It seems to be a week for endings. Following the retirement of the wildly successful Kepler spacecraft, we now say goodbye to Dawn following an extraordinary eleven years that took us not only to orbital operations around Vesta but then on to detailed exploration of Ceres. The spacecraft ran out of hydrazine, with the signal being lost by the Deep Space Network during a tracking pass on Wednesday. No hydrazine means no spacecraft pointing, vital in keeping Dawn’s antenna properly trained on a distant Earth.

I immediately checked to see if mission director and chief engineer Marc Rayman had gotten off a post on his Dawn Journal site, but he really hasn’t had time to yet. It will be interesting to see what Dr. Rayman says, and it’s appropriate here to thank him for the continuing updates and insights he provided throughout the Dawn mission. Keeping space exploration in front of the public is essential for continuing funding of deep space robotic missions, as both the Dawn and New Horizons team clearly understand (and there is much ahead for New Horizons!)

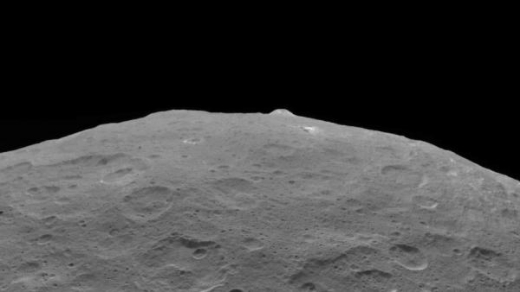

Image: This photo of Ceres and one of its key landmarks, Ahuna Mons, was one of the last views Dawn transmitted before it completed its mission. This view, which faces south, was captured on Sept. 1 at an altitude of 3570 kilometers as the spacecraft was ascending in its elliptical orbit. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA/MPS/DLR/IDA.

The ability to orbit one target, move on to another and subsequently establish an orbit there is a demonstration of what ion engines can do, and a reminder of how significant the Deep Space 1 mission was in terms of testing these technologies. If DS1 established ion propulsion as a viable tool, Dawn took it to the next level, highlighting the kinds of exploration that may lie ahead as we contemplate missions to multiple Kuiper Belt objects (see Game-changer: A Pluto Orbiter and Beyond). Ambitious missions grow out of the gentle, efficient thrust of ion engines.

Ponder this: The orbiters we’ve sent to Mars had to burn their engines for orbital insertion. Consider something on the order of 300 kilograms of propellant for conventional rocketry to meet this requirement. Dawn could make the same change in speed (about 1000 meters/second) using fewer than 30 kilograms of xenon. But of course we wouldn’t use ion engines for this purpose. Ion engines demand patience: It would take Dawn three months to achieve this result while conventional engines in our orbiters complete this maneuver in 25 minutes. But missions with multiple targets or complex operations in deep space are suited to engines like Dawn’s, which accumulated 2,141 days (5.9 years) of thrust time in the course of its travels.

Describing Dawn’s changing trajectories and the intricate gravitational dance they involved, Rayman wrote this paean to ion propulsion in his Dawn Journal:

Without that technology, NASA’s Discovery Program would not have been able to afford a mission to explore the exotic world in such detail. Dawn has long since gone well beyond that. Having discovered so many of Vesta’s secrets, the adventurer left it behind. No other spacecraft has ever escaped from orbit around one distant solar system object to travel to and orbit still another extraterrestrial destination. From 2012 to 2015, the stalwart craft reshaped and tilted its orbit even more so that now it is identical to Ceres’. Once again, that was essential to accomplishing the intricate celestial choreography in which the behemoth reached out with its gravity and tenderly took hold of the spacecraft. They have been performing an elegant pas de deux ever since.

And now the mission is over, though the spacecraft will remain in Ceres orbit for at least twenty years, and mission engineers believe with 99 percent confidence that its orbit will last at least 50 years, keeping planetary protection protocols in place for the near future. As we look back, consider Dawn’s accomplishments. It was the first spacecraft to orbit a body between Mars and Jupiter, the first to visit a dwarf planet and the first to orbit two destinations beyond Earth.

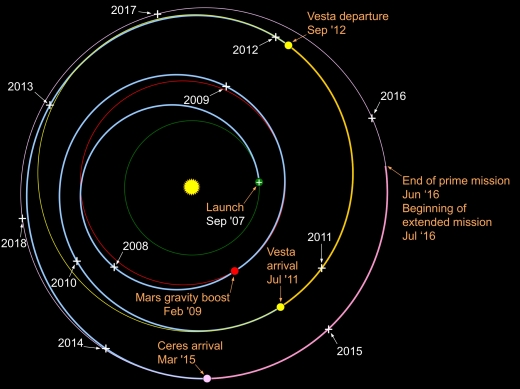

Image: Dawn’s interplanetary trajectory (in blue). The dates in white show Dawn’s location every Sept. 27, starting on Earth in 2007. Note that Earth returns to the same location, taking one year to complete each revolution around the Sun. When Dawn is farther from the Sun, it orbits more slowly, so the distance from one Sept. 27 to the next is shorter. Credit: NASA/JPL.

