As we continue to track the Voyagers into interstellar space, the spacecraft have become the subject of a new documentary. Associate editor Larry Klaes, a long-time Centauri Dreams essayist and commentator, here looks at The Farthest: Voyager in Space, a compelling film released last year. Larry’s deep knowledge of the Voyager mission helps him spot the occasional omission (why no mention of serious problems on the way to Jupiter, or of the historic Voyager 1 photo of Earth and Moon early in the mission?), but he’s taken with the interviews, the special effects and, more often than not, with the spirit of the production. That spirit sometimes downplays science but does give the Golden Record plenty of air-time, including much that was new to me, such as the origin of the “Send more Chuck Berry!” quip, John Lennon’s role, NASA’s ambivalence, and an odd and insulting choice of venue for a key news conference. Read on for what you’ll see and what you won’t in this film about our longest and most distant mission to date.

By Lawrence Klaes

Can one properly represent humanity to the rest of the Milky Way galaxy with just two identical space vessels no bigger than a small school bus and two identical copies of a golden metallic long-playing (LP) record attached to the hulls of said vehicles which contain in their grooves sample images, sounds, languages, and music of their makers and their world?

Our species can only hope so at this point, since the objects in question left Earth over four decades ago and are now tens of billions of miles into deep space heading in different directions through the galaxy. Although primarily planned and built to explore the planets, moons, and rings of the outer Sol system, these vessels were ultimately given another purpose and destiny preordained by their encounters with the places they were sent to. Ironically, this destiny relies on the existence of beings for whom there is as yet no evidence that they are actually out there among the stars.

These records, their carrying vessels and their missions are the focus of the documentary The Farthest: Voyager in Space, which premiered in 2017. Written and directed by Emer Reynolds and produced by John Murray and Clare Stronge for the Irish documentary company Crossing the Line Productions, The Farthest does a masterful artistic job of introducing to generations who were either too young or not yet born to two real space probes on actual missions to alien worlds on a scale never attempted before.

Pioneers and Voyagers, Plaques and Records

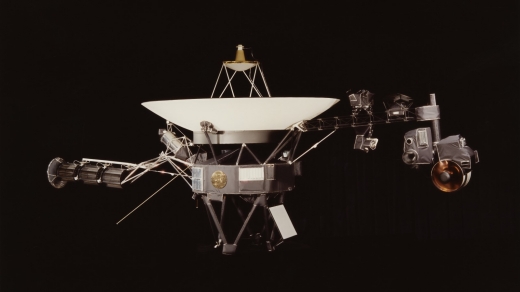

The “stars” of The Farthest were originally designated Mariner 11 and 12 by their creators at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). They were the descendants of a successful lineage of American deep space probes which had in their ancestry the first visitors to the planets Venus and Mars. However, the space agency wanted to “spice” up their public image and recast these newest members of the Mariner clan as Voyager 1 and 2.

The renaming was appropriate, for these sailors of the interplanetary seas were also descended from what remained of the original Grand Tour plan of the 1960s to examine the outer worlds of the Sol system from Jupiter to Pluto with four nuclear-powered space probes and return unprecedented magnitudes of data about them on a selection of wavelengths.

Launched from Earth in the late summer of 1977, the interplanetary trajectories of the Voyagers past the gas giant worlds would eventually fling them fast enough to permanently escape the gravitational influence of our yellow dwarf star. This would make them only the third and fourth space vessels made by humanity to head towards the interstellar realm after Pioneer 10 and 11, the members of another line of automated American space probes with an impressive exploration pedigree which had celestially paved the way for their more sophisticated brethren just a few years earlier.

The nearly twin Pioneer probes were not only the first spacecraft to visit the planets Jupiter and Saturn between 1973 and 1979, they were also the first to be the recipients of gravitational “slingshots” by those gas giants that sent them towards interstellar space. In case either or both of the probes might one day be found drifting between the stars by sophisticated alien intelligences, each Pioneer carries a small golden plaque attached to their antenna struts. A scientific greeting, the plaques are engraved with basic information on who made these vehicles, what their missions would be, where the probes came from, and when they were lofted into the void.

Recognizing the Voyager missions as two more rare opportunities to preserve and present selected aspects of their species to the wider Milky Way, a small group of professionals from a variety of fields (several of whom were involved with designing the Pioneer Plaques), thinking far ahead, planned and put together a more intricate and detailed “gift package” in the form of a gold-plated copper record. Protected by a thin aluminum cover inscribed with pictogram instructions on how to play it, the Golden Record (as the Voyager Interstellar Record is most often called) contains as much information as could be reasonably etched into the spiraling groove of the 12-inch disc, with over half of the data about the human race being selections of global music.

It has been conservatively estimated that the side of the Golden Records facing outwards (they are bolted to the exteriors of the probes’ main bus) will survive in playable form for at least one billion years in deep space, barring any remote chance of a large cosmic collision or other accident. Hopefully this will be more than enough time for someone to come upon the vessels and their priceless cargo before the galactic environment wears them away to join the rest of its voluminous interstellar dust.

Although the Golden Record was certainly not the main reason for the Voyager missions, they have long since become the prime focus in the public’s mind. After all, the probes’ primary missions ended when Voyager 2 flew through the Neptune system in 1989 and even though they are still functioning and collecting in situ science data on the interstellar medium, that current mission will end around 2030 when their nuclear power supplies can no longer generate enough energy to run any of the instruments. This will leave the Voyagers with its final, singular purpose: To carry that shining circular gift throughout the stars for eons, with the slim but still hopeful possibility that some day another mind in the galaxy will discover it and learn about us.

The Farthest as a Whole

The Farthest is a beautifully crafted documentary on a subject that has been waiting a long time for a proper and respectful treatment. Emer Reynolds love for the subject is evident, inspired by childhood visits to her uncle’s farm in Ireland with its night skies free of light pollution, as she described in this interview:

“A fascination with space began on those farm stays. ‘Mohober House’s sky at night was the opposite to the skies over our home in Dublin. We would drive to Tipperary in our old Hillman Hunter, my dad doing maths puzzles with us all the way, just for fun.

“As night fell, the dark, dark skies overhead would reveal the sparkling cosmos. I was dazzled and in awe of the visible smudge of our Milky Way Galaxy overhead.

“I would spend hours lying on the grass, staring into the blackness. I was dreaming of tumbling through space, hurtling along at 67,000 mph, clutching onto a fragile blue planet.

“Aliens, Horse Head Nebula, star nurseries and time-travel, and exotic distant worlds filled my head as a child. They still do in fact.

“The film is a love story to that awe and wonder I first felt as a child in Tipperary,” Reynolds said.

With its under two-hour running time, The Farthest manages to perform quite the balancing act describing the forty-plus year history of how the Voyagers came to be and what they accomplished. This presentation included interviewing nearly two dozen people, most of whom were either directly involved with the development of the space probes and their science missions, or the creation of the Golden Record – and sometimes both. The documentary goes back and forth between the birth, development, launch, and missions of the Voyagers to the four gas and ice giant worlds dominating the outer realm of our celestial neighborhood – Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune – and the parallel development and contents of the Golden Record.

Had Reynolds et al the time and resources, it would have been fascinating to turn The Farthest into a multi-part documentary. For although the production succeeds in giving an excellent introduction to the overall mission, accomplishments, and the people of the Voyager expeditions, each aspect of these deep space probes could have been given their own documentary for a truly in-depth treatment.

As someone who has followed the Voyager probes since their conception in the Grand Tour plan, I was made keenly aware of various important moments in the Voyager history that were left out, no doubt due in large part to time. Each world system visited and revealed by our intrepid robot explorers could easily be given their own dedicated time.

