These are unusual times for a site that usually begins its investigations no closer than the outer Solar System (asteroids are an exception). But there is no way to ignore the Apollo 11 anniversary, nor would I even consider it. Tomorrow I’ll have further reminiscences from Al Jackson, who was on the scene in Houston when Apollo touched the Moon, and on Friday a piece from Neil McAleer with substantial portions of a speech Neil Armstrong gave in Australia in 2011.

For today, a look at how the public views space exploration in our era and earlier, with the surprising result that there seems to be more interest in space than I had assumed. In fact, while it has often seemed as if interest peaked with the moon landings and then slackened, turning instead to space programs of the imagination via high-budget films, there is new evidence that the work we track on Centauri Dreams has a good deal of support.

According to a recent survey, over 70 percent of Americans liken the exploration of space to the European voyages that opened up the western hemisphere and established outposts and trade routes throughout Asia and the Pacific. That’s a higher number than I would have expected, one that reflects, in the words of Jon Miller, director of the International Center for the Advancement of Scientific Literacy at the University of Michigan’s Institute for Social Research, “…the deep-seated impact of the first moon landing in American culture.”

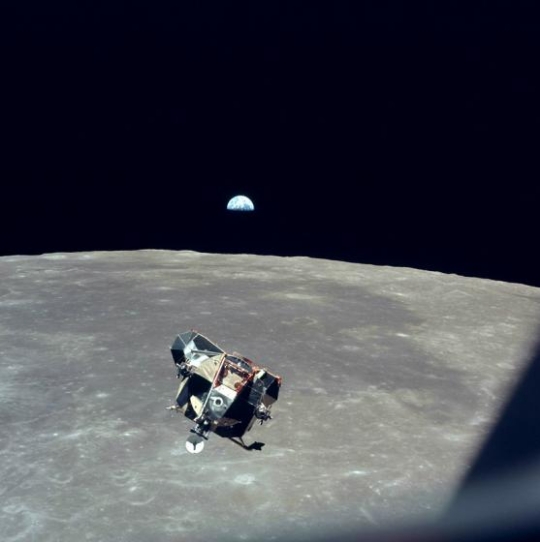

Image: Taken by Michael Collins, this photo shows the lunar excursion module, the Moon, and the Earth from Columbia, the command module, as Armstrong and Aldrin return from the lunar surface. Credit: NASA.

So is this a simple nod to a cherished memory? After all, those who were alive in those days will never forget the experience, a global one, of leading their daily lives with one eye always on the three astronauts on their way to the Moon. Maybe there’s more to it than that, given that the percentage of adult Americans who were alive on July 20, 1969, is only 45%. There does seem to be some movement in peoples’ perception of space exploration, one that this survey tracks.

We’re dealing with the Michigan Scientific Literacy Study, compiled in 2018, with data collected by AmeriSpeak, which is a service of the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago. The survey was taken in November and December of last year and included both online and telephone interviews with 2,312 adults age 18 and older. I have no expertise whatsoever in such surveys, and so cannot judge this one’s accuracy. But let me quote it:

A national survey conducted in 1988 found that 67% of American adults agreed that we should think of space exploration in terms similar to the early explorers of this planet. Thirty years later, a 2018 national survey found that 72% of American adults agreed with the same statement. This level of continuing general support for space exploration indicates that most Americans see the last six decades as a period of positive achievement and that they are supportive of continued efforts to explore space.

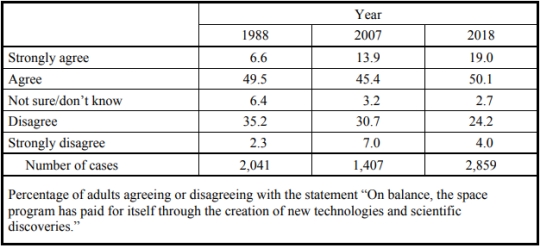

Again, I’m surprised. Maybe I’ve been too pessimistic. The study from thirty years earlier refers to the work of the Public Opinion Laboratory at Northern Illinois University, which sampled 2,041 adults by telephone on the same topics. This one was published in the National Science Board’s Science and Engineering Indicators for 1988. The current survey repeated a question from 1988’s survey, asking for agreement or disagreement on this statement: “The space program has paid for itself through the creation of new technologies and scientific discoveries.”

