How big a role space travel will play in our future is a question with implications for our civilization’s intellectual, economic and philosophical growth. It may even be the hinge upon which swings the survival of the planet. But as Centauri Dreams regular Nick Nielsen points out in the essay below, enthusiasts for spacefaring can overlook historical analogies that show us the many ways humans can shape their culture. Numerous scenarios swing into view. An interstellar future may not be in the cards, depending on the choices we make, which is why seeing space travel in perspective is crucial for shaping the exploratory outcome many of us hope to see.

By J. N. Nielsen

The Role of Spacefaring in Spacefaring Civilizations

What is, and what will be, the role of spacefaring in spacefaring civilizations? If we count the present human spacefaring capability as constituting a contemporary spacefaring civilization, the question can be partly addressed by assessing the role of spacefaring in contemporary civilization. There are several different ways in which we might measure the impact of our spacefaring capability on civilization as a whole, some of them easily quantifiable and some of them not so easy to quantify.

It would be relatively easy to quantify the economic impact of the space industry on the planetary economy. Economists do this sort of thing all the time. A little more difficult would be to estimate the impact on our civilization of technologies made possible by a spacefaring capability, such as the existence of GPS and Earth observation satellites. More difficult yet would be to estimate the impact of our spacefaring capability not as an industry or a technology, but as a cultural and social influence. The influence of, say, the “Blue Marble” photograph was profound, but how can we measure the impact? Are there ways to quantify the overview effect? Should we even attempt to quantify such things? Are qualitative changes in the nature of civilization resulting from qualitatively new experiences intrinsically unquantifiable?

Some of these measures would make our contemporary spacefaring capability quite important to human civilization, and some less so, but I don’t think that any of these contemporary measures would point to our spacefaring capability as being the central project of our civilization. However, when I think about spacefaring in relation to the future of civilization, I often implicitly assume that spacefaring would be either the central project of a civilization, or would play a crucial role in the central project. This now appears to me as an unwarranted assumption, and perhaps even a marginal condition for a civilization to adopt. As we will see, the analogue provided by our own civilization suggests that spacefaring will be a socially and demographically marginal effort, necessary to the economic infrastructure, but not likely to be pursued as an end in itself, at least not on a demographically significant scale.

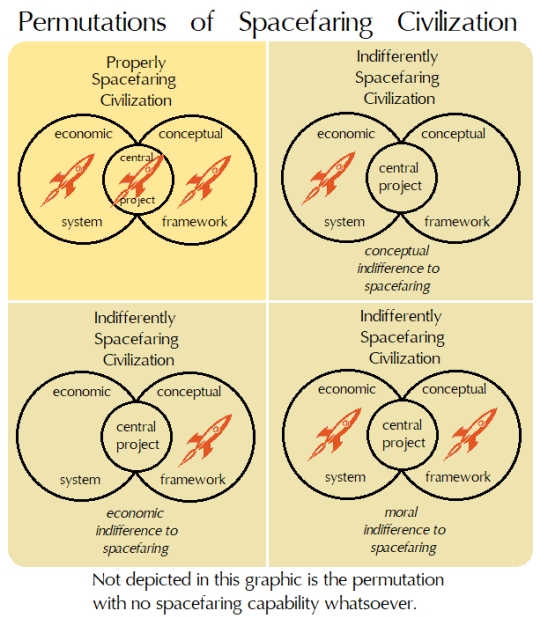

While I see our spacefaring capability as being interesting primarily for what it portends for the future, how it will shape human life and thought, it is entirely possible that our spacefaring capacity will continue to grow and to develop into a robust and influential industry that shapes the economic and technological future of our civilization, without at the same time dominating our civilization culturally or socially. [1] I will call civilizations that conform to this latter profile indifferently spacefaring civilizations. We can express the idea concisely in this way: an indifferently spacefaring civilization is a civilization with a mature spacefaring capacity, but for which spacefaring is not the central project of that civilization, nor is spacefaring integral to the central project.

Permutations of Indifference

In the model of civilization that I have been developing—according to which civilization is an economic infrastructure joined to an intellectual superstructure by a central project [2]—a spacefaring capability could be consistent with the primary role of spacefaring residing in either the economic infrastructure or the intellectual superstructure of a given civilization with indifference to spacefaring in the other, and with spacefaring absent from the central project. If, however, spacefaring is the central project of a civilization, neither the economic infrastructure nor the intellectual superstructure can be indifferent to it, though there may be subordinate institutions and groups within these structures that are indifferent to the central project and are pursing some other aim as an end in itself.

Spacefaring might also be integral with the central project without being identical to the central project. For example, a civilization that took the expansion of scientific knowledge as its central project, i.e., a properly scientific civilization, would rely heavily on a spacefaring capacity in so far as the scientific study of the universe beyond the confines of Earth would be a great epistemic challenge to a scientific civilization, and this challenge could only be pursued through spacefaring. Nevertheless, the focus would be the growth of scientific knowledge and not on the further development of spacefaring. Further development of spacefaring would come about indirectly as a result of pursuing further scientific research, or as a consequence of building larger scientific instruments than could be built on the surface of a planet.

If a civilization is in possession of a mature spacefaring capacity but does not have spacefaring as an integral part of its central project, we would expect that this mature spacefaring capacity would be integrated either into the economic infrastructure, the intellectual superstructure, or both. For example, spacefaring may be important in the economy of a mature civilization, but no more central to the project of that civilization than our contemporary communication and transportation networks are to our civilization. If you took away all our communication and transportation networks, our civilization would cease to function, so that our civilization is existentially dependent upon this economic infrastructure, but the same infrastructure does not define the core of our civilization. On the other hand, a civilization with an intellectual interest in questions that can only be addressed by spacefaring would involve spacefaring in its intellectual infrastructure, and, again, if you took away the spacefaring capacity, the intellectual inquiry predicated upon that capacity would cease to function, which could deeply comprise an advanced civilization; nevertheless, the central project is not defined in terms of the spacefaring capacity integral with intellectual inquiry. [3]

Indifferently spacefaring civilizations in which spacefaring is integral only to the conceptual framework could be said to be economically indifferent to spacefaring, while indifferently spacefaring civilizations in which spacefaring is integral only to the economic infrastructure could be said to be conceptually indifferent to spacefaring (or intellectually indifferent to spacefaring). In the case of spacefaring being integral to both economic infrastructure and intellectual superstructure yet absent in the central project, such civilizations could be said to be morally indifferent to spacefaring. We will consider each of these permutations of indifferently spacefaring civilizations in turn.

Economically Indifferent Spacefaring Civilizations

A civilization might be economically indifferent to spacefaring even while incorporating spacefaring as an integral part of its intellectual superstructure. Spacefaring could be significant for science, for art, for poetry and literature, and still be economically irrelevant if that civilization does not exploit its spacefaring capacity for economic growth and the development of economic institutions. [4] However, past human civilizations that have been economically indifferent to transportation have also been largely intellectually indifferent to transportation, so that it is difficult to produce an historical analogy for this permutation. This could be expressed such that economic indifference to spacefaring may entail intellectual indifference. For this there are obvious historical analogies.

A civilization economically indifferent to transportation would of necessity be a civilization of limited geographical (i.e., spatial) scope. Let us take, as an example, the civilization of early medieval Europe, after the collapse of Roman political and military power in western Europe, and before the crusades (we can adopt the approximate dates of 476-1096 AD, so this a civilization of about 600 years’ duration). Early medieval Europe was largely indifferent to transportation, and even indifferent to a degree to cities. Roads were poor, and virtually impassable in the rainy seasons, spring and fall. What modes of transit there were consisted of walking, horseback riding, oxcart, and shipping. There were no great port cities in western Europe during this period of time, so even shipping traffic was minimal.