Here is just one example: While the documentary did talk a bit about the true nature of Jupiter’s Galilean moon Europa, first made known to humanity by the Voyagers in 1979, it was literally just skimming the surface on this alien world. Europa has a global ocean of liquid water at twice the volume of all the water found on Earth that is perhaps sixty miles deep and hidden beneath a crust of ice covered in many long lines and cracks and very few impact craters in comparison. It has been speculated that the ruddy material which permeates these fractures in the ice are organic compounds churned up from the ocean below – and perhaps even include the remains of native aquatic life forms.

In regards to the technical aspects of the Voyager probes themselves, when considering how much The Farthest focused on all the technical troubles the twin Voyagers had when they were launched into the Final Frontier for extra dramatic effect, I was disappointed to witness no mention of the serious problems that Voyager 2 had with its radio receivers well before its one and only encounter with Jupiter.

In April of 1978, the space probe’s main radio receiver permanently failed after an unexpected power surge blew its fuses. Thankfully Voyager’s designers had installed a backup receiver which did activate automatically, although it took an entire week for this to happen as mission controllers had to wait for Voyager 2’s onboard computers to recognize that the probe was not receiving any commands from Earth.

Then the team discovered that the backup receiver was having issues of its own, namely that it could not detect changes in radio signal frequencies due to the failure of its “tracking loop capacitor.” As a result, the probe’s human handlers had to determine which frequency that Voyager 2 was listening to and then send commands on the available channel. This situation remained through every one of its planetary encounters right to the present day.

Had both radio systems failed, Voyager 2’s mission would have been effectively over before it had really begun. Both probes were sophisticated enough to conduct a basic science mission on their own in the event they lost contact with their human controllers, but without a way to relay their precious data back to Earth, no one would ever know what the Voyager had found out there. In the particulars of Voyager 2’s case, not only would we have lost its much closer examination of Europa but also humanity’s first encounters with Uranus and Neptune.

Seeing as we have yet to follow up with any new probe missions after Voyager 2’s singular flybys of those ice giants after a time span of over three decades, the loss to planetary science had the robot explorer gone permanently silent while sailing through the Main Planetoid Belt cannot be overestimated.

I was also surprised that the documentary made no mention, let alone failed to even show, one of the first historic actions one of the probes had done during its mission: Just thirteen days after being launched from Cape Canaveral, Florida, Voyager 1 aimed its cameras at the world it had just left and returned the first image of Earth and its moon captured in a single frame from 7.25 million miles away.

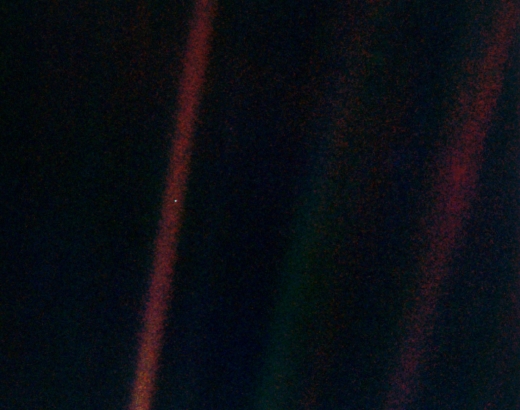

This is probably among the more famous images taken by the two deep space probes – and that is saying something. I wish the documenters had shown Earth and the Moon as Voyager 1 saw it while the robotic explorer was just underway on its long journey and then juxtaposed it with the later segment on the probe’s last image taken in February of 1990, the very famous photograph of our planet as a Pale Blue Dot as seen from the edge of our Sol system. This would have made for a nice counterpoint balance, bringing home just how far the Voyagers had gone not only in terms of distance but also in how much they had revealed to and enlightened the species that built them for this adventure, living back there on that blue globe now so far away in space and time.

The special effects in The Farthest were very nicely done. One standout in particular involved Voyager 1 sailing in front of Jupiter with its Great Red Spot while they played the eerie, screeching radio signals coming from the giant planet. These literally otherworldly sounds turned out to be immense electrical storms far bigger and more powerful than anything generated on Earth.

I also liked how they introduced the segment for each new planet as the Voyagers approached them for the first time. They took numerous still frames taken by the probes of the world as they were being approached and combined them into a video with subdued music playing in the background. This gave the viewer the feeling of how the mission team felt as the alien globes were slowly being revealed in increasing detail by the probes’ electronic eyes.

Another highlight of The Farthest were the interviews of the people who played both direct and indirect roles with the Voyagers and their Golden Records. Among the many standouts were Frank Locatell, Voyager’s Project Engineer, Mechanical Systems, whose expressive and amusing description of how the team had to surreptitiously wrap all of the probes’ external cables with aluminum foil bought from a local grocery store – so that Jupiter’s immense and powerful magnetic field wouldn’t fry the machines into electronic oblivion — is worth watching the documentary for that alone.

Nick Sagan, the third son of Carl Sagan, the famous astronomer and science popularizer who did much to make the Pioneer Plaques and Voyager Records a reality, shared his experiences and thoughts as a young boy who was asked to participate in the creation of the Golden Record. Among the sound sections on the LP were samples of 55 human languages greeting whoever would find the Voyagers and their gifts some day. Nick represented all those people who speak English with the phrase: “Hello from the children of planet Earth.”

The documentary made a point of mentioning throughout that the Voyager probes were over forty years old, meaning their technology was from the 1970s: The year 1972 to be precise, as the spacecraft designs had to be “frozen” five years before the probes’ launch dates. Perhaps to younger ears this seems positively ancient, leaving them to wonder how anyone back then, even NASA, could send automated spaceships billions of miles across hostile space to explore alien planets and moons in working order for more than a decade.

Rich Terrile, Voyager Imaging Science, visually brought home just how wide the technological gulf had become over the past four decades by producing a modern key fob and saying that the processing power of the computer chip inside this little device was comparable to the most advanced – and much larger – artificial brains of that earlier era.

As a nice counterpoint, this demonstration was immediately followed by a clip with Voyager Project Manager John Casani, who asked: “What’s wrong with ’70s technology? I mean, you look at me, I’m [19]30s technology!” Casani added that he makes no apologies for the “limitations that we were working with at the time. We milked the technology for what we could get from it.” Seeing how the Voyagers have lasted well beyond their initial planned encounters with Jupiter and Saturn from 1979 to 1981, with every intention of recording and returning scientific data on the interstellar medium for perhaps two decades more, no apologies are necessary, indeed.

Apparently all of the interviews with the Voyager team members and some of the others shown in The Farthest averaged about three hours each. This is yet another reason to have an entire documentary series on the Voyager probes so that those who want to can hear everything these space pioneers accomplished beyond their tantalizing clips. I also hope that the documentary producers have either already archived or will archive these valuable interviews for the benefit of our historical record on the early Space Age.

Too “Space-y Science-y”?

One surprise taken from various interviews and news items regarding The Farthest was the documentary makers’ desire not to get too “space-y science-y” with their presentation. Here is one example of this attitude straight from Emer Reynolds herself:

“We were trying to find people that would be prepared to talk to us, but more than that – because we wanted to make a film that was very human and tapped into the human side as opposed to dry science,” says Reynolds.

The film, she assures, is not aimed at the “space-y science-y types” – it’s for everyone. It is, at its heart, a human story. “It goes into the heart of what makes us human, the great mysteries that define our existence,” says Reynolds.

Not only are “space-y” and “science-y” not actual words in the English language (plus referring to those who do like such topics as “types” is a bit insensitive and ostracizing), but this flies in the face of the fact that the Voyager missions were all about science, not to mention made possible because of science!

