The exuberance of images like the one below captures the drama of Solar System exploration. Scenes like this are emblematic of the early reconnaissance of the Solar System. We saw similar enthusiasm with missions near and far — I’m thinking back, for example, not just to Voyager, but the Viking landings on Mars, and I’m sure Russian controllers were equally jubilant when their Venera craft touched down on Venus. Space is indeed the ‘final frontier,’ as James T. Kirk reminded us on Star Trek, and it’s a frontier that goes on without end.

Image: Celebration in full swing as scientists react to the view from New Horizons after the Ultima Thule flyby. Credit: NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI / Henry Throop.

Let’s keep in mind, then, that New Horizons is not just returning Ultima Thule data, but continuing to push into the Kuiper Belt doing good science. In terms of future missions, we need to learn as much as we can about radiation, gas and dust as we assess the environment. New Horizons will get an extended mission, we can hope with some justification, because after all, a fully operational spacecraft operating in this far region is a unique, invaluable resource.

But we don’t have to wait for an extension to continue exploring Kuiper Belt objects, even if no flyby is possible. I’m thinking of one called 2014 PN70, which will be observed in March. As mission principal investigator Alan Sterne notes in this latest report, this KBO was a proposed flyby target before Ultima Thule was chosen, losing out at least partly because it required more fuel to reach than Ultima.

Although the spacecraft won’t be able to see it up close, we should still be able to assess 2014 PN70’s shape, surface properties and rotation rate, as well as look for possible satellites. Discovered in Hubble observations, the object is known to be about 40 kilometers in diameter. New Horizons will be unable to resolve 2014 PN70 or another early flyby candidate, 2014 OS393, but study of both will help put the accumulating Ultima Thule data in perspective.

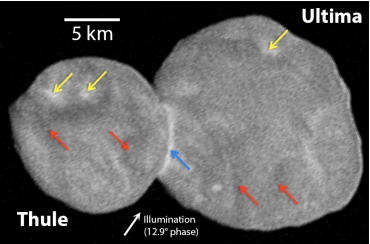

Image: Ultima Thule as seen in color by New Horizons during its close approach. Credit: NASA/JHUAPL/SwRI/Roman Tkachenko.

Recovering the entirety of New Horizons data on Ultima Thule will take 20 months, and recall that from January 4 to 9, controllers had to wait because the spacecraft was obscured by the solar corona, making communications problematic. At this point, the team has just 1 percent of all the Ultima Thule data. Hundreds of images and spectra remain to be downloaded, but the process of compiling science results is already well underway, with 40 abstracts submitted to the 50th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, to be held in Houston this March.

What a primitive place Ultima turns out to be, a fact which comes as no surprise. In the abstract for his talk in Houston, Stern summarizes its nature this way:

New Horizons has revealed MU69 to be a bi-lobate contact binary that appears to have merged at low speed. In addition to being the most primitive solar system object ever to be explored in situ by any spacecraft, MU69 thus also becomes the first primordial contact binary. The appearance and contact binary nature of this object is consistent with it being a relic planetesimal possibly created by pebble accretion. How MU69’s two lobes merged, how gently, and how much angular momentum was lost prior to contact are puzzles to be solved as more data are returned and detailed modeling can be undertaken.

Ultima Thule, then, as well as other Kuiper Belt objects we’ll study with New Horizons and later missions, becomes a key to the formation era of the Solar System, offering potential insights into planetary accretion. The available data have revealed no evidence of rings, a moon or an atmosphere, though we have to hold on that point until the dataset is complete. Differences in surface reflectivity are clear, including the striking brightness of the connecting ‘neck’ between the two lobes (the larger of which is now nicknamed Ultima, the smaller Thule).

Image: This is Figure 1 from Stern’s abstract. Caption: Ultima Thule as seen by the LORRI imager in the close approach CA04 observation (140 m/pixel), including relatively bright circular patches a few km wide (yellow arrows), darker regions up to several km wide (red arrows), a bright, cylindrically symmetric neck (blue arrow), and quasi-linear and arcuate bright features; note also the mottled appearance. Credit: JHU/APL; Alan Stern.

