul it inside after replacing it with a substitute. After finding nothing wrong with it, the crew (acting on the ominous suggestion of the erroneous HAL computer) decides to put the original unit back.

Here’s the problem: a system as critical as the communications pointing system would not have a single-point failure, especially in a manned spacecraft flying all the way to Jupiter! In fact, a Shuttle launch was scrubbed because one of two communications black boxes was not working properly. The Shuttle was designed with fail-operational fail-safe redundancy. In other words, if a critical unit fails, the shuttle can still support mission operations. If a second, similar unit fails, the shuttle can get home safely. Realistically, such a failure in a sophisticated Jupiter-bound manned spacecraft would call for simple rerouting of the commands through a backup unit, with at least one more unit waiting in reserve beyond that. This wouldn’t be a very dramatic turn, but such a sequence would better parallel the occasional Shuttle and ISS systems failures that have thus far been irritating but not showstoppers. (Of course, not all those many years ago Mir lost all attitude control when its one computer failed, so perhaps the premise isn’t too far fetched…) Once again, though, this technical ‘glitch’ was dictated by the cinematic narrative. Is it not interesting, however, that our premier unmanned Jupiter probe, Galileo, suffered a crippling failure of its primary communications antenna?

On the spinning space station, Dr. Floyd makes an AT&T videophone call to his daughter. Today’s space station inhabitants do, in fact, converse with their families over a video link, but it’s reasonably certain that their calls don’t cost $1.70 and get charged to their calling cards.

Spacesuits & EVA

This is the issue wherein 2010, that bastard child, really makes “hard” science fiction fans hang their heads low. 2001 presented spacesuits (especially those on the Jupiter mission) that were sophisticated, logical in design, quite impressive in capability, and perfectly believable for an advanced space program. 2010‘s American spacesuits look like they rolled off the EMU rack at Johnson Space Center!

The single component of the 2001 suits worn by Dave Bowman and Frank Poole most analogous to the EMUs today is the built-in jet maneuvering pack. Small, unobtrusive, minimal — that pretty much sums up the SAFER unit developed for station EVA. The 2001 suit does reflect the modularity concept of the Shuttle-era suit as well: helmet and gloves attach to the main suit with ring seals, but Ordway and Lange did not anticipate the move towards “hard shell” design (the American suit’s rigid torso, the Russian back-door-entry Orlan). The cinematic suits appear much more akin to the old Mercury and Gemini configurations, or even the recent advanced design of Dr. Dava Newman at MIT. (Note 3)

One notes there is a glaring design failure in the Discovery EVA suits. There is an external oxygen hose from helmet to backpack. This does not exist in Harry Lange’s initial suit designs and that hose does not exist on Heywood Floyd’s suit and the other suits on the visit to the Lunar Monolith. It was a bit of cinematic drama that could have been taken care of with a suit tear, a rare oversight by Kubrick. Real space suits just don’t have a vulnerable oxygen supply tube from the backpack EMS unit to the suit helmet (we see Frank Poole fighting to reattach his). Even in 1965 Apollo space suits had much more secure fittings.

While not a matter of technical prognostication, we can’t help but mention that the EVAs shown in 2001 remain the most realistic fictional depiction of spacewalking ever put on film. (That is, until the 2013 film Gravity.) The fluidity of motion and the free-floating grace of the crewmembers as they move completely in line with real physical laws is nearly identical to what you see downlinked on NASA TV. Not impressed? Compare Bowman’s approach and arrival at the Discovery‘s antenna in 2001. How’d Kubrick pull it off? Skilled stuntmen suspended from cables filmed from below—that was the key. Filming at high speed and then slowing the footage for incorporation in the film also helped. (In Apollo 13 extensive use was made of flying parabolic arcs in a Boeing KC-135 — that was real zero g. Alfonso Cuarón used ‘motion capture’ and computer generated imagery in Gravity.

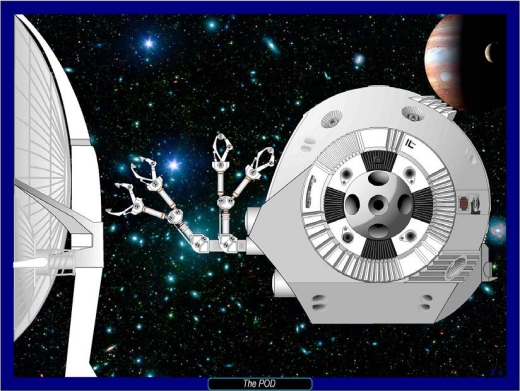

One EVA item in 2001 that today’s engineers and astronauts would love to have but don’t is the space pod: that ball of a spacecraft with the pair of multi-jointed arms out front. Such a vehicle would eliminate the need for some suited EVAs (the crewmember could just stay inside the pod) and would make others much easier (since the pod, under the control of the ship’s highly intelligent computer, could help out). But if you think about it, we’re really not too far off with the Shuttle and ISS remote manipulator systems (the Canadarms) These now (especially with the recent addition of DEXTRE with its two multi-jointed arms) permit the accomplishment of some tasks outside the spacecraft without EVA, and they have proven themselves capable EVA assistants under the control of a highly intelligent computer—namely, a crew member back inside the spacecraft cabin!

The most glaring difference in EVA, however, lies in protocol. During the EVAs in 2001, a single crewmember conducts the EVA. This is just not done today. Both Americans and Russians always leave their spacecraft in pairs (and in rare circumstances, as a trio) for safety’s sake — if one crewmember gets in trouble the other can come immediately to their aid. However, practically speaking, both crew members did have a companion: HAL the computer, controlling the space pod. But, of course, the solo EVA, the single-point communications failure necessitating the EVA, and HAL’s control of the space pod, collectively set up the greatest drama in the film: HAL trying to kill off all his crewmates.