I understand to a degree what the documentary makers were trying to say here, as science can be and has been presented by its practitioners in a fashion that is often less than palatable to those who are not indoctrinated in the various fields of knowledge, even including something as naturally exciting and wondrous as outer space. However, such a statement – and a grammatically poor one at that – does not speak well either about the makers’ perceptions of their audience or the knowledge and interest levels of the audiences themselves.

I also understand that they wanted to be inclusive with their viewing audience, but to throw science under the bus like that is not only an offense to the general public but especially those who would be drawn to the subject matter of their documentary because it is both about a historic time in space science and communicating with intelligent extraterrestrial life.

With the exception of the fact that I wish they would turn this documentary into a series to expand upon the various aspects of the Voyager missions, I thought they did a fairly good job of presenting the space science of each world they visited. They even discussed the wild magnetic field of Uranus, a topic that could easily have become bogged down by someone having to explain its physics to a lay audience.

On the other hand, this explains why the documentary’s discussions on ETI were fairly basic, sticking to standard viewpoints and ideas on alien life and their possible behaviors. I cannot say I was entirely pleased with their use of children’s drawings of aliens as background effects. They tended to focus on portraying extraterrestrials as literal bug-eyed monsters and the big-headed, thin-bodied types from innumerable UFO reports. These depictions only serve to infantilize the subject and keep it from being taken seriously by the scientific community and others. Such stereotypical and immature presentations of aliens certainly do not help the case for the existence of the Golden Records.

It is just sad that our culture is so “afraid” of science or anything that might go above their heads, as if they would get lost and confused rather than learn something new to expand and enlighten their worldviews. After all, isn’t that what space exploration is all about? And the Voyagers did that big time. Plus, if we want future generations of those “space-y science-y types” to forge new missions to other worlds in our vast Cosmos, then documenters and educators need to appeal to them to spark their interest and destinies as much as the casually curious viewer, if not more so.

On the Record

The makers of The Farthest worried that too much impersonal science in their documentary would turn away potential viewers, whom they perceived as uncomfortable with the subject matter. In an ironic contrast, a number of the makers and practitioners of the Voyager probes were even more concerned that one particular item being added to the twin vessels were of no scientific value at all.

Jared Lipworth, a consulting producer with HHMI Tangled Bank Studios, which collaborated with the production company Crossing The Line to present The Farthest, stated the situation succinctly in this interview:

“The scientists at the time, a lot of them, did not want to have anything to do with it,” Lipworth said. “They did not want it on [the spacecraft] and didn’t like it was getting all the attention. But that says a lot about humanity. It was as much for us as it was for any alien that might find it.”

The Farthest provides a good deal of evidence for these reaction to the Golden Records from the scientific and engineering quarters of the Voyager team. Several members confirm this during their interviews, including Frank Drake, the famed SETI pioneer who was also heavily involved with designing both the Pioneer Plaques and the Voyager Records. NASA also showed their ambivalence towards the records: In their early press releases depicting photographs and diagrams of the probes, the Voyagers were often shown with their sides which did not include the familiar disc, as if by hiding the record the space agency could avoid having to discuss it. Being perhaps the most relatable and intriguing aspect of the robotic vessels to the general public, this ploy naturally failed.

The documentary also revealed that the official NASA press conference for the Golden Record was shunted off to a nearby second-rate motel. Held just days after Voyager 2 was lofted skyward, record team member Timothy Ferris relayed how he and his fellow collaborators had to compete with the music and general noise from a Polish wedding going on nearby, separated only by a large partition. The scenario is initially amusing until you grasp just how insulting the whole production was to the record team and the concept. However, as with NASA’s attempts to hide the pesky disc within their media documentation, their efforts at obnubilation were ultimately futile.

The space agency did make one last attempt to physically remove the Golden Record from Voyager. Ferris, who was in charge of procuring the music selections, wanted to include a short engraved dedication message in the blank spaces of the record between its takeout grooves: “To the makers of music – all worlds, all times.” Ferris was inspired to do this by John Lennon of The Beatles, who in turn recommended his studio engineer, Jimmy Iovine, to help with the production of the records.

This seemingly harmless act did not sit well with NASA, as the words were not included in the very detailed specifications for the Voyager probes. The agency was ready to replace the records with blank discs. Only the intervention of Carl Sagan speaking with the NASA Administrator kept the Golden Records attached to their spacecraft. Using a bit of poetry, Sagan pointed out that the dedication was the only example of human handwriting aboard the Voyagers – although it would not surprise me if a few folks snuck in their signatures and perhaps even a note or two during the assembly process. This was and is a common behavior in the history of lunar and planetary exploration.

The Golden Records do indeed have scientific value – certainly to those who may find them one day, but also for humanity itself. They provide a sociological and psychological study of how we may present ourselves to others, in particular others who are highly intelligent but not necessarily human. Then there was the need for developing technologies and sciences to make these presentations viable aboard a spaceship that has to last a very long time drifting in the interstellar medium and remain readable by non-human beings. The records did not need to have a scientific reason to be a part of the Voyager missions despite the protests, but there they are along with several others, no doubt.

For someone like me, who has immersed himself for a lifetime moving about the worlds of science and the humanities/arts, it is hard to imagine how those who can dream of exploring the stars and all their unknowns – plus actually do something to make those dreams a reality – could simultaneously dismiss and even feel embarrassed and hostile to the idea of life elsewhere, including those capable of finding the probe and its shiny metal gift. However, as consulting producer Jeremy Lipworth said, this “says a lot about humanity,” which is the whole point for the existence of the Golden Record.

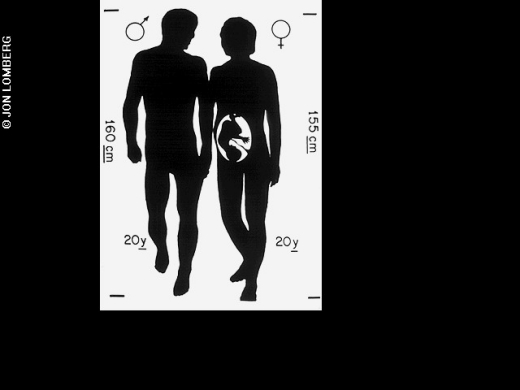

On the plus side, it was nice to see several Voyager team members defending what was on the Golden Records, in particular how certain images were not offensive despite public opinion and NASA’s concerns about offending those tax payers. This stemmed from the Golden Records’ predecessors, the Pioneer Plaques, which depicted a representation of a male and female human without any clothing upon them. People complained that the space agency was sending “smut” into space among other issues such as the positions of the man’s appendages compared to the woman, who just seemed to be standing there passively.

Having much more room to work with in comparison to the plaques, the Golden Records used this extra space to show any recipients how humans reproduce – within limits, of course. One photograph initially chosen showed a man and woman – nude again – holding hands and smiling at each other. The woman was clearly pregnant, or at least her condition is apparent to any adult human. NASA rejected this image out of fear of more public backlash, so Voyager Record team artist Jon Lomberg had to replace the tasteful photograph with a silhouette of the couple. This replacement at least had the advantage of showing the fetus developing in the woman’s womb as part of the reproduction story.

In a bit of irony, while the original photograph of the expectant couple was shown in the theatrical release of The Farthest, when the documentary arrived on PBS Television and elsewhere, someone had replaced the nude man and woman with the Lomberg silhouette! If you must see the original image, it may be found in the official book on the Golden Records titled Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record (Random House, 1978), authored by all of the main team members. This is a work that anyone interested in communicating with ETI and Space Age history must have in their library. It would be quite interesting to see how our contemporary prudery might affect the understanding of any record recipients when it came to explaining how the beings who made this by-then ancient artifact and its means of transportation also made copies of themselves.