“In many ways, Dawn’s legacy is just beginning,” said principal investigator Carol Raymond at JPL. “Dawn’s data sets will be deeply mined by scientists working on how planets grow and differentiate, and when and where life could have formed in our solar system. Ceres and Vesta are important to the study of distant planetary systems, too, as they provide a glimpse of the conditions that may exist around young stars.”

Dawn’s discoveries at Vesta and Ceres have been described before in these pages, but we’ll track new conclusions from Dawn’s datasets well into the future. For now, I’m simply thinking about Dawn’s beginnings and all that has happened since. Congratulations to the entire team.

Image: Dawn climbs to space on Sept. 27, 2007, from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Dawn launched at dawn (7:34 am EDT). Credit: KSC/NASA.

When spacecraft die

Two NASA spacecraft are in the final days of operations as they run out of fuel, while a rover on Mars remains silent nearly five months after a dust storm swept across the planet. Jeff Foust reports on the impending demise of Dawn and Kepler and the last-ditch efforts to restore contact with Opportunity.

Monday, October 29, 2018

http://thespacereview.com/article/3595/1

Opportunity still has not contacted Earth…

http://www.spaceflightinsider.com/editorial/inside-opportunity-oppy-still-silent/

Should Opportunity have been equipped with the equivalent of a feather duster? … for want of a feather duster the opportunity was lost …

That was discussed before the MERs were even launched in 2003. The mission team decided that it was just one more part that could break down and consume energy better spent on the scientific instruments and vital engineering parts.

This is why they only gave the twin rovers a conservative warranty of 90 operational days on the Red Planet. PI Steve Squyres told me personally that they only expected the rovers to last 120 to 150 days, tops. That would still be enough time to use them to learn if Mars once had water, which both rovers did – in Opportunity’s case, it was almost immediate as the rover landed smack-dab in the middle of a crater with walls of hematite!

As luck would have it, nature provided the “feather duster” in the form of dust devils that periodically swept over the rovers and cleaned off the solar panels, sometimes almost as good as the day they had landed on the planet.

In terms of science and planetary exploration engineering, both MERs more than gave us our money’s worth, with every extra day being a bonus. So while it is sad that Opportunity may not recover, we already have the more advanced (and nuclear-powered) Curiosity operating on Mars, with InSight on its way and at least one more rover to depart Earth in 2020.

“Ponder this: The orbiters we’ve sent to Mars had to burn their engines for orbital insertion.”

Nope. Mars Global Surveyor, Mars Odyssey, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and Exomars TGO used aerobraking for orbit insertion.

Actually, Mars Odyssey used a main engine firing for deceleration and then used aerobraking to circularize its orbit. MRO used a main engine burn of 27 minutes, using aerobraking to achieve a lower, circular orbit. ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter used both aerobraking and thruster firings to circularize its orbit. So aerobraking was indeed a part — but not the entirety — of these maneuvers.

I was a big fan of DS1 and very pleased to see the technology moving forward with Dawn. It certainly hasn’t disappointed.

I read Raymans DAWN Journal regularly and remember the entry from September 2014 particularly well.

“There is no intention to fly to a lower orbit. Even if the two remaining reaction wheels operate, hydrazine will be running very low, so time will be short. Following another spiral to a different altitude would not be wise. There will be no below-LAMO (BLAMO) or super low altitude mapping orbit (SLAMO) phase of the mission.

There is another issue as well. As we will describe in December, there is good reason to believe Ceres has a substantial inventory of water, mostly as ice but perhaps some as liquid.The distant sun and the gradual decay of radioactive elements provide a little warmth. Telescopic studies suggest the probable presence of organic chemicals. As a result of these and other considerations, scientists recognize that Ceres might display “prebiotic chemistry,” or the ingredients and conditions that, on your planet, led to the origin of life. This could present important clues to help advance our understanding of how life can arise.

