If those of us from the Apollo era sometimes look back with regret at the failure of our society to follow through on early lunar exploration, we can still acknowledge that the issue is far from settled. As Nick Nielsen points out in the essay below, we’re in an interesting period, one in which commercial interests are changing how we look at future space missions, and indeed, changing our view of what may be considered the central project of our civilization. With historical sweep that takes in the death of Socrates, paleolithic art and Arthurian mythology, Nick sees as the great monuments of civilization not just the Pyramids, the Parthenon and the Taj Mahal, but also the Large Hadron Collider and the International Space Station. Here’s a richly textured probe, then, into the mythologies that make us who we are and who we will be, and the forces that shape what a civilization chooses to do.

by J. N. Nielsen

There is a Tide in the affayres of men,

Which taken at the Flood, leades on to Fortune:

Omitted, all the voyage of their life,

Is bound in Shallowes, and in Miseries.

Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, Act IV, scene iii, lines 2217-2220

Brutus to Cassius, before the battle at Philippi

1. Ankle Deep in the Shallows

2. Periodization of the US Space Program

3. Scenarios for Spacefaring Breakout

4. A Stagnant Space Age

5. A Digression on Periodization

6. Institutions and Their Central Projects

7. Institutional Drift in Private Enterprise

8. The Consolation Prize for Institutional Drift

9. How the Space Industry Got Its Groove Back

10. Finding a Compromise That Works

11. Human Purposes in Deep Time

12. Sufficient Conditions for Spacefaring Civilization

13. The Weston Principle

14. The Beginning of the Inquiry

1. Ankle Deep in the Shallows

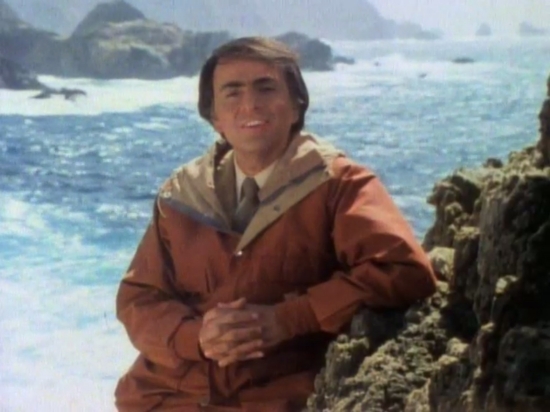

Carl Sagan opened his Cosmos, both the television series and the book, with this reflection:

“The surface of the Earth is the shore of the cosmic ocean. From it we have learned most of what we know. Recently, we have waded a little out to sea, enough to dampen our toes or, at most, wet our ankles. The water seems inviting. The ocean calls. Some part of our being knows this is from where we came. We long to return.” [1]

For Sagan the water seemed inviting, but to continue the metaphor with which Sagan began, if the ocean had called to humanity, we could have continued wading further into the tide, into deeper waters, until eventually we lost our firm footing and, in order to continue, we would have had to swim forward, out into the deeper, darker waters. Instead, we waded out ankle deep with Apollo, but then retreated and now are only keeping our toes damp.

What has happened to space exploration? Why has it faltered from its ambitious and hopeful beginnings to become what it is today? Who is responsible for the contemporary state of space exploration? What can be done about the state of space exploration? Are we to expect more of the same, such as we have seen for the past fifty years, or will there be a revival of space exploration no less ambitious than its initial efflorescence?

Here I am going to attempt to discuss many matters that I have also discussed earlier and elsewhere, but hopefully to bring together some disparate threads so as to see them whole in their social context. While the lens of my discussion will be the US space program and its institutional drift since the Space Race, what I have to say about the US space program applies, mutatis mutandis, to other institutions and their programs. Specifically, what I have to say about the institutional drift of the US space program applies to the institutional drift of other institutions, both larger and smaller than the space program. It applies to larger institutions, such as the largest of all human institutions — civilization (one of my eight definitions of civilization is that civilization is an institution of institutions)—as well as to smaller institutions—say, individual businesses, or particular scientific research programs—both of which, large and small, falter, founder, and fail when purpose is lacking.

2. Periodization of the US Space Program

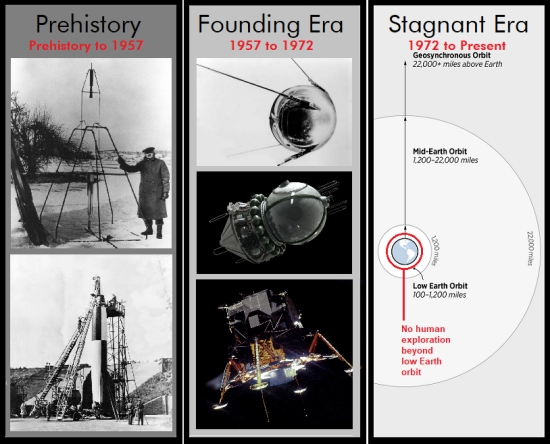

Considered historically, the US space program may be roughly divided into three periods:

1. Prehistory: aviation and aeronautical development leading up to the Sputnik Crisis

2. Founding Era: from the Sputnik Crisis to the Apollo Program

3. Stagnant Era: from the Apollo Program to the present day

The prehistory of the space program can be traced all the way back to the first use of tools by human beings. For any technological development we might identify as the authentic beginning of the aviation and aeronautics, there is another technological development prior to this that could be identified as a prerequisite for the later technological development, so that the identification of any one technological threshold is merely conventional. We can identify conventional historical thresholds if we like—for example, we could identify an immediate predecessor era to the Founding Era that could begin with Robert Godard’s liquid-fueled rocket of 1926, or, before that, with Hermann Oberth’s 1923 book The Rocket into Planetary Space (Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen), or, before that, with Konstantin Tsiolkovsky’s 1903 book Exploration of Outer Space by Means of Rocket Devices (???????????? ??????? ??????????? ??????????? ?????????)—in order to give an earlier bound to a immediate predecessor period. The many possible thresholds for a more narrowly defined prehistory to aerospace technology (narrower, that is, than simply taking the whole of technological prehistory) points to the problem of identifying an authentic origin. There is nothing at all illegitimate about an inquiry into origins, or in formulating a periodization based on such an inquiry, but it is not a problem with which I will concern myself here.

