If we were to find an asteroid on a trajectory to impact the Earth, what strategies would we use to stop it? Recent work from Johns Hopkins University shows that there is a wide range in our thinking on what happens to asteroids under various mitigation scenarios. Much depends, of course, on the asteroid’s composition, which we must account for in our models. A good thing, then, that we are supplementing those models with sampling missions like OSIRIS-REx and Hayabusa-2.

Let’s look at the JHU work, though, which updates earlier results from Patrick Michel and colleagues, reported in a 2013 paper; the latter had considered the 5 km/s head-on impact of a 1.21 km diameter basalt impactor on a 25 km diameter target asteroid, with a model varying mass, temperature and material brittleness. Michel’s work showed evidence that the asteroid being targeted would be completely destroyed by the impactor. What Charles El Mir and colleagues at Johns Hopkins have been able to show is that other outcomes are likely.

“We used to believe that the larger the object, the more easily it would break, because bigger objects are more likely to have flaws,” says El Mir. “Our findings, however, show that asteroids are stronger than we used to think and require more energy to be completely shattered.”

Using essentially the same scenario as Michel, El Mir, K. T. Ramesh (JHU) and Derek Richardson (University of Maryland) have created a new model that offers a more detailed look at the smaller-scale processes that take place during such a collision. “Our question was, how much energy does it take to actually destroy an asteroid and break it into pieces?” adds El Mir.

Discussing methods, the authors note their model’s calculation of the first tens of seconds following impact, with transition to computer code integrating longer-term effects. From the paper:

The multi-physics material model is centered around the growth mechanism of an initial distribution of subscale flaws. Rate effects in the model are a natural outcome of the limited crack growth speed, which is explicitly computed based on the local stress state. In addition, porosity growth, pore compaction, and granular flow of highly damaged materials are captured at the material-point level. We validated the model’s predictive capability by comparing the dynamic tensile strength with high-strain-rate Brazilian disk experiments performed on basalt samples.

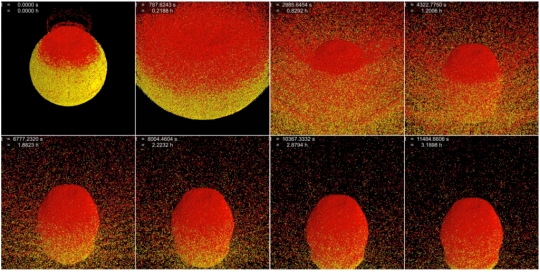

Image: A frame-by-frame showing how gravity causes asteroid fragments to reaccumulate in the hours following impact. Credit: Charles El Mir/Johns Hopkins University.

The first phase of the scenario is shown in the video below, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=Vt_xwQYafOY for email subscribers who would like to follow it up in their browsers. What emerges is that millions of cracks form in the asteroid as the crater is created, with the asteroid surviving the hit rather than being shattered, while the surviving core then has sufficient gravitational pull to act on the fragments swirling around it.

In the second phase, available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=ZjBgljnCtWk, what we have left is not a rubble pile held loosely by gravity, but rather a surviving core whose fragments have been redistributed. Can we, then, hope to break an asteroid into small pieces, or is it best to find ways to nudge the entire object onto a new trajectory? The latter still involves the question of asteroid survivability, as we need to move it without breaking it into smaller impactors.

The paper shows the capability of the parent asteroid to withstand huge shock:

The collision imparted substantial damage onto the target, with most of the damage localized under the impact site, resulting in a heavily fractured but not fully damaged “core”. The material points were then converted into soft spheres and handed over to pkdgrav [the modeling software] in a self-consistent manner to calculate the gravitational interaction of the ejected material. We observed substantial ejecta fallback onto the largest remnant of the parent body, with a recovered mass of the largest remnant being 0.85 that of the parent body, indicating that the disruption thresholds for such targets may be higher than previously thought.

Thinking ahead to asteroid mitigation strategies is simple prudence, and requires continuing study of how asteroids respond to the various methods now under consideration to destroy them or change their trajectory. This paper gives us a glimpse of the changing parameters of research on the matter, a window into the ongoing analysis that will refine our planning.

The paper is El Mir et al., “A new hybrid framework for simulating hypervelocity asteroid impacts and gravitational reaccumulation,” Icarus Vol. 321 (15 March 2019), pp. 1013-1025 (abstract). The Michel paper is “Collision and gravitational reaccumulation: Possible formation mechanism of the asteroid Itokawa,” Astronomy & Astrophysics 554, L1 (abstract).

This question has been realistically addressed by certain national laboratories. I believe the consensus is that if we wish to have some degree of certainty in that averting such a collision that the best course of events is to use a nuclear explosive.

Now we have all been conditioned through watching Hollywood movies such as “Deep Impact” and “Armageddon”, but in reality use of explosives in this manner would probably be ineffective.

Thinking of scientists at Los Alamos suggest that using the nuclear explosive as a radiation source (e.g., light, microwave, radio, etc.) so that radiation pressure can divert the object is a more reasonable objective. Applied at a great distance, and when the asteroid is relatively slow would probably be enough to nudge it off target.

Nukes can’t “destroy” any asteroid big enough to be a threat. The mechanism is that they will act like shock-absorbers.

Those keywords “Nukes, propulsion, shock-absorber” gets you the solution to how to divert dangerous asteroids in realistic timeframes. You treat the asteroid itself like an Orion baseplate.