Life in early medieval Europe was intensely local. There were rare travelers (merchants, soldiers, itinerant musicians and preachers, etc.), but most individuals never traveled beyond a few miles from the village where they were born. Life was focused on the rural manorial estate, which was a self-contained and self-sufficient community in which all needs were met (if they could be met) locally, and the local feudal lord was a law unto himself. This was an economic (and cultural) system born of risk aversion and the inherent food security of subsistence agriculture.

Trade was minimal, usually a mere trickle of luxury goods, which dovetailed with the social structure of the society: only the feudal lords had disposable income and so were the sole consumers of imported luxuries, which were employed to enhance the image and status of the local court. The institutionalized restrictions on social mobility embodied in the feudal system (or even the mere appearance of social mobility, which was controlled by sumptuary laws), mirrored the absence of geographical mobility: there was a place for everything, and everything was expected to remain in its place.

The lack of transportation and communication networks meant that idea diffusion was slow. Risk averse subsistence agricultural communities were conservative in the extreme when it came to the adoption of new technologies, not to mention the adoption of new ideas. Because food production was local, a failed local agricultural experiment resulted in starvation. Better to stick to old, known ways of farming than to risk a famine; life was hard enough without courting disaster.

A civilization of this kind, then, is possible, i.e., a civilization economically indifferent to transportation, but it is a civilization that is self-limiting, not only in transportation choices, but also self-limiting culturally, intellectually, socially, and economically. This is transparently obvious from the role that transportation and communication networks play in idea diffusion. Moreover, a regional civilization that remained economically indifferent to transportation would remain a regional civilization and would not grow to become a planetary civilization. Civilizations that build planetary scale transportation networks will eventually encircle exclusively regional civilizations, which latter will become assimilated to the former, which surround and absorb them.

However, it is possible to imagine a civilization in which the economy is so large that the buildout of a spacefaring capability for scientific research represents a marginal economic activity so that the economic infrastructure of that civilization could remain largely indifferent to its spacefaring capacity. This would be implicitly a conception of civilization in which some non-spacefaring economic infrastructure played a large role, or, at the opposite end of the spectrum, a civilization that voluntarily divests itself of its large-scale industrial infrastructure and retains only what is minimally necessary in order to maintain a spacefaring capability for scientific purposes. If a civilization achieved a sufficiently high level of technology, it might live with a light footprint on its homeworld and not require great industrial resources for spacefaring. However, this level of technological achievement would likely only come about as the result of an earlier industrial capacity build out as a necessary stage of development, which was then later dismantled.

Intellectually Indifferent Spacefaring Civilizations

A civilization might be intellectually indifferent to spacefaring even while incorporating spacefaring as an integral part of its economic superstructure. Space could be used for transportation, for economic development, for population expansion, even for entertainment, adventure, and excitement, and still be intellectually irrelevant if that civilization does not exploit its spacefaring capacity for intellectual stimulation, i.e., for scientific, philosophical, and aesthetic growth and the further development of its conceptual framework.

Here we have several historical analogies that we can invoke. It is at least arguable that seafaring was at the heart Viking civilization and Venetian civilization, and was no less central to Iberian civilization during the Age of Discovery, when both Spain and Portugal explored at a planetary scale. By contrast, Mediterranean seafaring was extremely important to Roman and later Ottoman trade, but one would not say that Roman civilization or Ottoman civilization had seafaring as a central project. Our own civilization today is a case in point in this respect: since the invention of the shipping container, international seafaring trade has been central to the global economy, but I don’t think many would be willing to identify seafaring as the central project of contemporary planetary civilization.

The International Chamber of Shipping notes, “The worldwide population of seafarers serving on internationally trading merchant ships is estimated at 1,647,500 seafarers, of which 774,000 are officers and 873,500 are ratings.” In other words, all the seafarers in the world today represent too small of a population to appear in any planetary employment statistics. Even if we were to add port, longshore and warehouse employees we would still not be up to one percent of global population. This is less than the portion of global population presently employed in the agricultural industries of industrialized societies. If we expand the scope to include all workers in the global transportation industry—shipping, air freight, rail, and trucking—this would probably be a respectable figure, but even this respectable figure would not represent a powerful force shaping contemporary society.

Employment numbers, however, do not tell the whole story. The software industry today is far more powerful than transportation (or, for that matter, agriculture) in terms of setting the political and social agenda, despite the fact that employment in the software industry is not large on a global scale. In a 2014 study, The Economist Intelligence Unit estimated direct global employment in the software industry at 2.5 million, with a total of 9.8 million employment if indirect measures are included. This is probably significantly less than global employment in the transportation sector, but, at the present juncture of history, it is far more influential.

Transportation sector employment and influence is almost invisible; software industry employment and influence is highly visible, frequently the focus of political conflict, and influences a mass audience through ubiquitous personal electronic devices. We hear about transportation when an airplane crashes or a train wreck occurs; otherwise, it is part of the economic infrastructure that we take for granted, much as we take it for granted in the industrial world that, when we turn on a light switch, the light will come on because the electrical grid is functioning.

Spacefaring conceived after the manner of the transportation sector of an interplanetary or interstellar economy largely conceptually indifferent to spacefaring, in no way ensures that spacefaring as an end it itself will play any constitutive role in the central project of a civilization with a spacefaring capacity.

Morally Indifferent Spacefaring Civilizations

Indifference to transportation (i.e., spacefaring in a spacefaring civilization) need not be only an economic or conceptual indifference. A civilization might be morally indifferent to spacefaring even while incorporating spacefaring as an integral part of its economic institutions and conceptual framework, and we can express this as a spacefaring civilization in which spacefaring is not the central project of that civilization, nor is it closely integrated with the central project.

An example of civilization morally indifferent to spacefaring is one of the most familiar conceptions of the potential future state of civilization. Indeed, indifference to spacefaring dovetails with what I have called the SETI paradigm (i.e., that technologically advanced civilizations will communicate rather than travel over interstellar distances), as a robust spacefaring engagement would be expected to drive forward spacefaring technology so that it would be unrealistic to postulate a civilization that focused on spacefaring for hundreds or thousands of years and yet still remained incapable of interstellar travel, which is a central tenet of the SETI paradigm. [5]

Dyson’s one-page paper “Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation” [6] was published in 1960 and Kardashev’s paper “Transmission of Information by Extraterrestrial Civilizations” [7] was published in 1964. The two papers have become entwined in collective memory, largely because Dyson’s Dyson sphere provides a perfect model for Kardashev’s Type II civilization; it is almost as though the authors had coordinated their efforts and were jointly involved in the exposition of one and the same cosmological extrapolation of civilization. This is a vision of a possible future state of civilization that is expansive to the point of grandiosity, but it is not a vision in which spacefaring plays a role as a central project.

Dyson’s conception of a civilization so advanced that it could build a Dyson sphere, but so uninterested in other civilizations that the only way it could be detected would be by its distinctive IR signature, contrasts sharply with Kardashev’s conception of a civilization radiating information to the universe as powerfully as a quasar, but both were approaching the idea of cosmologically significant civilizations [8] from the perspective of SETI, i.e., from the perspective of the technosignatures of a very old and very advanced civilization, which might, with luck and skill, be detected by younger and less advanced civilizations.

Dyson focused on thermodynamically inevitable waste heat that even a civilization indifferent to the wider cosmos must leave as a technosignature, while Kardashev focused on civilizations so demonstrative to the wider cosmos that they would radiate as brightly as a quasar; these are antithetical orientations toward a civilization’s relationship to its cosmological complement (i.e., everything outside itself), but neither Dyson nor Kardashev had much to say about spacefaring in this context.