The Founding Era [2] speaks for itself. It begins with an accomplishment, the first artificial satellite, but this accomplishment was not the end of a great effort; rather, Sputnik was the beginning of a great effort, and was immediately followed by further accomplishments building upon the Sputnik success, ultimately culminating in the Apollo moon landings. The Russian space program did not ultimately send cosmonauts beyond low Earth orbit, but the trajectory of the Soviet program could be given a similar periodization to that I have given for the US space program, as during the Space Race the Soviet space program was rapidly advancing in technology and the pace of operations in order to match the US space program, and, given time, might have launched its enormous N1-L3 rocket, rival to the Saturn V, and made its own attempt at a moon landing.

The Stagnant Era, the present era of space exploration, is that period since the end of the Apollo program which has been characterized by a lack of clear purpose, both public and private institutional drift, and a failure to aggressively develop the technologies of space exploration, that is to say, a failure to push the envelope of technological development. (I have earlier discussed the stagnancy and institutional drift of the US space program in A Strategic Pause in the Development of Spacefaring Civilization.) In section 4, below, we will go into much greater detail on the Stagnant Era.

We can postulate a nascent fourth period now underway (a post-Stagnancy Era) during which private space industries may fulfill and expand upon the promise of the Founding Era, though at the present time it is not yet clear if we have emerged from fifty years of space exploration stagnation, or whether the apparent momentum of the present is illusory and will either come to an end in the near future, or it will enter into its own comfortable plateau of stagnation once it passes beyond infancy. I have a theoretical and analytical interest in history, but I am not a prophet, so I will not attempt to predict which fork in the road our civilization will take over the next few decades. (However, my theoretical perspective does not mean that I am without any agenda, and I will make no secret of my preferred outcome.)

One of the remarkable features of the Stagnant Era is that there has been, at least since the 1930s (judging by the science fiction of the period), a clear awareness of the possibility of how space exploration and space industry could transform human life on Earth and lead to a human civilization encompassing and transcending Earth, but, despite the awareness of the vision, that vision alone was insufficient to drive a spacefaring breakout. An active space program, both in terms of crewed missions and space science robotic missions, also has been insufficient to drive a spacefaring breakout. Given that being a space-capable civilization is a necessary condition of spacefaring breakout, this begs the question as to what exactly would constitute a sufficient condition for a spacefaring breakout.

3. Scenarios for Spacefaring Breakout

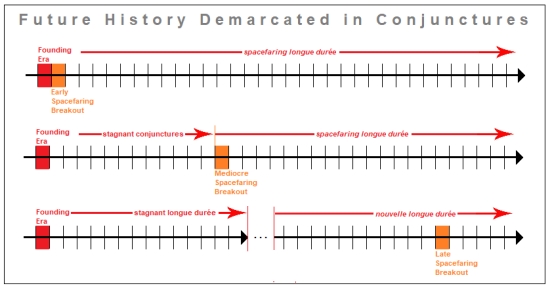

What do I mean by “spacefaring breakout”? In The Spacefaring Inflection Point I distinguished three scenarios for what I call spacefaring breakout, which is when some heretofore exclusively planetary civilization becomes a spacefaring civilization:

• Early Inflection Point: when spacefaring is pursued with exponential scope and scale immediately upon the technology being available.

• Mediocre Inflection Point: when spacefaring is pursued with exponential scope and scale only after it has been available for a substantial period of time, but in the same longue durée period within which the technology became available.

• Late Inflection Point: when spacefaring is pursued with exponential scope and scale only after the technology has been available throughout a longue durée period of history, so that the realization of spacefaring appears in a subsequent longue durée period of history. [3]

To return to our opening metaphor of the cosmic ocean borrowed from Carl Sagan, spacefaring breakout is the moment when we no longer feel the sand beneath our feet, and we must begin to swim if we wish to continue to move forward, rather than to retreat; the transition from wading to swimming is the inflection point. Once you’re swimming in the cosmic ocean, even if you are still in sight of the shore, you are no longer reliant upon this proximity, and the whole of the cosmos is open to the strongest swimmers.

The same transition from planetary to spacefaring civilization can be formulated as the distinction between space-capable civilizations and spacefaring civilizations, a distinction due to Dr. Jim Pass and elaborated in his paper “An Astrosociological Perspective on Space-Capable vs. Spacefaring Societies” Employing Pass’s terminology, spacefaring breakout is the transition from space-capable to spacefaring civilization, and the above schematic trichotomy distinguishes three formulations of this transition as an historical process. A spacefaring breakout is not yet part of human history, but it can be thought of in historical terms, i.e., as an historical process, albeit an historical process that, if it occurs, will occur in the future. However, the process is no less historical for being set in the future.

Making this tripartite distinction in spacefaring breakout makes the question of the previous section—What exactly would constitute a sufficient condition of a spacefaring breakout?—three distinct questions:

• What could constitute a sufficient condition of an early spacefaring inflection point?

• What could constitute a sufficient condition of a mediocre spacefaring inflection point?

• What could constitute a sufficient condition of a late spacefaring inflection point?

In each of the above questions, the necessary condition of a spacefaring breakout, whether early, mediocre, or late, is the same: being a space-capable civilization. For a sufficient condition, there may be a single response that answers all three questions, or there may be a distinct answer for each distinct historical process representing spacefaring breakout, accordingly as the distinct stage of development at which a civilization finds itself as it faces the question of launching a new Age of Discovery in space—or not.