Image Credit: Jon Rogers.

Artificial Intelligence

Given the many different levels at which the space program (and society as a whole) use computers today, it is within this niche that the film’s accuracy is most difficult to gauge.

Certainly, we have computers that can talk, and Shuttle and station crews have experimented with voice-activated controls of some systems, but these are superficial similarities. More importantly, we find a better comparison in the command and control realm: during large portions of a Shuttle’s mission, the fail-operational fail-safe primary & backup computer suite of five GPC computers did control the vehicle just as HAL completely controlled Discovery. (In fact, as a particularly curious side note, the programming language for the Shuttle’s primary computers is actually termed HAL/S, for Higher Assembler Language/Shuttle, but this just might be a not-so-subtle homage to the film by the software development team.) Unlike a lot of prose science fiction, 2001 did anticipate flat screen TVs and what seem to be IPADs!

The film was created at a point in history when the computer’s invasion of our society (including spaceflight) might have taken one of two paths: bigger and more powerful mainframe computers that would interface everywhere through an extensive but centrally controlled communications network, OR smaller and smaller special-purpose computers that each would do a little bit of the work. HAL certainly represents the pinnacle of achievement for the former — an artificial intelligence that had control of every single aspect of the Discovery‘s operations. The distributed PC network controlling the ISS today reflects the latter.

Yet the depiction of the HAL 9000 (Heuristically programmed Algorithmic Computer) in 2001 remains one of the film’s most eerie elements. For their description of artificial intelligence, Kubrick and Clarke only had the terminology and the vision of the mid-1960’s as their guide. At that time the prevailing concept expected ‘AI’ to be a programmed computer. Thus the term ‘computer’, with all its implications of being a machine, occurs repeatedly.

But in the last 50 years no true ‘strong’ AI has emerged. Today’s corresponding term would be ‘strong AI’ (11); their use of mid-1960’s terminology obscures the fact that Kubrick constructed an AI that is unmistakably ‘strong’, that is, capable of “general intelligent action.” How this would have been achieved Kubrick and Clarke left to the imagination of the viewer and the reader.

As HAL seems to be a ‘strong AI’, capable of feeling, independent thought, emotions, and almost all attributes of human intelligence, anyone viewing the film today should forget the film’s and novel’s use of the terms ‘computer ‘and ‘programming’. HAL seemed able to reason, use strategy, solve puzzles, make judgments understand uncertainty, represent knowledge including common-sense knowledge, plan, learn, communicate in natural language, perceive and especially see, have social intelligence, be able to move and manipulate objects (robotics), and integrate all these skills toward common goals. These attributes are possible not through programming as much as through ‘evolving’ or ‘growing-learning’ … a ‘solid-state intelligence’. That is why it is amazing to watch the film today (despite its use of clunky, ill-suited words like computer and program) and realize that HAL was a TRUE AI. HAL likely will exist in a universe which we have yet to realize, but one has no idea when! (See note 4.)

Some Reverse Engineering

From the moment we meet HAL we are given to believe that this particular AI has total control of everything in the Discovery. He can take action — open pod doors, open pod bay doors, even adjust couch cushions! — at a crewmember’s spoken word. Yet after HAL kills Frank Poole and the hibernating crewmembers followed by Dave Bowman’s return to the Discovery, what do we see? A manual, emergency airlock/entrance.

What is that doing there? Directly, to provide the film with an ‘action scene’, but the implications are deeper. Ordway/Lange of the Discovery knew their spaceships! A ship that substantial on an important mission must have redundancy; if not in the communications system, then at least to back up the onboard AI! Ordway wrote a memo to Kubrick about ship redundancy (7a). What if HAL had been ‘holed’ by a very freak meteor hit? What if an ultra-high-energy cosmic ray bored a damaging track through one of HAL’s solid state modules? Any of a number of possible unpredictable second- and third-order failures might occur, so the crew might be forced to take care of the ship and mission ‘on their own.’

And it is here, in the consideration of backup systems, where we catch Kubrick and Clarke, the storytellers, at odds with Kubrick and Clarke, the prognosticators of realistic spacecraft design. We find Bowman and Poole discussing how to partially shut HAL down by leaving only primitive functions operating. That could only be an option if the human crew could control the Discovery manually (or rather more practically, semi-manually) with a lot of help from still-working automated systems. This issue is more explicit in the movie and implicit in the film.

In fact Kubrick mildly trumps Clarke technically and dramatically in the film’s narrative structure (wherein Bowman leaves the ship to rescue Poole, setting up the emergency airlock action scene). In the novel, Clarke merely has HAL ‘blow down’ the Discovery by opening the pod bay doors. However, examining Lange and Ordway’s drawings of the Discovery‘s living quarters reveals at least two airlocks between the pod bay and the centrifuge (7,7a,8,9). Independent double and triple overrides (over which HAL had no control) would have come into play to prevent this very scenario from happening, mechanically or insane-AI-instigated.

How about HAL’s control of Dave’s pod? Actually one can capture a frame in the pod (‘N/A HAL COMLK’) that shows that Bowman, even though he left his helmet behind, had the sense to cut HAL’s control of the pod. It is impressive but not surprising that Kubrick and his team thought to include such a detail.

When Comes the Future?

While Kubrick and Clarke’s iconic 1968 vision of spaceflight’s future may have been far off the mark in terms of how much we would have accomplished by the turn of the millennium, its accurate anticipation of so many operational and technological details remains a fitting testament to the engineering talent of their supporting players, especially Fred Ordway and Harry Lange. The astounding prescience in their projections of the specifics of space operations decades beyond the then-current real spaceflight of Gemini and Apollo, even when constrained by storytelling aesthetics, offers the promise that their spectacular rendering of a spacefaring society may still come to pass.