In Dyson’s later paper, “The Search for Extraterrestrial Technology” [9] he discusses the disassembly of planets in order to build megastructures, which would require robust spacefaring technologies, at least within a civilization’s home system, but this discussion is almost entirely utilitarian and instrumental. In other words, disassembling entire planets in order to build megastructures as Dyson describes in this paper is a matter of the economic infrastructure of a civilization seeking to maximize its Lebensraum within its home system.

Dyson wrote another paper, “Interstellar Transport,” [10] which is much more focused on actual spacefaring, but, again, the emphasis is upon spacefaring as a transportation solution to economic problems posed by spacefaring civilization; there is no discussion of spacefaring as an end in itself. The final paragraph of this paper gives more of the context within which Dyson was developing his thoughts on interstellar transport, though Dyson prefaces these reflections with the assertion, “I am only concerned with the engineering aspects of the enterprise.” While there has been little discussion of Dyson’s social vision of a spacefaring future, there has been a great deal of discussion about Dyson spheres, [11] as well as the engineering problems of megastructures that would face any Kardashevian supercivilization. I will not here attempt to address Dyson’s conception of the social consequences of spacefaring, which he does address in several articles [12]; I only wish to note in this context that spacefaring is a necessary condition of megastructure construction, but not necessarily the focus of a civilization engaged in megastructure construction.

Kardashev is similarly spare in his discussion of actual spacefaring. In his 1964 paper he mentions only, “…we may anticipate that space rockets will clear up the question of whether or not life exists on other planets in the solar system in the years to come.” [13] This is entirely of a piece with Dyson’s exposition, though Dyson’s civilizations are indifferent even to communication with the outside world, whereas Kardashev’s civilizations are engaged in a central project of transmitting a cosmological legacy to the universe at large.

What would civilizations of this scope and scale, nevertheless morally indifferent to spacefaring, do with the time and resources available to them? This is a question that I have explored several times, for example in Stagnant Supercivilizations and Another Formulation of Stagnant Supercivilizations and What Do Stagnant Supercivilizations Do During Their Million Year Lifespans? and Supercivilizations and their Cosmological-Scale Dark Ages, inter alia. The question could be turned around, and we could ask instead, What would a supercivilization not do, given the resources available to it? Our parochial imagination, acculturated during the early stages of the development of civilization, limits our ability to answer this question.

As futurism scenarios today increasingly focus on the technologies that have experienced exponential growth over the past few decades, an obvious response to a question like this would be an answer that emphasized computers, robotics, and artificial intelligence. Michael Lampton has called a scenario like this the possibility of an “information-driven society,” asserting that the development of, “…increasingly powerful tools for observation, modelling and data processing,” may drive social change resulting in a re-direction of development: “On the multimegayear time scale of species evolution or interstellar travel, this change is rapid enough to be regarded as a step-function transition to an information-driven society.” [14]

For Lampton, a human information-driven society would still be interested in the wider universe, but this is not necessarily the end point of this developmental trajectory. Rather than turning outward, and employing spacefaring technologies to project itself into the cosmos, an advanced civilization may turn inward and explore a virtual cosmos. John Smart has called a later development of this trend the Transcension Hypothesis, in which, “…a universal process of evolutionary development guides all sufficiently advanced civilizations into what may be called ‘inner space,’ a computationally optimal domain of increasingly dense, productive, miniaturized, and efficient scales of space, time, energy, and matter, and eventually, to a black-hole-like destination.”

We could construct a developmental trajectory encompassing Lampton, Dyson, and Smart in this way: the development of computational technologies converges upon an information-driven society, still oriented toward the outside world, but increasingly focused on information acquisition and processing. To optimize this development, solar insolation harvesting increases until the harvesting of the sun’s energy converges upon a Dyson sphere, supporting a computational infrastructure by means of a spacefaring technology optimized to produce platforms for the harvesting of solar insolation, rather than for space travel and exploration for its own sake. During the period of convergence upon Dysonian totality, the motivational structure of the civilization shifts away from information acquisition and processing that involves the universe beyond (perhaps exhausted by this time), turning inward to virtual worlds and thus the new focus of civilizational optimization converges on a scenario like that of Smart’s transcension hypothesis.

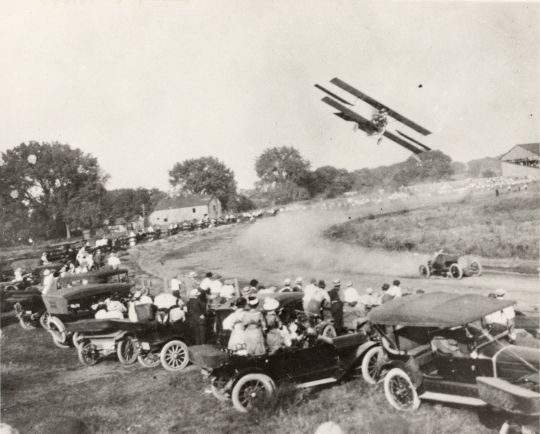

Image: Curtiss “Beachey Special,” piloted by Lincoln Beachey, in banking flight over mile racing track, Davenport, Iowa, September 1914 (https://airandspace.si.edu/collection-objects/beachey-lincoln-oldfield-berna-eli-barney-exhibition-flight-barnstorming).

The Barnstorming Era in Spaceflight

Over the longue durée, spacefaring might pass into and out of the central project of an advanced technological civilization that had the power to act upon spacefaring initiatives if it chose to do so, but this was not always or continuously the social consensus. One could easily imagine a civilization coming into advanced spacefaring technologies, and there being a period of great excitement during a phase of expansion, only to be followed by indifference once spacefaring became routine.

It is to be expected that in the early stages of spacefaring there will be a “barnstorming” era, in which spacefaring will be a challenge and a sport, and, at the farthest reaches of technological capabilities of spacefaring, it will remain a dangerous (and therefore thrilling) sport for some time to come. We are almost a hundred years’ past the barnstorming era for atmospheric flight, and still today there are wealthy sportsmen who indulge themselves by setting new records. The potential scope for spacefaring is far more extensive than that of flight (both in terms of technology and in terms of the spatial extent opened up to sporting opportunity), so that spacefaring as sport, as adventure, and as a romantic engagement with the world, could endure for hundreds if not thousands of years. Nevertheless, this sort of spacefaring is likely to be demographically marginal, of interest primarily to enthusiasts, and largely invisible to the general public.

Say, then, that the barnstorming era in spacefaring endures for a thousand years, after which time a technologically advanced civilization in possession of spacefaring technologies settles into a routine in which spacefaring is a pedestrian activity incorporated into the economic infrastructure of this civilization. After a period of lethargy and apathy, perhaps even a prolonged period of stagnation in which little or nothing is done to improve spacefaring technologies (which period could endure for thousands of years), a civilization might rouse itself once again and project itself outward into the cosmos, with renewed vigor and to a greater extent.

Because the scale of time at which civilization as we know it develops is so short in comparison to the scale of time of cosmology, a cosmologically significant civilization might pass through several multi-thousand year cycles of spacefaring as a central project of a civilization, followed by multi-thousand year periods of civilization in which spacefaring plays no role whatsoever in the central project of the civilization in question.

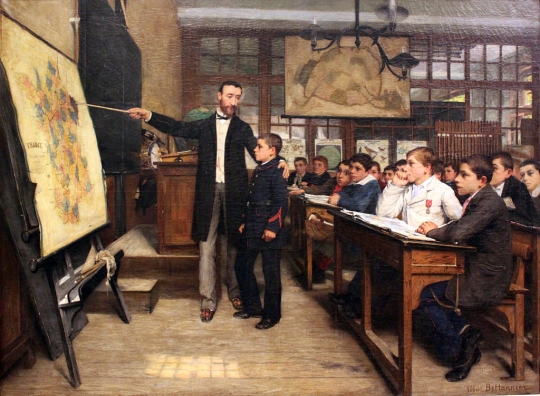

Image: La tache noire (“The Black Stain”), by Albert Bettannier, in which Alsace-Lorraine is depicted as a black spot on the map of France.

