The detection of hydrogen sulfide just above the upper cloud deck of Uranus has received the nods you might expect to rotten eggs, H2S having the odor of such unappetizing objects. But this corrosive, flammable gas is quite an interesting find even if it makes a whiff of Uranian air more off-putting than it already was. Not that you’d live long enough to notice the scent if you happened to be there, as Patrick Irwin (University of Oxford, UK) is quick to note:

“If an unfortunate human were ever to descend through Uranus’s clouds, they would be met with very unpleasant and odiferous conditions. Suffocation and exposure in the negative 200 degrees Celsius atmosphere made of mostly hydrogen, helium, and methane would take its toll long before the smell.”

We can leave that excruciating end to the imagination of science fiction writers, among whom I want to mention my two favorite stories about this planet, Geoff Landis’ “Into the Blue Abyss” (2001) and Gerald Nordley’s “Into the Miranda Rift” (1993). And I always give Stanley Weinbaum full credit for the best Uranus story title of all time: “The Planet of Doubt” (1935).

Patrick Irwin is lead author on the paper discussing the H2S discovery, which is a significant one because it highlights the differences between the cloud decks on the two closer gas giants — Jupiter and Saturn — and the outer ice giants Uranus and Neptune. The former show no trace of hydrogen sulfide above the clouds, while ammonia is clearly present. In fact, most of Jupiter and Saturn’s upper clouds are laden with ammonia ice, a difference that can tell us much about the formation of the respective planets and their subsequent development.

Image: This image of a crescent Uranus, taken by Voyager 2 on January 24th, 1986, reveals its icy blue atmosphere. Despite Voyager 2’s close flyby, the composition of the atmosphere remained a mystery until now. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Leigh Fletcher, a member of the research team from the University of Leicester in the UK, notes that the balance between nitrogen and sulfur, and thus between ammonia and hydrogen sulfide, would have depended on the temperature and the location of the planet when it formed. These differences, in other words, are the signature of the gas giants’ formation history, adding to the evidence that the giant planets migrated from the position of their original formation.

Fletcher adds that when a cloud deck forms by condensation, most of the gas forming the cloud becomes embedded in a deep internal reservoir, putting it out of the view of our telescopes:

“Only a tiny amount remains above the clouds as a saturated vapour,” said Fletcher. “And this is why it is so challenging to capture the signatures of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide above cloud decks of Uranus. The superior capabilities of Gemini finally gave us that lucky break.”

Indeed. It took the 8-meter Gemini North telescope at Mauna Kea (Hawaii) to make the find, which the researchers achieved through spectroscopic analysis using the Near-Infrared Integral Field Spectrometer (NIFS), which sampled reflected light from a region just above the main visible cloud layer in the atmosphere of Uranus. Irwin describes these lines as being “just barely there,” at the outer limits of detection, but finding them in the Gemini data has solved a mystery of this planet’s atmospheric composition that persisted even through the Voyager flyby.

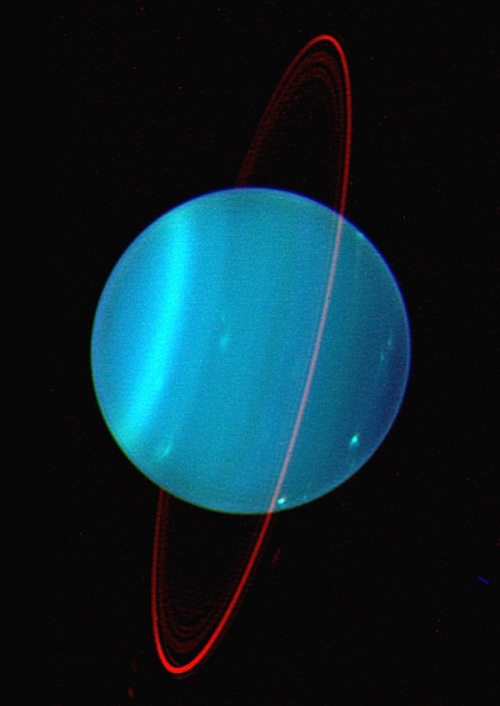

Image: Hydrogen sulfide is hardly the only interesting thing about Uranus. Near-infrared views of the planet reveal its otherwise faint ring system, highlighting the extent to which it is tilted. Credit: Lawrence Sromovsky (University of Wisconsin – Madison) / Keck Observatory.

Thus we finally identify a component of the Uranian clouds that it probably shares with Neptune, and the ‘planet of doubt’ takes us a little closer to revealing the secrets of the ice giants. The paper is Irwin et al., “Detection of hydrogen sulfide above the clouds in Uranus’s atmosphere,” published online by Nature Astronomy 23 April 2018 (abstract).

After being the butt of many a joke it looks like it was named quite appropriately.