With the United States and other nations now finally developing systems to return human crews to the Moon and enable travel beyond, and with commercial entities actively pursuing private spaceflight across a spectrum of opportunities long considered a matter of fantasy, perhaps we can take heart in the possibility that by the time another fifty years have passed, Kubrick and Clarke’s brilliant, expansive, and yet convincingly authentic future may finally become real in both its details and its scope.

Selected Bibliography

(1) 2001: A Space Odyssey, by Arthur C. Clarke, based on a screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke. Copyright 1968. The New American Library, Inc.

(2) The Making of Kubrick’s 2001, edited by Jerome Agel. Copyright 1970 The Agel Publishing Company, Inc. The New American Library, Inc.

(3) 2001: filming the future, by Piers Bizony. Copyright 1994. Aurum Press Limited.

(4) The Lost Worlds of 2001, by Arthur C. Clarke. Copyright 1972. The New American Library, Inc.

(5) The Odyssey File, by Arthur C. Clarke and Peter Hyams. Copyright 1984. Ballantine Books.

(6) “2001: A Space Odyssey,” F.I. Ordway, Spaceflight, Vol. 12, No. 3, Mar. 1970, pp. 110-117. (Publisher: The British Interplanetary Society).

(7) Part B: 2001: A Space Odyssey in Retrospect, Frederick I Ordway, III Volume 5, and American Astronautical Society History Series, Science Fiction and Space Futures: Past and Present, F.I. Ordway, Edited by Eugene M. Emme, 1982, pages 47 – 105. (ISBN 0-87703-173-8).

(7a) Johnson, Adam (2012). 2001 The Lost Science. Burlington Canada: Apogee Prime

(7b) Johnson, Adam (2016). 2001 The Lost Science Volume 2. Burlington Canada: Apogee Prime.

(8) Jack Hagerty and Jon C. Rogers, Spaceship Handbook: Rocket and Spacecraft Designs of the 20th Century, ARA Press, Published 2001, pages 322-351, ISBN 097076040X.

(9) Dieter Jacob, G Sachs, Siegfried Wagner, Basic Research and Technologies for Two-Stage-to-Orbit Vehicles: Final Report of the Collaborative Research Centres 253, 255 and 259 (Sonderforschungsberiche der Deutschen Forschung) Publisher: Wiley-VCH (August 19, 2005).

(9) Realizing 2001: A Space Odyssey: Piloted Spherical Torus Nuclear Fusion Propulsion NASA/TM-2005-213559 March 2005 AIAA-2001-3805.

(10) Searle, J. (1997). The Mystery of Consciousness. New York, New York Review Press.

(11) The film 2001: A Space Odyssey, premiere date April 6 1968.

Notes

(1) Acknowledgments: Thanks to Ian Walsh, Jack Hagerty and Wes Kelly , personal communications. Also, Special thanks to Douglas Yazell and the Houston section of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics for hosting the first edition of this article in 2008.

(2) In the mid 1960’s many of the SETI pioneers were afraid that revelation of the existence of an advanced extraterrestrial civilization might cause a social disruption; many others disagreed with this. Kubrick and Clarke decided to keep this as a plot device.

(3) There is an amusing bit of homage to George Pal in the film. In the 1950 movie the commander’s suit is red, the 2nd in command has a yellow one, all the rest are blue. Same is true in 2001! [8]

(4) The novel 2010 explains HAL’s ‘insanity’ in terms of his keeping the discovery of the TMA-1 monolith a secret for reasons of national security. (note 2) (Whatever that means.) This contradiction against his programming to never report erroneous information created a “Hofstadter-Moebius loop,” which reduced HAL to paranoia. Since nothing explicit is presented in the original film, and taking the characterization of HAL as a strong AI (for all intents and purposes making him ‘human’), HAL could have just as well gone bonkers for no good reason at all!

(5) A technical point about the emergency entry into the Discovery. Where did the pod hatch go? One notes that the pod doors slide ‘transversely’, i.e., they don’t swing in or out. In the airlock entrance scene Dave launches himself from ‘frame right’; normally the pod door slides open toward frame right (we’re seeing the rear of the pod in the scene). Thus the door’s guide track ran on both sides of the pod’s hatchway. Thus the normal open/close mechanism wouldn’t have to be retracted out of the way in an emergency. The pyros would be on the attach points where the door joins the mechanism, and in an emergency they’d blow the door further around the track, i.e., ‘frame left’, out of the way, while the regular mechanism stays put. (Thanks to Jack Hagerty for this observation.)

(6) 2018 is also the 30th anniversary of the viable ‘traversable wormhole’ by Morris and Thorne, this gives the ‘Star Gate’ in 2001 some physics which it did not have in 1968. M. S. Morris and K. S. Thorne, “Wormholes in spacetime and their use for interstellar travel: A tool for teaching General Relativity”, Am. J. Phys. 56, 395 (1988).

NASA is planning another manned space station in cislunar orbit. And STILL no centrifugal gravity :(

NASA has, according to a source on The Space Show recently, determined that 2 hours’ exercise 6 days a week adequately protects astronauts, based on the time it takes for them to recover normal neuro-muscularature after return to Earth, even for year-long stints.

The issue of exercise needed to prepare for Lunar or Mars gravity wells is undecided at this point.

The problem is not limited to neuromuscularity. There are cardiovascular changes as well. Contrary to popular thought, the long term physiological effects of zero-g have not been fully investigated.