On the matter of dust, this is interesting:

Regarding dust near Ultima Thule, New Horizons saw no evidence down to I/F~5×10-7 in imaging available by 4 Jan 2019. In addition, zero impacts onto the New Horizons dust counter were detected inside MU69’s Hill sphere. And no satellites were detected down to 1.5 km diameter (under the assumption of an Ultima Thule-like reflectivity) outside of 1000 km from Ultima Thule. A search for closer rings or satellites has not yet been performed.

If New Horizons gets that extended mission, it should begin in late 2021. The good news that Stern passes along in his PI’s Perspective is that the spacecraft was able to conserve some of the fuel that had been allocated for the Ultima Thule flyby. Fully operational and with a potent science package, New Horizons is good to go for further Kuiper Belt exploration.

Further KB observation – to where? What are the possible future targets for close flybys?

I’m sure there’s a preliminary list but no decisions yet, and more possible new discoveries on the way out could lead to a different selection.

New Horizons itself may be the best tool for finding its next target. It could be well worth a little delay in getting back UT data to take a few pics of the region its heading into.

These are faint objects moving very slowly. It may be tens of thousands of images we need to take for a search. It would be impractical to downlink all these images to Earth (don’t have the bandwidth over DSN), but with software mods, we hope to be able to do some of the processing and stacking of LORRI frames onboard the spacecraft.

There too much latency and bandwidth limitations to so such observations, it a lot easier and cheaper to do those observation on earth

We have a list of distant flybys (unresolved, <1 pixel) that we will be doing, but we have no candidate list for close flybys. That process, once started, will involve ground-based telescopes, Hubble, and/or LORRI imaging on NH itself. We didn't use this last mode for the MU69 search, but it's possible it would be of benefit for an upcoming search.

Great to have word from the inside from the New Horizons Hazard Team! Thanks, Henry.

Even distant flybys can reveal much, especially considering that we may not have another such opportunity for decades the way things are looking at the moment.

Considering how spot-on those occultation measurements were for 2014 MU69, are other such Earth-based observations planned?

The occultation campaigns were definitely critical to our success at MU69. If we find a suitable flyby candidate, then occultations could definitely help characterize it. With MU69 we had several years of lead-time to plan the occultations, and wait for the object to move in front of the proper stars. If we just have a few months, then doing an occultation before might not be possible.

Thank you Henry Throop for that information.

Very nice to learn you do have candidates already, though I understand that it might be hard to find good measurement for distance and speed and exact location for such faint objects.

And this I write hoping for more, even before we have learned much of what New horizons did find about MU69. :)

New Horizons is a non-biologic appendage to biologic based intelligence. As such extensions prove their usefulness by transcending the limitations of biology, they may be endowed with greater capabilities. The limitations imposed by space and time may necissitate the addition of increasing intelligence to make on-the-spot decisions.

Self replicating von Neumann probes could follow, ushering in a phase of post biologic intelligence.

Intelligent machines have only just started their evolution. They can only get much better, and very quickly. The military is also driving this intelligence too for battlefield weapons, so I expect this technology will be transferable to space probes as well, especially if it is miniaturized.

I will be looking out for the inclusion of neuromorphic chips to be used on space probes to execute such intelligence with low mass and power requirements.

How much autonomy a probe can be given will be interesting. How do its designers ensure that it will do what they want? It may be like training pets, and I know how hard that is with my cats.

My family once attended a show which had trained cats and dogs on stage. We talked to the person who ran the show and trained the animals afterwards. She said that cats were actually easier to deal with once they knew what you wanted them to do.

So we need to add animal trainers to the mission teams? ;)

In all seriousness, if our deep space missions are run by AI, they may need lessons and training in dealing with situations that call for emotional responses. Or am I just too 2001 HAL 9000 paranoia here?

I feel sorry for the programmers having to explain why the AI is being exiled to the infinite beyond…”Hello Hal, don’t take this personally but…”

Eek.

Greg Bear’s novel Queen of Angels plays interestingly with such issues, focusing on an AI probe orbiting a planet around Centauri B and gradually coming into true self-awareness.

