Ongoing in Geneva is the joint meeting of the European Planetary Science Congress and the Division for Planetary Sciences of the American Astronomical Society. We can abbreviate the whole thing as EPSC-DPS 2019, and you can read more about it here. We’ll track several stories here as they develop, but I notice that the European Space Agency’s ARIEL mission, which is slated to make the first large-scale survey of exoplanet atmospheres, has been supporting a Data Challenge involving removing noise from exoplanet observations. So let’s start there.

The slant here is training computers to filter out errors in collecting exoplanet data caused by starspots and by instrumentation, with two winners, James Dawson (Team SpaceMeerkat), and Vadim Borisov (Team major_tom), announced yesterday in Geneva. All told, 112 teams registered for the competition, a heartening number illustrative of the growing interest in computational statistics and machine learning among exoplanet researchers. The top five teams in this first international Machine Learning Data Challenge will present their methodologies to the European Conference on Machine Learning (ECML-PKDD 2019) on Friday.

Says Nikos Nikolaou (UCL Centre for Exochemistry Data), who created the competition:

“The outcomes of the competition exceeded our expectations, both in terms of the quality of the technical solutions submitted and in the massive numbers of entries for the challenge, which rivalled participation in open machine learning competitions with large monetary prizes.”

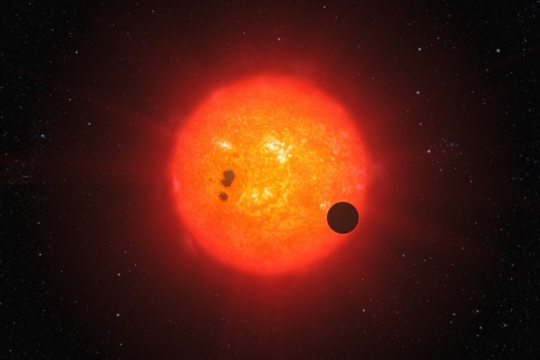

Image: Space mission data analysis is not easy, especially if you need to observe a planet passing in front of its star that is often 100s of lightyears away. At such distances, one of the main issues is differentiating what is planet and what is star. The Machine Learning ARIEL Data Challenge tackled the problem of identifying and correcting for the effects of spots on the star from the faint signals of the exoplanets’ atmospheres. This image shows a transiting planet passing in front of a star with stellar spots. Credit: ESO/L. Calçada.

ARIEL, which I mentioned last week, stands for Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey. ESA is also launching what it calls the ‘ExoClock’ project to collect transit light curves. Here we turn to the community of amateur astronomers for assistance, for transits can be measured by small telescopes when properly equipped, and a growing number of amateurs have the needed hardware. The idea is to enlist a global community of observers to gather light curves that will be used by the ARIEL mission to improve the accuracy of transit timings, so the spacecraft will be armed with the best data on the exoplanets on its target list.

“This is the first open call to join the ExoClock project and we encourage all interested observers to become part of ESA’s ARIEL mission. Every transit observation is unique and important. By participating in ExoClock, citizens all over the world can contribute to the success of the ARIEL mission,” says Anastasia Kokori, who announced the launch of ExoClock at EPSC-DPS 2019.

Online resources are being set up to support the effort with a platform that includes an alert system to maximize the coverage of individual exoplanet targets and a system of target prioritization that allows individual users to have a personalized schedule based on their equipment and their geographical location. The light curves will be submitted and published along with analysis on the ExoClock website and may be included in scientific papers.

To learn more or to receive training in transit observations, go to the ExoWorlds Spies project (exoworldsspies.com). Experienced observers can register directly at exoclock.space. This citizen science opportunity is one that factors directly into the upcoming ARIEL mission, scheduled for a 2028 launch. Principal investigator Giovanna Tinetti comments on both the machine learning data challenge and the Exoclock effort:

“ARIEL is a challenging mission that’s pushing the boundaries of exoplanet research. The Data Challenges and ExoClock project are enabling us to build a global community of collaborators with a diverse mix of skills and backgrounds. We look forward to working with them over the next few years to develop networks, tools and analysis techniques in preparation for the mission’s launch in 2028.”

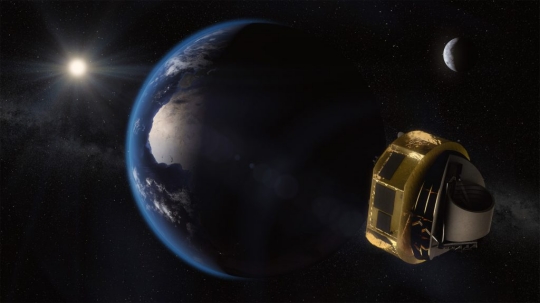

Image: Artist’s impression of ARIEL on its way to Lagrange Point 2 (L2). Here, the spacecraft is shielded from the Sun and has a clear view of the whole sky. Credit: ARIEL space mission/Science Office.