I am not certain who’s popular thought this is contrary to, but this NASA book from 2012 makes it pretty clear how much we have yet to learn in regards to human physiology in space:

https://centauri-dreams.org/2012/09/11/the-psychology-of-space-exploration-a-review/

Only a very few people have been in space for over one year at a stretch. Only a handful have gone past Earth orbit to the Moon and that last happened in 1972 and for only a few weeks at most. No worlds have been colonized yet and no human has been born in space.

The crew stays on the Deep Space Gateway / Lunar Orbital Platform are not supposed to last more than a month at a time, so there is no need at present for artificial gravity on the LOP. Of course, this habitat is supposed to be a test bed for travel to Mars, which _will_ take longer than a month, so this issue has not been resolved, just kicked down the road at little.

This NYT article from March 30, 2018 taught me a number of things about how Kubrick chose the voice for HAL 9000:

https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/30/movies/hal-2001-a-space-odyssey-voice-douglas-rain.html

Just like now iconic soundtrack, Kubrick went with a totally different voice actor towards the end of film production after another actor had already done al of HAL’s lines. In both cases it turned out to be the right choice but I can only imagine what the original folks felt like.

An excellent piece on 2001 to all concerned and I will add my two thousand and one cents in a while.

This issue is more explicit in the movie and implicit in the film.

film vs. movie?

If you mean we don’t speak about the film’s story narrative , yes that is intentional , there are books written about that.

I had always wondered if Kubrick originally wanted to do Clarke’s Childhood’s End. In the book Stanley Kubrick: A Biography by Vincent LoBrutto (1998) he says that Kubrick’s was interested in that Clarke novel but never says what happened about getting the option was a problem or if Kubrick’s changed his mind. In Clarke’s Lost Worlds of 2001 he has a diary entry , when writing , (he would write the novel and give pages to Kubrick who would write the screenplay with a ton of give and take every day when they were in New York) he had an entry about Kubrick asking Clarke to make the ‘monolith makers’ the Overlords. Nothing came of that but the end of the film does seem an abstracted shadowing of the ending of Childhood’s End.

Future space tourist will probably want to travel into space to experience a microgravity environment. But there could be a huge economic advantage if personal maintaining and managing microgravity habits could stay in simple– artificial gravity– habitats orbiting nearby when the microgravity habitats were unoccupied.

A simple linear rotating space station with pressurized habitats located at each end, could comfortably accommodate astronauts in orbit for several months or several years under perhaps 0.5g of simulated gravity. Such artificial gravity habitats (perhaps 65 tonnes in mass) could be deployed to LEO with a single super heavy lift vehicle launch.

That would mean you wouldn’t have to launch space station management and maintenance personal every time you transported tourist into space. This would allow a lot more seats for paying tourist– making a lot more money for private space companies involved in the space hotel business.

Artificial gravity habitats would also be economically advantageous for governments that want to have a continuous military presence in space without the expense of having to transport military personal to and from orbit every few months. Instead, military personal could stay in orbit for years without any deleterious effects to their health before returning to Earth.

Marcel

We still have to deal with the effects of radiation that does degrade the body. My guess is that this will initially be mitigated to some extent by drugs that improve DNA repair, increase apoptosis, and improve the immune system to reduce the chances of cancers developing. But the damage to cells will accumulate.

Clarke’s books even until 1968 have no mention of the radiation hazard in space, even though the Van Allen belts were discovered in 1958 and the hazard was known, although the effects could only be speculated based on existing knowledge of em radiation and the atomic bomb.

Easier to just use reserve water as a spherical shell. Safety for radiation demands 6 m column length water, so a 1oo m sphere with 6 m column length water means 100,000 tons–& you have a big orbital hotel. A thousand BFR launches & you’re done.

That should keep room prices nice and high to keep the riff-raff away from the superwealthy elites. ;)

It also suggests that budget hotels should source their water from elsewhere, like Ceres. Electric or solar sail propulsion would be a good solution to fly those icebergs back to cis-lunar space.

Who knew that the space hospitality industry would be so difficult?

Why on Earth (er… space) wouldn’t you get all of that water from in space? I think a shell 1 – 2 meters think would actually suffice, but, either way, water extraction and a solar sail barge at an asteroid would IMO make more sense.

Clarke was definitely an optimist where radiation was concerned. In “The Promise of Space,” he wrote (after discussing how zero g [the term then] turned out to not be dangerous for up to several weeks, at least, and then mentioning the possible need for “storm cellars” aboard interplanetary spaceships), “judging by the way the other space bogeys have evaporated, no one will be surprised if solar flares turn out to be more spectacular than dangerous.” Regarding “2001: A Space Odyssey” (the film, at least [I haven’t read the novel]):

The scene in which Dave Bowman made the “vacuum-dive” from the pod into Discovery One had one, and possibly two, errors:

He held his breath before blowing the pod hatch, which would have invited lung ruptures (breathing deeply to infuse as much oxygen into the blood first, then letting his lungs empty to vacuum before jumping, would have given him up to about 15 seconds of useful consciousness without risking burst lungs–enough time to slam the airtight hatch shut. Also:

Before Dave Bowman could have manually opened the emergency airlock hatch to make his jump from the pod into the ship, HAL could have fired Discovery One’s attitude control thrusters (and/or engaged her reaction wheels, if any) to rotate the ship, making such a manual ingress impossible. Maybe HAL figured that Dave–not having his suit helmet–either wouldn’t try it, or would fail in the attempt, or perhaps HAL, being human-like, felt guilt for his murders and decided to let punishment befall him (like how some criminals, if their consciences overcome them, deliberately make mistakes so that they will be caught)?

