The Russian space agency Roscosmos, as most of you know, has announced the death of cosmonaut Alexei Leonov, who died last Friday at Moscow’s Burdenko Hospital following a long illness. He was 85.

If handling stress under extreme conditions is a prerequisite for someone who is going to the Moon, Leonov had already proven his mettle when the Soviet Union chose him as the man to pilot its lunar lander to the surface. The failure of the N-1 rocket put an end to that plan, but Leonov will always be associated with the 1965 mission aboard Voskhod 2 shared with Pavel Belyayev. This was the spacewalk mission, conducted successfully before NASA could manage the feat 10 weeks later.

Image: A man and his art. Alexei Leonov was as attracted to drawing and painting as he was to flying, creating some work while in orbit. Credit: Roscosmos.

The problems Leonov had with his bulky spacesuit as it ballooned out of shape are widely known, making his re-entry into the capsule a dicey affair, though one he managed with skilful use of a bleed valve in the suit’s lining. But consider everything else that went wrong: The charge fired to remove the airlock caused Voskhod 2 to tumble, while oxygen levels in the cabin began to rise and took several hours to correct.

Add to this the failure of the automated re-entry system, and the tangled separation of the orbital module from the landing capsule, caused by a communications cable that had failed to separate. It was the heat of re-entry itself that finally burned through the cable and allowed the landing module to bring both cosmonauts home. Then they landed so far downrange from their intended target that two days passed before they could be reached in a taiga forest in the Ural Mountains.

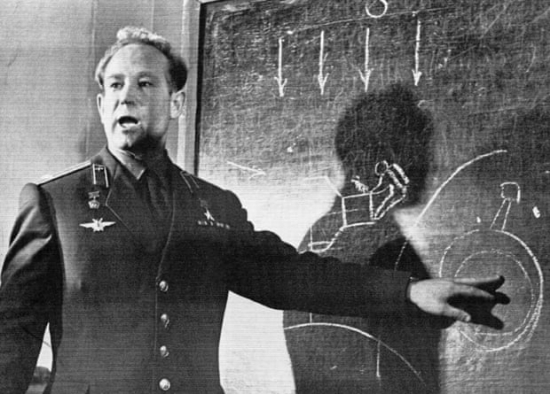

Image: Alexei Leonov in 1965. Credit: Associated Press.

This was indeed the kind of man the Soviet Union would have liked to place on the Moon ahead of the Apollo astronauts, but it was not to be. Leonov, who went on to be given the title of Chief Cosmonaut, is also remembered for the Soyuz he piloted and docked with an Apollo capsule in 1975 in the Apollo Soyuz Test Project, which was the first mission conducted jointly between the US and the Soviet Union. A self-taught artist, Leonov created what as far as I know is humanity’s first artwork in space when he did a colored pencil drawing of a sunrise as seen from Voskhod 2.

Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey included recordings of Leonov’s breathing in space, a great move by a great director, but the later 2010 (directed not by Kubrick but Peter Hyams) would provoke an official response. Twice made Hero of the Soviet Union, but later suspected of disloyalty to the government, Leonov had been brought before the Central Committee of the Communist Party to explain the fact that the spaceship named ‘Leonov’ in the film (nice touch by Clarke) had been filled with Soviet dissidents. Leonov is said to have responded that the committee “was not worth the nail on Arthur C. Clarke’s little finger.”

A quote from Leonov’s Two Sides of the Moon: Our Story of the Cold War Space Race (Thomas Dunne Books, 2004), written with NASA astronaut David Scott, may be the best way to end as we consider how close this man came to being first on the Moon. The time is early 1966, and Soviet Luna probes had completed a series of missions in lunar orbit. Leonov recalls:

I was undergoing intensive training for a lunar mission by this time. In order to focus attention and resources our cosmonaut corps had been divided into two groups. One group, which included Yuri Gagarin and Vladimir Komarov, was training to fly our latest spacecraft — Soyuz — in Earth orbit…

The second group, of which I was commander, was training for circumlunar missions in a modified version of Soyuz known as the L-1, or Zond, and also for lunar-landing missions in another modified Soyuz known as the L-3. Vasily Mishin’s cautious plan called for three circumlunar missions to be carried out with three different two-man crews, one of which would then be chosen to make the first lunar landing.

