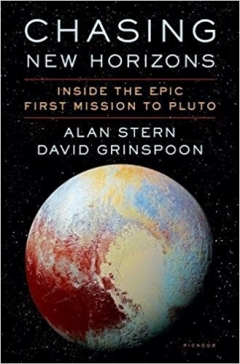

Chasing New Horizons, by Alan Stern and David Grinspoon. Picador (2018), 320 pp.

Early on in Alan Stern and David Grinspoon’s Chasing New Horizons, a basic tension within the space community reveals itself. It’s one that would haunt the prospect of a mission to Pluto throughout its lengthy gestation, repeatedly slowing and sometimes stopping the mission in its tracks. The authors call it a ‘basic disconnect’ between how NASA makes decisions on exploration and how the public tends to see the result.

‘To boldly go where no one has gone before’ is an ideal, but it runs up against scientific reality:

…the committees that assess and rank robotic-mission priorities within NASA’s limited available funding are not chartered with seeking the coolest missions to find uncharted places. Rather, they want to know exactly what science is going to be done, what specific high-priority scientific questions are going to be answered, and the gritty details of how each possible mission can advance the field. So, even if the scientific community knows they really do want to go somewhere for the sheer joy and wonder of exploration, the challenge is to define a scientific rationale so compelling that it passes scientific muster.

Thus Alan Stern’s job as he began thinking about putting a probe past Pluto: Get the scientific community to see why Pluto/Charon was a significant priority for the advancement of science. And as this hard-driving narrative makes clear, advancing those priorities would not prove easy. But a few things helped, including the spectacular coincidence that Charon was discovered (by Jim Christy in 1978) just before it was about to begin a period of eclipses with Pluto, a period that would not recur for more than a century. When the eclipses began in 1985, Pluto was suddenly highly visible at planetary science conferences and we were learning a lot.

Chasing New Horizons follows Alan Stern’s efforts to use ensuing discoveries like the different composition of surface ices on Pluto and Charon and the observations of Pluto’s atmosphere to draw attention to mission possibilities. Beginning with a technical session at a American Geophysical Union meeting in 1989, Stern began arguing for what would become New Horizons, brainstorming with key Pluto scientists who would become known as the Pluto Underground on a mission the authors describe as “a subversive and unlikely idea, cooked up by a rebel alliance that seemed ill-equipped to take on an empire.”

It would prove to be quite a battle. A letter-writing campaign would develop, leading to an official NASA study of a possible Pluto mission, one led by Stern and fellow Plutophile Fran Bagenal, working with NASA engineer Robert Farquhar (who would die just months after the actual Pluto flyby). From here on it was a matter of keeping the mission visible, from pieces in Planetary Society publications to continuing talks at major conferences, where attendance was growing.

I won’t go into the intricacies of such entities as the Solar System Exploration Subcommittee, which would analyze the Farquhar report, or the personnel changes within NASA that affected the work — for that you’ll need to read the book, where the action becomes something of a pot-boiler given all the roadblocks that kept emerging, including mission cancellations — but as the New Horizons mission took early form, Pluto was likewise on the mind of engineers at JPL, who began concurrent work on a mission concept. NASA’s turn toward Rob Staehle’s Pluto Fast Flyby design was just one in a series of course changes for Stern and team. A Pluto Kuiper Express concept followed, then the formation of a NASA Science Definition Team.

Here’s a sample of how frustrating the on-again, off-again nature of New Horizons’ birth appeared to its proponents. Budget considerations had caught NASA’s eye and in the fall of 2000, a ‘stop-work order’ went out on all Pluto efforts:

Those of us who’d been working on it felt like we had been through a decade of hell running errands, with endless study variations from NASA Headquarters [says Stern]. How many iterations of this, how many committees had we been in front of, how many different planetary directors had we had at NASA, how many different everythings had we put up with? Big missions, little missions, micro-missions, Russian missions, German missions, nonnuclear missions, Pluto-only missions, Pluto-plus-Kuiper-Belt missions, and more…

New Horizons, as it would do repeatedly, came back to life, and we all know the result, but the first half of Chasing New Horizons is a fascinating and cautionary tale about how difficult mission design can be in a charged environment of tight money and competing proposals. Science surely had the last word again, because the need for a mission was now pressing, given that Pluto was moving further from the Sun in its orbit, its atmosphere could conceivably freeze out before a mission got there, and visibility considerations involved Pluto’s sharply tilted spin axis (122 degrees) and its effect on lighting across the globe.