4. A Stagnant Space Age

During the Founding Era it seemed as though the space exploration vision was about to be realized, and it was in fact partially realized, but after fifteen exciting years of the Space Race, the initial efflorescence of the space program faded, and subsequent space exploration confined itself within less ambitious horizons. If the Founding Era had been the historical point of origin for spacefaring breakout, human civilization would have experienced an early spacefaring inflection point. [4]

The Space Race was a superpower competition by proxy, and was not about achieving a spacefaring inflection point, although the two seemed to coincide for a time. Instead of (or, perhaps I should say, in addition to) fighting each other on proxy battlefields of the Cold War, the US and the USSR fought for supremacy in space: “The US and USSR utilized the space fight and planetary exploration programs as an assertion of superiority. What made this conflict extraordinary was the fact that it was a nonviolent war.” [5] While prominent intellectuals like Bertrand Russell expressed their contempt for the superpower competition aspect of space exploration [6], there is an important sense in which the Space Race represented the best of humanity, when our destructive drive for warfare was sublimated into achievements in science, technology, and engineering. [7]

The Stagnant Era began when superpower competition reverted to less imaginative, more conventional forms of proxy warfare, but a counterfactual in which the Space Race form of superpower competition continued is far from inconceivable. Indeed, space artist Mac Rebisz, in Space That Never Was, illustrates just such a counterfactual. Rebisz writes of his artistic vision, “Imagine a world where Space Race has not ended. Where space agencies were funded a lot better than military. Where private space companies emerged and accelerated development of space industry. Where people never stopped dreaming big and aiming high.”

After fifty years of the Stagnant Era, a spacefaring breakout even in the near future would constitute a mediocre spacefaring inflection point (which would exemplify the principle of mediocrity and thus would seem more intrinsically plausible than an early inflection point). If no spacefaring breakout occurs for some time, the best that can be hoped for is a late spacefaring inflection point (if any breakout is to occur at all), though we can’t say, apart from other contingent historical circumstances not known to us, how long the present stage of development can be extended before it spills over into a new period of history.

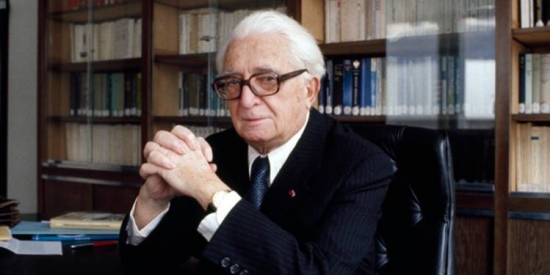

In his Civilisation: A Personal View, Kenneth Clarke noted that, “Great movements in the arts, like revolutions, don’t last for more than about fifteen years.” [8] In so saying, he might well have been speaking of the Founding Era of space exploration, a revolution through which he had just lived as he spoke these lines. [9] Clark also noted in the same book, “People sometimes wonder why the Renaissance Italians, with their intelligent curiosity, didn’t make more of a contribution to the history of thought. The reason is that the most profound thought of the time was not expressed in words, but in visual imagery.” (p. 126) In the same spirit, it would be reasonable to say that the most advanced thought of our time is expressed in science, technology, and engineering, and that great movements in science, or in technology, or in engineering, don’t last for more than fifteen years. Perhaps no one should have expected anything more than this initial efflorescence of the dawning Space Age.

In identifying the period since the end of the Apollo Program as the Stagnant Era, I do not mean to say that nothing of significance has been done by the space program. I have many times pointed out that the space science missions NASA has mounted since the end of the Apollo program have transformed our knowledge of cosmology, and have done so at a relatively low cost in comparison to much “big science.” [10] Judged by the magnitude of the knowledge acquired, these space science missions may have been the best money human beings have ever spent. But expanding our knowledge of the cosmos, while admirable and scientifically exciting, is not going to transform our terrestrial civilization into a spacefaring civilization.

A mature planetary civilization needs to extend itself a little beyond its planetary surface, as homeworld observation is and will be a crucial part of managing a planetary biosphere over the longue durée, but such a civilization could limit itself to operations in a low orbit and still achieve the necessary observational evidence gathered by satellites—much as we have maintained a de facto limitation on human space exploration within low Earth orbit throughout the Stagnant Era. In other words, a mature, long-lived civilization is consistent with a space-capable civilization that never experiences a spacefaring breakout.

I have repeatedly encountered a number of arguments intended to explain, excuse, rationalize, or otherwise justify the stagnation of the Stagnant Era, and I understand why these arguments are made. There are expressions of the inevitability of robotic space exploration (it’s not inevitable and it’s not the same as human space exploration); that human exploration isn’t necessary because machines can do it better (the argument for space exploration isn’t from its necessity) and it would be dangerous for human beings anyway (not everyone is risk averse; some individuals seek out risk) [11]; that Apollo and similar programs were too expensive (there is no economic study that demonstrates that expenditures on the Apollo Program adversely impacted the US economy), and so on and so forth. While each individual rationale for the failure of human space exploration can be argued in its own right and on its own merits, the fact of multiple rationales for this stagnation, such that as soon as we have dismissed one, another is offered in its place, is also significant. I have called this serial excuse-making The Waiting Gambit: if we will just wait, things will be better. There will be a right time for space exploration, but that time is not now.

For those who have never lost sight of the space exploration vision, it is painful to fully accept and to internalize the fact that we have possessed the economic and technological and scientific resources necessary to a spacefaring civilization, but have simply failed as a species to pursue this opportunity. [12] One way to reconcile oneself to this painful state of affairs is to make excuses to justify this failure, but I find it both more interesting and more instructive to face the failure head-on and to try to understand it for what it is. That is what I am trying to do here.