Speaking of changes to The Farthest between its transition from the cinema to the television screen, I noted in the segment on the Pale Blue Dot where there is a vignette depicting various scenes of human activity on Earth, the whole piece was inexplicably removed from the documentary’s presentation on Netflix (it remained intact in its PBS incarnation).

The scene was a nice visual accompaniment on Carl Sagan’s wonderful explanation during a NASA press conference from 1990 of the last image Voyager 1 ever took, less than one year after its twin probe had successfully flown through the Neptune system. A celebration of human life on Earth in a series of wordless images set to music, it shows what we are, the good and the bad, without becoming too graphic in either direction.

This is somewhat ironic, as the Voyager Record team decided early on only to present the Cosmos with our best face forward so as not to inadvertently frighten or offend any recipients with our less sanguine qualities. Only some of the music pieces give hints to the records’ listeners that we are less than ideal, perfect creatures – though they may be able to figure this out anyway just by examining the Voyagers, which will undoubtedly seem incredibly primitive to them, since we assume those who find the space probes will be experts at interstellar travel and detecting small inert alien vessels in the dark and cold of deep space.

As for this unexpected edit to The Farthest, I must wonder if anyone at Netflix consulted with the documentary makers before making this cut, or if they just decided to second-guess the artists’ decision for reasons I do not readily see, either practical or aesthetic. Removing this celebration of the Pale Blue Dot may have done no permanent damage to The Farthest in terms of conveying information about the Voyager missions, but it did diminish a bit what made this documentary a cut above those works which are in essence a dry recitation of facts.

Having pointed out what was removed from The Farthest, this is a good time and place to state my desire for there to have been much more of and about the contents of the Golden Record in the documentary. Naturally they played samples of the record’s actual sounds, voices, images, and music throughout the film: The very first scene displayed a reproduction of part of the letter written by then U.S. President Jimmy Carter specifically for the Golden Record and its recipients. The interview with Nick Sagan gave an illuminating background as to what it was like putting the language segments together, at least in one particular case.

It was also fun to see the Saturday Night Live origin of the joke that any aliens who listened to the record would respond with “Send more Chuck Berry!” given by comedian Steve Martin. Later on we were treated to the amazing moment when, during a celebration of the wildly successful Voyager missions in 1989, both Chuck Berry and Carl Sagan got up together on stage at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, singing and dancing to the musician’s hit single, “Johnny B. Goode” – the only representation of rock-and-roll music among the Golden Record’s 27 international songs.

With the highlights of the positive aspects of the Golden Record as shown in The Farthest duty noted, this documentary made me realize just how much I wanted to see far more about that grooved disc and its contents. Just as its story could and did fill an entire book along with countless articles and stories in the intervening years, the Voyager Interstellar Record deserves its own film documentary to do it proper justice in presenting itself to the vast majority of humanity. After all, it was explicitly designed to be our representative to the rest of the Milky Way galaxy, so I say the species that it speaks for should be given the chance to really see the Golden Record should they so desire it.

Of the two hours of samples from humanity and our world, over ninety minutes of the record’s offerings are devoted to global music. The Farthest gave most of its time in regards to the music to Chuck Berry’s landmark song. Certainly at least for Western audiences, “Johnny B. Goode” was probably among the best known of all the record pieces. It also had the benefit of very relevant and entertaining visuals to go with it.

Berry’s pioneering rock-and-roll number was not the only well-known song on the Golden Record, however. Even those who may know little about Ludwig van Beethoven know at least the first few bars of his Fifth Symphony, which are now preserved for eons in deep space. As for my earlier mention of how the record music contains the few indications that humanity is an imperfect species, “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” by blues musician Blind Willie Johnson was chosen, in the words of Timothy Ferris in Murmurs of Earth:

“Johnson’s song concerns a situation he faced many times: Nightfall with no place to sleep. Since humans appeared on Earth, the shroud of night has yet to fall without touching a man or woman in the same plight.”

The final song on the Golden Record, which immediately follows Johnson’s number, was another Beethoven piece: The String Quartet No. 13 in B flat, Opus 130, Cavatina. It is a melancholy number made at a particularly dark time in the fading years of the composer’s life. However, this piece of music, like the being and species who made it, is neither simple nor provides simple answers to its meanings, as I quote Ferris once again from Murmurs of Earth:

“But sadness alone can’t define the Cavatina. Strains of hope run through it as well, and something of the serenity of a man who has endured suffering and come to terms with existence perceived without illusion.

“It may be that these ambiguities make for an appropriate conclusion to the Voyager record. We who are living the drama of human life on Earth do not know what measure of sadness or hope is appropriate to our existence. We do not know whether we are living a tragedy or a comedy or a great adventure. The dying Beethoven had no answers to these questions, and knew he had no answers, and had learned to live without them. In the Cavatina, he invites us to stare that situation in the face.”

There was also a recording of the thoughts of Voyager Record team member Ann Druyan conducted on an EEG machine, where she consciously pondered various historical ideas, events, and persons for one hour, along with “the exception of a couple of irrepressible facts” from her life. This part of the record’s development also did not appear in The Farthest, along with the conspicuous absence of Druyan herself. With both Druyan and Carl Sagan largely removed from having a direct influence on the documentary – Sagan passed away in December of 1996 from myelodysplasia, although clips of him conducting earlier interviews permeate the film and provide some measure of his presence there – I was left to wonder how the Golden Record might have been presented had the couple been around for their input, especially together.

The makers of The Farthest emphasized multiple times how much they wanted to bring out the human aspects of the Voyager missions. They did accomplish this, but as my examples have shown, there is so much more that was left untapped by this documentary which needs to be shared with the widest audiences possible. When you are trying to describe a complex and incredibly productive space expedition that is half a century in its making and undertaking in less than two hours aimed at an audience that is curious but not expected to be very knowledgeable about its subject matter, the best you can achieve is a sampler of the Voyager missions.

For those who care, The Farthest can only serve to whet one’s appetite for more. That a full-on documentary series or even a historical film (or mini-series) about the Golden Records has yet to be made after all this time is surprising, given all the depth, drama, and excitement that went into their realization.

I do not count John Carpenter’s 1984 science fiction film Starman as a proper answer to my request. Although it is a well-done film, the Golden Record only serves as the catalyst for the rest of the story. Besides, the film had The Rolling Stone’s 1965 song “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” as part of the music selection on the record, which is patently false. Plus, if the ETI captured Voyager 2 in space in 1984, this would presumably disrupt its mission to the planet Uranus two years later and Neptune three years after that. We did not witness if the aliens released the space probe back onto its flight path, but the visiting ETI’s scout ship was later found on Earth with the Golden Record inside it, thus denying other potential recipients of the Voyager the chance to encounter the disc and its contents, presuming the robotic craft was allowed to continue on its cosmic journey. The aliens interpreted the record’s messages as a peaceful invitation to our world, which they did with a representative of their advanced species – only to have their scout ship and its lone occupant shot down by a missile.

There especially needs to be driven home the fact that Voyager 1 and 2 are now on their final, ultimate mission as ambassadors of Earth and humanity to the rest of the galaxy. Yes, they are still functioning and taking important measurements of the interstellar medium, but the reasons they were sent into space in the first place are now long behind them. What the Voyagers did was both extraordinary and ground-breaking for planetary science, of course, but now other deep space probes have followed in their paths, with more sophisticated instrumentation and revealing data that surpasses their mechanical ancestors. That is the evolution of planetary exploration.

Humanity is a short-lived species, both individually and culturally. Human life spans average about eighty years at present, while we have only had any semblance of a civilized society for roughly six thousand years – mere drops in the cosmic bucket as the phrase goes. The Voyager Records will last for at least one billion years if not much longer even by conservative estimates of their survivability in interstellar space.