Central Projects, Selective Indifference, and the Development of Civilizations

In the above, spacefaring has served as a lens through which we can view the structure of civilization. What has been investigated here in terms of spacefaring could be applied to other technological capabilities or sociopolitical institutions, present or potential. For example, a similar study could be made of transhumanism, or, rather, in proper generality (i.e., in a non-anthropocentric formulation), the technological augmentation of an intelligent biological progenitor (or progenitors) of civilization. A civilization might take non-anthropocentrically defined transhumanism (perhaps trans-speciesism) as the central project of its civilization, or transhumanism could be economically, conceptually, or morally indifferent even if the technology for these developments is available, as follows:

- Properly trans-biological civilization: conceptual, economic, and moral trans-speciesism

- Indifferently trans-biological civilization: conceptual indifference to trans-speciesism

- Indifferently trans-biological civilization: economic indifference to trans-speciesism

- Indifferently trans-biological civilization: moral indifference to trans-speciecism

Each of these permutations could be given an exposition as I have given above in relationship to spacefaring. Perhaps just as importantly, indifference is a matter of degree, so that a survey of many different civilizations would be likely to result in examples of indifference from the mild to the total, and indifference itself is a mid-point between enthusiastic embrace on the one hand and aversion and avoidance on the other.

We would do well to distinguish between total indifference, in which an idea or activity simply plays no part whatsoever in the lives of a given population, and active aversion, in which an idea or activity is pervasively present through its avoidance. [15] Superficially these conditions look similar, and the two may be conflated in a low resolution survey of a field, but each points to a fundamental and distinctive difference in the structure of human motivation that will be manifest in other ways in other aspects of life.

This kind of motivational phenomenon is crucial for understanding the central project of a civilization. If we mistake aversion for indifference, we may suppose that some topic might be innocently broached, only to find that we have committed the worst possible faux pas. If we mistake indifference for aversion, we may fail to introduce some crucial but thoughtlessly elided matter, thereby dooming an otherwise hopeful enterprise. In either case, we will fail to understand what is transpiring before our eyes even as we believe ourselves to grasp the essence of the situation, and this is a recipe for disaster.

All central projects incorporate matters of both indifference and aversion alongside matters of engagement and propagation. In order to understand what is going on in a civilization at the largest scale of its development, we must mind these distinctions carefully, as the past leading up to the present structures we observe, and the future developments that will follow from these present structures, would be different in the cases of different motivational structures (and the evolution of these motivational structures). History, then, manifests the development of an idea in time. If we identify the wrong idea as being central to a civilization, or if we fail to appreciate, for example, the difference between indifference and aversion, we will fail to understand the nature of the civilization in question.

For example, how and why did the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand expand to engulf the world in a war of planetary scale, rather than resulting in just another Balkan war (such as were fought, without the planetary scale of loss of life or property, in 1912 and 1913)? Europe before the First World War was a continent riddled with silences and unspoken animosities, given concrete expression in secret treaties and alliances, and, at the same time, the great powers of Europe were engaged in enterprises throughout the world. Balance of power politics after the example of Bismarck had not only constructed a system of alliances, but also a system of aversions no less carefully cultivated, but shrouded in obscurity. If we consider the motivational structure of Europe in 1914 as the central project of European civilization understood only in terms of publicly avowed engagements, without reference to the underlying indifference, aversions, and animosities, we would be as surprised as anyone at the time at the outbreak of a planetary-scale war.

Limitations of Historical Analogies

Since its inception in the latter half of the twentieth century, what has been the role of spacefaring in the central project of civilization? One could argue that the Cold War Space Race was primarily an ideological undertaking, so that space travel during the Space Race was part of the intellectual superstructure at that stage in the development of our civilization, and that it did not inform the central project of civilization at that time. One could also argue, alternatively, that the Cold War Space Race was a temporary manifestation of the central project of planetary civilization at the time, serving to align the interests of individuals and political entities globally, as a prelude to a later, more robust central project of planetary civilization (yet to come).

Why did the Cold War not spill over into a planetary-scale war, as with the escalation that preceded the First World War, or why did the Cold War not become the first war in space? It would be folly to assign a single cause to any course of events as complex as those of the twentieth century; many forces were in play, not least the palpable fear that a war would result in a nuclear exchange that would have meant the end of human civilization. But the Cold War Space Race itself fizzled after the moon landing (perceived as the US winning the Space Race). Other possibilities might have played out under other conditions. If the Space Race had become the primary outlet of superpower competition, the Space Age might have developed differently, perhaps along the lines of Spanish/Portuguese rivalry during the Age of Discovery, without having to sacrifice Earth to a thermonuclear exchange. [16] But that didn’t happen either; instead, the Space Age moved from initial enthusiasm to widespread indifference.

It could be argued that too great a reliance upon historical analogies is a weakness in attempting to understand the nature and structure of future civilization, but in this present context I find the analogies explored here to be quite telling. While individuals like myself still find spaceflight to be as exciting as when it was new, for many the excitement now has a tinge of nostalgia for the Space Race. Even I find space boring when I hear people banging on about the size of the global satellite industry; this is where the money is, but this is a pedestrian aspect of spaceflight with none of the adventure and none of the excitement. This is space according to the economic infrastructure, and shorn of its significance for the intellectual superstructure and the central project of a civilization.

However, I recognize that my own attitude probably represents a small minority, and to cast the future in the light of the interest of a small minority is almost certainly to get it wrong. What the above analogies make clear to us is that, if I have misrepresented the spacefaring future, it is because I have gotten the emphasis wrong, and not that the future will be without a spacefaring component. A fully spacefaring future for humanity might have spacefaring as simply the transportation infrastructure of a large and thriving civilization, with little or no importance for the central project of this civilization, and therefore only a marginal concern — Do the spacecraft run on time?—for the majority of individuals who are (or would be) a part of this civilization.

Notes

[1] For those who see spacefaring as the future of our civilization, the cultural and social impacts of spacefaring are ultimately much more important than the economic or technological impacts; for those signing the checks for the next satellite launch, the economic and technological side of spacefaring will always be the most prominent factor. However, in what follows I will be discussing civilizations with a mature spacefaring capability, which would make the relationships between individuals embedded in different sectors of society different from the way we regard spacefaring today in terms of its potential.

[2] For more on this model of civilization cf. “Martian Civilization” (note 2 and its context) and my talk “The Place of Lunar Civilization in Interstellar Buildout.” I discussed my use of “intellectual superstructure” and “economic infrastructure” (terms I have adopted from Marx, though other terms will work equally well) in my earlier talk, “What kind of civilizations build starships?” but I hadn’t yet at that time integrated the idea of a central project into this model.

[3] For example, a civilization that chose to remain tightly-coupled to its homeworld but nevertheless continued to maintain an active interest in scientific questions that could only be studied through spacefaring, might build scientific instruments dependent upon spacefaring, though this capacity would likely be marginal in comparison to the total size of the economy. A civilization like this would be a scaled up version of contemporary terrestrial civilization, which is not at present settling other worlds within our solar system, but which has studied the other worlds of our solar system though robotic spacecraft.

