These days we take in data at such a clip that a mission like New Horizons will generate papers for decades. The same holds true for our burgeoning databanks of astronomical objects observed from the ground. So it only makes sense that we begin to recover older datasets, in this case the abundant imagery — photographs, radio maps, telescopic observations — collected in the pre-digital archives of scientific journals. The citizen science project goes by the name Astronomy Rewind, and it’s actively resurrecting older images for comparison with new data.

Launched in 2017, Astronomy Rewind originally classified scans in three categories: 1) single images with coordinate axes; 2) multiple images with such axes; and 3) single or multiple images without such axes. On October 9, the next phase of the project launched, in which visitors to the site can use available coordinate axes or other arrows, captions and rulers to work out the precise location of each image on the sky and fix its angular scale and orientation.

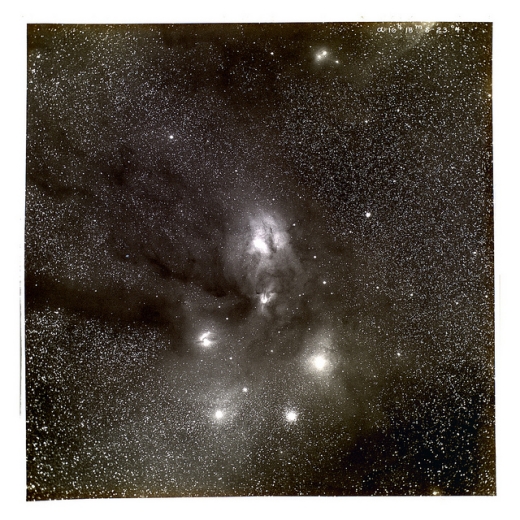

Image: Astronomer E. E. Barnard photographed the Rho Ophiuchi nebula near the border of Scorpius in 1905 through a 10-inch refractor. When he published the image in the Astrophysical Journal five years later, he discussed the possibility — then fiercely debated — that bright nebulae are partially transparent and dark nebulae are opaque, hiding material farther away. Other researchers argued that dark nebulae are simply regions where stars and gas are absent. Credit: American Astronomical Society, NASA/SAO Astrophysics Data System, and WorldWide Telescope.

We have over a century of images to work with, some 30,000 at present drawn from American Astronomical Society journals the Astronomical Journal (AJ), Astrophysical Journal (ApJ), ApJ Letters, and the ApJ Supplement Series. These images were provided through the Astrophysics Data System (ADS), which draws on NASA funding and provides bibliographical and archival services at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Laboratory (SAO), which is part of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

What’s next for the initial round of imagery is inclusion into the WorldWide Telescope. Originally a Microsoft project, the WWT is now managed by the American Astronomical Society, and serves as what the AAS calls a ‘virtual sky explorer that doubles as a portal to the peer-reviewed literature and to archival images from the world’s major observatories.’ 10,000 images (those with coordinate axes) are to be placed within the WWT within a few months, while volunteers proceed to identify where the remaining 20,000 images belong on the sky.

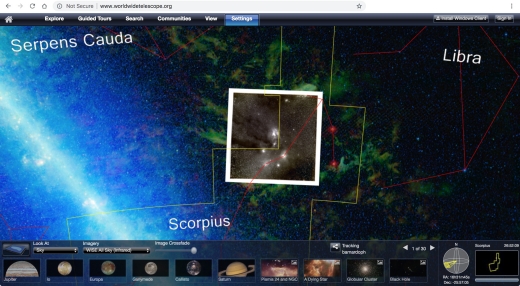

Image: Barnard’s photo has been placed on the sky in its proper position and orientation and is displayed in WorldWide Telescope (WWT) superimposed on a false-color background image from NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE). Credit: American Astronomical Society, NASA/SAO Astrophysics Data System, and WorldWide Telescope.

But these images are not the only ones arriving for inclusion into the growing database. Results from the related ADS All Sky Survey are also going into the WorldWide Telescope, along with a European image display tool called Aladin, developed at the Centre de Données astronomiques (CDS), Strasbourg Observatory, France. The software highlights the effectiveness of the concept, for with Aladin, users will be able to click on any image that originally appeared in one of the AAS journals and call up the corresponding research paper. Alyssa Goodman, one of the project’s leaders at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), comments:

“Without Astronomy Rewind, astronomers would be unlikely to make the effort to extract an image from an old article, place it on the sky, and find related images at other wavelengths for comparison. Once our revivified pictures are incorporated into WorldWide Telescope, which includes images and catalogs from across the electromagnetic spectrum, contextualization will take only seconds, making it easy to compare observations from a century ago with modern data to see how celestial objects have moved or changed.”