To contrast and compare: One billion years ago, Earth’s first multicellular plants were just starting to move onto dry land from the oceans. The evolution of more sophisticated terrestrial creatures were still hundreds of million years in the future. The Voyagers may even survive the demise of Sol and Earth, assuming our planetary system has not already undergone some radical transformation – natural or otherwise – before then.

This is why the actions of a relatively small collection of humans forty years ago to boldly charge into the void called space and simultaneously dare to imagine communicating with unknown alien intelligences in some unimaginable far future time – all with technologies that were becoming obsolete before they even completed their first mission milestones – are an incredible and deeply important story that must be told now and for the edification of our descendants. Sharing our past with our future should and must be done the way the Voyager missions and the Golden Records were put together, as a complimenting fusion of science and artistry.

The Farthest was a very good start, but the tale has hardly even begun.

To see more about this documentary along with the Voyager space probes and the Golden Records, visit the official PBS Television Web site.

A question Mr. Gilster , did the above “… the very famous photograph of our planet as a Pale Blue Dot as seen from the edge of our Sol system…” , what is the Red Line thru the Pale Blue Dot ??

The red line is one of several bands of scattered light in the image that NASA says is the result of taking the image so close to the Sun.

Here is what Carl Sagan had to say about that Pale Blue Dot in his 1994 book, which was also titled Pale Blue Dot:

http://www.planetary.org/explore/space-topics/earth/pale-blue-dot.html

Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there–on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.

— Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot, 1994

I really REALLY like the very inspiring remix of Johnny B. Goode they play over the end credits. Right after seeing the documentary on PBS I actually sought it out on the web, but alas it was unavailable. It seems that it was made specifically for the documentary. It is very hard to summarize Voyager in two hours in general, and despite whatever failings the documentary has I would congratulate the creators on a job well done.

The Farthest just won an Emmy for Outstanding Science Documentary:

https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/film/irish-film-the-farthest-wins-emmy-for-outstanding-science-documentary-1.3649255

Excellent review of a wonderful documentary. [I even got to learn a new word: obnubilation.]

I will, however, take issue with your concern that it didn’t do more to focus on the science of the mission. That it just won an Emmy suggests that it did target its audience correctly, at least as a commercial and artistic venture. Rightly or wrongly, people do not focus on the true purpose of many endeavors. How much of the focus on Columbus’ “discovery” of teh Americas focuses on the commercial reasons for the trip? Who visits Venice and wants to understand that it was a commercial/banking center, not a genteel architectural ruin, a role that Hong Kong more recently played and may in future resemble? That you also focus much on the Golden record, dismayed at the scientists who disliked its addition, suggests that you also care much about what it says about we humans.

I really liked the documentary, and will happily consume the science from other science-focused documentaries, textbooks, and even journal papers.

Actually, for the typical Greek Venice as a colonial power and its role in the Fourth Crusade is as important if not more important than its architectural heritage. We do go to San Giorgio Dei Greci which was only allowed to open because of the Greek mercenaries, the stradioti, that Venice employed. On the arsenal of Venice we do seek the Lion of Piraeus, stolen by Morozini when he destroyed the Acropolis of Athens and also note that this is where the fleet that ruined the Byzantine Empire sailed. There is always nuance in how people see things, especially when you climb up the education level. You are right though that the masses are more likely to focus on the record than the science, science though will bubble out eventually

Interesting cultural perspective. As a Brit, I think we were more influenced by the Romantic Period and the vision of Venice as a city in slow decay in the 19th Century. I don’t think that was a unique viewpoint either, as Mark Twain’s travelogues on his Mediterranean tour (“The Innocents Abroad) seem often to evoke similar feelings on his visits to ancient cities and monuments of once great powers.

3d bioprinting = Immortality = go to stars

The record is indeed a very important part, strange to hear that attempts were to remove it. It is a sign that we tried.

The chance or risk of the probe to be found in a timescale that could affect us and our civilization is very small.

If our civilization remain and develop without problems, we could have developed to anything beyond wildest dreams by the time the two Voyagers have traveled that far that ‘someone’ make the chance discovery of an ‘alien’ artifact.

The record might seem primitive compared with the way we store music and information today, but is actually a good choice as it will last longer – or at least parts of it.

Someone speculated that the music would be incomprehensible to aliens, I disagree, even if an alien race do not sing or make music, it is likely they have other species in their biosphere who do.

If that is the case, they might view us as a strange and extremely territorial intelligent species. Because song in the biological world, most often is to declare the locality is taken and that intruders will be attacked.

As a starry eyed child in the 80s I was thrilled when Voyager 2 reached Neptune but it’s the Golden Record which captures my imagination today.

One wonders what alien cultural delights might be on a probe heading towards Sol, what their Golden Record (if their minds and project managers allowed it) would be like?

Also, with the way things are going on Earth I will sleep easier when our great cultural works are digitised and stored off world, perhaps for raccoon descendants to marvel at in a million years!

I understand very well those who felt non confort with Golden Record existence, it has nothing common with science but more probably:

pride , narcissism of some involved in Voysger mission people…

The probability that some enigmas ETI could listen or even understand what to do with those records can be measured by imaginary part of complex number. But it is always good to be boss of the project , so you can implement your desires even if it has not connection to reality.

Regarding the science of the Golden Record, I will repeat what I said about that in my article here:

“The Golden Records do indeed have scientific value – certainly to those who may find them one day, but also for humanity itself. They provide a sociological and psychological study of how we may present ourselves to others, in particular others who are highly intelligent but not necessarily human. Then there was the need for developing technologies and sciences to make these presentations viable aboard a spaceship that has to last a very long time drifting in the interstellar medium and remain readable by non-human beings. The records did not need to have a scientific reason to be a part of the Voyager missions despite the protests, but there they are along with several others, no doubt.”

Who wouldn’t have a sense of pride regarding the Voyagers and their missions? The Golden Records created – and still create – a lot of positive feedback and also served as a welcome and necessary bridge between the practitioners of the humanities and sciences.

I am glad they were made and are traveling along with the Voyager probes, whether anyone ever finds them or not. They have already done much for many here on this planet.

I want to point your attention that I cannot agree with your point of view, sorry.

1. Your quote: “The Golden Records do indeed have scientific value – certainly to those who may find them one day”, I am sure that Voyagers have much order higher “scientific value” than “Golden Records”.

2. Your quote: “also for humanity itself. They provide a sociological and psychological study of how we may present ourselves to others”, sorry again, but this argument has no any value for humanity, because we will never know result of this experiment, it is not science. I am sure it could much more useful to test suppose method in the beginning on the Earth habitants that supposed to have intelligence (at least potentially) – homo sapience, dolphins, elephants, horses, dogs , cats, some birds, etc. As well as I know this methodology failed even with high IQ human beings…

3. Your quote: “The records did not need to have a scientific reason to be a part of the Voyager missions…”. If I understood this argument correctly – it was enough to have someone’s personal desire (someone who has significant influence on the project) . I see it was exactly as you wrote, agree it is not science.

4. Your quote: “The Golden Records created – and still create – a lot of positive feedback…”. Yes it is type of modern art – “Tastes differ”.

I suppose that after some 1000 years the “Golden Records” will be the same enigma ?ven to Homo sapiens, something like Stonehedge for us …

What heart does not soar at the mere mention of mission to the stars!

Thank you, Mr. Klaes, for the work you have done on behalf of all of us.

You are most welcome, Michael.