[4] Throughout this essay I am using “economic” in its widest possible significance, in the sense in which Alfred Marshall wrote of economics as, “…a study of mankind in the ordinary business of life; it examines that part of individual and social action which is most closely connected with the attainment and with the use of the material requisites of wellbeing.” (Principles of Economics, Book I, Chapter I, Introduction. § 1)

[5] I give an exposition of the SETI paradigm in “Stagnant Supercivilizations and Interstellar Travel.”

[6] Freeman Dyson, “Search for artificial stellar sources of infrared radiation,” Science, 131(1341):1667-1668, 1960.

[7] N. S. Kardashev, “Transmission of Information by Extraterrestrial Civilizations,” Soviet Astronomy, Vol. 8, No. 2, Sept.-Oct. 1964, 217-221.

[8] What is a “cosmologically significant civilization” and how does it differ from a cosmologically insignificant civilization? I cannot answer this question now, but it is a problem on which I am working. I am counting on the reader’s sympathetic intuitive reading of the term, and if it should prove, upon investigation, to be overly problematic, it can be dispensed with in this formulation without loss. A minimal way to define a “cosmologically significant civilization” would be as a civilization that produces a technosignature that can be detected over interstellar distances. A higher threshold would be the production of technosignatures visible over inter-galactic distances. A different approach might be in terms of scale (like the Kardashev typology) or in terms of age.

[9] This paper is included in Selected Papers of Freeman Dyson with Commentary, with a Foreword by Elliot H. Lieb, Providence and Cambridge: American Mathematical Society, 1996, pp. 557-570 (though the original journal pagination of 641-654 is also retained in this edition). With the exception of Dyson’s original Dyson sphere paper, “Search for Artificial Stellar Sources of Infrared Radiation,” the other papers by Dyson cited in this essay are not included among these Selected Papers.

[10] Physics Today, Volume 21, Issue 10, October 1968, doi 10.1063/1.3034534

[11] Papers on Dyson spheres appear regularly. For example, at least two new Dyson sphere papers appeared on Arxiv in April 2018, “On the possibility of the Dyson spheres observable beyond the infrared spectrum,” by Z. Osmanov and V. I. Berezhiani (Submitted on 11 Apr 2018), and “SETI with Gaia: The observational signatures of nearly complete Dyson spheres” by Erik Zackrisson, Andreas J. Korn, Ansgar Wehrhahn, and Johannes Reiter (Submitted on 23 Apr 2018).

[12] For example, “Human Consequences of the Exploration of Space” in Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Sept. 1969, Vol. XXV, No. 7, pp. 8-13, and “Pilgrim Fathers, Mormon Pioneers, and Space Colonists: An Economic Comparison,” in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Vol. 122, No. 2 (Apr. 24, 1978), pp. 63-68.

[13] Kardashev, ibid., p. 221.

[14] Michael Lampton, “Information-driven societies and Fermi’s paradox,” International Journal of Astrobiology 12 (4): 312-313 (2013).

[15] For a concrete example of being pervasively present through avoidance, after the Franco-Prussian War, when the Germans annexed Alsace-Lorraine (which they called Reichsland Elsaß-Lothringen), of this territorial loss it was said in France, “Think of it always; speak of it never.”

[16] An extended Cold War Space Race has been imagined in the counterfactual history of Mac Rebisz’s Space That Never Was, who writes of his artistic vision, “Imagine a world where Space Race has not ended. Where space agencies were funded a lot better than military. Where private space companies emerged and accelerated development of space industry. Where people never stopped dreaming big and aiming high.”

Like most people who write about these topics, you don’t distinguish between collective indifference and individual indifference. That distinction matters especially to your SETI discussion.

As you said, in our era of collective indifference to seafaring, our still has millions of individual seafarers, motivated by various species-atypical priorities. Likewise, collectively spacefaring-indifferent societies should be expected to still have millions of weirdos who are for some reason really into the idea exploring space, claiming habitable territory, and expanding their civilization. It’s not like the complete indifference of their peers stops this from happening.

Models in which indifference explains how an alien society might be technologically advanced and yet non-expanding are incoherent. Our society is indifferent to stamp collecting, but that doesn’t stop me from doing it. If somehow it did, indifference could not explain it. We would have to *care very deeply* about stamp collecting in order to actually keep it from happening – more deeply than we care about almost anything else. (We care deeply about preventing illegal drugs from killing vulnerable people, yet it happens every day.) A technologically advanced society indifferent to spacefaring will radiate out millions of spacefaring individuals who are just into that kind of thing.

The relevance of these thoughts to SETI discussions should be obvious, but it’s also relevant to our own plight, as we live in a spacefaring-indifferent world. We might soon find ourselves in a world where the spacefaring capacity of weirdos like Bezos, Musk and Branson eclipses the capacity of collectively funded organizations. But my argument is that weirdos are all that an indifferent society needs in order to expand into space. It’s not optimal, but neither is it a dealbreaker.

I agree that it is important to distinguish between collective indifference and individual indifference. While I’m thinking about it, I will also note that it is important to distinguish between conscious indifference (knowing that one is indifferent) and unconscious indifference (not knowing that one is indifferent). The above essay may be read with the assumption that I am, throughout, addressing collective indifference, because I am addressing civilizations on the whole, and not individuals or groups that jointly constitute a civilization. A more detailed exposition would bring out the difference between individual and collective indifference. I partly addressed this in my talk in Monterey last year (“The Place of Lunar Civilization in Interstellar Buildout”), in which I noted that in mature, complex civilizations there are many individuals that are more-or-less entirely disconnected from the central project of the civilization of which they are a part, thus being morally indifferent (individually) to that civilization.

I completely agree with your assertion that, “Models in which indifference explains how an alien society might be technologically advanced and yet non-expanding are incoherent.” This is the rock on which a great many proposed solutions to the Fermi paradox come to grief. I am not suggesting that civilizational-scale (collective) indifference to spacefaring will ultimately render us an exclusively planet-bound civilization. The outliers who are, as individuals or as groups, interested in spacefaring, may constitute a sufficiently large and well funded group to make humanity a spacefaring species. And if this fragment of humanity grows in numbers beyond the numbers of individuals who can be supported by a single planet, the outliners will, in the long run, represent the greater fraction of the species.

Best wishes,

Nick

Neilsen does describe civilizations were only a small subset of the population is space faring, but doesn’t call them weirdos. If we look at our own history of exploration, outcasts, misfits, and adventurers do feature prominently and an industrial scientific civilization will empower those misfits and outcasts. I have no problem believing that a future human, on their own, will be able to settle a star system and convert it into a super structure.

In the context of SETI/METI, I think we should be cautious not to exaggerate the impact of an indefinitely parsable population of individual and civilization personalities. Imo, as the population becomes more varied, the likelihood that any one personality dominates diminishes and the likelihood that nuanced, “just so” neighborhoods exist increases.

The analogies you use aren’t necessarily accurate. You use analogies that depend on access to abundance, stamp collecting, drug use, etc. If the development of industrial scientific civilization is rare, then humanity would be analogous to the crown jewels of England or the Hope diamond. We may be something the galaxy hasn’t seen for 100s of millions of years, a stumbling toddler civilization of delicate weirdos. For an ancient peoples we would be a monstrously difficult resource or relationship to cultivate.

Biology has the imperatives of survival and accreting biomass through growth and replication. This implies the acquisition and expenditure of energy.

Civilization is a way to more efficiently utilize matter and energy towards this end. Once non-biological and post-biolocical extensions emerge from the biological control of their origins, they may not share in our imperatives.

Space, celestial bodies and beings, and life amongst them have been part of important mythological narratives in most human traditions going back into the dim mists of antiquity. There has never been the lack of a “spacefaring” attitude.