The initial plan was for me to command the first circumlunar mission, together with Oleg Makarov, in June or July 1967. We then expected to be able to accomplish the first Moon landing — ahead of the Americans — in September 1968.

Alternate histories are fascinating to consider. But no matter which timeline we dwell in, Alexei Leonov was a courageous, generous man who carried the spirit of that insanely adventurous era. It’s a spirit we can strive to recover.

Leonov’s passing reminded me of an incident 20 years ago when I literally bumped into him during one of my business trips to Moscow. While I was reaching for my luggage on the carousel in the international terminal of Moscow’s Sheremetyevo Airport, I accidentally bumped into a Russian gentleman in his mid-60s wearing a uniform who was attempting to get his bag as well. We glanced at each other and briefly excused ourselves while exchanging a smile before getting our respective bags and continuing on our separate ways. Between the lack of sleep after a long overnight flight and being focused on meeting up with others in my group before heading through Russian customs, it took me a half a minute to realize that I recognized that officer: he was the famous Russian cosmonaut, Alexei Leonov. By the time I realized this, Leonov was already beyond customs and moving out of sight so I never had a chance to talk to him – which might have been a good thing considering I had only a couple of hours of sleep and my internal clock was eight hours out of whack. While its wasn’t much of an encounter, I’ll always remember “bumping into” one of the true heroes of the early Space Age.

https://www.drewexmachina.com/2015/03/18/the-mission-of-voskhod-2/

It’s an encounter I would certainly have remembered for the rest of my life. I had a similar situation with Frank Borman. He had just flown one of Eastern’s corporate jets into the airport where I was instructing and he was at our FBO paying for the fuel he was adding to the plane. I noted his craggy profile and incredibly imposing manner, and I thought ‘This is the kind of guy who would get into a completely untested situation and make it happen,’ which of course is what he did. I wished I had had the chance to talk to him but he was quickly out of there, obviously pressed for time.

I had know idea that the N1/L3 was slated for a 67/68 timeline, but the whole history of that program and the great effort the people of the Soviet Union to reach the Moon should be made into a movie.

There is a movie about Leonov’s spacewalk made in Russia called Spacewalker released in 2017 and based on reviews it’s pretty good. Unfortunately it’s not available in the US.

Apple TV+ is making a TV series called “For All Mankind” – it will be interesting to see how they show Leonov’s role in their alternate history of the Soviet’s winning the race to the moon. See https://www.popularmechanics.com/culture/tv/a27703218/for-all-mankind-trailer-apple-tv/ for a trailer.

But it all goes all much further than the moon. I’m looking forward to this one.

According to the book Space Odyssey by Michael Benson, that it was Kubrick himself who did the breathing effects.

Paul, where did you read about Leonov doing those effects? Did they take a recording of the cosmonaut breathing during his EVA in 1965? Would Westerners even have had access to such a recording then? I am guessing Leonov was not invited into Pinewoods Studio.

From the same source, it should be noted that Clarke also got Leonov in a bit of trouble by dedicating the 2010: Odyssey Two novel to both Leonov and Andrei Sakharov, who was quite the Soviet dissident at the time.

https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/Space-Odyssey/Michael-Benson/9781501163944

So many “what if’s”. If Korolev hadn’t died, would the N1 have been successful? If the N1 had been successful, would the soviets have been first on the Moon? And if that happened, would the US have pushed on to Mars, or completely abandoned space and competed in another arena? If the Soviets had been first on the Moon, would that have increased their global standing and their geopolitical position, perhaps even staving off the end of the USSR and continuing the cold war as the first 2 Space Odyssey novels depicted?