Ever see the 1982 documentary The Atomic Café? The dangers of radiation were downplayed right into the 1960s, both from lack of knowledge on the subject and from deliberate manipulation of the data. Clarke was no doubt influenced by this, with maybe a dollop of wishful thinking added.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Atomic_Cafe

There was also a lot of fear about radiation too, well expressed in movies, especially in the 1950’s. “Mutant bug” B movies were endemic. (I still like “Them” and watch it occasionally).

That is always the problem, people reacting to such things either at one extreme or the other rather than trying to do some homework and working their way towards the middle ground.

Because the military and politicians downplayed the dangers of radiation, they contributed to the extreme reaction in the other direction which has hampered utilizing nuclear power in good ways.

This in turn is one reason why we have not yet had a nuclear-powered spaceship despite all the progress we were making fifty-plus years ago.

No, but I *have* heard of it, thanks to the Conelrad website http://www.conelrad.com/index.php , which covers the frequent downplaying of the dangers (including from the atmospheric nuclear bomb tests, for which the winds “always blew in the right ways…”).

And to think Clarke had written so many times about being able to survive briefly in vacuum, even including it in his early short story, “Take a Deep Breath” (1957) in “The Other Side of the Sky”. This scene had to be Clarke’s idea to demonstrate this idea.

Curious thing that Clarke did not use what in the film in the book, not clear why. I remember once looking up the ‘how long to survive in a vacuum’ question. I seems to depend on your body mass but a rough estimate is about 60 seconds. I have never put a watch on the sequence in 2001 but it is less than that. Knowing the way Kubrick worked Ordway probably had a memo for him about it, I know studies had been done.

”This path was chosen for two reasons: A rotating spacecraft’s structure must be significantly sturdier (and thus more massive, and thus more expensive to launch) to handle the stresses of spinning, and the utility of zero g seems to outweigh its negative aspects.”…..

What stresses ?

Anything sent to space have to handle much bigger G-forces for launch , and much bigger structural demands for containing pressure.

Utility of zero G ?

The rotating part would be ofcourse be for living quarters where zero g have no advantage .

These two statements only makes sense as an expresson of the stubborn refusal to admit a strategic mistake , the kind which can be seen in countless organisations ,whereever effective compettion has been walled off . ..and so we must wait for Elon Musk or the Chinese to provide this competition before the Dinosaurs can be remooved

I have liked the explanation Dr Chandra gives in the movie version of ‘2010’:

“HAL was told to lie… by people who find it easy to lie. HAL doesn’t know how, so he couldn’t function. He became paranoid.”

HAL gets rid of the crew so he doesn’t violate his basic programming: tell the truth always and don’t hold anything back.

Here is a thought: Suppose HAL 9000 succeeded in bumping off all the human crew members of Discovery 1. What would he have told Mission Control what happened? The truth? Or that some accident befell all five of them and he had to take over as HAL was programmed to do in the event of a crisis?

Did Discovery 1 have the equivalent of some kind of “black box” that would automatically record every moment of activity and function aboard the spaceship? Would Mission Control have some way to remotely access its data, since if a disaster happened to the ship in deep space there would be virtually no other way to recover it to find out what happened, at least not any time soon? Would this black box be tamper proof, or would HAL with his prodigious capabilities be able to hack it and reconstruct the data in his favor?

Even if the folks back home had no way to directly find out what happened to the Discovery crew if HAL’s plot had worked, their suspicions had already been raised by HAL’s mistake with the AE-35 unit – although I think it is remarkably absurd that they thought all HAL units were “foolproof and incapable of error.” Talk about tempting fate.

If Mission Control did suspect HAL had committed foul play, could they remotely take over control of the spaceship and/or shut down HAL? Even if they had this unreasonable faith in their “infallible” AI, would they not have had some contingency plan to remotely take control of Discovery in case something went really wrong across the board?

One big reason for such a remote control plan would be in case the nuclear-powered ship might have ended up on a collision course with TMA-2, a.k.a Stargate. I am sure the powers-that-be on Earth would not want to do anything that might seem like a hostile act against an obviously more advanced and powerful alien species.

Here is another related question I have had about 2001 for a long time: How would HAL 9000 have carried out the mission with the bigger Monolith around Jupiter (or on Saturn’s moon Iapetus in the novel)? The aliens were clearly expecting an organic human being to come through the Stargate: They even had a big blue luxury apartment set up for him. Would HAL have driven the entire Discovery through the Stargate, or sent in a pod as a proxy (which he did have control over, at least on this side of the gate)?

Lots to speculate here. Might make for a very interesting video game too.

A note: Dialog with HAL in the BBC interview almost makes it sound like HAL has total control of the Discovery.

Well , Frank and Dave talk about the procedures to be taken (they must have trained for it) of how of ‘disengage’ HAL. Also there is that manually operated emergency entrance.

In Lost Science of 2001 , in the refs, there is a memo from Ordway to Kubrick that the Discovery has to have backup and redundant systems. Ordway and Lange worked very hard on the technical aspects of the film. The book about Lange’s technical concepts is amazing. Only about 25% of the stuff Ordway and Lange came up with made it to the movie. It is not even known how much background documentation they did.

According to Frank while he and Dave were talking in the pod, HAL did have access to and control of just about every part of Discovery, with the obvious exception of the manual airlock. And as was noted in the article, Dave could and did take control of the pod from HAL.

As I said earlier, I just wonder if Mission Control had any way to remotely take over Discovery in case the crew were incapacitated, which would include HAL. Because otherwise you have a big nuclear-powered spacecraft plunging through space with no one at the helm and a mysterious alien artifact that might be in its path.