The earth’s gravity well has kept humans from space until the refinement of rocket technology made exiting it possible, though still far from convenient. Should technology advance to the point where it becomes convenient, the extent of its adoption will depend on the degree of its convenience. Such convenience will have to include a solution to the problem of radiation beyond the van Allen belts.

A Kardashev 2 or beyond civilization may have a profusion of available energy; this could allow different cohorts of humans to choose different lines of development, which given enough time might evolve into lineages as different as different breeds of dogs, cats, horses or cattle.

The possible disruption of the Solar System in the merger with Andromeda, and the red giant transformation of Sol would both act through the survival imperative on any biological civilizations extant at that time to seek ways out of such impasses.

Even if non-biological and post-biological extensions of terrestrial life (or, for that matter, post-biological extensions to any life found anywhere) do not share our imperatives, they will still be subject to selection. For post-biological entities to effectively propagate themselves in our large and diverse universe, they would need to acquire energy and material resources and expand by adaptively radiating, modifying themselves to best take advantage of local cosmological conditions.

This quasi-biological behavior in response to cosmological selection would shape the psychology of any post-biological entity attempting to find a niche for itself in the cosmos. The evolved psychology of such an entity would not be arbitrary, but would respond to its environment. While we can speculate on fantastically diverse minds unrecognizably different from human minds, and the inscrutable imperatives such minds might entertain, I suspect that there will only be a few viable forms that minds can take that are consistent with their ongoing survival. Whether human minds will eventually prove to be such a mind, i.e., a mind that can assure its ongoing survival at a cosmological scale, remains to be seen.

This article raises a question: *Is* there such a thing as a Central Project to any civilization? While rulers and leaders often–if not always–think in such terms, most people do not, except in times when their way of life is threatened (such as during wartime). Also:

The overview effect is, despite its emotional impact, illusory. All problems and differences seem unimportant or less important when viewed (or mentally perceived) from a distance. When they return to Earth, space travelers find themselves again immersed in all of the problems and challenges of everyday life–car payments, their kids’ braces, fixing the house or hiring contractors to do so, etc. (I recall reading an article by one of the American ISS crew members–I forget who it was–whose wife reminded him of the family’s Earthbound challenges after he told her about the wonders of flying through the Northern Lights.)

I find it interesting that you say the overview effect is illusory despite its emotional impact. But if the overview effect has an emotional impact, ipso facto it is not illusory. I think the important thing here is to recognize the the overview effect is not one, but many. It influences some individuals in one way, other individuals in another way, and some individuals not at all. No doubt some space travelers, immediately immersed in bills upon their return, retain little of the overview effect over the longue durée; others will act upon it as a credo.

About central projects and civilizations, this is a much longer topic that I will have to go into at length at another time. I don’t claim my model of civilization, which includes the notion of a central project, to be complete or correct. The important thing to me is simply to have a model that provides a framework for discussion. To date, we haven’t had that in the study of civilization. I would be very happy if the study of my model led to insights that required revisions to the model or a complete transcendence of the model for a different model. That is the nature of intellectual progress.

What I have in mind as a central project has little or nothing to do with what leaders or rulers have in mind. Central projects almost always arise organically from the life of a people; leaders may manifest a central project–as did the Egyptian Pharaohs–but they do not create it, nor can they arbitrarily alter, eliminate, or replace a central project.

Best wishes,

Nick

An illusion is something that isn’t real, but is incorrectly perceived as being real. The overview effect is an illusion (like those of children who are afraid of monsters hiding under their beds) because it ^seems^ to be real at the time (just as a mirage or a very vivid dream may look or feel real), but in the end, it isn’t. When the physical (and/or psychological) distance is removed, the importance and relevance of the Earthbound circumstances and problems–which were there all the time–are simply noticed again, and:

I don’t doubt the emotions that the astronauts feel. But as with the imagined monsters under the beds (which the children certainly feel afraid of), the notion that being temporarily removed to a perch high above the Earth makes Earthly problems petty and small simply isn’t real. (If [eventually] independent, self-sustaining space colonies–or such colonies on the Moon, Mercury, or Mars–are developed, it *will* be real, because a space settler, Lunarian, Hermian, or Martian could say–and mean it–“Earth isn’t my home, and the Terrans’ problems aren’t my concern.”)

If it was real, the thoughts that the emotions evoke would make sense and would be applicable everywhere (including on Earth), but they don’t and aren’t. It isn’t like, say, the discovery of radio waves, which we were unaware of until suitable detectors were developed. No one had ever seen them before (just as no one had ever seen the Earth from afar until the Space Age), but the difference is that such invisible radiations exist whether or not we’re using those detectors to register their existence.

The “Break-Off Effect,” which began to afflict high-altitude jet pilots and stratospheric balloon pilots–particularly those flying in monotonous circumstances of isolation–in the 1950s, was a deadly illusion (Major David G. Simons, a USAF physician, documented its effects on him during the Man-High II balloon flight in 1957). The radio voices of personnel on the ground seemed unimportant, and the aviators felt separated from the Earth and just wanted to fly on and on. Part of the reason for the worldwide manned spacecraft tracking network (in addition to keeping tabs on the crews’ physical health and the spacecraft’s condition) was to prevent the isolation and monotony that could lead to the Break-Off Effect in astronauts.

Regarding Central Projects, I think you’re right about them being organic. Unlike a conspiracy, which goes against the surrounding society in some way, and requires conscious planning (as in the Lincoln assassination conspiracy among Booth and his co-conspirators, to give one example), the Central Project of a nation or society requires no planning (or at most, very little, which is done to help the nation, as with Washington, Jefferson, and their fellow patriots). A Central Project isn’t a conspiracy, but “a population of people, ‘walking in the same direction’ with a united purpose and vision.” They may not be moving in lock-step (and usually aren’t), but they support and contribute effort to the Central Project because they see it as being a way to bring their own desires to fruition.

The problem with non-centralized consensus is that it can change unpredictably, like the direction of flight of bird flocks. Ensuring the direction is consistent requires some centralized control, such as monarchies or authoritarian government. I find it hard to reconcile the political flipping of political party control of the government in most western democracies with your characterization. Add the apparent conflict between Enlightenment thinking and religious fundamentalism that has wracked Turkey and the Middle East, and appears to be showing strong signs in the US, and there may be some dispute about The Enlightenment as a central project of western civilization.

What is happening now (in the U.S. and elsewhere–China has experienced it repeatedly over the millennia) is nothing new, as history shows; it’s just something that hasn’t occurred–in the U.S., at least–within living memory. What is happening now is tame compared with the polarization and rancor that occurred in the U.S. at various times in the past. It’s the vigor of any living organism, which has its times of quiescence and its times of great activity.

Akhenaten is a prime example of this. He tried to significantly alter the central project of Ancient Egypt, but in the end was defeated by social inertia and the entrenched priesthood.

I agree. I think that ultimately most determining are the natural circumstances in the widest sense, and the opportunities and limitations that they offer. I think of Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs ans Steel. Why and how civilizations arise where and when they arise. This may not be a popular idea in our culture with the illusion of (central, planned) control. But it is closest to the concept of selective advantage and long-term survival: there are given niches out there and those who will occupy them are those who are in the (technologically and economically) best positions to utilize them.

And people’s motivations are driven by the presence of such niches and their possibilities to utilize them. So, I see it as a combination of the factors of nature, technology, economics and what the author calls ‘concept’, which is people’s ideas,knowledge and (personal) motivations. I think central governance and planning plays only a minor and temporary role in all this.

Example idea: if Mars had been a lush Earthlike planet, we would have been there already, having several colonies there. The motivation to go there would have been tremendous and unstoppable. For any government.

Perhaps the grand central project of civilization is always to expand the experience of consciousness, to live more. I can’t think of anything that emerges from the STEM recursive cycle that does not forward that central project. We should not be surprised to find ETIs not only with bigger libraries and toys but bigger consciousnesses.