No, US will not push to Mars – it’s too expensive and unrealistic. US did very smart moves with Pioneers and Voyagers

Alex, I have sometimes thought that if the Soviets did not cancel their Lunar program, then just possibly that today there would be people on the Moon.

I recall reading that ultimately the Soviets wanted to have a small scientific base there. Whether any kind of base would have been possible is another story. Still I also recall former NASA administrator Thomas Paine stating that the US would not abandon the MOON if the Soviets had any plans for it. On the other hand their Lunar program was canceled in 1974 and I the Saturn V production line ended a few years earlier and there was that commitment to the Space Shuttle.

The 1970s was a time of retrenchment from the heady 1960s boom. The Vietnam War was a huge drain on the US economy and very unpopular. The problems of pollution were stacking up. There was an anti-technology backlash. The US fell of the gold standard when it became untenable to remain on it. It shouldn’t be surprising that Nixon canceled the Apollo program. NASA programs became more Earth focused. Had Russia reached teh Moon first, and could have afforded to a base on the Moon, then it is possible that the US would have done something similar to bolster national prestige. It is also quite possible that Russia would have declared victory and abandoned the Moon too, given its much smaller economy and its own domestic problems.

I fear that we are in another heady boom. Just like the 1960s, companies are jumping on the space bandwagon, there is hype everywhere you look, but few tangible gains. SpaceX has demonstrated reusable 1st stage rockets, but I see only a limited move to reduce launch costs. Maybe in time. Meanwhile, the fanbois are assuming the Starship will fly as advertised and a Martian colony is on the horizon. Is this so different from the suggestion that a modified, “heavy lift” Space Shuttle will facilitate the creation of O’Neill colonies? With another stock market collapse, I suspect these projects will collapse once again. The global heating crisis seems like a replay of the 1970s, albeit with even more urgency and it will have an impact on economic growth. If a concomitant move to reduce inequality succeeds, this will further hamper, if not kill, the SpaceX and Blue Origin programs.

We should have learned by now that unless an activity can be self-sustaining, that is commercially viable, it will be precarious. A Moon base will have to justify itself, and that means that it will have to provide economic reasons to exist. Making rocket fuel for a non-existent space economy just doesn’t cut it. Which is why I think that space will become dominated by the increasing capabilities of small robots. If low-cost launches become viable, then the scientific and commercial possibilities increase. That seems like a more viable path to building up larger commercial systems.

I have to admit Musk’s plans for colonizing Mars sound wild and outlandish. One thousand StarShips to Mars every 26 months until the population there is 1 million people? What would the cost of this enterprise be? Surely in the trillions or tens of trillions of dollars if it was even feasible. The projected timeline is 50 to 100 years. Wildly unlikely to say the least. But one might as well dream big!

The only way space will become viable is a new way to get there. Giant tanks of explosive gas is not my idea of the way to go, unless you have a death wish. But I can fly 8 miles high without a problem – so until the space drive arrives I’m afraid we will be stuck here. The other side of the coin is that almost everyone will be able to go to space if that drive ever happens!

Will a skyhook do? Fly up to the hook and then your craft is hauled up to space as the structure rotates. This does not require advanced materials to work. If the passenger craft fails to make the connection for any reason, it safely flies back down to the ground. Unless the hook is also sending payloads back down to Earth (ET sourced material) there is the issue of maintaining its orbit. But otherwise, this is a doable technology. I would probably build the structure with lunar or asteroid metals to reduce the immense Earth-to-orbit launch costs, but once complete, it would have excellent launch capacity. The major obstable I can see is that it would need a clear path in orbit, or satellites to steer clear. However, the same technology can be used around other planets and moons to reduce launch costs, where satellite constellations are not yet an issue.

The Soviet N-1 rocket was just too unwieldy to work. Not one single flight made it into space: Every single one exploded. Imagine something equivalent to the Saturn 5 exploding multiple times.