5. A Digression on Periodization

There is a term for the duration that usually characterizes great movements and revolutions (which is what the Founding Era was), as Clark humanistically described them, and that is Fernand Braudel’s term conjuncture. Braudel distinguished three kinds of history:

“…time may be divided into different time-scales and thus made more manageable. One can look at the long or the very long-term; the various rates of medium-term change (which will be known in this book as the conjuncture); and the rapid movement of very short-term developments—the shortest usually being the easiest to detect.” [13]

Braudel also touched on these terms in the Glossary to his The Identity of France:

longue durée, la: literally ‘the long term,’ an expression drawing attention to long-term structures and realities in history, as distinct from medium term factors or trends (la conjuncture) and short-term events (l’évènement) [14]

Richard Mayne, in his Translator’s Introduction to Braudel’s A History of Civilizations, argued that Braudel had arrived at his tripartite levels of periodization as a response to the problem posed by the relationship between, and the concurrent exhibition of, the immediacy and drama of history as it transpires before our eyes, and the silent background to these events which changes little but constitutes the context that makes the passing spectacle meaningful and comprehensible. Mayne described Braudel’s three nested periodizations intended to address this problem in the following terms:

“…the quasi-immobile time of structures and traditions (la longue durée); the intermediate scale of ‘conjunctures,’ rarely longer than a few generations; and the rapid time-scale of events.” [15]

Braudel deemphasizes the history of the event, and Braudel’s revaluation (and indeed devaluation) of the event is the occasion of a quote from Braudel that is poignantly instructive for his conception of history:

“Events are the ephemera of history; they pass across its stage like fireflies, hardly glimpsed before they settle back into darkness and as often as not into oblivion.” [16]

Intuitive and naïve historiography—if there is such a thing, which we might also call folk historiography — privileges the event, much as it privileges narrative. A narrative usually takes the form of a succession of events, often succeeding one another at a rapid pace:

“All historical work is concerned with breaking down time past, choosing among its chronological realities according to more or less conscious preferences and exclusions. Traditional history, with its concern for the short time span, for the individual and the event, has long accustomed us to the headlong, dramatic, breathless rush of its narrative.” [17]

Both the Founding Era and the Stagnant Era can be considered historical conjunctures in Braudel’s sense, and both conjunctures fall within the longue durée of industrialized civilization, which is less than three hundred years old. A space exploration mission like the Voyager Program, which has endured for decades, constitutes its own conjuncture. In the popular media, however, it is the event that is noted and celebrated, torn from the context of its conjuncture and its longue durée. Voyager 2 was in the news a year ago (cf. NASA’s Voyager 2 Probe Enters Interstellar Space, 10 December 2018) because it had passed out of the Solar System, as Voyager 1 had earlier, in 2012. This was an event, and, as Braudel said, it has passed across the stage like a firefly, hardly glimpsed before its settles back into darkness and eventually into oblivion. For space exploration to be more than an ephemeral sequence of events, to be something more than a headlong, dramatic, breathless rush of narrative, it needs to be more than an event; it needs to be recognized as an age in which we find ourselves — the Space Age, a space exploration conjuncture, or the longue durée of industrialized civilization converging upon and transforming itself into a spacefaring civilization.

One way to do this is to begin thinking about space exploration in terms of the longue durée, and, following Braudel, placing less emphasis upon the event. I have already invoked the longue durée in defining spacefaring inflection points; this use of Braudelian periodizations can be made more thorough, as in the following:

• Early Inflection Point: when spacefaring is pursued with exponential scope and scale as a continuous sequence of events, so that the immediate prehistory conjuncture to space exploration is followed by the Founding Era conjuncture, and the Founding Era conjuncture is followed by a further conjuncture that builds upon the Founding Era. This sequence of conjunctures, in turn, begins to define a spacefaring longue durée.

• Mediocre Inflection Point: when spacefaring is pursued with exponential scope and scale only after the Founding Era conjuncture is followed by several further conjunctures, some of them tightly-coupled with the Founding Era and some only loosely-coupled with the Founding Era, but the sequence of conjunctures eventually leads to a spacefaring breakout conjuncture within the same longue durée period within which the technology became available.

• Late Inflection Point: when spacefaring is pursued with exponential scope and scale only after the technology has been available throughout a longue durée period of history, so that a spacefaring breakout appears in a subsequent longue durée period of history. In this way, the Founding Era is the culminating conjuncture for space technologies within a given longue durée, and after lapsing for a time, the next spacefaring conjuncture occurs in the next longue durée. It is possible that this historical rhythm might be iterated several times over before a spacefaring breakout occurs as a result of one of these spacefaring conjunctures.

The justification for thinking historically about spacefaring civilization is to employ the conceptual resources of historiography to analyze and thus to clarify our relationship to historical time, even if this historical time constitutes a period we have not yet completed, or not yet even entered. Arguably, we are not yet a spacefaring civilization, even if we are space-capable civilization, but we can think historically about potential developments, regardless of whether they come to pass.

6. Institutions and their Central Projects

The Stagnant Era, although a conjuncture of space exploration by a space-capable civilization, has been, and continues to be, characterized by the institutional drift of the space program, which latter drift has been the result of a lack of purpose. I have taken to calling the purpose of an institution its central project, having adapted this from Frank White’s The Overview Effect, in which he wrote:

“Since beginning the Overview Project, I have come to see space exploration as part of a long tradition of central projects… These projects, although involving visible material artifacts, were actually vehicles for more abstract social and psychological aims.” [18]

Human beings have created and participated in institutions large and small, and of a bewildering variety, and one of the lenses we can employ in an analysis of these institutions that have governed human social life is that of the central projects of these institutions. Despite the eponymous centrality of central institutions, it is not always easy to identify the central project of an institution, and sometimes it is downright difficult to do so. In Plato’s Republic, Socrates suggests discussing justice in relation to the state rather than justice in relation to the individual because it should be easier, he says, to see justice writ large as embodied in a just state, but this Socratic conceit does not seem to apply to the study of central projects, as the largest institution that human beings have created is civilization, and correctly identifying the central project of a civilization is often difficult, despite (or perhaps because of) the scope and scale of civilizations and their central projects.

Human communities, whether small and temporary or large and long-lasting, have coalesced around common purposes; purposes are the focus of a social group, the force that binds individuals together, and the seed from which civilizations grow into the largest common purposes that have yet emerged among human beings. These purposes begin as something small, parochial, mute, and inarticulate, but over historical time grow and adapt to become something great, cosmopolitan, eloquent, and meticulously, carefully, and explicitly articulated in the creeds and founding documents of a social tradition.