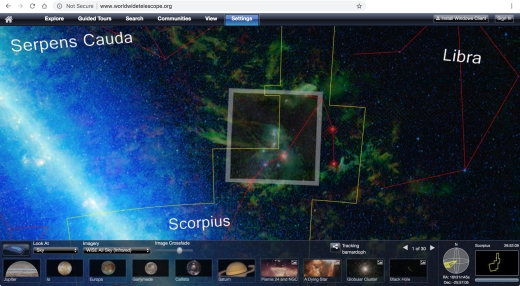

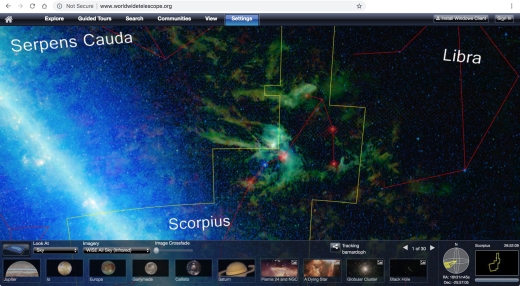

Image: In these two figures, Barnard’s photo has been made partially and fully transparent, respectively, to reveal it in context. In the visible-light photo, gas glows brightly while dust appears in silhouette. In infrared light, as seen by WISE, dust glows brightly where in visible light there was nothing but blackness. Barnard was right! Credit: American Astronomical Society, NASA/SAO Astrophysics Data System, and WorldWide Telescope. Credit: AAS.

As Centauri Dreams readers know, I’ve often enthused about the potential for citizen science projects both in terms of their effectiveness at identifying and cataloging astronomical phenomena as well as the opportunity they present for non-professionals to contribute to fields ranging from deep sky objects to exoplanets and our own Solar System. Astronomy Rewind is clearly keeping the momentum of such efforts going. As it moves into a more challenging phase of confirming the position, scale, and orientation of decades-old astronomical images, the project will offer help features run by astronomy graduate students.

Thus we revive work going back to the 19th Century and link to the work discussing it, with all journal images contextualized on the sky. That’s quite a goal, and it invariably reminds me of the debate over Boyajian’s Star (KIC 8462852, more familiarly known as Tabby’s Star), in which the question of long-term dimming was addressed by a study of 500,000 photographs in the archives of Harvard College Observatory, over a century’s worth of images being digitized through the Digital Access to a Sky Century@Harvard (DASCH) project.

Projects like these are massive in scope and their efforts constitute a heartening work in progress. Ultimately, every astronomical image available in any scientific journal or academic or observatory collection will be catalogued, giving us a way to study the sky over periods of time that are lengthy in comparison to a human lifetime but tiny at the astronomical scale. Nonetheless, KIC 8462852 showed us how an unexpected need to examine old data could propel a scientific debate and flesh out information about a newly discovered mystery.

As regards KIC 8462852, I understand there are some UK photographic plates in the USA, which contains images of this object, which are yet to be examined.

Talking of archive data, here’s a use of archive plates to investigate the ringed object in the J1407 system. Whatever’s going on there, it doesn’t seem to be as straightforward as it first appeared.

Excellent catch!

Might be easier to remember as “V1400 Centauri” per the paper you’ve linked to…?

I do hate to sound like a killjoy, but this endeavour does strike me as a great fit for the latest and greatest Artificial Intelligence systems using deep learning and neural nets, to automate the entire process.

OK – this obviously brings up a thorny group of questions. If we’re going to store all this information, which serves to preserve this data treasure trove, then I would presume that everybody’s onboard with the idea of retaining the original materials ?

Because the usual course of events is and the thought processes -are now these days-well, everything’s been converted over to a digital database so I guess we can scrap all the original materials…

And I really do think that this is becoming so commonplace that it’s almost secondary. But is that an actual good practice? Depending upon the level of reproducibility of the digitized data you may or may not retain important pieces of information. But people are so quick to throw away originals that in one sense, no storage is actually occurring at all. So, since Mr. Gilster wrote this, then the obvious question is, does he know whether or not photographic plates, old computer tapes, paper documents, etc. etc. etc.-are they in fact, retained?