I even have doubts about their mission plan. Too many failure points along the way. We just had the 50th anniversary of the Soyuz 6, 7, and 8 mission, which was supposed to have two of the Soyuz dock while the third filmed from the distance, all in Earth orbit. The docking failed, though it was impressive to have three manned ships maneuvering near each other in space.

I am not trying to discredit Soviet space engineering. They did some impressive things in space. I just think they were trying too much in too short a time. A lesson for our current manned lunar plans.

Also Alexey published book for kids in 1980 with his own pictures – that’s how I knew in my 6y about cosmonauts and their risky job in space, but most risky and dangerous moments was omitted of course – it’s kid’s book.

Arthur C. Clarke from time to time would comment on his meetings with Aleksej Leonov which served as an introduction for many of us

who read Clarke’s stories fiction and non. So if we could imagine ourselves sitting at a table and so challenged, here is my personal account.

Back in the summer of 1990, I had the opportunity to meet and talk with Aleksej Leonov a few times. That year caught me interested in Soviet developments in rocket booster engines, continuing to review the Russian I had learned in earlier years, now for a prospect in space I knew not what – and a People to People delegation invitation to explore Soviet and Polish aerospace facilities with a group of engineers and teachers. Since other than the Intourist interpreters I was the only delegate that had previous Russian language training of any length, I was often asked to pick up interpreting tasks and often ready to try my hand. It was something akin to learning to fly. Maybe not as dangerous.

Similar to Mr. LePage above, after two long flights, from Boston and then to Frankfurt, we all arrived groggy in Moscow, shocked by the convergence of everything that had happened to us, including looking at a Looking Glass version of our own society in the wind down of the decades long Cold War. Our first trip off the plane and out of our hotel on Moscow’s south side was a bus ride to Star City, its training center, and the Space Museum. On hand to guide us in our tour were several cosmonauts – among them was Aleksei Leonov with something specific to say. We were sat down and addressed as a group:

The Soviet government was inviting the United States to participate in building a joint space station. P

erhaps it would be a Mir-2. Perhaps it would be something else.

In this guise, this first personal meeting, I came to appreciate Aleksei Leonov as a very persuasive salesman = or statesman. We knew he was serious, but the delegation, in our subsequent discussions would not have bet on the outcome of his proposal. Nonetheless, for more than ten years thereafter, I found myself tied up much of the time with the

International Space Station effort, something that just might have been proposed that day. A succession of Russians and Americans involved in space would transfer back and forth, meeting face to face the design the station orbiting over our heads today. Aside from official meetings, I remember many a meal where I never finished raising a fork or spoon to my mouth because of relating something someone else had said – with questionable fidelity.

In the museum visit, Leonov guided us about the displays with good humor, especially when we were invited to examine his many awards.

At some of the stops, we engaged in some small talk. I would see if I could get off a coherent question or answer in Russian and was delighted with what resulted. It was all like a dream. And it made even space travel seem like a dream within reach – after all. The Soviet Union of my adolescence in which he climbed out of a capsule in an over inflated suit seemed now as remote as Mars, even though in that government’s waning year or so it seemed strange itself. Shaking hands with Leonov was like shaking hands with a fire hydrant. You could see why he might have been selected for that space walk, how he must have trained for it -and how his difficulties with movement were likely anticipated. Inflate a bag to sea level pressure with you in it and put it in a vacuum. Now try to do anything.

The tour had so many impressions it’s hard to describe. But by strange coincidence, shortly after retuning to the US, Houston and the Johnson Space Center, I was making my way back to a parking lot after a meeting and I witnessed a strange procession with the familiar faces

of the Apollo Soyuz astronauts and cosmonauts wandering across a quadrangle shaking hands with passers-by. Fifteenth anniversary of the flight. Leonov remembered my face from the more recent Moscow meeting ( or else he thought I had worked on ASTP) – and I remarked that he should have run for office.