I’m glad that this was done and find it very interesting that the history behind it was so controversial. It seems now we have come full circle –

NASA SHOULD EXPAND THE SEARCH FOR LIFE IN THE UNIVERSE AND MAKE ASTROBIOLOGY AN INTEGRAL PART OF ITS MISSIONS, SAYS NEW REPORT.

Categories:Alien Life Oct 14, 2018

https://www.astrobio.net/also-in-news/nasa-should-expand-the-search-for-life-in-the-universe-and-make-astrobiology-an-integral-part-of-its-missions-says-new-report/

Please download a free Pdf copy of the report by signing in as a guest to download:

An Astrobiology Strategy for the Search for Life in the Universe.

https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25252/an-astrobiology-strategy-for-the-search-for-life-in-the-universe

Table of Contents

Front Matter i-x

Summary 1-7

1 The Search for Life in the Universe: Past, Present, and Future 8-17

2 Dynamic Habitalility 18-46

3 Comparative Planetology and Multi-Parameter Habitability Assessment 47-68

4 Biosignature Identification and Interpretation 69-94

5 Evolution in the Technology and Programmatic Landscape 95-109

6 The Search for Life in the Coming Decades 110-153

7 Leveraging Partnerships 154-165

Appendix A Congressional Mandate and Letter of Request 166-168

Appendix B Statement of Task 169-169

Appendix C List of White Papers 170-174

Appendix D Biographies of Committee Members 175-179

Appendix E Glossary and Acronyms 180-186

Nice to see that NASA is finally undertaking astrobiology and SETI again, especially after what they did to their SETI program from 1992 to 1993:

https://history.nasa.gov/garber.pdf

NASA also came out with this relevant document a few years ago – perhaps to test the waters:

https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/files/Archaeology_Anthropology_and_Interstellar_Communication_TAGGED.pdf

The Interstellar Journey of an Indian Raga That Has Been Playing for 39 Years Aboard the Voyager 1

by Sanchari Pal

February 23, 2017, 6:56 pm

Voyager 1 is special for one other reason. On board the spacecraft is a 12-inch gold-plated copper disc with music that aims to encapsulate 5,000 years of human culture. Compiled by American astronomer Carl Sagan, the songs of Sounds Of Earth (as the album is named) echo through outer space, billions of miles from Earth.

While most Indians have heard about this, few know that the album also includes a Hindustani classical music composition – ‘Jaat Kahan Ho.’ A hauntingly beautiful song by Kesarbai Kerkar, the legendary singer of Jaipur-Atrauli gharana, it is the only song from India that has been immortalised alongside the music of Beethoven, Bach and Mozart on the record.

Full article here:

https://www.thebetterindia.com/88645/interstellar-journey-indian-raga-kesarbai-kerkar-voyager-1/

To quote:

In 1977, the year Kesarbai passed away, the Voyager spacecraft carried her recorded voice to celestial heights. The poignant piece in raga Bhairavi asks the eternal question, Jaat kahan ho akeli gori (Where are you going alone, girl).

“A producer of the Voyager record, Timothy Ferris, once wrote about the Indian contribution to the mission in Murmurs of Earth, a 1978 book about the record. He says: “One of my favourite musical transitions on the Voyager record comes when ‘Flowing Stream’ ends and we are transported, quick as a curtsy, across the Himalayas to the north of India and from the sound of one musical genius, Kuan Ping-hu to another, Surshri Kesar Bai Kerkar. This raga is formally designated for morning performance, but its popularity has led to its use as a closing number, a kind of encore, for concerts day and night.”

It has been over five decades since Kesarbai last sang in a concert (she stopped performing in 1965), yet her music lives on, wandering through the unexplored terrains of outer space till perhaps the end of time.

Should we suppose that this wanderfull music records targeted to the intelligent beings that have never evolved sound waves sensors in their bodies or those one can hear sound waves, but in totally different frequency ranges? Or domeone suppose that recoded sounds has universal value for the whole Universe?

All I’ve wrote above is relevant in condition that misterious musical oriented ETI could understand what type of signal (if any) is represented on the gold tracks and how to recover it from the media…

More than 30 years ago I was spending lot if time listening vinyl records, in the beginning all vinyls that I had was recorded on 33-1/3 rpm, so when I for the first time purchased vinyl recirded on 45 rpm, I did not realized this fact and initially listened it on 33-1/3 rpm mode :-)

Yes it sounded somhow even more haevy metallic than on original speed… But it definitely can be recognized as wrong by someone who knkw well how human music should be sounded… ETI who supposed to be listeners of the Gold Records, knows about as nothing, even they will know as well this fact will not hepl them to “understand” our music if theyr sound sensors have different frequency range or their cognition processes are working with different speed…

Evolutionists sure – that it is more probable case of ETI we can expect.

So I suppose “the Golden Records” should have the better and more correct name – “Sagan’s Top-N records”

The Voyager Interstellar Record team had six weeks to put assemble their information package, put it on the Golden Record, and have the discs ready to be launched with Voyager 1 and 2 by late August, 1977. As one commenter said in the documentary, NASA was not going to hold their launches just to accommodate the records. Their immovable deadline was on a cosmic level.

As you read in my article, even though NASA allowed them to make the Golden Record and gave them a small budget to do so, the space agency paradoxically later tried several times and ways to rescind their offer. When those efforts failed, NASA then tried to subvert their very existence, which also failed.

Keeping all this in mind, you may then better appreciate the fact that the Record team was more than lucky to get not only some kind of information package onboard the Voyager vessels, but one that exceeded the original plan of a glorified Pioneer Plaque.

To accommodate all the possibilities of an alien recipient who may not have or use our types of senses would have been difficult to accomplish even if the team had ample time, money, and resources.

Compare this with the New Horizons team, who deliberately chose not to put even so much as a Pioneer Plaque on their space probe. However, not only did they find time to add various items aboard their vessels (such as a Pluto stamp and a Florida quarter), they were also able to include some of the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh, the astronomer who discovered Pluto in 1930.

http://www.collectspace.com/news/news-102808a.html

Now you know to put human remains aboard New Horizons took time, effort, planning, lots of permissions, and a stack of paperwork. Yet somehow the NH team said they did not want to do a real information package for their probe as it would apparently distract them from their main work. I am sure an outside team would have gladly done the task with minimal interference – just like with the Voyager Records.

With all due respect to Clyde Tombaugh, looking at the inclusion of his ashes strictly from the viewpoint of how its presence might be interpreted by any ETI recipients: What could they learn from a small sample of an actual human who has been reduced to a thimbleful of carbon? Besides learning that we are made of carbon and can be burned to ashes. Even the container the famous astronomer is interred aboard the deep space probe is written only in American English, with no other means or methods to translate what it says or to explain who and what is contained inside.

“the Golden Records”, “glorified Pioneer Plaque“ and “ashes of Clyde Tombaugh” – all those things are our (human being) strongly internal , homo sapience oriented and religion related thing, it is not science and even not SETI, it is human religious beliefs and superstitions consequence.

In addition it is good way for a “pseudo science” people to earn some funds for their “butter and bread”. As I can conclude from “the Farthest” story there was such people around NASA.

I understand very well why NASA people felt uncomfortably about “the Golden Records” , they knew more details about this issue and felt somehow ashamed.

It is good that “the Farthest” film tells us about those facts.

Are not all those things you list a large part of what makes up humanity? Is it really wrong to send along those aspects of ourselves with the vessels we made that will spend ages drifting without control through the Milky Way galaxy?

After all, whether you or anyone else likes it or not, those human drives are no small part of the reason that the Voyager probes and their Golden Records were conceived, built, and lofted into deep space along with the science, technology, and engineering that also made them become reality.