Here again the numbers were something of a surprise, at least to me. Thirty years ago, 56 percent of adults agreed with the statement. In 2018, that percentage had risen to 69%. That’s a fairly robust figure, and it removes the perceived benefits of the space program from the experience of having watched the Apollo missions themselves. Says Miller: “This pattern reflects a long-standing public belief in the indirect benefit of the space program apart from spectacular events like the lunar landing.”

The question I mentioned in the first paragraph on the exploratory impulse asked respondents to agree or disagree with the statement “The United States should seek to explore space in the same spirit that led Europeans to explore this planet in earlier centuries.” 1988’s figure was 69 percent, roughly the same as the 72% tagged in the 2018 results. Interestingly, older adults were more supportive of this view in 2018 than they were in the earlier survey, while men were more supportive than women, though with a difference that has narrowed over the years.

You can see the results of the 2018 survey here. Another excerpt:

This brief examination of national survey data from 1988 and 2018 indicates that American adults tend to recall the first Apollo lunar landing as a landmark achievement of the space program, citing it more often than any other activity as the best achievement of the space program. Parallel national survey data indicate that a majority of American adults think that the space program has paid for itself through the development of new technologies and new scientific discoveries. The proportion of American adults holding this belief has increased steadily over the last 30 years.

Here’s the survey’s Table 2, labeled “Public agreement with statement concerning the value of new technologies from the space program, 1988-2018.”

What to make of all this? It’s heartening to see the rise, a steady one, in the proportion of adults who believe the space program has been worthwhile in producing new technologies and generating scientific data. This recognition of the program’s value and the substantial majority of Americans who see space exploration as similar to earlier periods of exploration shows that there is public support for future missions. At the same time, note this: One in five adult Americans were unable to recall any achievements of the space program.

Let’s go with the other 4/5ths. It’s no surprise that, for them, the landing of Apollo 11 on the Moon ranks as the most important result of the space program in its first 60 years, and the media attention to Apollo accompanying the anniversary reinforces that perception. But even as more than 70 percent of Americans want to see space exploration continue, there is no information within this work that shows us how to translate this interest into larger budgets for space.

Remember that Apollo at one point was absorbing 4.4 percent of the federal budget. According to a recent analysis by The Planetary Society (reported in this CBS news analysis), that is the equivalent of spending NASA’s current annual budget on a single project and sustaining the effort for over a decade, some $288.1 billion in inflation-adjusted dollars. This at a time, at least in the earlier ’60s, when rather than today’s gigantic deficits, the United States had a budgetary surplus and increased spending as a way to stimulate the economy was much in the air.

So while a new Gallup poll backs the University of Michigan study that most Americans support space exploration, the kind of big-ticket effort that Apollo represented is ruled out by financial realities. Even so, exciting exoplanet discoveries and spectacular one-off missions like New Horizons are holding the public’s interest, and there is a sense that space delivers tangible results in everyday life as well as scientific return. As we celebrate Apollo 11, then, we can remember how unique the entire Apollo effort was while recognizing that there is still support for creative missions that expand the human spirit while operating on a much slimmer budget.

It would be fascinating to see similar polling on space in Europe and Asia. If anyone has any leads on such, please let me know.

“Image: Taken by Michael Collins, this photo shows the lunar excursion module, the Moon, and the Earth from Columbia, the command module, during landing operations. Credit: NASA.”

Sorry to be pedantic, but either the photo caption means something different from how I interpret it, or it is just wrong. To state the obvious, the LEM is missing the descent stage. Therefore landing operations are in the past. The LEM has ascended and completed the rendezvous operation, and is prepared for the docking operation.

Fair enough. I’ll re-phrase it.