The only Apollo mission I was in Houston and on hand for was Apollo Soyuz – and it was something like a strange encore mixed with an afterward about where we were going to head after that. In that period I was abstaining from TV, but we watched Leonov and Kubasov’s launch on a rental. The public address kept us posted: “Vye rabotayut normal’no…” It sounded like a liturgy as the Soyuz rose through the cloud strata.

The space center and its facilities were very open back then. Johnson, that is. Employees, those still around after the slowdown after Apollo 17, they could easily find access to observation rooms at Building 30 or entry into the wide screen observing areas on the facilities. In fact, after one session where I watched Bruce McCandless ( to be a later free flyer in space), I was buttonholed by a Trud correspondent, who wanted to look at my badge rather than interview me. Like crowds of fellow workers, I watched the opening of the hatch; Stafford, Slayton and Brand on one side, Leonov and Kubasov revealed on the other, welcoming with bread and salt, traditionally, or if I recall correctly.

In the events of August 1991, Leonov shortly disappeared from the public scene for many years. I found myself shaking my head when a British spy melodrama named a cable cutting submarine for him, something imported as a serial on US Public Television. But he was still around. In 2014 here at home we experimented with cable requesting the Russian Kanal 1. It was a roller coaster ride for an American viewer, but I note for one thing, that we caught a broadcast for winners of the Russian Cross of Saint George, previous and that year – and they were all gathered for a palatial dinner in the manner of a professional conference but dressed as though ready for the Emperor to announce the waltz. There at one of the tables was General Leonov in dress uniform, decked with full honors. A delight to see him.

What a remarkable account! Thanks for sharing this, wdk, and how fortunate you are to have had these experiences with Leonov. Fascinating.

Paul Gilster,

Thank you.

Since I hit the submit button, a few more things came to mind such as clarifications and corrections.

Mentioning Bruce McCandless: He was serving as CapCom or capsule communicator on that last Apollo flight. And he was also one of the Apollo astronauts who was yet to fly. Later on in the next few years he was often present, acting perhaps as chair, at the Space Shuttle reviews at JSC for guidance, navigation and control (GN&C). And I remember wondering what an uphill trek it must have been being an astronaut in the late 1970s. Years later after he had flown the MMU untethered from the Shuttle, there were several opportunities to work with him directly. In one instance it was an informal, relaxing assignment involving “architecture studies”, varieties of space systems for NASA to invest in. He was on one contractor team and I was on another. We were all unbiased, of course, about the other six teams’ ideas or else our own. None of us could agree on much of anything, but it was educational and offered frequent interesting lunch or dinner get togethers at the end of the day.

I remember one time when we were on a telecon and I ventured into space mission costs citing the cumulative ones associated with releasing an Edmund’s scientific weather balloon as a radar target for rendezvous tests from the Shuttle payload bay. $400K. I was feeling self satisfied that I had finally contributed something, when the intercom crackled:

“Hey, wait a minute! I was on that flight and I was responsible for that experiment!….” The numbers all made sense to him and he gave me an an accounting on the intercom and then another one to one just for good measure. He turned out to be a good friend from those architecture days on and is sadly missed.

My Russian quote above got garbled somewhat by a missing key strike or so. “Vsye [sistemy ] robatayut normal’no.” would be a little closer to the repeated chatter in ascent: All systems operating/working normally.

Among the souvenirs from that 1990 Soviet trip, there were various purchases at stores: hats, pins, vinyl records, books… (Even a reciprocal visit to the States from the Soviet Council of Ministers advisor on cosmic affairs – our host in Russia and Kazakhstan, but not in Ukraine)… But one of the books I brought back was another “cosmonautics ” artifact from a Moscow Dom Knigi, as the national bookstore chain was called ( House of the Book). It was a Yuri Gagarin commemorative conference, a collection of papers on the first cosmonaut, chaired by Aleksei Leonov along with his introductory comments and essay or two. A lot of the material was about Gagarin’s fateful last jet aircraft training flight. If it turns up in search soon, perhaps there will be something else to add.

By all means, wdk, as any other recollections come to mind, please send them! Much appreciated.