As to the actual approach and flyby, you’ll find yourself back in those heady days, when the earliest images from New Horizons gradually gave way to more and more detail, and the stakes continued to rise even as the unexpected threatened to stymie the close approach. Exhaustive hazard searches helped Stern’s team scout the system, but the critical Core load — the lengthy command script that would get the spacecraft through its scientific observations — had to be uplinked. New Horizons received the Core load and then suddenly went silent.

Quick diagnosis made it likely that the spacecraft would restart using its backup computer, which did occur within a short time, but with the flyby near, timing was critical:

As more telemetry came back from the bird, they learned that all of the command files for the flyby that had been uploaded to the main computer had been erased when the spacecraft rebooted to the backup computer. This meant that the Core flyby sequence sent that morning would have to be reloaded. But worse, numerous supporting files needed to run the Core sequence, some of which had been loaded as far back as December, would also need to be sent again. Alice [Bowman] recalls, “We had never recovered from this kind of anomaly before. The question was, could we do it in time to start the flyby sequence…?”

With three days to do the job, the equivalent of weeks of work had to be done in three days. The task was completed with just three hours to spare. Exciting? Believe it. David Grinspoon’s method in Chasing New Horizons was to synthesize the thoughts of Alan Stern and others on the mission within a narrative that captures the drama of the event. Grinspoon is a fine stylist — search the archives here for my thoughts on his exceptional Earth in Human Hands (2016), and I’ve also written about his earlier book Lonely Planets (2003). Here he goes for clarity and narrative punch, presenting Stern’s insights inside an almost novelistic frame. This is a book you’ll want to read as we approach MU69.

It will be a sad day when the Chinese land a man on the Moon and the public angrily wonders why NASA hasn’t already set up a research station near the US flag on the Moon…It will take 1000s of years to visit the stars without FTL Politics is never factored into the equation of spaceflight…robot or otherwise…voyages to the stars will be preceded by setting up a research station on the Moon…That’s just politics…

Apparently the general American public doesn’t want to put humans on the Moon and Mars, so if someone else does, they have little to complain about:

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/casey-dreier/2018/0606-nasa-is-beloved-the-moon-not-so-much.html

Chris Hadfield joins the ranks of astronauts like Aldrin in promoting public/private space activities. He makes his case for a base on the Moon.

In retrospect, the “space race” pitting 2 governments against each other derailed the very process for private development that is now gaining ground. Peacetime uses of Outer Space(pub. 1961) ed. Simon Ramo had at least one contributor make the very same case for private enterprise as we are making today [ch. 10. Competitive Private Enterprise in Space – Ralph Cordiner]. It is increasingly clear that Nasa should not be in the game of managing the development of rockets and spacecraft, but rather focus on pathfinding (map making), crucial enabling technologies, with government support for nascent industries to build markets. Whether they succeed or not, Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin are trying to develop some sort of space tourism business. SpaceX has grander dreams, which I hope will push the industry forward whether SpaceX succeeds or not. They have certainly pushed reusable rocket technology and lowered costs further than existing aerospace companies, and if they can pull off the BFR, then they will be well out in front.

Maybe we are finally getting back on track. If so, “Game on!”.

We still live in an age where the cost of technology and access to space is so high that any mission is a marathon of justification, planning and finally execution, not always with complete success. We are as spellbound at what these probes return as those in earlier centuries were with the return to port of global exploration ships.