In old film and some documents the term Lunar Excursion Module is heard and seen. When I was in the program in the 60’s word came down to drop the term ‘excursion’… someone up the line thought ‘excursion’ sound like a boondoggle. I can’t remember anyone making much out of that, but LM is shorter than LEM. In fact most of us had dropped the ‘E’ anyway , just seemed more compact to say LM.

NASA’s History Web site has the book Chariots for Apollo online in PDF format here:

https://history.nasa.gov/SP-4205.pdf

In the documentary “8 Days to the Moon” the audio from mission control after the CM docks with the LM, seems to indicate that the controller says “Lem”, not “El-Em” as would be expected for LM. Is that because it is easier to say it that way, or for some other reason?

[source approx 19:45 into the documentary]

Overview: Earth and Civilization in Macroscope

by Ahmed Kabil on May 29th, 02018

“Once a photograph of the Earth, taken from outside, is available…a new idea as powerful as any in history will be let loose.“? —?Astronomer Fred Hoyle, 01948

https://blog.longnow.org/02018/05/29/overview-earth-and-civilization-in-macroscope/

To quote:

In the aftermath of World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union competed for nuclear dominion on Earth. With the 01957 launch of Sputnik, the contest expanded to space. But in the race to the moon, neither side had given much thought to the value of training their satellites’ apertures on the world left behind. Brand glimpsed the power such an image could hold.

“A photograph would do it?—?a color photograph from space of the earth,” Brand said. “There it would be for all to see, the earth complete, tiny, adrift, and no one would ever perceive things the same way.”

Brand mounted a spirited campaign selling buttons that posed the question “Why Haven’t We Seen A Photograph of the Whole Earth?” on college campuses across the country. He often showed up in costume, and he often was chucked out by security. He sent buttons to Marshall McLuhan, Buckminster Fuller, NASA officials, and members of Congress.

According to a 01966 Village Voice article, a student at Columbia asked Brand: “What would happen if we did have a picture? Would it eliminate slums, or meanness, or anything?”

“Maybe not,” said Brand, “but it might tell us something about ourselves.”

“What?” asked the girl.

“It might tell us where we’re at,” said Brand.

“What for?” asked the girl.

“Why do you look in the mirror?” asked Brand.

“Oh,” said the girl, and bought a button.

Tom Murphy is an astrophysicist working for NASA measuring the movements and distance of the moon by laser interferometry to centimeter precision. He also holds a faculty appointment at UCSD.

Why Not Space?

Apolloinrealtime.org

Continuous real time replay of entire Apollo mission from t-21 hours to Splashdown at t+198:08:31:08 h.

Amazing work from Ben Feist software engineer and historian at JSC and Goddard.

50 channels. 11,000 hours original mission audio. Presented here for the first time.

AN ELEGY FOR THE AGE OF SPACE

By John Michael Greer, originally published by The Archdruid Report

August 24, 2011

The comparison to the European voyages is an apt one indeed. As we see several nations and even Blue Origin as a private entity vying for the Lunar South Pole, and others prospecting asteroids like Ryugu, we should recognize that we are no longer talking about idle curiosity or human knowledge. ( https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2019/05/why-moons-south-pole-may-be-hottest-space-destination-blue-origins-shackleton-crater/ ) One day we are going to wake up and the Moon above our heads, like the asteroids before it, will somehow have been magically changed from being the province of deities or the common property of mankind to being the very specific property of a very few people who are not us. It will be their sole privilege to decide whether the ice feeds space probes or interplanetary ballistic missiles, but we can look to the history of Europe to make a prediction.

Beat me to it: The “spirit that led Europeans to explore this planet in earlier centuries.” was a spirit of exploitation for profit, and colonization, not disinterested scientific inquiry.

Perhaps that’s why public approval is rising: We’re finally starting to approach space in the way the average guy thinks it should be approached: As a rich new resource, not an interesting scientific puzzle.