Space habitats devoted to industries may be a key to expansion, removing much pollution from Earth, maybe largely run by robots.

Others may be living spaces for people and of course plants and animals. People will be able to organize their own societies there, an incentive to move from the home world; that certainly played a part in European colonization 1500 to 1800.

What’s important is that they generate wealth that will benefit people on the home world. That will be what leads to further growth.

Our world may be perfectly suited to this since it isn’t so big its gravity will keep us down, it has a satellite we know we can reach, and needs more resources if we’re to become even more advanced.

Other civilizations may be quite rare and many may be limited to their world by their biology, but that doesn’t apply to us.

We are already a space faring civilization. I don’t think we will ever give up on the goal of interstellar travel. We will have it to leave this planet in 300 million years when the global climate will become too hot for life to survive since the Sun’s brightness increases 10 percent every billion years. The Sun will move of it’s main sequence hydrogen burning in five million years and become a red giant.

We will always be a space faring civilization. We will be an interstellar civilization in the future. It’s obvious that time and technology are a factor since the more advanced the technology, the easier interstellar travel becomes. The intellectual indifference and economic indifference will never take complete control. Modern Man, culture and society and the future of humanity are symbolized by space travel and technology and these were initiated in the collective imagination with the first balloon flight. They may have even began when we first dreamed of flight.

I do not disagree that eventually whoever is still around on Earth – assuming our planet as we know it is still in existence – when Sol starts to expand into a red giant will have to do something about extending our star in its yellow dwarf state, or more further out into the Sol system, or leave the system altogether.

What I do doubt is that whoever is on Earth in 300 million year time will be human in any form like us. Think how much our species has changed in its seven million years on this planet, along with the fact that of the fifteen known species of hominids in all that time, only one is left.

Look at how rapidly we have changed and grown and affected our world: Ten thousand years ago there were no real civilizations yet. Human population numbers did not reach one billion until 1800 and now we are at 7.6 billion and rising. So just imagine how different things may be in only the next few centuries, especially with genetic engineering and computer technology.

Something that might be of some relevance is this thread from Michael P. Oman-Reagan on Twitter, which makes some interesting points about SETI assumptions and the framework in which these topics are discussed. Food for thought.

Is there any law stopping any of us from invading remote tribes using guns and bombs? Of course there is no bail-out after the s*** hits the fan for sure. Playing king or “God” in such places isn’t that much interesting anyway but those who enjoy playing game of territories might disagree.

Oh well, we only have one example so far hence almost everything is “educated” speculation.

Well, for one thing, the modern world is really short on remote tribes to invade.

There are those remote indigenous tribes in South America which are in danger from encroaching civilizations because they sit in valuable rain forest land.

I agree with Dr. Wentworth. I’ve noticed that many parents (mostly white, mostly affluent) see space as something for the kids. Star parties, field trips to observatories, vacation stops at NASA facilities – they are all considered vaguely “educational.” If parents were not parents, most would not visit these places. Parents do not normally expect their kids to become astronauts, scientists, or engineers as a result of these visits. And, of course, most do not.

dsfp

David, I must have awakened in a parallel world that’s slightly different from the one in which I went to bed, because I don’t remember what my Ph.D. is in or which university it’s from, much less getting one! :-)

Even the young Carl Sagan wasn’t exactly encouraged by his family (at least at first) to become an astronomer; when his grandfather asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up and he answered “An astronomer,” his grandfather then asked, “But how will you make a living?” Also:

I wonder if part of the reason why most kids don’t pursue careers as astronauts, scientists, or engineers is because of subtle discouragement from their parents? Even engineers–despite the obvious (in every house, car, business, and community) contributions that their work makes to everyone’s lives–are mostly thought of (and portrayed as) nerdy, often boring misfits who have obscure interests. (I have even read a saying by an engineer who reveled in that characterization, taking pride in it: “Engineers aren’t boring people–we’re just fascinated by things that other people find boring.”)

Astronauts and scientists are considered even further removed from “normal.” Unless a child has a strong innate interest in such subjects (and perhaps streaks of being a self-starter and a loner, not caring if s/he is “cool” or not), I can easily see how most children could be nudged or led away from such interests and careers. (I would never want to see children who are interested in other things to be pressured into these fields; I just hate to think of how many potential engineers, scientists, and astronauts we may lose because of social pressure in the other direction.)

The “Space Race” was only incidentally a contest of national ambition and prestige. It was based in the calculations of the Cold War- in the belief that manned spaceflight and heavy-lift capacity would be of immediate and vital importance to the strategic balance between the superpower blocs. In particular, the belief that both offensive nuclear weapons and elements of anti-ballistic missile systems would be based there. The Apollo program was originally envisioned as the creation of a system of launchers and vehicles that would permit US personal to conduct intelligence/strategic missions anywhere in orbital and cislunar space. Among the more grandiose visions was the establishment of a manned USA nuclear missile base on the Moon, which to build and maintain was slated to require 25 Saturn V launches per year (!)

This vision faded when it became clear that keeping nuclear warheads housed in missile silos on Earth was a far more practical option, and that operations previously thought to require a manned presence i.e. reconnaissance could be done almost as well and vastly cheaper by remote control. The Space Race in terms of strategic/military competition between the USA and USSR ended with the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, in which the signers agreed not to base nuclear weapons in space or nationalize bodies beyond the Earth. The real purpose of Apollo had ceased to exist before the first moon landing even took place. This is what caused the “indifference” to space post 1972.

In the 1980s there was a surge of renewed interest when it was believed that the Space Transportation System (“Shuttle”) would allow economical and routine access to space, in support of both civil (O’Neill’s High Frontier colony proposal) and military (Strategic Defense Initiative a.k.a. “Star Wars”) projects. But these foundered when the Shuttle proved to be hopelessly uneconomical.

In both cases spaceflight development was dominated by a bureaucratic “top-down” model attempting to achieve ad hoc goals by fiat, which ultimately failed in much the same manner that planned economies failed in Communist countries. The current period of renewed interest in space is categorized by attempts to apply the free market model to spaceflight, which may at last produce a launcher/vehicle infrastructure capable of organic growth and adaptation.

Just for the sake of completeness, shouldn’t there be an “obsessively spacefaring civilization” to complete the picture?

I could see a civilization arising on the only vaguely hospitable planet, in a system otherwise lacking in significant space resources. No Moon in their sky to serve as a goal, no terrestrial planets available to dream about, no asteroid belt. Maybe some gas giants, but no intermediate stepping stones.

Make that first step from orbit to something else useful in space big enough, and a civilization might stop at communications and weather satellites, and never dream of the planets, let alone the stars.

Yes, definitely, a study of obsessively spacefaring civilizations would complement the picture I have painted of indifference. S. Jay Olson has done something like this in a series of papers in which he develops the idea of aggressively expanding civilizations.

It is an interesting thought experiment to explore the different spacefaring experiences that might be had by a civilization with no “immediate stepping stones.” The particular contingent circumstances in which a civilization arises probably has a lot to do with the shape of its subsequent history.

I see the current discussion of a space-faring nation in terms of a never-happened scenario of earth-bound exploration and colonization. Imagine that sometime around the end of the first millennium someone went to the king and said, “Let us build a ship to sustain a crew in safety and sail to all points of the compass to see what is there, to settle new lands . . .” Why not concentrate on a return to the Moon and establish a sustainable presence for exploration and commercial development. If we cannot do that little step, we surely cannot reach another star. It may be that travel between stars will always be beyond any civilization. But surely we can explore and possibly colonize and exploit other parts of our own solar system. A domed city on Mars is far more plausible at the present time than are interstellar voyages.