The film sequel 2010 made explicit what was certainly not clear in 2001 but discussed in the novel about HAL not being able to handle lying to the awake crew about the real mission of Discovery. To me that almost seems like a McGuffin: Could they not have put something in HAL’s programming which circumvented such seeming contradictions, if for no other reason than to tell HAL that the awake humans could not know about the alien artifact at Jupiter for their own safety?

Because thanks to HAL’s portrayal, we have been left with old trope that AI will automatically go bonkers and either try to control or kill humanity just because that is its “nature”. Same goes for aliens, which in fiction either want to save or destroy us because that’s what aliens supposedly do. People are already ignorant and paranoid enough about these subjects without adding fuel to the fire.

I read the story that Isaac Asimov saw 2001 with Clarke and began ranting in the theater that HAL broke his Three Laws of Robotics, which are all about machines not allowing a human to come to harm above all else. Is this a true story?

Somewhere , can’t find the reference, Clarke did note that he and Asimov has a conversation about ‘Laws’ and HAL , as I remember Clarke told Asimov that HAL’s AI-ness took him beyond programmed Robot intelligence, so to speak.

You know there are two paragraphs early in the novel describing HAL”S ‘intelligence’ as having been evolved, not programed. Clarke has to frame the argument a little abstractly but I think he got it from Minsky.

That is interesting. Minsky was a symbolic logic advocate and was instrumental in undermining neural approaches using Perceptrons (they could not handle XOR conditions). Neural systems evolved to neural networks and to the deep nets of today.

Paradoxically, Minsky also wrote “The Society of Mind” which looks rather more bio-inspired and neural to me even though it is just conceptual.

The Space Shuttle GPCs’ software was certified as error-free, the only software in the world which, to my knowledge, was so certified. This is a far cry from HAL 9000, of course, but it suggests that such a state of affairs in an AI computer might be possible. I doubt, though, whether such a computer–which could argue back, balk, or even engage in mutiny–would ever be placed in control of a manned spaceship, as that would be asking for trouble, but:

In cases where such a computer would be the only solution, they could be employed. AI computers would be ideal for robotic interstellar messenger probes (Bracewell probes), which must think for themselves and decide what to do (because the signal time delays would make Earth control impossible). Digital AI computers may not be practical or even possible, but there is another possibility for creating such machines:

Rupert Sheldrake, a British biologist, has pointed out that analog computers “enable complex, self-organizing patterns of activity to develop through sometimes chaotic, oscillating circuits.” He also noted that in 1952, William Ross Ashby, a British cybernetics researcher, published a book titled “Design for a Brain,” in which he showed how analog cybernetic circuits could model brain activity. More recently (as Sheldrake also noted), Mark Tilden developed insect-like robots that demonstrated self-organization—and even learning and memory—despite the fact that these devices contain fewer than ten transistors and have no computers in them, and:

BEAM (Biology Electronics Aesthetics Mechanics, or Biotechnology Ethology Analogy Morphology) robotics, a “reaction-based” type of machine building, was inspired by Tilden’s work. (In the nearer term, analog logic circuits-containing robots such as Tilden’s would be useful as rovers, “hopper” rovers, winged and aerostatic aerobots, instrumented boats, and submersibles for exploring planets, moons, asteroids, and comets in our own Solar System. In the future, stellar rendezvous starprobes could deposit similar robots on the worlds orbiting their target stars, and relay the robots’ findings to Earth.) In addition:

A network of such analog devices might also possibly (perhaps in combination with some digital subsystems) function together to form a type of STAR (Self-Testing And Repairing) computer, which could control interstellar spacecraft. Since about 1961, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory had conducted research on a digital STAR onboard computer, which later in that decade found favor for the planned four-spacecraft Grand Tour mission, for which a non-flight “study model” called TOPS (Thermoelectric Outer Planet Spacecraft) was built. Kenneth Gatland, and the Soviet engineer B. Volgin (as is mentioned on page 244 of the former’s book, “Robot Explorers”), both discussed the need for interstellar spacecraft to have self-repairing computer systems that could also learn and make decisions for themselves.

HAL900 was a heuristic software design. I cannot see how it could never make a mistake. I suspect that the assumption was that Boolean logic that is deterministic and would have been encoded as an expert system would always produce the expected answers. We now know how brittle such systems are. If HAL was being designed today, it would certainly incorporate neural networks as part of its intelligence.

Perfect, foolproof computers are such an old idea, especially wrong if they are to exhibit AGI as HAL apparently does.

Maybe the algorithms could be inerrant, but their interactions could yield incorrect final results. Clarke, however, seemed to have accepted the possibility of error in such AIs. The Starholmer’s Bracewell probe in “The Fountains of Paradise,” called Starglider, functioned according to general instructions programmed into it ~60,000 years earlier (it had flown by several other stars before passing through our Solar System), and it made a few mistakes, although they were minor.

“The Fountains of Paradise” was published in 1979, long after the 1960’s technology euphoria wore off and deep into the pessimism of the 1970s. Clarke was learning the vagaries of computers from his Kaypro [?]. “3001: The Final Odyssey” (1997) has suggestions that the monolith was malfunctioning too. Funnily enough, we are in the midst of technology euphoria again, especially in AI. I’m waiting for the Gartner post-hype “trough of disillusionment” to reassert itself.

The 1970s were generally pessimistic when it came to space after the euphoria and then abandonment of Apollo, but the decade did spawn some very high-end space plans.

These included:

Project Daedalus by the British Interplanetary Society (BIS) with the concept of a nuclear fusion-powered interstellar probe run by a semi-intelligent AI (their words):

https://www.bis-space.com/what-we-do/projects/project-daedalus

The Space Settlement concept, which envisioned giant space colonies not on other planets but in huge artificial structures circling Earth at the LaGrange points:

https://settlement.arc.nasa.gov/

In their times Daedalus was considered possible by circa 2050, while the Space Settlements were touted as starting as early as the 1990s. An entire article in the July, 1976 issue of National Geographic Magazine was devoted to the concept, which was to be fully realized by 2026.