We want to protect that special environment from contamination by the great variety of terrestrial materials in the spacecraft. As responsible citizens of the solar system, NASA conforms to “planetary protection” protocols which specify that Dawn may not reach the surface for at least 50 years after arrival. (The reasoning behind the limited duration is that if our data indicate that Ceres really does need special protection, half a century would be long enough to mount another mission if need be.) Extensive analyses by engineers and scientists show that for any credible detail of the dwarf planet’s gravitational field, the orbit will remain relatively stable for much longer than that, perhaps even millennia. The ship will not make landfall.”

How things change. The stringent minimum of at least 50 years of planetary protection was quietly dropped.

Now 20 years has been deemed sufficient.

Quoting from yesterdays New York Times article on DAWNs demise and NASAs thinking on the new chosen 20 year “protective phase”:

“That is not long enough for all of the Earth microbes on Dawn to die, but NASA officials hope that 20 years would be long enough for the space agency to make another visit there to study whether Ceres ever had conditions amenable for life before Dawn crashes and contaminates it.”

I hope I am not the only one who finds this attitude reprehensible.

This is what NASA was hoping for Mariner 9 in 1972. The first successful Mars orbiter was left in an orbit that would last for fifty years, or 2022. No doubt they thought back then that someone would recover the space probe before it impacted on the Red Planet, but that seems quite doubtful now.

Of course we have other defunct robot vessels circling Mars, including the Soviet probes Mars 2 and 3 – how long are they expected to stay up there, and how decontaminated were they? They also placed two landers on the surface: Mars 2 crashed and Mars 3 worked, but only for a very brief time. How well did the Soviets do removing any microbes on them?

We may have to accept that we cannot explore the Sol system and beyond without some level of disruption and contamination. Certainly we can reduce the number of tiny “fellow travelers”, but in the end we will have to hope they will not manage to colonize other worlds on their own.

Actually, we have only a vague idea how long it will take Earth microbes to die off on a trip like Dawn’s. Dawn has already been in space for 11 years. Another 20 years will extend that to 31. Any microbe on it will have been subjected to 31 years of vacuum, UV, hard radiation, desiccation, and spectacular extremes of heat and cold. Yes, there are spores and extremophiles that can survive one or two of those things for long periods of time. All of them together? For 31 years? That’s firmly not proven.

Yes, we’ve found bacterial remains in swabs of the hull of the ISS. We have no idea how old those were — current thinking is that they come from inside the ISS when the airlocks were opened — and also the hull of the ISS is a significantly less challenging environment than the surface of a probe in deep space. And, of course, Dawn’s microbial load was probably pretty tiny to begin with, because it was under planetary protection procedures during construction and launch.

Finally, any hypothetical microbe would have to be able to survive on Ceres’ surface, which is a mixture of bare rock and salty, very cold ice, in a heavily irradiated vacuum, with temperatures (on the equator) that cycle between -40 C and -150 C every few hours. If you know of an extremophile that’s shown the ability to reproduce under those circumstances, please tell me! I’ll be interested to hear about it.

TLDR: in this context, I suspect “not long enough” is probably shorthand for “not long enough to reach what most professionals would accept as five sigmas of certainty”.

Doug M.

Outstanding work by this probe: Not only exploration, but flight

dynamics testing of ION propulsion tech.

Was there not a target nearby to gently lay this craft down and get a close up view. it’s Ion Engine probably had enough thrust to gently land on a 2-3 mile body there.

I guess it would have taken too much fuel to exit the orbit of

Ceres, as feeble as it gravity is. But this could have been planned out.

We know so little about the lesser objects in the Belt, are they more rocky than Icy, if Icy does the ice have the same “creme brulee” consistency of the comet that Rosseta sent it’s lander too 67p. Or has the closer orbit of the sun modified the ices in other ways.

I know every thing is a trade off, And If this was considered and rejected by NASA the my hats off to them for working the idea at least.

J’ai embrassé l’aube d’été.

Rien ne bougeait encore au front des palais. L’eau était morte. Les camps d’ombres ne quittaient pas la route du bois. J’ai marché, réveillant les haleines vives et tièdes, et les pierreries regardèrent, et les ailes se levèrent sans bruit.

La première entreprise fut, dans le sentier déjà empli de frais et blêmes éclats, une fleur qui me dit son nom.

Je ris au wasserfall blond qui s’échevela à travers les sapins : à la cime argentée je reconnus la déesse.

Alors, je levai un à un les voiles. Dans l’allée, en agitant les bras. Par la plaine, où je l’ai dénoncée au coq. A la grand’ville elle fuyait parmi les clochers et les dômes, et courant comme un mendiant sur les quais de marbre, je la chassais.

En haut de la route, près d’un bois de lauriers, je l’ai entourée avec ses voiles amassés, et j’ai senti un peu son immense corps. L’aube et l’enfant tombèrent au bas du bois.