“A domed city on Mars is far more plausible at the present time than are interstellar voyages.”

And than a Moon colony. The Moon is a desert. Mars is much much easier.

Think of the Moon as a filling station, training camp, vacation spot, and observatory. It won’t be a major colony but it’ll be useful.

A spacefaring civilization might be entirely contained within its home planetary system and still be a spacefaring civilization, i.e., a spacefaring civilization does not imply interstellar spacefaring, although if a spacefaring civilization within a planetary grew sufficient large it would reach outward to the Oort Cloud and beyond, and at that stage it is almost half way to another star. At this stage in our development the difference between spacefaring within our planetary system and interstellar spacefaring seems like a giant leap, but I don’t think it will always seem so.

The “central project of a civilization” concept only has [forced] historical analogies for civilizations that are centrally ruled and controlled. Liberal civilization does not work that way. It supports many possible “projects”, which may change frequently. As economic and political power shifts to merchants (corporations), civilization supports many long-term projects. The example of Apollo was hardly a “central project” of even the US, and had such a short-term life of a decade that it will hardly be noted in deep time histories (although the Moon landing should be).

If “the economy” remains central to how states run, with corporations defining and driving it, then the ecosystems that support certain functions, e.g. transport, communications, will develop and change based on where profits are to be made. Today global transport is dominated by [container] shipping for food, resources, and goods, while people use aircraft. Should the economy start to demand space resources, we will likely see spacecraft developed to meet those needs profitably. Space commerce will develop different types of craft depending on cargo – resources or people. While this may appear to fit the “economic indifference to spacefaring” model, I think we are better served as just seeing this as the development of an economic based system. Because the mantle of long-term projects now falls on the shoulders of economic actors, whether we become a true spacefaring civilization will depend on how economies develop. We think we know that the cost of access to space is a likely constraint to space commerce, therefore reduced costs using new technology will show the truth or falsity of that belief. Solving the problems of speed and safety for human transport will be as important to spacefaring as the development of ocean-going ships was to global trade. If our current spacecraft are at the Kontiki or Ra stage of development, then we might hope for a progression of development that mimics the caravel, galleon, clipper, steel steamship and the contemporary container and cruise ships if the economy demands such vessels. If the economy becomes mostly non-materialistic, we may never develop such ships and never become a true spacefaring civilization, although a future one might become one.

Just as fish never became “landfaring animals” but evolved new forms to populate the land, it may be that only our intelligent machines will develop a true spacefaring civilization. Baxter and Reynolds “The Medusa Chronicles” depicts one such future, and Benford’s Galactic Center Saga novels another on a far greater scale.

When I use the term “projects” in “central projects” I am not referencing specific finite tasks like building a dam or a space program like Apollo. If that were the case, no civilization so defined could endure beyond the few decades it might take to complete the largest imaginable public works program.

As an example, medieval Christendom was engaged in a great many projects such as building cities (in its later phrases), crusading enterprises, assembling great universities like the University of Paris or the University Oxford. These are manifestations of a central project, and not themselves central projects. The central project of this civilization was the western Latin interpretation of Christianity, and this endured until the Protestant Reformation ended the medieval synthesis that had prevailed from the end of classical antiquity up to that time.

Similarly, liberal civilization is engaged in a great number of diverse projects, but most of these projects are manifestations of the Enlightenment project, whether in its destructive form of extirpating feudal institutions, or its constructive form of recognizing the autonomy of the individual, the expansion of intellectual inquiry, etc.

Arguably, liberal civilization is the most centralized civilization ever to exist in our planet’s history. We’ve seen so many illustrations of the pyramid of feudalism that we think of feudal societies as top-down centrally controlled societies. They weren’t. Power was extremely widely distributed in feudal networks, and these networks pervaded every aspect of life. Most people never saw a feudal lord higher than the local baron. There might be rumors of a distant king, but this had little to do with local life.

The shift to centralization emerges during the early modern period, especially with the French monarchy, which reached its apogee in the “Sun King,” so called because everything in the court and the country revolved around him. This level of centralized control was impossible in earlier civilizations due to the lack of modern transportation and communication systems. However, today, with our central governments and instantaneous communications between center and periphery, laws and policies once only enforceable within the confines of a capital city can now be effectively pushed to the boundaries of a nation-state (and so embody the territorial principle in law; non-centralized societies often recognized the personal principle in law, whereby the individual was judged by the ethnic community to which they belonged).

Liberal civilization has inherited this model of the centralized nation-state and is in the process of transforming this into a universal surveillance state (Foucault’s Panopticon) in which every single one of the state’s manifold projects refers back to a centralized system of control.

There could be species whose version of civilization has been achieved not by expanding territory but by constantly reworking societies within their territories. That could still result in innovation and creativity but it’s hard to see how they’d get anywhere else.

Maybe on a planet similar to Earth but larger with much stronger gravity.

We couldn’t even deal with them face to face except electronically unless we have workable teleportation.

I read your medium piece: Civilizations and their Central Projects>/a>.

It isn’t clear to me that specific projects, e.g. “building pyramids” do not constitute a central project based on that essay. Similarly, while you claim that constructions, e.g. cathedrals, may be a manifestation of the central project, it is hard to make the simultaneous claim that this central project can be created without a centralized control. In Medieval Europe, this was the Catholic church, an institution that still exerts control from the Vatican. It was they that drove your claim of the

I find it hard to see the connection between a “Liberal” (in the classic sense) state and the surveillance state which is authoritarian. While The Enlightenment remains an important idea in western civilization, that doesn’t seem to be a “central project” from your essay, and the diverse interpretations politically, economically and religiously seem to further contradict the “central project” concept. I see no way to falsify the central project hypothesis based on what we see in western civilization today.

Perhaps the basic core concept of western civilization today that is shared is that of continued economic growth. This has primarily evolved from the industrial revolution that allowed civilization to break from its Malthusian state. The manifestations of that growth are highly variable with competing ideas on how to support that growth. I doubt that historians will be able to point to just a few manifestations of that idea comparable to the pyramids or cathedrals.

People who believe in cyclical history usually give each culture a central project or formulation. I’m not an advocate of their interpretations though people will follow the easiest and most often done procedure in dealing with problems. I.e. if another country attacks yours fight them or give up; if the overall climate worsens either adapt technologically or migrate.

I tend to view societal development from a loosely thermodynamic perspective, roughly analogous to the particles of a gas gradually filling all available nooks and crannies and niches of the available phase space, consistent with global laws. Viewed thus, there will always be some Musks and there will always be some amygdalic conservatives, with the vast majority of us plodding along in relative mundanity, seeking a consensus equilibrium.

I see the drive for interstellar exploration as on equal footing with the drive to build out in this, our home solar system, this latter with the long term goal of pushing Earth (at least) further out as the sun warms and balloons.

As the line increasingly blurs between AI/robotics/nanotech and transhumans, the distinction between “manned” and “unmanned” exploration blurs into a continuum. Delivering “humans” to the stars on light beams at tens of thousands of gees initial acceleration is already within our capability to imagine in 2018. Using Sol’s gravitational focus on superintelligent transhuman mites to sustain the acceleration longer, promises far shorter trip times across the galaxy.

The cooling off of the space race has left us with many interplanetary satellites, probes or automated, computerized interplanetary missions. We don’t have to have manned flight to be spacefaring. The disillusionment from the fact that there are no colonizable planets and planets which have environments suitable to life in our solar system has stimulated the desire to look for worlds in other star systems, and that has accelerated technological advancement and new ideas such as breakthrough projects. It would be nice to see manned spaceflight progress at this same rate and there still is VASIMR and the future.