Those stale and juvenile jokes are one reason we don’t have a serious mission being planned for Uranus. The other is that when Voyager 2 flew by the planet in 1986, Uranus appeared quite bland looking and only its moon Miranda captured any interest after all the spectaculars at Jupiter and Saturn – but then it didn’t have any active volcanoes or geysers or a hidden ocean of liquid water.

Here is a plan from 2013. Now that NASA is getting an increase in its budget and has an administration and congress that seems more favorable to space exploration and utilization in general, perhaps Uranus will have a chance despite all the odds against it.

http://futureplanets.blogspot.com/2013/07/uranus-or-bust-and-on-budget.html

Snowbank Orbit by Fritz Leiber involved Uranus in a cameo role; mostly as a airbag to slow down a space ship traveling well above solar escape velocity. The science was not bad for the era.

I remember that one and wrote about it in the archives here somewhere. It’s been a long time since I’ve read it.

A Uranus orbiter is long over due.

If you Google “Uranus,” the first Google-generated listing that appears under the search line, which I just saw, is “uranus stinks.” :-) Also:

“Journey to the Seventh Planet” (see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journey_to_the_Seventh_Planet and [trailer *and* full movie: http://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=journey+to+the+seventh+planet+full+movie ]) is a 1962 movie about a manned expedition to Uranus. Although it incorrectly depicted the planet as having a solid surface, it did portray what the cryogenic cold way out there would do to exposed human flesh (it isn’t too graphic, but the agony of that pain was well-acted–or at least it seemed so when I watched it 35+ years ago). The Uranian horse stable scene certainly strikes one as being incongruous, but such vivid mental imagery was generated in the minds of the (rather surprising, for a 1962 science fiction film) “co-ed” human crew, by an alien resident of the planet, and:

I have long thought that the ancient Greeks, from whom the planet’s name (“Ouranos,” [pronounced “OOR-ah-nos”] god of the sky [“Father Sky”] and son and husband of Gaea [Gaia], goddess of the Earth [“Mother Earth”], who first emerged from Chaos) originally came, by way of the Romans, would have found our “anatomically-referent” pronunciation of the Latinized version hilarious. Being unabashed, free and easy in such matters (shepherds and goatherds appreciated and honored Pan for teaching them how–during their long intervals of solitude while herding their animals–to pleasure themselves [as well as play the pan flute], to give just one example of many), they might well have thought, had they known, “*We* should have thought of that twist on the name!” :-) As well:

Jack Horkheimer, my late boss at the now-closed Miami Space Transit Planetarium, came up with a “less connotative” pronunciation of the planet’s name at the time of Voyager 2’s Uranus encounter (which some JPL folks also seemed to find a bit embarrassing, “P.R.-wise” [and the Challenger accident at that time didn’t help, as neither it nor the “planet name business” helped NASA’s public perception]). He called it “You-RAIN-us” when he referred to it in planetarium shows, in interviews, and on “Jack Horkheimer: Star Hustler” (his five-minute public television astronomy show [later renamed “Jack Horkheimer: Star Gazer” after internet search engine results began bringing up very unsavory websites–and not just for “Hustler” magazine–that contained the word “Hustler”]). This also brings up a remote, but not impossible, future situation regarding astronomical nomenclature:

With the gigantic number of exoplanets and their stars–and the all-too-finite, and increasingly “taken,” mythological names for these bodies, we are being forced to employ other names, which the exoplanets’ native intelligent inhabitants, if any (or future human colonists) might find insulting or embarrassing. For instance:

The relatively nearby star Mu Arae (? Arae), to give one (relatively mild) example, was named Cervantes, and its planets b, c, d, and e were given the names Quijote (Quixote), Dulcinea, Rocinante and Sancho, respectively. While this particular system isn’t thought to be a likely abode of LAWKI (“Life As We Know It”), what would any inhabitants (indigenous or Earth-colonial) of Rocinante–whose namesake was Don Quixote’s bony old nag–think of us? (I personally wouldn’t feel slighted, but others might well feel differently.) Now:

While this is certainly *not* anything I lose sleep over, if intelligent life turns out to be more common than we’re beginning to fear might actually be the case, the sheer numbers that could be involved might one day lead to undreamed-of (by “exoplanet namers”) interstellar diplomatic troubles (not a war, but perhaps less than cordial communication and less-than-full information exchange). For that matter, we might one day be nonplussed to learn what *our* Sun is called–and/or what part of the anatomy of God knows what kind of alien creature our home star represents–in some unearthly constellation… :-)

It should be subtitled “Joke Planet of the Universe!”

At least it may encourage some interest in space/astronomy:)

But it will not encourage exploration by planetary space probes as who wants to work on a project involving a world that is constantly mocked for its name? That mockery and those stupid jokes will only be transferred on to them. And no, I do not think I am exaggerating the situation here.

As for encouraging general astronomy, there are much better ways to do this than calling Uranus the “Joke Planet”. For one thing, no one can see Uranus with unaided vision especially in these light polluted times. And viewing Uranus through a typical telescope is nowhere near as exciting as seen Jupiter or Saturn, or Luna in particular.