But even as great purposes grow into civilizations that unify the efforts of millions of individuals, there continue to be smaller institutions with smaller purposes, and the space programs of the various space-capable nation-states exemplify these smaller purposes. The US space program after the Sputnik Crisis [19] had a clearly articulated and easily understood goal: beat the Russians in the Space Race, which efforts were given a concrete direction by President Kennedy in 1961:

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.” [20]

The goal was further elaborated in a speech at Rice Stadium in 1962 (the “Moon Speech”):

“We choose to go to the moon. We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard, because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one which we intend to win, and the others, too. It is for these reasons that I regard the decision last year to shift our efforts in space from low to high gear as among the most important decisions that will be made during my incumbency in the office of the Presidency.” [21]

Despite the ultimate success of the Apollo program and the clear purpose that it represented, or perhaps because of the success of the Apollo program and the purpose it represented, once that limited purpose was fulfilled, the space program of the Space Race vanished once the race had been won. For reasons related to this, John M. Logdson called Apollo a dead-end:

“Apollo turned out to be a dead-end undertaking in terms of human travel beyond the immediate vicinity of this planet; no human has left Earth orbit since the last Apollo mission in December 1972. Most of the Apollo hardware and associated capabilities, particularly the magnificent but very expensive Saturn V launcher, quickly became museum exhibits to remind us, soon after the fact, of what once had been done.” [22]

However, a few sentences further along Logsdon adds:

“In 1969 and 1970, even as the initial lunar landing missions were taking place, the White House canceled the final three planned trips to the Moon. President Richard Nixon had no stomach for what NASA proposed: a major post-Apollo program aimed at building a large space station in preparation for eventual (in the 1980s!) human missions to Mars.”

Apollo was a dead-end in so far as it was not followed by additional missions of a similar scale, but this was due to lack of political leadership and unwillingness to fund the vision, not due to any lack of a space exploration vision. The purposes for an ongoing space program were clearly articulated, but these purposes did not enjoy the spontaneous acclaim of the social body. If the additional flights to the moon had gone forward—obviously, the technology and infrastructure was all in place to do this—we would have continued to learn about conducting a space program at the scale of Apollo, and these lessons would have been applied forward to any plan that was funded to continue the momentum established by Apollo. This would have been the time to ride the flood tide to spacefaring fortune; instead, we omitted the flood tide are now bound in shallows and in misery.

For anyone with even a passing familiarity with plans for space exploration, the big picture context for the Apollo Program was the Wernher von Braun mission architecture so memorably laid out in Collier’s magazine (and thus sometimes called the “Collier’s Space Program”) from 1952 to 1954 (years before Sputnik). [23] The Space Shuttle, which was built, was a small fragment of this program, the Integrated Program Plan (IPP) [24]—it was a spacecraft without a mission, because the other parts of the IPP, which would have functioned integrally with the Space Shuttle, were not built. In this sense, the Space Shuttle was a poignant reminder of a lost opportunity (no less than Saturn V launchers, already transformed into museum exhibits, as Logsdon observed), rather than the triumph it was presented as being at the time.

We see, then, that there was a clear vision for the continuation of the US Space Program that would have involved ongoing achievements in space exploration, and moreover that this vision was given an explicit formulation by NASA with its IPP, and before that by Wernher von Braun and other space exploration visionaries. In short, if someone tries to tell you that no one knew what to do next after Apollo, that there were no purposes for the space program once the Space Race had been won, they are simply gaslighting you; there is ample evidence to the contrary.

Within just a few years of the end of the Apollo Program, Gerard K. O’Neill saw the failure to continue to fund the US Space Program at levels commensurate with the Apollo Program as the key problem, and in response to the funding crisis outlined an ambitious space program that would fund itself through solar power satellites (SPS) beaming energy back to Earth. The SPS space program was, if anything, even larger than the von Braun IPP, and involved even greater spaceflight infrastructure, but while O’Neill’s vision was consistent with space exploration, the raison d’être of the O’Neill SPS program was not space exploration per se, but space industrialization. There is a difference of tone, and a difference in rationale, between a space exploration program and a space industrialization program, though a space industrialization program would eventually be exapted for space exploration. Thus while O’Neill’s was a distinct vision of a spacefaring future, and a different purpose for the space program, it was explicitly articulated and constitutes evidence of a multiplicity of space program goals, any one of which would have meant a post-Founding Era distinct from the Stagnant Era.

Even a series of “flags and footprints” missions throughout the solar system, however narrowly conceived, but always leaving flag and footprints at some further remove from Earth, would have both contributed to experience in human spacefaring (meaning experience in the optimal use of available technologies and practical feedback on these technologies that could lead to their incremental improvement) and would have involved the development of a spacefaring infrastructure beyond that which we possess today. [25]

For example, the von Braun space program was focused on a mission to Mars, but that mission to Mars would have entailed all of the elements of the IPP—space shuttle, cislunar shuttle, space tug, nuclear shuttle, low Earth orbit space station, geosynchronous orbit space station, Lunar orbit station, Lunar surface base, and Mars base, with many of these elements assembled in Earth orbit and so providing experience in space-based construction—thus a considerable spacefaring infrastructure. It is at least arguable that, to accomplish a Mars “flags and footprints” mission with the technology known to von Braun, all of this infrastructure would be necessary, whereas the “Mars Direct” mission architecture of Zubrin has been made possible by technologies developed later.

7. Institutional Drift in Private Enterprise

The national space program began to drift when it was essentially defunded by the Nixon administration, and NASA lacked the money to carry out the plans that it had on the drawing board, but the institutional drift of the US space program went beyond government institutions. The largest aerospace contractors that made the US space program possible also began to drift after the Apollo Program, but their drift was, paradoxically, not due to a lack of money, but rather due to a superfluity of money that was made available to them through government programs that had gone adrift: here it seems that institutional drift at the national scale flowed downstream to contractors.

In its time, Boeing did a lot of visionary work, as in the 1968 Integrated Manned Interplanetary Spacecraft Concept Definition, Final Report (in six volumes — Vol. I, Vol. II, Vol. III part 1, Vol. III part 2, Vol. IV, Vol. V, Vol. VI), which is a model for a clearly and explicitly articulated vision, i.e., a very “nuts and bolts” vision in which engineering detail predominates over everything else. But at some point in the subsequent decades, Boeing lost its way. The widely discussed article in The New Republic, Crash Course: How Boeing’s Managerial Revolution Created the 737 MAX Disaster by Maureen Tkacik, demonstrates in a wider context how Boeing lost its way by focusing on its stock price rather than on its products. This is another way of saying that Boeing’s central project, once clearly defined by the engineering challenges of aerospace innovation, drifted away from this focus and was captured by financial interests, which is the common fate of institutions in a condition of drift: when they cease to aspire to an ideal, they tend to the lowest common denominator.