And it seems Mr. Gilster that it now incumbent upon you to write a follow-up article concerning the level of accuracy that is obtained in the raw data. Don’t you think that’s correct?

Such an article would certainly be a good idea, though at the moment it’s too early in the process to write it — let’s get some of these databases filled out and then see where we are.

So, Mr. Gilster , does photographic plates, old computer tapes, paper documents, etc. etc. etc.-are they in fact, retained?

That was a ques. ???

I don’t know about computer tapes, but I believe any competent observatory staff would save all such materials, certainly plates and documents, going a long way back.

Charley, you can always contact the relevant observatories to ask them directly, then report back here.

ljk, “you can always contact the relevant observatories to ask them directly, then report back here.”

I could , but I’m not significant …

First of all, please never say that about yourself.

Secondly, you do not need to be some professional astronomer to get such information. You and just about anyone else have every right to contact them to find out what is going on.

From my experience these folks are happy to talk about their work because relatively few in the public ask about it. Or if the public does engage them the conversations almost invariably slip to the subject of UFOs and such.

And if one observatory is not obliging, there are plenty of others to contact. Good luck!

OK … but Mr. Gilster is significant (and famous)- and the observatories WOULD respect that more …

You overestimate me by orders of magnitude, my friend. I’m neither significant nor famous, but certainly enjoying tracking the deep space news! As for tracking down retention policies at multiple astronomical sites, I’d love to do it but simply lack the time.

Looking into the works of the yore is yet another way of climbing onto the shoulders of bygone giants. And with it the possible recognition that may be awarded to crowd-sourced citizen science: it would still take a fair measure of gestalt and intuition to correctly decide which incongruous findings should be pursued: had Cosmic Mirrowave Background radiation been written off to pigeon droppings, a Nobel might have not gone to the phone company Labs’ engineers.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1811.02265

VVV-WIT-07: another Boyajian’s star or a Mamajek’s object?

Roberto K. Saito, Dante Minniti, Valentin D. Ivanov, Márcio Catelan, Felipe Gran, Raymundo Baptista, Rodolfo Angeloni, Claudio Caceres, Juan Carlos Beamin

(Submitted on 6 Nov 2018)

We report the discovery of VVV-WIT-07, an unique and intriguing variable source presenting a sequence of recurrent dips with a likely deep eclipse in July 2012. The object was found serendipitously in the near-IR data obtained by the VISTA Variables in the Vía Láctea (VVV) ESO Public Survey.

Our analysis is based on VVV variability, multicolor, and proper motion (PM) data. Complementary data from the VVV eXtended survey (VVVX) as well as archive data and spectroscopic follow-up observations aided in the analysis and interpretation of VVV-WIT-07.

A search for periodicity in the VVV Ks-band light curve of VVV-WIT-07 results in two tentative periods at P~322 days and P~170 days. Colors and PM are consistent either with a reddened MS star or a pre-MS star in the foreground disk. The near-IR spectra of VVV-WIT-07 appear featureless, having no prominent lines in emission or absorption.

Features found in the light curve of VVV-WIT-07 are similar to those seen in J1407 (Mamajek’s object), a pre-MS K5 dwarf with a ring system eclipsing the star or, alternatively, to KIC 8462852 (Boyajian’s star), an F3 IV/V star showing irregular and aperiodic dips in its light curve.

Alternative scenarios, none of which is fully consistent with the available data, are also briefly discussed, including a young stellar object, a T Tauri star surrounded by clumpy dust structure, a main sequence star eclipsed by a nearby extended object, a self-eclipsing R CrB variable star, and even a long-period, high-inclination X-ray binary.

Comments: 7 pages, 5 figures. Accepted for publication in MNRAS

Subjects: Solar and Stellar Astrophysics (astro-ph.SR)

Cite as: arXiv:1811.02265 [astro-ph.SR]

(or arXiv:1811.02265v1 [astro-ph.SR] for this version)

Submission history

From: Roberto Saito [view email]

[v1] Tue, 6 Nov 2018 10:06:38 UTC (3,968 KB)

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1811.02265.pdf