As the exoplanet hunt deepens, we’re seeing how research efforts build upon each other, and how the findings of one investigation play into the planning for another. Kepler candidate planets, for example, have been confirmed using ground-based telescopes in radial velocity investigations, giving an independent check that the putative world is really there. TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) will find planets that refine the target list for the James Webb Space Telescope, with extremely large telescope technology already in the wings.

What we sometimes forget is that this collaborative effort has already built up a healthy momentum. Having maxed out Kepler (and K2 was an outstanding rehabilitation of a damaged spacecraft), the operations of TESS will focus on bright, nearby stars. The momentum of TESS and its contributions to the upcoming JWST should remind us that we then have the European Space Agency’s CHEOPS (CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite) mission queuing up for launch.

ESA has just announced 15 October to 14 November of 2019 as the launch window for CHEOPS, whose ancient name bears parallels to NASA’s Lucy mission. Whereas the inspiration for Lucy was a four-million year old ancestor of modern humans who lived in what is now Ethiopia, CHEOPS bears the name of an ancient Egyptian monarch named Khufu — he was known to the Greeks as Cheops — who lived in the Old Kingdom period in the 26th Century BC, and who may well have commissioned the Great Pyramid of Giza.

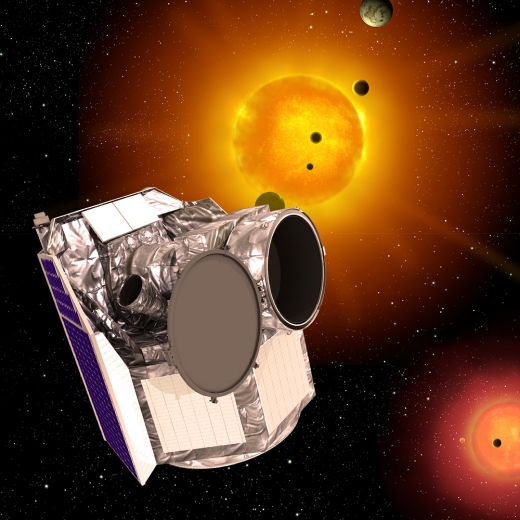

The link to ancient humanity, whether intentional in the case of the CHEOPS acronym or not, is a fitting perspective enhancer for a mission that involves expanding our understanding of our place in the universe. The purpose of the mission is to provide precise radius information for exoplanets that have been identified by earlier missions like TESS, using a 30 cm optical telescope working in a Sun-synchronous orbit about 800 kilometers above the Earth. CHEOPS will also target exoplanets found by radial velocity methods and larger worlds found in ground-based transit work.

Image: Artist’s impression of CHEOPS. Credit: ESA – C. Carreau

Tightening up our radius estimates of known exoplanets by observing multiple transits of each planet will help to establish the density of these worlds by comparison with mass estimates provided by radial velocity studies. We wind up with constraints on their composition, with the focus on planets ranging from super-Earths to Neptune-class. Out of all this will surely come candidates for follow-up spectroscopic analysis by the instrumentation that will follow.

Having just completed its environmental test campaign at ESA’s technical centre in the Netherlands, CHEOPS is currently at Airbus Defence and Space in Spain for final testing before being declared fit for its 2019 launch. With this in mind, we also look forward to ESA’s PLAnetary Transits and Oscillations of stars (PLATO) mission, whose planned transit work will target one million stars, emphasizing rocky planets in the habitable zone. With launch scheduled for 2026, PLATO is to be followed by ARIEL (Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey), which will survey the chemistry of roughly 1,000 exoplanet atmospheres.

Those of us whose memories of Apollo are vivid sometimes despair when we see the slow pace of human space exploration in the decades since, but we do see momentum building in the exoplanet realm as developing technologies portend serious breakthroughs ahead. A great age of discovery is upon us even if finding approval for the needed resources isn’t always easy. How the exoplanet revolution unfolds will shape our understanding of our place in the cosmos.

Just wondering, it seems that all of these upcoming missions are focused on the relatively small set of systems that have transiting planets. Granted, we’ll be able to find out much more about such planets due to fortunate orbital alignment, but what about the majority of systems that don’t have transits? Are there missions in the works that will help cover the vast non-transit set of exoplanetary systems?

Bruce, here’s a paper with an interesting take on this question:

https://arxiv.org/abs/1708.05560

Titled “Future Astrometric Space Missions for Exoplanet Science,” it looks at using astrometry to tease out the tiny variations in a star’s motion that indicate the presence of planets — a different method entirely from radial velocity. One interesting mission is THEIA, “…a single-unit telescope designed for both dark matter studies as well as a survey for habitable Earth-like planets among the 50 nearest stars.” More on this in the near future.

Thanks for that reply. Yes, it was an interesting article, and nice to learn about astrometry as another coming tool in the exoplanet search toolkit.

Of the two main planet hunting methods only transit detections are clearly better off done from outer space. There will be a white paper proposal for the next decadal arguing for a radial velocity space mission called EarthFinder, but this is the exception the proves the rule.

https://arxiv.org/abs/1803.03960

It is generally simpler and cheaper to do it from the ground, so the next radial velocity “missions” after the likes of ESPRESSO will be spectropgraphs on the ELT and the TMT.