In any large institution—whether an aerospace contractor or a government or an educational system, etc.—there will always be a variety of human types employed. There will, of course, be those who are true believers in the mission of the institution, but this isn’t necessarily the largest part of the staff. Large enterprises mean that many people are brought into a project who have only a peripheral interest in the central project. There will be some within the institution who are mere time-servers, waiting until retirement so that they can collect a comfortable pension. There will be some managers and administrators who are only involved in order to further their careers. There will be those who will get by with as little work as possible. And there will be those who see their duty as being that of making their institution the most successful institution that it can be, but, since they don’t understand or appreciate the central project, their understanding of institutional success is in terms of conventional measures of profit, career advancement, and market share.

This is not to throw shade on the employees of large aerospace contractors and their motivation and commitment; the problems with large institutions are systemic, and not the fault of individuals. I have no doubt that in the Mongol’s Golden Horde there were probably a good number of mediocre horsemen who were not made of the same stuff as those horsemen who achieved decisive victories against the Hungarians at the Battle of Mohi and against the Seljuks at the Battle of Köse Da?. [26]

It is entirely possible for a given business enterprise to be wildly successful in conventional metrics while failing to fulfill the central project that was its raison d’être when the business was founded. It is also entirely possible that a given business enterprise is founded with the intention of making a profit and advancing the careers of its employees, and only becomes attached to some central project for contingent historical reasons that have no intrinsic relationship to the business enterprise in question. This, again, is a function of size. A very large project like the Apollo Program involved numerous contractors, and it would be unrealistic to expect that all of these contractors were as committed to the mission as those who conceived the vision. That doesn’t mean that these contractors weren’t committed to the mission, only that doing great work on the mission was a means to an end, and not an end in itself.

8. The Consolation Prize for Institutional Drift

I am not unaware that, in an age of technology-driven warfare, a nation-state must spend liberally on its aerospace industry in order to ensure that it possesses the technology and expertise to compete as a peer in the contest for air superiority, and that such liberal spending on defense-related industries will inevitably result in a certain amount of waste and corruption, but the waste is often the price of keeping these industries afloat. However, subsidizing industries crucial to national defense is in no sense inconsistent with a strong sense of purpose, and indeed I would argue that an aerospace industry subsidized by space exploration missions that further the central project of a space program would be more effective subsidies and, more, would lead to greater innovation and capability than the kind of lazy subsidy we see with rewarding contractors cost overruns on unimaginative projects that fulfill the letter, but not the spirit, of the tender.

The uncomfortable scenario that we must consider is that, once the space program was gutted by Nixon administration budget cuts, the blow to morale, both at NASA and among its contractors, led to individuals shifting their focus from the central project of the space program to personal and private pursuits that would not be derailed by government decisions. Careerism can, for some, fill the void created when a larger purpose fails. And so it was that the money continued to flow to the space program, which funds were insufficient to mount a space exploration program at scale, but more than sufficient to pay salaries and bonuses. (Boeing CEO Dennis Muilenburg declined his bonuses for 2019 due to the 737 MAX debacle, but in 2018 pocketed $23.4 million in bonuses and equity awards.) The purpose evaporated but careers continued for the lucky few.

The loss of purpose and consequent institutional drift is not merely a loss of meaning and value, but also a financial loss. A spacefaring breakout at an earlier inflection point would have made Boeing one of the largest companies in the world, with an assured future for as long as it participated in this effort. (Boeing is the largest aerospace and defense contractor in the world, but it is not in the top fifty of the largest companies in the world by revenue.) The rewards of following through on the IPP would have been far greater than Boeing receiving an additional 287 million on the CST-100 Starliner fixed price contract (cf. Boeing seems upset with NASA’s inspector general by Eric Berger). I am reminded of when, in the film Casablanca, Rick Blaine insists that he was well paid for running guns to Ethiopia and fighting for the Loyalists in Spain, police captain Louis Renault says to Rick, “The winning side would have paid you much more.” So too, in economics at the scale of the nation-state, or even at a planetary scale, being on the winning side of history pays much greater dividends than being on the losing side, however successful one is at losing. And, unfortunately, receiving government largesse on the CST-100 Starliner (tested, not entirely successfully, for the first time on Friday 20 December 2019) is just an elaborate way of losing.

9. How the Space Industry Got Its Groove Back

The comfortable and profitable relationship that major aerospace contractors have with government institutions could have continued for decades (as it had been going on for decades), or even for centuries, with enormous quantities of taxpayer money spent, and progress in the programs so incremental as to be indistinguishable from stagnation, had it not been for the disruptive entry of private space companies into the aerospace industry and the work of private industry on reusable rockets. [27] NASA, of course, pursued reusable spacecraft with the Space Shuttle, but this well-intentioned exercise took place within an institutional context that virtually guaranteed that few costs savings would be realized from reusability at this scale. There will come a time when reusable spacecraft at the scale of the Space Shuttle will be built and used again, but the economics of large reusable spacecraft will be very different from the economics of the space shuttle; reusability looks different now than it looked when the Space Shuttle was being designed.

The development of reusable rockets by private companies is a game changer not only because of the technology, which may deliver lower costs for access to space, but also because the private companies involved appear to be interested in space exploration as an end in itself, and not merely as a way to profit from government contracts. [28] This is disruptive of the status quo, which had continued to do space business, but had ceased to believe in the mission, for all practical purposes. The fact that this lack of purpose was rarely discussed in explicit terms, but was rather accepted as the background to business as usual, is further evidence of the stagnation of the aerospace industry.