The nice thing is that after decades of unfulfilled promises we may finally be seeing all of our earlier space dreams come true. I was worried they might either never happen or happen far into the future.

2001 abounds with mysteries, there is one I have never been able to ferret out. There are notes in Clarke and Ordway’s remembrances of something about heated arguments at daily production meetings, however neither Clarke or Ordway is explicit about it.

Two bits of possible evidence. Hal’s deadly action in the novel differ from that in the film. In the movie HAL just does not let Dave back in, in the novel HAL opens the POD Bay doors and the airlock to POD Bay. Dave has to dive into a safety ‘locker’. Not clear why the narrative differs since Clarke keep revising the novel to the film story even when he was in Sri Lanka.

Further Kubrick never explains HAL’s ‘motivation’ in the film Clarke makes it explicit , well almost explicit, in the chapter Need to Know in the novel and later in 2010.

The main mystery is why did Kubrick call one the subject matter experts , on the film, to England to talk about AI and HAL again. That was AI expert Marvin Minsky. In the Legacy of Hal Minsky is interviewed and tells the story of meeting Kubrick and going to the set but not once does he relate what Kubrick wanted to talk about.

If I had only the film version of 2001 to go on, I would think HAL acted as he did because the astronauts were planning to shut him down for that one error with the AE-35 unit and this would have been a threat to the mission, for which HAL had the greatest enthusiasm. I did not get the impression that HAL was having some kind of internal conflict between telling the truth and lying.

Yes, there was that scene with Dave Bowman where HAL kept implying about odd things regarding the preparations for their mission, but it was pretty obvious that Dave did not catch on to any subtext in HAL’s comments. I would have interpreted this scene as HAL trying to point Dave towards the real reasons they were flying to Jupiter without breaching security, but up front I would not have picked up on this being a serious conflict for the AI.

The reason would be what I said earlier, that the safety of the human crew would have been paramount for HAL for the success of their mission and their not knowing about the alien intelligence was deemed mandatory by the folks in charge back on Earth.

Now going back to other sources, the 2001 novel stated that HAL considered being shut down tantamount to a death sentence, since he never even slept, so the astronauts’ clearly sneaky behavior in the pod could only be interpreted by HAL as a murder plot, which in turn would have threatened their mission, which was too important for them to jeopardize.

So HAL can’t lie but can figure out how to kill? And HAL apparently can communicate with a super alien intelligence who also didn’t bother to stop the killing. That’s as illogical to me as is the concept of true artificial intelligence. I’m not sure why people, actually believe that’s possible but maybe it’s a product of believing that humans are mere machines so naturally then one can assume a conscience intelligent machine is possible. Still, it was an all time great movie.

HAL/Bowman doesn’t ever really communicate with teh monolith builders, although in their combined Halman state they do partially understand how the monolith works.

Lying is rather different than killing. It requires deception and, to some extent, a theory of mind. Killing is purely operational, and in HAL’s case, analogous to the paperclip problem of intelligent agents.

It does seem to me that HAL could be trying to lie when he tells Bowman that he is now well again and able to function. The lie is so transparent that it hardly seems like a lie.

That HAL might have even seriously considered his “reassurances” to Dave about getting better would somehow placate the astronaut just shows how bad the AI’s neuroses had gotten by then – and perhaps the limits of HAL’s abilities to understand his human coworkers.

Though as we have seen with later chess playing computers in our reality, they can analyze literally billions of moves against their human opponents. One might think that an Artilect as sophisticated as HAL would be able to do the same and even better, but if the whole neurotic thing is true, then HAL’s decision making functions may have been even more degraded. I may even be borrowing this from the Star Trek episode The Ultimate Computer with M-5, but might HAL have felt some form of guilt for killing and attempting to murder the very people he was supposed to support and protect and thus his belated attempts to placate Dave?

As I stated earlier in this thread, if HAL 9000 had succeeded in killing all the humans on Discovery, what would he have told to Mission Control as an explanation for all five men suddenly dying? Would he have kept lying or would he have told them the truth with the explanation that their actions threatened him and therefore the mission? And what would MC have done in response? Surely they would have been less than thrilled that a homicidal and mentally unstable machine in control of a big nuclear-powered spaceship would be the sole Earth “ambassador” to an unknown alien power.

That the room containing his logic circuits could not be kept locked and sealed off by HAL himself may also indicate that those who designed and built HAL and Discovery may not have fully trusted the artificial intelligence despite its series previous track record.

To add to the above: It was pretty obvious that HAL did not feel (or at least did not consciously realize) any remorse when he thought Dave was going to be left trapped in the pod with no way back into the Discovery.

Just listen to how the tone in HAL’s voice changed when Dave famously asked him to “open the pod bay doors”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSIKBliboIo

So HAL’s reaction once Dave did get back in and was clearly heading for his “brain” with a singular purpose may have been little more than a last-minute appeasement to stave off the inevitable.

As a purely academic exercise, I wonder if HAL had any other measures at his disposal to stop Dave or any other human from attacking his logic center? He could have vented all the ship’s air like he did in the novel version, but Dave only made his mistake of forgetting his space helmet just once. Cutting off all the ship’s power or at least life support might have worked if HAL could also have locked his brain’s door, but that room had manual access. Note that HAL could also not lock any of the doors between Dave and his brain room, otherwise I am sure HAL would have sealed them off.