The exploration of the planet in centuries past was in wooden ships driven by the wind and once they arrived on the far shore there was air to breathe, water to drink, food to eat, and a support system to exploit. Landing on the moon or on a planet has no support system in place. Air, water, food must be supplied at an astronomical cost. There is no resemblance of one to the other.

As we learn how to produce air, water, food, fuel and machinery from the ice, rock and sunlight that are plentiful in space, the support system will be there and the resemblance will carry through.

Water falling from the sky, running free in streams. in no way resembles baking it out of rock. Produce air? Well take some nitrogen and some oxygen – from only God knows where – and you have air for a few minutes of breathing. There is only one place in the known universe where people can live long and prosper – Earth. Even though I have always loved sci-fi, since I was 12 years old I have known it was fiction.

To be fair, settlers in the American SW had to sink wells for water, so it wasn’t often running free in streams, nor often falling from the sky.

As we now know, there is water at the lunar poles, and water in abundance beneath the Martian surface. So water is not an issue any more, and simple technologies can be used to extract it. Where there is water, there is O2, which again is easy to extract. So while O2 may always be in short supply (a popular trope is control by corps), a settler can at least breathe. More problematic are sources of C, N, P. All these are needed to survive. All are available in tiny amounts in lunar and Martian regolith, although I suspect that, like water, cold traps for cometary volatiles will prove the more import sources. Maybe Titan becomes the N2 source for the outer worlds.

Heinleinian style. self sufficient farmers are not going to happen in our solar system. However, I do see technology solving the problems you cite. Just as the Inuit couldn’t survive in the Arctic regions without technology for clothing, shelter, and fishing, I see colonists in our solar system bringing the needed technology to allow survival on other worlds. (European settlers in the US had to bring in metals long before local production became important in the 19th century. There were no free and abundant sources of refined Fe to be used.) Loners need not apply, as the colonists will need to use the power of specialization and community to ensure sustainability. Buying access to air and water, in addition to food and shelter, should be no particular problem for our colonists. Recycling of needed elements will be very important. (E.g. CO2 scrubbers will have recyclable elements to allow the CO2 to be extracted and resold in various forms).

Realism, rather than pessimism, should apply, and never bet against human ingenuity. ;)

Found it in Wikipedia:

“In June 1966, the name was changed to lunar module (LM), eliminating the word “excursion”.[14][15] According to George Low, Manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office, this was because NASA was afraid that the word “excursion” might lend a frivolous note to Apollo.[16] After the name change from “LEM” to “LM”, the pronunciation of the abbreviation did not change, as the habit became ingrained among engineers, the astronauts, and the media to universally pronounce “LM” as “lem” which is easier than saying the letters individually.”

I certainly recollect it being called the LEM here in the UK. I was only a kid at the time but I had a lot of literature on Apollo. Wish I had saved it !

You just answered the question I posed earlier. I should have read the whole thread first.

But what about Stanislaw Lem?

I wonder if we should turn this on its head. Perhaps the many high-budget SF (well mostly fantasy) movies stimulated the idea that we should explore space. Early Sf movies, with few exceptions, were schlocky B-movies that most people did not take seriously. Now we have an abundance of SF in movies and tv that have become part of the culture. Even Star Trek is still going strong! Couple this with the sense that teh world is shrinking and becoming more unsafe from human and natural events, it may seem that finding “New Edens” is attractive. As we have discussed elsewhere, most of the public think star flight distances are like travel to the next big city, achievable quickly with some soon to be available FTL propulsion. With exoplanet discoveries routinely described as “New Earths”, who can wonder that travel and colonization of these untouched worlds isn’t attractive.

If those expectations can be managed so that there is no backlash when reality dawns, I would even encourage such ideas if it meant we could divert spending from the military to [human] space exploration. It is likely to be more economically productive and far less wasteful. I think Philip K Dick explored such ideas in several of his novels.

I definitely concur that science fiction has had a huge impact on humanity’s perceptions of where and why we should be in space. Many people, including those who neither have any interest in the subject nor support space efforts, see our permanent expansion into the Final Frontier as a given largely based on this.