The problem with transcending the status quo and allowing (or even facilitating) a great disruption to shift the direction of history (as would have been the case with an early inflection point for spacefaring civilization), is that no one really knows who will be in power, and who will get the rewards, after the shift has been accomplished. Those who are now in power, and who now receive those rewards that can be conveyed by historical business-as-usual, have a vested interest in not allowing a revolution to occur that would displace them from their position of preeminence.

During the Space Race, the explicitly stated purposes of the competing parties, the US and the USSR, provided a larger framework within which the uncertainties of the great disruption of a spacefaring breakout were moderated. To compete in the Space Race was to be in the vanguard of history, and to win meant that the social system of the winning party to the race would be iterated beyond Earth. Thus the participants in the Space Race—nation-states, national space programs, their contractors, and the contractor’s employees—knew that the revolutionary disruption they were effecting by engaging in the Space Race would benefit their side, which would either directly or indirectly mean a benefit for themselves

It could be argued that the rise of global capital and transnational industry had to rise to a level comparable to superpower competition before a similar degree of certainty would obtain that those in positions of power would continue to hang on to their positions of power despite any disruptive change on a civilizational scale. This is not the only interpretation that can be given to the emergence of private space industries that have disrupted business-as-usual among national space programs, but it is, I think, a plausible interpretation. (Let me know if you have a better interpretation.) Commercial disruption of business-as-usual becomes an acceptable option when the captains of industry are confident that they will be winners in any likely outcome.

10. Finding a Compromise That Works

The institutional drift of the Stagnant Era has been the cumulative result of the sheer size of the institutions involved and the inevitable weakening of the intensity of the space exploration vision. The space exploration vision itself has passed on from its “gee-whiz” Golden Age of Science Fiction origins and entered into popular culture, which means that an originally heroic and inspiring idea came to be lampooned, ridiculed, mocked, and exposed to every kind of jibe and jeer.

There are some interesting parallels to this in history. Socrates was one of the most respected men in Greece, an inspiring figure to many, but that didn’t save him when the Athenians turned against him. There is a fascinatingly well-expressed passage in the ancient historian Eunapius that describes how Aristophanes’ play The Clouds prepared the Athenians for the trial and execution of Socrates:

“. . . no one of all the Athenians, even though they were a democracy, would have ventured on that accusation and indictment of one whom all the Athenians regarded as a walking image of wisdom, had it not been that in the drunkenness, insanity, and license of the Dionysia and the night festival, when light laughter and careless and dangerous emotions are discovered among men, Aristophanes first introduced ridicule into their corrupted minds, and by setting dances upon the stage won over the audience to his views . . .” [29]

Eunapius was willing to go even farther in his condemnation of the Athenians:

“. . . and so the death of one man brought misfortune on the whole state. For if one reckons from the date of Socrates’ violent death, we may conclude that after it nothing brilliant was ever again achieved by the Athenians, but the city gradually decayed and because of her decay the whole of Greece was ruined along with her.” (op. cit., p. 383)

For reasons related to this, traditional cultures have always carefully erected a veil of sacredness [30] around the mythological central projects that have been the core of all civilizations: by shielding their mythological central project from the ordinary business of life, by separating it and treating it as something fundamentally distinct, to be shown deference regardless of context, and by ensuring that a high price is paid for the violation of this taboo, the mythological central project never enters into predictable trajectory of popular culture, hence never becomes the fashion, hence never goes out of fashion, and never experiences the ups and downs of the wheel of fortune (or, if it does experience them, it experiences this variability of fortune to a greatly attenuated extent).

Socrates was admired and perhaps loved, but he (and his philosophical project) was not sufficiently embedded within the Athenian central project that the veil of sacredness protected him from the light laughter and careless and dangerous emotions that led the Athenians to sentence him to death for impiety. Indeed, the veil of sacredness shrouded the piety against which Socrates was said to have offended. For all that the Greeks achieved in philosophy, philosophy was not the central project of ancient Greek civilization. As I have observed above, it can be surprisingly difficult to discern the central project of a civilization; what appears on the surface to be important may in fact be peripheral, while that which appears peripheral may be the true center.

If a mythology of a central project is to endure for the longue durée, it must be inviolate by convention and consensus, or nearly so. To remain inviolate by convention and consensus is as much as to say that the implicit social contract recognizes limits upon the ordinary business of life, exempting the central project from the kind of rough handling that would call into question the foundation of the community that has this central project as its raison d’être.

It probably is no longer possible for the central projects of civilizations since the Enlightenment to maintain the kind of aura that surrounded the religious central projects of traditional civilizations, but that doesn’t mean that industrialized civilizations are necessarily and inevitably subject to drift. [31] It may be possible that an historical narrative could be constructed in such a way as to justify the raison d’être of a community, and sufficiently held apart from other aspects of life so as to be retained more-or-less intact over historical time. That is to say, actual historical events (like the Founding Era) could be mythologized for a social purpose.

We have seen something like this with the foundation of the US, which is an artifact of the Enlightenment—a nation-state explicitly constituted on Enlightenment principles—such that the Declaration of the Independence, the Constitution, and the Founding Fathers have been sufficiently reverenced to retain the cohesion, continuity, and coherency of the Enlightenment project that is the US. We do not yet know how long this compromise can be sustained, nor whether it will ultimately be successful, but it is the most successful project to emerge to date from the Enlightenment. If the Founding Era were to be mythologized in this way, that is to say, in a way consistent with the Enlightenment (and one could easily argue that this is already underway), the cohesion, continuity, and coherence of the Space Age might be similarly retained over historical time. [32]

11. Human Purposes in Deep Time

We have seen that there have been several explicitly articulated space exploration visions that preceded (Collier’s), coincided with (IPP), or followed immediately after (O’Neill SPS) the Founding Era. However, none of these visions were realized except in the most fragmentary form. I have paid particular attention to these explicitly articulated visions simply to forestall claims that there were no such visions to serve as a purpose for an ongoing space program to fulfill, but the explicitly articulated visions are rarely as powerful as those which remain implicit and which are spontaneously expressed within a given social group.