Assuming technology trends continue, we might expect that much of this expensive technology becomes “off-the-shelf”, and even miniaturized to fit into a relatively small chassis. Access to space will become as cheap and commonplace as parcel mail.

I have no idea how long that would take, but I wonder at some future when almost anyone/institution can construct/buy and send space probes to any target in the solar system, managed by an AI using low-cost communication and transport infrastructure. Such probes might be as ubiquitous as web and security cams, or smartphones are today. These probes won’t displace the then current high technology probes any more than smartphones displace server farms or mainframes, but will offer a ubiquity that will make the solar system, as transparent and accessible as Earth is today.

A decade or more ago, Nasa started sending video streams from the ISS. A decade from now, wall screens will be able to display high definition live streams from anywhere, including space assets. No doubt Mars’ panoramas will be popular, as will Earth from orbiting platforms. But how long until the chill landscapes of Europa or Pluto, or the barren surfaces of tumbling asteroids be available? How long before the data streams provide AR overlays and stream 3D imagery to VR glasses allowing one to gain an impression of being there?

ljk commented in the Juno post:

Perhaps it is time to make such streams, visual and also data reading, commonplace, both for citizen scientists and for entertainment.

Jason Davis • June 11, 2018

Meet MMX, Japan’s sample return mission to Phobos

You may have heard that both NASA and China have plans to return samples from Mars. NASA’s Mars 2020 rover will curate a cache of samples for future retrieval, while China is kicking off their Mars ambitions in 2020 with an all-in-one orbiter, lander and rover. Both missions could wrap up before or around 2030.

But did you know there’s also a Phobos sample mission in the works? Meet Japan’s Mars Moons eXploration mission, also known as MMX, which will launch in 2024. MMX will study both Phobos and Deimos and collect a sample of Phobos for return to Earth in 2029. Japan’s not going to Phobos, alone though; NASA is providing a key instrument that will get in on the fun.

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/jason-davis/2018/20180610-meet-mmx.html

Pity the Russian Fobos-Grunt mission failed back in 2011, or we would have answers already.

Gotta love how the Russians continued the Soviet tradition of blaming any and all failures with their spacecraft on anything but their own technical issues.

To quote from the Wikipedia article you linked:

Aftermath

Initially, the head of Roscosmos Vladimir Popovkin, suggested that the Fobos-Grunt failure might have been the result of sabotage by a foreign nation.[67][68] He also stated that risky technical decisions had been made because of limited funding. On 17 January 2012, an unidentified Russian official speculated that a U.S. radar stationed on the Marshall Islands may have inadvertently disabled the probe, but cited no evidence.[69] Popovkin suggested the microchips may have been counterfeit,[70][71] then he announced on 1 February that a burst of cosmic radiation may have caused computers to reboot and go into a standby mode.[72][73] Industry experts cast doubt on the claim citing how unlikely the effects of such a burst are in low Earth orbit, inside the protection of Earth’s magnetic field.[74]

On 6 February 2012, the commission investigating the mishap concluded that Fobos-Grunt mission failed because of “a programming error which led to a simultaneous reboot of two working channels of an onboard computer.” The craft’s rocket pack never fired due to the computer reboot, leaving the craft stranded in Earth orbit.[75][76] Although the specific failure was identified, experts suggest it was the culmination of poor quality control,[77][78] lack of testing,[79] and corruption.[80] Russian president Dmitry Medvedev suggested that those responsible should be punished and perhaps criminally prosecuted.[70][81][82]

Their screw up also cost the Chinese their first chance to send a space probe to Mars:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yinghuo-1

They also doomed a panspermia experiment:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Living_Interplanetary_Flight_Experiment

Roscosmos had a number of problems, including launch failures. The organization needed a shakeup, and may still need one. Popovkin, or his predecessor, can be thankful they did not work in North Korea. Failure there has far more drastic consequences!

I take it from this that an Eris mission will not occur within the lifetime of many, if not most, people now alive.

Perhaps contacting Elon Musk might resolve that issue.