I discuss this very issue here in my essay on the film Forbidden Planet, which presumed humanity spreading into the Milky Way galaxy one year before Sputnik 1 was launched:

https://centauri-dreams.org/2017/09/11/creating-our-own-final-frontier-forbidden-planet/

Forbidden Planet was a huge influence on Star Trek, which I would argue has probably done more to positively promote humanity in space than any other type of science fiction.

That being said, as I also discuss in my essay linked above, I also think FP and ST are now antiquated views on how we should and could reach deep space that may even limit, delay, or even stall our chances of reaching the stars.

I should have referenced you, as I recall you made that point then.

Interesting that one of the authors of a recent book about Apollo ‘Chasing the Moon’ asked me if I knew a lot of science fiction fan when I worked in the Apollo program.

He knew I had been in science fiction fandom in the 1950s , I mean tru blu SF fandom… I still kinda sorta am tho it is very marginal.

When I came to Houston in Jan 1966 , to work in Apollo, I ran into a lot of people who read science fiction, about half the people I worked with were knowable , tho it was mostly Heinlein, Asimov and Clarke (some added Bradbury)…

I didn’t meet a single fan! In the SF Fan sense of the word. I did join the Houston Science Fiction Society made up of Fans.

I think this is still true , a lot of readers, more now, not many involved in fandom, which is broader these days.

I did find out Buzz Aldrin was well read in SF… no surprise… I know some other astornauts were , some others never read SF.

But we all forget the real result of this project and that is that the earth is a fragile planet and has been destroyed many times in the last 600 million years. Theories of Geological Evolution Catastrophism vs Uniformitarianism, Catastrophism has been proven to be correct via impacts causing mass extinctions and even the mechanism that started plate tectonics. The public is very supportive of protection of Earth from future impacts and exploring asteroids.

No, what this demonstrates is that any one species, such as humanity, is fragile. The planet and its ecosystem survives very well, and will again if it comes to pass.

Also, that catastrophic events occur is not an argument that incremental change doesn’t occur, when in fact it is dominant.

Paul, there is a book The Lights in the Sky are Stars by Fredric Brown, 1953. The scenario was that the USA had a vigorous space program that went right in the dumper! Reads a bit dated now but Brown nailed it. Fred Brown is an unjustly , bit forgotten, science fiction writer, some classic science fiction written by him… including Martians Go Home , the most off center funny alien invasion story ever written.

I remember it well, Al. I can still see the cover illustration on my paperback of The Lights in the Sky are Stars. And yes, Martians Go Home was a zany thing indeed!

American kids want to be famous on YouTube, and kids in China want to go to space: survey

https://www.businessinsider.com/american-kids-youtube-star-astronauts-survey-2019-7

A recent survey of 3,000 kids found that being a YouTube star was a more sought-after profession than being an astronaut among kids in the US and the United Kingdom.

Children ages 8 to 12 in the US, the UK, and China were recently polled in honor of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission, which resulted in the first person to walk on the moon.

Kids in the US and the UK were three times as likely to want to be YouTubers or vloggers as astronauts, while kids in China were more likely to want to be astronauts.

I disagree with only one thing financial realities. We the US is running a trillionbdollar deficit with tax cuts …..With the democrats embrace of MMT we are only limited by what we want to print it for.

A few years back I accidentally started an acrimonious debate here by raising that very point — that a government that controls its own currency can create any amount of it at any time, so economic activity is limited by available resources and not by the ability to pay for those resources. In the U.S. there are no doubt thousands of scientists and engineers, and many aerospace firms, that are available to participate in an expanded space program. If we choose not to pay for their participation that is a political choice, not an economic necessity.

The link between printing currency and inflation is established. The government must balance currency (and borrowing – M3) with the demand for money. MMT claims this is not the case, but the onus is on MMTers to show this, and I’m not keen to do this experiment on a country as large as the USA.