Au réveil il était midi.

– Aube (“Dawn”), Jean-Nicolas-Arthur Rimbaud, sometime in the 1870’s

– – – – –

I have embraced the summer dawn.

Nothing yet stirred on the fronts of the palaces. The water was dead. Swarms of shadows still camped on the road to the wood. I walked along, awakening the warm, alive air. Stones looked up, and wings rose up without a sound.

The first occurrence, in a path already filled with fresh, pale gleams, was a flower which told me its name.

I laughed at the blond waterfall which tumbled down through the pine trees: at its silver summit I recognized the goddess.

Then I lifted her veils, one by one. In the path, where I waved my arms. Across the field, where I announced her name to the cock. In the city, she fled among the steeples and domes; and running like a thief among the marble quays, I chased her.

Above the road, near a laurel wood, I wrapped her in all her veils and felt something of the immensity of her body. Dawn and the child collapsed at the edge of the wood.

Upon awakening, it was midday.

– a melding of Wallace Fowlie’s translation in W. Fowlie, Rimbaud: Complete Works, Selected Letters, at 215 (University of Chicago Press, 1966), and the one on this website: http://www.mag4.net/Rimbaud/poesies/Dawn.html , which I believe was by the young lady who created the site

– – – – –

Rimbaud’s imagery of chasing the dawn breaking across the French countryside also perhaps reflects here the lifting of the veils of Nature through discovery, one by one, and the continually fleeting nature of that experience, as we, each time, sense only “un peu son immense corps.”

Magnifique moment de poésie, excellente et inattendue façon de terminer cette belle journée d’été indien ici en France. Merci !

One theme that emerges for me with the Dawn mission, is how “ground truth” banishes speculation about aliens. We have the light curve data from Tabby’s star that still results in speculation about partial Dyson swarms. ‘Oumuamua’s path through Sol with light curve data, the possible acceleration due to other causes that outgassing led to all sorts of Rama-like speculation. Ceres initially showed bright spots in low resolution and high contrast, that resulted in speculation about alien bases on that world. Unlike the previous examples, Dawn was able to make a close reconnoiter via many orbits that revealed the bright spots to be probably salt deposits. The specter of aliens disappeared and the world was once again a purely natural object.

While the sample is very small, it does suggest to me that it is necessary to exclude resorting to agency before all natural explanations are proven wrong. That might leave us in a “we don’t have enough data to know” situation, but we should resist the temptation to find aliens where probably none exist. I suspect the aliens (agency) explanation is the modern equivalent of animism, panpsychism, even polytheism.

and if a probe goes missing in the asteroid belt what could be the

cause

A) could it be space worms

Or

B) terminal malfunction

Or

C) Communication failure

But some minds need a supernatural explanation, so we are

not so removed from shaman/witchdoctor/mystics predating

the dawn of civilization.

Yes, but how much less would our culture be without the Canals of Mars and its presumed builders. It was a “romantic” time when some thought that the Red Planet was inhabited and not without good reason.

Note how disappointed many were when Mariner 4 revealed a “dead” Mars covered only with craters and dust to the point that we are still not ready to send humans there. The same thing happened to a lesser extent when Mariner 2 revealed a Venus that was a roasting unlivable desert rather than a lush jungle populated with dinosaurs or at least a global sea of seltzer or maybe even oil.

The prehistoric Venus and the ancient Martians of Bradbury’s elegiac stories are great fiction, but reality is more important to me. We hold so many fantasies about the world, yet science shining a light and discovering truths is far more interesting than sticking with the fantasies. That is the culture I want to live in.

Me too, but they can serve as great inspiration. And I would love to say it is science that most motivates the funders to explore space, but it seldom is even today.

Son immense corps? De “Dawn”? Tu exagères mon cher!

Marc Rayman • December 21, 2018

Dawn Journal: Final Transmission

Following a successful mission, Dawn mission operations concluded successfully on Oct. 31. (Please note the understated elegance of that sentence.)

After more than 11 years in deep space, after unveiling the two largest uncharted worlds in the inner solar system, after overcoming myriad daunting obstacles, Dawn’s interplanetary adventure came to an end.

We explained in detail in the two August Dawn Journals that the spaceship would deplete its supply of hydrazine, which was essential for controlling its orientation as it orbited dwarf planet Ceres. We predicted that the last of the hydrazine would be spent between mid-September and mid-October (although we acknowledged that it could be earlier or later). Dawn, ever the overachiever, held on until the end of October, and the explorer was productive to the very end. This was the best way to end a mission. It was good to the last drop!

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/marc-rayman/dawn-journal-final-transmission.html