I also have no idea if there was any way to “self-destruct” Discovery, but that would have been a bit extreme in any event.

I saw on one blueprint that the habitation section of Discovery could be explosively disconnected from the rest of the ship, probably in the event of a nuclear emergency, but I am not certain if that would do much good in terms of HAL saving himself from the wrath of Dave.

That’s analogous to the ‘grey goo’ problem in nanotechnology where nanoscale replicators turn everything into more nanoscale replicators. Only the replicating machines were mindless robots merely following programming. We don’t even need AI to do real damage……

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grey_goo

Another place where 2001 took artistic license over reality was in the depiction of the lunar landscape itself. While not quite the jagged peaks that Chesley Bonestell and most other space artists both before and after him depicted the appearance of lunar mountains, the Moon’s surface in 2001 was a lot rougher than what we have since come to know it as.

The original thinking was that since there was no atmosphere and therefore no actual climate on the Moon, the lunar mountains would be uneroded peaks left virtually untouched since their creation. What they did not count on was that the face of the Moon was affected by erosion, but instead of wind and rain it was due to meteoroids of various sizes over eons. This is why the mountains as seen by the later Apollo missions which landed in the lunar highlands are all smooth and rounded; they also look deceptively like low hills. Some of the Surveyor missions which landed within camera view of mountains also revealed them to be smooth rolling hills rather than dangerously pointy.

Now I know the makers of 2001 knew the true nature of the lunar mountains because Arthur C. Clarke of all people authored a book from the Time-Life Science series titled Man and Space, first published in 1964. In it is a graphic showing that the lunar mountains are smooth and round rather than jagged points for the very reason I stated above.

So Kubrick et al did know what the lunar surface generally looked like even before the first machines with working cameras landed there, but I am guessing that because 1960s pre-Apollo audiences were so used to seeing the Moon as craggy and sharp (like in Destination Moon from 1950), they opted to go with the old-fashioned look.

I cannot believe I forgot to add this tidbit: I once wrote to Clarke about Man and Space and he mentioned in his reply that he was moonlighting with that book while working on some little space film at the same time….

There are essays about ‘physics mistakes’ Kubrick made in 2001 , especially some zero g ones. Kubrick would get 998 things right and be condemned for nits. (Not talking about the lunar landscape here.) Interesting one is the heat radiators on the Discovery , Kubrick understood very well the engineering physics but aesthetics trumped.

I wonder, Al, if a lot of astronautical engineers, astronomers, and space scientists find science fiction movies–even “2001”–difficult to watch (being unable to suspend disbelief so that they can simply enjoy them, that is) because the errors and omissions are so obvious to them? Carl Sagan could never get into “Star Trek” for that reason (“Thoughtful friends tell me I should enjoy it as allegory”), and my father–a fire chief–could never enjoy the 1970s action/adventure series “Emergency” (which was about firefighters and paramedics) because so many errors jumped out at him.

It really depends of how sensitive one is of small errors. Don’t know many technical people who had that kind of problem with 2001.

Can tell you that among science fiction reading fans in 1968 2001 was a step function. We had watched some good SF films in the 1950’s , Destination Moon to Forbidden Planet, but then we were swamped by Queen of Outer Space to Plan Nine from Outer Space , gad! many others …. so anything that might kill the Z SF film was welcomed.

That’s interesting; I had wondered if might have been a “left-brain thing” (being detail-oriented, which might hinder enjoyment of a technically-imperfect film), but I was just guessing. “Frakenstein Meets the Space Monster” is another of those unforgettable (unfortunately…) science fiction films. :-)

And yet, despite this, the illustrations on p142 & p144 by Ed Valigursky show quite a rugged landscape with fairly jagged hills without soft rounded forms. Those illustrations leave a far stronger impression than the earlier, tiny illustrations comparing the old jagged landscape conception with the new knowledge of softly rounded hills. Which is the visually more interesting is obvious, IMO. Kubrick probably made the decision on how to depict the Moon based on that. I believe that the decision to add stars even in a bright landscape was made because of prior audience expectations. What is space without bright, unwinking stars? The movie “Gravity” shows stars, even in a scene where the sun is facing the camera! At least the brightness of the stars is very reduced compared to earlier movies.

…And don’t forget the crater-free asteroids that are seen–briefly–in “2001” (I have a copy of “Man and Space” as well, and remember the lunar surface depiction discrepancies, although some “outlier” lunar locales are pretty rugged in real life). Until (relatively) recently, even astronomy books depicted asteroids without craters, and with radar, no spaceship would be allowed to pass so close to them (and the main belt zone is much, much more thinly-populated than most science fiction works depicted).

Don’t get me started on Gravity, an incredibly anti-space film which threw physics and logic out the window at its convenience.

If you ever watch “Land of the Giants” (Irwin Allen’s last [1968 – 1970] science fiction TV series, after “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea,”, “Lost in Space,” and “The Time Tunnel”), “Gravity’s” scientific fidelity may look exemplary by comparison. :-)

I know there are plenty of terrible science fiction films and television series which do not deserve to have the word science in their description.

What I really object to are those films which purport to be scientific and parade their science and technical advisors in the press, only to push them aside when reality gets in the way of their “vision”. Interstellar and Gravity are but two who are quite guilty in this area.

As bad as those series you mention above were, they did have a big influence on my interest in science fiction and real space science as a kid.

Excellent article.

There is a good review and critique of the computing systems in “HAL’s Legacy” ed. David Stork. In particular, designer Donald Norman critiques the computer displays as providing as a poor interface for humans.

I once tried to determine how realistic the Aries II Moon shuttle was in terms of fuel and propulsion for the lunar trip. IIRC, it was doable – just.