Even if who or whatever finds the probes and their records (and the Pioneers and their plaques, along with whatever else we send into interstellar space in the coming years) cannot directly decipher what is on our “gifts” to the Cosmos, they may be able to deduce certain things about the humans who made and launched them just the same.

Our human passions and even perceived weaknesses are what make us who we are, including our various space efforts – even if they tend to make certain people uncomfortable with such facts.

Your quote: “Is it really wrong to send…” , I don not thind it is totally wrong, but at first glance I suppose the final answer depends on some important conditions:

1. If “pop science” load does not harm or delay the main space exploration mission.

2. If “pop science” load does not harm the scientofic load.

3. In condition if “the Golden Records” supporter could fund Voyager project by their own money, i.e. compensate to NASA the expense of their “Golden Records”.

As I know – NASA spent additional funds for “the Golden Records” instead of possible additional scientific load.

It seams to me that in your arguments you are somehow equalizing importance Voyager probe scientific mission (space exploration) with ‘the Golden Records’ – cannot agree with this statement.

I wish that probes like Voyager will fly to the space every day, but feel very comfortly if none of “the Pioner plaque” nor “the Golden Record” will be attached to it.

And if “the Golden Records” attached to the new space probe it should be done on the additional sponsors fund, sponsor who will pay for the scientific mission, so could buy the honor to put on the probe something personal he(she) likes…

I remember , on this site , there was post about the plaque design for the “Breakthrough slightshot” sales (very problematic design IMHO). There is not any breakthrough and any sail , but fund has been already spent for the doubtful art design. If this approach will continue the same way, so I predict that there will be never built any real “Breakthrough slightshot” probe, but in same time I am sure , that all sponsors fund will be finally spent, till zero.

The Golden Record did not take away either funds or space for any scientific instruments on the Voyager probes. Not sure where you got that idea.

NASA allocated the record team a very small budget – $25K I recall. Some scientists and engineers may not have liked the idea of an information package for ETI (or future humans), but I do not remember any of them saying it deliberately or directly took away any science instruments from the probes.

I am also unaware that any budget has been spent on an information package for the Breakthrough Starshot concept, or even anything designed outside of some talk on this blog. Do you have evidence for this, or are you just assuming this happened based on your obvious concern for anything of such a nature? And if someone does have such a project on their own time and dime, how is that a problem for the interstellar mission overall?

You are also incorrect to assume that I put the Golden Records on equal importance to the Voyager probes’ scientific mission. As I thought I got across, the Voyager probes had and have three distinct major missions: The first was of course to explore the outer planets and their moons and rings. The second is to record data on the interstellar medium until 2030. The third and final is to serve as our “ambassadors” into the wider Milky Way galaxy, a mission they will be conducting for a very, very long time. Now if you go by time scales in terms of listing their mission importance, then the final one would naturally be on top.

The Voyagers did a great job exploring our outer planetary neighborhood. That mission is done and is now being superseded by more advanced vessels. The next one will be far longer and after 2030, there will be no further budget required for what they have to do next.

I happen to agree with you about how information packages should be conducted on all deep space probes. Because as we saw with New Horizons, if we leave it up to the mission team we may either end up with nothing or the equivalent of some small town’s time capsule. Or worse still, a bunch of signatures/names.

I also find it interesting that of all the things you could discuss about the Voyager missions, you have stuck steadfastly to the Golden Records. This further lends to their power and influence. :^)

On some you note I even do not need to write any my thought, enough to make quote from your text.

You wrote (ljk quote):

“The Golden Record did not take away either funds”.

And You answer:

(ljk quote) “NASA allocated the record team a very small budget – $25K”

Yes it is nothing if compare it with millions $ :-) But pretty enough for someone’s son “pocket” money …

ljk quote:

“I am also unaware that any budget has been spent on an information package for the Breakthrough Starshot concept”

There is the link below (from this site) :

https://centauri-dreams.org/2018/04/20/holographic-sails-for-project-starshot-homage-to-bob-forward/

ljk quote:

“you have stuck steadfastly to the Golden Records. This further lends to their power and influence”

Yes I am… I feel huge respect to the team that designed, built and sent Voyagers to their long travel, but in same time cannot share an exaltation about “the Golden Records” – shameful event (IMHO)…

I see also that ” their power and influence” – is overestimated .

Starshot has spent no money on an information package for the spacecraft. The article you reference, written by Greg Matloff for this site, explains Greg’s previous work with holography and its ability to contain messages or images. But it goes on from there to the question of whether a sail could itself carry a holographic image that would make it more likely to be stable under the beam. Quoting:

“It no longer seems impossible to me that the Project Starshot goals can be achieved. One would use a holographic film and expose the image of a filter or mirror that is highly reflective in the laser’s wavelength range. My colleague at Citytech, Lufeng Leng teaches optics. She is quite sure that a hologram of a spherical surface will behave optically like a spherical surface. So the filter or mirror should ideally have a convex spherical shape, from the point of view of the observer (or laser).”

This is, as Greg explicitly says, a holographic image of a mirror that is highly reflective to the laser’s wavelength. It is not a holograph for messaging, but for propulsion.

Paul – Thank you very much for the information and clarification regarding any information packages on Breakthrough Starshot. Let us “worry” about such things perhaps whenever the probe is actually built. :^) Until then it is an important intellectual exercise for this concept.

AlexT – Since you enjoyed quoting me so much (aka, attempting to use my words against me), here is one more quote by me which sums up my thoughts and feelings on those who find the Golden Records somehow “shameful”:

“For someone like me, who has immersed himself for a lifetime moving about the worlds of science and the humanities/arts, it is hard to imagine how those who can dream of exploring the stars and all their unknowns – plus actually do something to make those dreams a reality – could simultaneously dismiss and even feel embarrassed and hostile to the idea of life elsewhere, including those capable of finding the probe and its shiny metal gift. However, as consulting producer Jeremy Lipworth said, this “says a lot about humanity,” which is the whole point for the existence of the Golden Record.”

Go watch the current news for five minutes, then let us talk about real shameful human actions.

All I know is the Voyager Interstellar Record and Pioneer Plaques have done much to interest many members of the public and stir debate about how we think about species who might otherwise never even considered space or supporting its science and exploration. And as Carl Sagan would tell you, half the reason those information packages were designed were for the benefit of its makers as much as anyone else in the Universe.

Paul, Yes , my fault, this doubtful (IMHO) plaque was designed and got funds in 2001 , as author wrote “my small NASA University Challenge Grant through Pace University, where I taught at the time, was reconfigured to support the creation of the hologram”.

But now – “On April 11, the Starshot advisors met at a Breakthrough facility in the NASA Ames Space Flight Center. While C displayed the prototype holographic message plaque”.

There is no free lunches…

And there is direct connection between plaque and Brealthrough Starshot, and reality is not so optimistic / altruistic.

I can only repeat: Starshot has absolutely no interest in a holographic ‘messaging’ plaque aboard its wafer spacecraft. Greg simply displayed the plaque as an example of holography. The question Greg introduced is whether holography could be used to optimize the sail’s interactions with the beam. This has nothing to do with messaging.

“Starshot has absolutely no interest in a holographic ‘messaging’ plaque aboard its wafer spacecraft” – thanks for clarification, my apologies for the false conclusions.

I was wrong and glad to discover that I was wrong.

The discussed article somehow make connection between two totally different objects that use common word – Hologram.

No problem, AlexT. Glad it’s straightened out.

They should and must put some kind of information package on Breakthrough Starshot. In fact I think it should be illegal not to do so for any deep space probe.

If an alien vessel came drifting through our Sol system and we were able to catch it, would not many if not all investigators be grateful for a deliberate message/information package from its makers? Not only for the invaluable knowledge but also to alleviate fears of any hostile intent.