Studies like this should also be able to explain how asteroids are processed in space. We know that some show material differentiation, suggesting that they were larger bodies that were broken up after accretion. Nickel-Iron asteroids should result from such impacts (I presume).

High impact collisions do generate heat that can result in localized melting, but if there are long periods between impacts things cool off too quickly for much settling of heavy elements. Plus the majority of impacts would be small and wouldn’t heat clear to the core.

This is why it is thought that radioactive heating was important to provide the heat needed to melt the interior of asteroids. There would have to have been much more radioactivity in the early days of the solar system. Al26 for example, but many others also.

I think I must have expressed myself badly. What I was trying to say was that in order to get differentiation of material, the asteroid must have accreted sufficient mass to create the gravity needed to separate the heavier elements such as iron from the lighter elements. Obviously heat was also needed.

But as we see isolated iron asteroids, this implies that the stony and volatile materials have been subsequently separated from the iron “core”.

When I was young, one theory was that the asteroid belt was due to an exploded 4th planet. [Am origin of which was explained in a delightful Brian Aldiss SF short story “T”].

My thought was that subsequent impacts exposed the metal core instead. The mechanism results such impactors could be simulated in the sort of studies in the El Mir paper.

If this is not the case, then there needs to be an explanation for this differentiation that precludes this prior accretion and subsequent breakup mechanism.

I though it was well know that nuclear devices can be set up like

a shape charge. You can try and shatter pieces off, and having

the momentum of the explosion propel those pieces far away from

the main body, too far for gravitation to reassemble the pieces.

You don’t need to shatter the whole asteroid at once. flaking off

large chunks would work too. Hey ! a use for MIRV missle tech.

Sounds like an Orion nuclear pulse rocket would come in very handy for such a situation…

https://centauri-dreams.org/2016/09/16/project-orion-a-nuclear-bomb-and-rocket-all-in-one/

The concept would also be useful for moving around planetoids and comets in general to assist in mining efforts and making habitats, either separately or as WorldShips/O’Neil colonies themselves. And of course they could be used as propulsion should said habitat inhabitants decide to venture off to other star systems.

Somehow I would advise against using nuclear devices as a shaped charge type of fragmenter ; the reason I advise against it is the fact that you would like to control the asteroidal body as a whole entity rather than as a series of fragments. You’d like to be able to impart a nudge to the entire body at once rather than having to deal with a whole group of separate pieces. You’re not guaranteed that the individual pieces would be necessarily driven off course, that’s why you wouldn’t want to do this.

If a fragment was not driven off course, then that would necessitate further actions to divert that fragment and that means greater complexity and additional resources that you might not just necessarily have at hand. Then what do you do?

Before you would light off a nuclear explosive to use the radiation pressure you might wish to make a determination as best you could of where the center of mass of the asteroid would be such that you would have some degree of certainty where the radiation pressure could be reasonably directed to have a high degree of success. Nuclear fragmentation would certainly be an exciting event to witness, but given the stakes of what is going on, you don’t really want to be fooling around, at that particular juncture, just to get some spectacular fireworks. You’d have a job to do and that would be the important thing.

What is this fascination for blowing stuff up? I understand that this might be a needed last ditch approach when a lot of energy is needed because an asteroid managed to avoid early detection, but I would had thought that early detection and more subtle means to divert asteroids would be preferable.

Destroying asteroids would mean defense in the hands of the military and the creation and deployment of weapons. Nations will not believe such devices are only for planetary defense. If instead, we build better detection systems and craft designed to gently deflect asteroids over long periods, we build useful technologies and a rationale for space industries. Slow deflection can be monitored by any nation to confirm the trajectory change is benign and not an attempt to use asteroids as some sort of orbital bombardment on their nation.

Agree completely. The study under discussion here points out how hard it would be to completely pulverize an asteroid and to accurately predict the size and trajectories of the fragments. Thus the take away should be that advanced warning is paramount. The more advanced warning, the greater the odds that some moderate means can be found and used to avoid the collision.

With enough knowledge of earth orbit crossing objects we can push such threats into safe orbits, turning them into very valuable assets instead of grave dangers.

No one is saying they have a fascination with blowing things up; that’s an extremely unfair accusation. There is a lot of pie-in-the-sky type of ideas that sound good on paper but I can assure you that if you think about them even slightly you begin to question their validity. What’s wrong with going with a proven technology, and what’s with all the fear factor that you talk about and suggest that the worst will occur if you follow known principles?

Following my suggestion will not end up making current international relations any worse than if you didn’t follow them.

I am not accusing you of anything. What I am trying to say that whenever the issue of PHAs comes up, the conversation seems to inevitably to discuss using nukes to destroy them. Whether this is the specific result of too many SF B-movies that want something spectacular , or the more general visceral violence of our species that is displayed in popular culture from as far back as we have history, I don’t wish to speculate. There are many possible gentler ways to prevent collisions which do not require destroying these asteroids using such such destructive means. As I tried to suggest, the spinoffs might even benefit our development of such tools.

Also, I don’t think it that pointing out that nukes are dual use tools at best is particularly alarmist. I would point out that we signed a treaty preventing such weapon deployment and use in space. No nation can be trusted to deploy such weapons in space as a standby for planetary defense given that the leadership might decide to use them as weapons. If they must be used, then we need international agreements in place on how they may be deployed and when they may be used so that such potentially dangerous devices are under international control.