The graphic series “2001 Nights” by Yukinobu Hoshino has a story I am Rocket where a ship rather like Discovery with a HAL 9000-like AI called KARC 9000 is sent on a one-way mission to the stars. The story is the elegiac reflections of the AI as it leaves the solar system on its 50 year long, lonely interstellar flight to Barnard’s Star.

Was not aware of that one, Alex. Thanks!

Meanwhile, much closer to home…

http://www.planetary.org/blogs/guest-blogs/2019/whats-next-for-china.html

Plans include a robotic lunar base.

Many here are likely already familiar with it but whenever someone brings up such topics I feel obliged to point people to the 1980 NASA summer study Advanced Automation for Space Missions edited by Freitas and Gilbreath. Yes, it’s now a bit dated but a great resource on self replication and includes a design for a self replicating lunar base. Such ideas I feel are key to really opening up the cosmos. Also available is Kinematic Self Replicating Machines by Freitas and Merkle from 2004.

https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/19830007077.pdf

Not having to maintain a collection of humans AND run base operations by using an automated station/base instead, whether in space or on a distant alien world, certainly makes sense from a logistics/expense/resource management point of view.

Buy also the distant worlds can be prepared for human arrival in advance. World ships can be resupplied enroute by smaller, faster automated vessels.

If we must be honest here, the only real reasons for humans to be in space is if we want to make colonies in our Sol system and beyond to preserve our species. The old let’s not keep all our eggs in one basket/cradle concept.

My mantra: Robots are for exploring, humans are for colonizing. The former can help the latter in this regard, but AI and technology is reaching a point where humans will not be necessary to explore space.

When Wernher von Braun envisioned a manned expedition to the Moon in the early 1950s, he had a fleet of ships with 75 men (yes, just men) as crew to handle multiple operations. Most if not all of those jobs can now be done far more easily and efficiently by machines with computer brains.

I know people want boots on the ground out there, but this will not happen for several decades even with all the renewed enthusiasm, and I am sure most people reading this know how easily that could change overnight. Machines have taken us places we would still be ignorant of otherwise and they will only get better.

There will likely be human venturers into the galaxy one day, but they will be doing so mainly to preserve themselves and our species by proxy. Also keep in mind that our descendants may be quite different from current humanity thanks to cybernetics and bioengineering.

I mostly agree with the caveat that NASA has long been controlled by the scientific lobby that treats human space flight as an unnecessary luxury detracting from ‘real science’. Even the Shuttle flights were mostly about science. Humanity should not have to justify living on more than the surface of one planet any more than living on more than one continent.

Thank you for the link. It is quite fascinating to see how developments in AI have changed since that document was published in 1982, and the limitations the authors had to deal with. However, we still cannot get to full self-replication for any machine that needs microchips, as this still requires large fab technology. So perhaps partial self-replication given a supply of chips.

Does the spacecraft have any ability to sort through the photos and data before sending them in order to select better targets quicker? I realize from an earlier discussion that the data rate for sending back information is very low but local processing speeds could be higher.

The spacecraft would have to stack multiple exposures in order to show the very faint targets, and then subtract the numerous stars that would be in the image. After that it would have to tell if there was something non-stellar remaining, and send back any promising candidates. This with a CPU like the one in a PlayStation One.

https://apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap190129.html

Ultima Thule from New Horizons

Image Credit: NASA, JHU’s APL, SwRI; Color Processing: Thomas Appéré

Explanation: How do distant asteroids differ from those near the Sun? To help find out, NASA sent the robotic New Horizons spacecraft past the classical Kuiper belt object 2014 MU69, nicknamed Ultima Thule, the farthest asteroid yet visited by a human spacecraft.

Zooming past the 30-km long space rock on January 1, the featured image is the highest resolution picture of Ultima Thule’s surface beamed back so far.

Utima Thuli does look different than imaged asteroids of the inner Solar System, as it shows unusual surface texture, relatively few obvious craters, and nearly spherical lobes. Its shape is hypothesized to have formed from the coalescence of early Solar System rubble in into two objects — Ultima and Thule — which then spiraled together and stuck.

Research will continue into understanding the origin of different surface regions on Ultima Thule, whether it has a thin atmosphere, how it obtained its red color, and what this new knowledge of the ancient Solar System tells us about the formation of our Earth.