As for the other types of mission;

Astrometry doesn’t appear to have gotten much love of late. I guess when you are competing with missions that can offer more in-depth information like transit-based science can it’s a tougher sell. For example in the beginning the THEIA proposal mentioned above started off emphasising exoplanet science but after PLATO, CHEOPS and ARIEL got selected they changed tack to focus on dark matter. Perhaps things might change when the Gaia planetary results are released.

The first breakthroughs in direct imaging of small planets are again probably going to come from the next generation ground based telescopes or WFIRST as the community STILL seems unable to come up with a unified space-based architecture that will satisfy most.

It looks like CHEOPS will have its work cut out for it if it is assigned to determine the radii of planets detected based on Doppler velocity measurements. Unless they transit or have been sighted already in higher plane orbits, I don’t see how otherwise.

Then there is the problem of detecting an exoplanet atmosphere:

Amid all the other details coming in about exoplanets from Kepler, for example, hardly had time to think about the mechanics of this next phase. Maybe someone will provide some more background.

Looking back, Kepler’s method seemed simple in principle, but requiring big data from CCDs of large size to explain every pixel dip in a field of stars.

It would seem that one way PLATO or other atmospheric detection telescopes would be working with pre or post transit exoplanets – so beside having a lock on the star center with perhaps a blotting disc, there would be need for either a wide or narrow aperture device to acquire the planetary light source and do either a digital or diffraction based spectral analysis of reflected stellar light. By any measure this will be close to the star, which could be the entire orbit, probably some sort of background glare, perhaps from equivalent of zodiacal dust. Depending on the stellar type (O,B,A, F,G.K,M…), there will be variation in the relative brightness of a “habitable” zone planet… Have to wonder what the so-called low hanging fruit will be this time other than uninhabitable worlds irradiated from without or due to internal ( greenhouse or convective updraft) heating. And then if the previous report about the Trappist 1 planets is accurately predictive (hot), then maybe one or two of their atmospheres will be within near term detectability.

What’s most encouraging about this whole problem is that investigators and observatories are beginning to take it on.

The U.S. needs to get the next exoplanet mission WFIRST on track and funded with the exoplanet imaging coronagraph instrument included. Look how successful Hubble has been and WFIRST could be capable of similar feats and length of operation. Write your congressman!

Senator Seeks Assurances on JWST and WFIRST Funding.

November 27, 2018

https://www.space.com/42555-senator-seeks-assurances-jwst-wfirst-funding.html

NASA Weighs Delaying WFIRST to Fund JWST Overrun.

https://www.space.com/41292-nasa-weighs-delaying-wfirst-jwst-overrun.html

It seams that “AAVSO Exoplanet Archive” moving in some opposite direction of this article… :-)

Don’t forget WFIRST, which has a 99% chance of confirming the Bernard’s Star b planet via astrometry, should it exist.

Excellent article. It does seem we are fortunate to be alive at this unique time. Within a few decades we will have found thousands (or even hopefully tens of thousands) of exoplanets circling other stars. At some point we may find clear signs of some form of life around one or more of them. That would be one of the high points of my life. I’m also continuing to watch the series “Mars” with some sadness as it appears those days when we walk on another planet are still quite distant. Who knows though if Elon Musk continues to move ahead with his space program. What an astounding pace he has set. NASA should be embarrassed enough to try and match him.

These people – NASA Moon/Mars initiative officials and Spacex BFS insiders should spend some time talking together. The situation is unusual.

First light for SPECULOOS.

Science operations will begin sometime in January 2019. This leaces several weeks for calibration tests, if any are needed. If they are needed, I hope they choose TRAPPIST-1 as their calibration star, because; if they are lucky, they may see another transit possible(only, for now)Mars sized planet with an orbital period far greater than that of TRAPPIST-1h.

TESS data on Planet Candidates, 164 listed 2 our in the habitable zone but both sub Neptunes.

https://exofop.ipac.caltech.edu/tess/view_toi.php?toi=&page1=1&ipp1=500&sort=planetnum

One of the ones in the habitable zone is closer to a Sub Jupiter in size and there is one listed (12421862) at 325K or about 125F, that is only 1.56 the size of Earth. All three have early M dwarf to late K dwarf mass and temperatures for the primary star.

How to Find Exoplanets and ‘Listen’ to Their Stars with TESS

By Astrobites on 19 February 2019

Title: A HOT SATURN ORBITING AN OSCILLATING LATE SUBGIANT DISCOVERED BY TESS

Author: Daniel Huber, William J Chaplin et al.

First Author’s Institution: Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai’i

Status: Submitted to AAS Journals

NASA’s space mission TESS is currently hunting for new exoplanets in the southern hemisphere sky. But while its primary aim is to find 50 small (radii less than 4 Earth radii) planets with measurable mass, there is a lot of other interesting science to do.

Today’s paper presents the discovery of a new exoplanet that is quite precisely characterised thanks to the complementary technique of asteroseismology used on the same data.

https://aasnova.org/2019/02/19/how-to-find-exoplanets-and-listen-to-their-stars-with-tess/