Because we have a climate emergency, it does make sense to change policies and stimulate the economy to transition quickly to a net zero carbon economy. This is similar to the existential threat on the Axis powers in WWII and the need to convert the US to a war production economy. That did cause inflation, but it was also coming out of deflation caused by the contracting economy of the Great Depression.

The worst outcome would be to print money, juicing the “business as usual” economy which raises CO2 emissions, and adds to inflation.

Btw these are considered good surveys. Aeoospace has lobbyists they need to have these surveys with them. Also Breakthough Starshot 10 billion is a rounding error in what we spend and focus onnthe spinoffs. I think BSS has the greatest tech breakthough potential for dollar spent.

Apollo was 25 billion . Based onnthe Feds PCE deflator…..that is about 125 billion today. Breakthrough is potentially the biggest space bargain ever.

It’s an imperative.

I remember seeing the LEM take off from the Moon on a small color TV as a boy. There were was also the books by Life magazine like Man in Space and Universe which implied we might have astronauts on Mars by the 1980’s. Nothing much was happening with astronauts in the mid to late 1970s, but those reruns of Star Trek and Lost in Space were inspiring my interest in astronomy and space travel. Along came Star Wars in 1977 when I still was collecting Marvel comic books and Battlestar Galatica afterwards which really got me back into astronomy and planetology, so I eagerly awaited the space shuttle launch. I was a senior in high school when the Columbia launched, so the science fiction as Alex Tolley remarked played a role in increased interest.

Also our technology has improved as the result of space travel and it has affected everyday life on Earth as well. The Apollo Moon landings of our astronauts have discovered the evidence for the Giant impact hypothesis which is a big scientific discovery. It’s much harder to travel to Mars, but once were are able to go there often we will have interplanetary travel technology. Astronauts can still make some big discoveries there geologically and possibly fossils of ancient, Martian life.

One thing I have always wondered about is what would have happened if in the early 70’s the Soviets somehow got their N1 rocket to work and so they did not kill their moon program. I recall reading that they even had some plans to eventually set up a small Lunar base. Would the US then keep some kind of moon program going ? Has any NASA official ever comment about this ?

There’s a Tiny Art Museum on the Moon That Features the Art of Andy Warhol & Robert Rauschenberg

in Art | July 18, 2019

This week is the 50th anniversary of the moon landing, and though we have yet to send an artist into space (photographer Michael Najjar is apparently still training to become the first), there is a tiny art museum on the moon, and it’s been there since November 1969, four months after man set foot on the lunar service, and in the afterglow of that amazing summer.

Don’t expect a walkable gallery, however. The museum is actually a ceramic wafer the size of a postage stamp, but what an impressive list: John Chamberlain, Forrest Myers, David Novros, Claes Oldenburg, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol.

Full article here:

http://www.openculture.com/2019/07/tiny-art-museum-on-the-moon.html

To quote:

The artwork was not the only object sent to the moon on that mission. Engineers placed personal photos in the same place: in between the gold thermal insulation pads that would be shed when the lander left the moon’s surface.

Only when Apollo 12’s re-entry capsule was on its way back to Earth did Myers reveal to the press his successful stunt. However, unless we sent astronauts back to the exact same spot we don’t really know if the museum ever made its way there. Maybe it landed the wrong way up? Maybe other wafers moved in through gentrification, raised rents, and the moon museum had to move to Mars. We’ll never find out.

The problem with the N1 rocket was that it’s plumbing was to complicated and fragile since it had to connect to many engines, so the fuel lines broke too easily. Also Korolev, Russia’s brilliant rocket scientist died before the completion of the N1. They did have the proton rocket but work continued on the N1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/N1_(rocket)

Having working in manned space flight for 45 years the current hiatus is no surprise. One thing is. After the last Shuttle Flight I did not expect that the USA would not currently have NO manned access to low Earth orbit. This is till odd to me. Using current boosters and a little money spent on a manned spacecraft would have given access to the ISS. There was a plan but that got dumped sort of arbitrarily. Looks like Space X or Boeing will have something ready soon. Space X seemed in the lead but had a set back recently.