ARIEL will be the first mission dedicated to making a survey of the chemical composition and thermal structures of up to 1000 transiting exoplanets, bringing a new level of planetary science into the realm of other stars. The mission designers note that while we’ve discovered thousands of exoplanets, we have as yet no pattern that links their masses, sizes and orbital parameters to the nature of the parent star. How is a planet’s chemistry determined by its place of formation, and how does its evolution depend upon the properties of the star it orbits?

The mission will home in on warm and hot planets, ranging from super-Earths to hot Jupiters, to parse the chemistry of their atmospheres as they transit, making a deep survey of cloud systems as well as seasonal and even daily atmospheric variations for a subset of its targets. ARIEL will operate at visible and infrared wavelengths as it orbits the L2 Lagrange point 1.5 million kilometers behind the Earth as viewed from the Sun, with a mission duration of four years.

For more on ARIEL’s target list, see Edwards et al., “An Updated Study of Potential Targets for Ariel,” The Astronomical Journal Vol. 157, No. 6 (30 May 2019). Abstract / preprint.

Golllllll eeeeee, the name “Borisov” is certainly having its 15 minutes of fame, isn’t it? By the way, anybody know if Vadim and Gennady are related in any way, or is it just one of those darn coincidences?

And James Dawson is a well known name in the British Astronomical Association. Different man I assume.

Hi Paul

A very interesting article. If I had the time and Funds this would be my observatory project

Here’s to hoping ??that some citizen scientist or even a rank amateur finds a world-view altering megastructure or some such artifact!

There for a while, I thought they(citizen scientists)already did. However with the possibility of bonafide megastructures having been reduced to nanobotic “magic dust” AT BEST, there still remains a glimmer of hope: The double star system of HD 139139, now known as “The Random Transiter”. We currently do not know which star these objects orbit around. My take is that if they orbit the primary G star, they are most likely an extremely bizarre natural phenomenon(Jean Schneider published a paper on this a couple of days ago that very reluctantly convinced me after months of leaning slightly towards a non-natural solution)BUT: If these objects are found to orbit the secondary star, INSTEAD, all bets are off! To me, bonafide megastructures seem to be the ONLY LOGICAL SOLUTION! Stay Tuned!

Thanks for this article on The ARIEL Data Challenge 2019. I participated in the same and am sharing the blog post on how I went about this challenge.

Predicting Exoplanetary Atmosphere using Machine Learning

https://hotpoprobot.com/2019/09/15/predicting-exoplanetary-atmosphere-using-machine-learning-the-ariel-data-challenge-2019/

Thanks!

Great to have you here, and thanks for the link re the Data Challenge. Much appreciated!

Sometimes It is very good to fail. Unlike K2-18b, astronomers were UNABLE to detect water in the atmosphere of LHS 1140b, implying the probable lack of a super-thick atmosphere, but not putting to rest the possibility of a thick hydrogen/helium depleted Venus-like atmosphere. Thus LHS 1140b should be a prime target for ExoClock prior to the launches of PLATO and Ariel next decade. Hmmmm, I wonder, however if Cheops could detect a Venus-like atmosphere should there be one. I know JWST can, but impatient me would like the answer early next year if possible.

An exoplanet that should not exist – says who?

https://www.unibe.ch/news/media_news/media_relations_e/media_releases/2019/medienmitteilungen_2019/a_planet_that_should_not_exist/index_eng.html

To quote:

Astronomers detected a giant planet orbiting a small star. The planet has much more mass than theoretical models predict. While this surprising discovery was made by a Spanish-German team at an observatory in southern Spain, researchers at the University of Bern studied how the mysterious exoplanet might have formed.

The red dwarf GJ 3512 is located 30 light-years from us. Although the star is only about a tenth of the mass of the Sun, it possesses a giant planet – an unexpected observation. “Around such stars there should only be planets the size of the Earth or somewhat more massive Super-Earths,” says Christoph Mordasini, professor at the University of Bern and member of the National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) PlanetS: “GJ 3512b, however, is a giant planet with a mass about half as big as the one of Jupiter, and thus at least one order of magnitude more massive than the planets predicted by theoretical models for such small stars.”