I am guessing if an alien craft was aimed our way with hostile intent, they would not bother placing a greeting card aboard. One way an advanced ETI could take us out if they wanted to is to send an interstellar vessel moving at relativistic speeds to impact Earth. The kinetic energy alone from such a collision would effectively sterilize the surface of our planet.

ljk quote: “could simultaneously dismiss and even feel embarrassed and hostile to the idea of life elsewhere, including those capable of finding the probe and its shiny metal gift”.

No respect to “the Gold Records” does not mean automatically – deny extraterrestrial life. I believe there is lot life in the Universe, I believe that there should be intelligent life outside of our Solar system (but I do not exclude possibility that we are alone).

In same time till our communication possibilities limited by speed of light – we have no real chance for communication with ETI , i.e. no information exchange is possible with our present civilization/science level (communication is not allowed by modern physics and homo sapience life span).

As sequence to send the plaque or “the Golden Records” to the space has the same effect as simply throw it to the trash been, probability that it will be found by ETI (in space-time continuum) – is exactly same… only “space” plaque has higher price.

By the way you and me both are representing the same animal specie – homo sapience, but have obvious problems to understand one another, this is the good indication about our ability to communicate with intelligent species developed during alternative evolution flow… (even if communication with ETI could be easily possible).

Oh no, I understand you quite well. I simply do not agree with most of your viewpoints. Therefore, I see no need to acquiesce any more than you intend to conform to mine due to such

diametrically opposite thinking. I have stated my views in detail with verifiable examples multiple times, but it is clear that you are no fan of the Voyager Records and Pioneer Plaques (and apparently Carl Sagan as well) so see no need to accept the other side of this argument.

You seem to think that if we do not achieve communication with an ETI in a human lifetime based on their responding to any messages we send their way that this is a failure of the entire METI enterprise.

While it would of course be very nice to receive a reply from an ETI in our lifetimes, our sent messages can still be a success even if we never hear from them so long as they do receive our hails.

Of course, as has been pointed out by those in the SETI field, even a negative response can teach us something about what is and is not there in the galaxy.

Think of a library full of books written centuries ago. Those authors still speak to us and we receive value from their thoughts and ideas even though we can no longer speak back to them directly. No rational person would reject a library just because the authors are permanently unavailable for inquiry.

ljk quote: “…You seem to think that if we do not achieve communication with an ETI in a human lifetime … this is a failure of the entire METI …”

My arguments are not so simple as you represent is here, but common answer – yes.

Communication is impossible without feedback time delay that is significantly smaller that life span of the whole system, in this case system includes not only single person lifetime, but lifetime of whole human society etc. So I am sure that communication limited by speed of light with ETI located further than tenth of lightyears – is impossible.

ljk quote: ” in the SETI field, even a negative response can teach us something”.

This argument is very well know to me :-)

Wandering how someone can finally decide that long time SETI efforts have negative results ?

I am sure , this could be never concluded by SETI fans, Universe is huge and SETI has unlimited amount of time for searching – till the “end of the Universe”. So there will never be negative result. It is religious beliefs only.

ljk quote: “our sent messages can still be a success even if we never hear from them”.

Again , the similar question: How can you measure results of your message if you even do not have possibility to get feedback about results you deeds? Action-reaction-action – it is how our consciousness is working. Sorry, it too is religious beliefs only.

ljk quote: “Think of a library full of books” – yes I think about library – the best place to build such library – it is planet Earth. The Earth has many order higher probability to be found/detected by some ETI than miniature Voyager probe (Voyager will became silent undetectable asteroid after it’s electrical supply will dry)…

First off, do NOT pin any religious attributes, attitudes, or beliefs regarding SETI on me. I simply want to know if there is intelligent life out there. In lieu of access to relatively interstellar vessels at the moment, we need to try whatever reasonable methods we can for now until interstellar space missions happen.

If you have issues with the methods at hand, please feel free to let the SETI community know and provide whatever funds and resources you can to change things. Complaining and mocking are cheap.

No one has ever said that the Voyagers and Pioneers and New Horizons will ever be easy to find. Of course Earth is much easier to locate by comparison.

Their advantages over Earth are that they are moving out in different directions through the Milky Way galaxy.

Yes, yes, so is Earth and the Sol system over a long time, but they are moving as a single unit, whereas the space probes and their final rocket stages are spreading out. Small, yes, but spreading out in different directions just the same. And more will be joining them.

The other advantage the probes have is their longevity. You have no doubt heard that the exterior side of the Golden Records will last at least one billion years in deep space, and that is a conservative estimate.

Almost nothing on Earth made by humans will last nearly that long in any intact form. If we want to preserve our history and culture, space is a far better place to do so.

Yes it is problematic if ETI will ever find these probes. However, future humans will very likely know about them and if we become an interstellar species, they will likely want to find and study these relics from the early days of the Space Age. They might also appreciate finding deep space vessels which have preserved any and all records of humanity from the time period they were launched. That has value in and of itself.

For further reading:

https://centauri-dreams.org/2013/01/18/the-last-pictures-contemporary-pessimism-and-hope-for-the-future/

Will the pulsar map only confound ETI recipients of the Pioneer Plaques and Voyager Records as to where they came from in the Milky Way galaxy?

https://www.forbes.com/sites/startswithabang/2017/08/17/voyagers-cosmic-map-of-earths-location-is-hopelessly-wrong/#402550c869d5

For the details on that pulsar map:

http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/astro/pulsarmap.html

The 1972 paper on the Pioneer Plaque online here:

https://astro.swarthmore.edu/astro61_spring2014/papers/sagan_science_1972.pdf

Voyager, a Love Story…

https://science.nasa.gov/science-news/science-at-nasa/2011/28apr_voyager2/

Voyagers

A Short Film by Santiago Menghini

Travel along with Voyager spacecraft through their planetary expedition spanning over three decades.

Voyagers: Case Study

This film showcases the images and sounds of the solar system through the real photographs and plasma frequencies received by the Voyager crafts.

http://santiagomenghini.com/voyagers-film/

Uh oh…

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/official-description-aboriginal-music-voyager-121700198.html

An Excellent write up Lawrence Klaes I really enjoyed reading it and also following your post on social media, keep it up.

Now I just need to find the time to watch this along with Forbidden Planet!

Cheers Laintal

Thank you very much, Laintal. I enjoy your informative posts as well.

An interesting personal take on the Voyager Interstellar Record:

https://rosemetalpress.com/books/the-voyager-record/

When I first started reading this I thought; “Oh no, a millennial trying to interpret something from a time before his.” I especially felt this when he started saying the Golden Record team should have used different music – a complaint I have seen many times and one that is far too late to rectify anyway, unless you want to get your own selections aboard another satellite and launch it into deep space, which is more plausible and possible than ever now. Democracy in action via space travel.

Besides the fact that the author is of course entitled to his own opinions (though one should always prefer the informed kind), he did make some interesting and even useful observations. This included trying to view the Golden Record as an alien might, basing it on his feeling alienated as one in a foreign terrestrial land.

Azerbaijani Music Selected for Voyager Spacecraft

by Anne Kressler

Azerbaijan International

Summer 1994 (2.2), Pages 24-25

http://www.azer.com/aiweb/categories/magazine/22_folder/22_articles/22_extraterrestrial.html

Perhaps, it was because of the great constraints of time and budget and because Azerbaijan under the Soviet regime was so inaccessible to the Western world that very serious errors in the description of the music are included in the, otherwise, very excellent book, Murmurs of Earth: The Voyager Interstellar Record, by Carl Sagan and others (New York: Random House, 1978).