A purpose does not need to be clearly articulated; it need not even be formulated in language. The most effective purposes are those that are tacitly shared by every member of a society, so that agreement on purpose is spontaneous and unquestioned. In small bands of hunter-gathers (i.e., during the bulk of human history, which was also our environment of evolutionary adaptedness), shared purpose is nothing less than and nothing more than survival and reproduction. In other words, the earliest human purposes were the imperatives of natural selection, which functions by differential survival and differential reproduction. As human groups became larger and better organized, growing in scope and scale, purposes became more complex and more abstract, evolving and adapting as the growing society evolves and adapts to its available niche.

When language emerges, and when human beings are sufficiently long-lived that grandparents can pass down the lore of the tribe to grandchildren, while their parents are out hunting and gathering, a tradition and a culture emerges, and later when written language is invented, this culture can be preserved in a nearly pristine state from the inevitable variations that enter into the oral transmission of culture.

This process has been playing out for hundreds of thousands of years, and for millions of years if we extend the scope of our inquiry to include human ancestors prior to Homo sapiens. We have had cities and settled agriculture for ten thousand years (written language appeared approximately half way through this ten thousand year development of settled human societies), while industrialized civilization is less than three hundred years old—in other words, the human world that we know is very recent, even shallow, though human history is much longer than we usually recognize. Because of this deep human history, later developments unusually include survivals from earlier stages of development that have been sedimented into contemporary institutions. [33]

The deepest layer of sedimentation is evolutionary psychology, shaped by our environment of evolutionary adaptedness, and that is why I touched on these deep sources of mythology in my Spacefaring Mythologies post. After the layers of evolutionary psychology come the layers of past human cultures and societies, built upon the earlier evolutionary psychology, and providing the foundation for later cultures and societies long after the earlier iterations have been forgotten, often entirely effaced from the historical record. As social evolution is more rapid than biological evolution, our hundred thousand years or more of social evolution has left us with a deep history of which we are scarcely aware—layers upon layers of sedimented traditions—though I should point out that social evolution can be pushed much further back into prehistory than the human condition extends; we inherit social instincts with our neurological structures that go back in time at least a half billion years. [34]

The most successful mythologies, even the mythologies of sophisticated civilizations, are at least consistent with this deep evolutionary past of the human mind. Mythology is a kind of recapitulation in which the contributions of ages past—whether biological, psychological, social, or cultural—are each given their due, and these antecedents serve as a springboard to something authentically novel, something unprecedented that facilitates human beings to transcend their past and to accomplish something unprecedented. And this is precisely what will be required of a spacefaring mythology: while maintaining some connection to past traditions, something essentially novel must be superadded in order to provide an adequate framework for the novel activities of spacefaring.

If a human civilization beyond Earth ever comes into being, this will be unprecedented in any historical context we might care to invoke—unprecedented in recorded history, unprecedented in human history, unprecedented in terrestrial history, and so on. There have been many human civilizations, but all of these civilizations have arisen and developed on the surface of Earth, so that a civilization that arises or develops away from the surface of Earth would be unprecedented and in this sense absolutely novel even if the institutional structure of a spacefaring civilization were the same as the institutional structure of every civilization that has existed on Earth. For this civilizational novelty, some human novelty is a prerequisite, and this human novelty will be expressed in the mythology that motivates and sustains a spacefaring civilization.

12. Sufficient Conditions for Spacefaring Civilization

A spacefaring civilization (or what I have called a properly spacefaring civilization, i.e., a civilization that takes spacefaring as its central project) requires a spacefaring mythology, and while a spacefaring mythology would be an unprecedented development in human history, it cannot appear de novo. Any mythology, in order to be viable, must draw from the same human materials as all previous mythologies, which is to say, a viable mythology must draw from the deep past of sedimented traditions that we carry both within ourselves and in our cultures.

The necessity of a spacefaring mythology for a spacefaring civilization offers a key to a problem posed earlier. In section 3 we asked three questions, based on the assumption that the necessary condition for a spacefaring breakout was the existence of a space-capable civilization:

• What could constitute a sufficient condition of an early spacefaring inflection point?

• What could constitute a sufficient condition of a mediocre spacefaring inflection point?

• What could constitute a sufficient condition of a late spacefaring inflection point?

Perhaps the sufficient condition of a spacefaring breakout is an adequate mythology that can inspire, contain, and direct the unprecedented changes that would fall to the human condition in the event of a spacefaring breakout and the transition to a spacefaring civilization. The industrial revolution transformed our way of life, and gave us powers that no one from earlier eras of human history would ever have believed would come to be held by human beings. A spacefaring breakout would be similarly disruptive—different in every detail, but ultimately no less transformative of social institutions and the context of the ordinary business of life.

Mythology takes shape over the longue durée, or over historical time periods longer than the longue durée, and the materials it draws upon are far older. If this is an adequate way to understand the human condition, i.e., historically, over evolutionary time, and if it is also true that mythology takes shape only over the longue durée, then it would appear to be the case that only a late spacefaring inflection point would allow a mythology to come into being that would be adequate as a central project for a spacefaring civilization (assuming that such a mythology is not already in existence, or something close enough to being such a mythology, but waiting in the wings to be exapted for spacefaring).

We could posit, as a counterfactual to our own civilization, another civilization in which the mythologies available during the historical period in which space exploration technologies first become available are suited for a spacefaring breakout, and this serves as the sufficient condition above and beyond the necessary condition of being space-capable. In this scenario, an early spacefaring breakout obtains, and this answers the first of our three questions, though given these assumptions the sufficient condition must subsist in the space-capable civilization.

At one remove from this scenario would be a civilization in which the mythic materials are available in the wider culture, and they merely await some individual or institution to tie together the technologies and the mythic materials into a whole. In this scenario, several conjunctures follow upon the equivalent of a Founding Era in which the mythic material is rapidly adapted to space exploration, and a mediocre spacefaring breakout obtains, which answers our second question.

Where there remains an unbridgeable gulf between the introduction of space exploration technologies and a mythology adequate to their exploitation, such a mythology must develop over a formative period measured over a longue durée, as nothing less would be sufficient for the codification of a mythology on such a scale where none existed previously. This appears to be a chicken-and-egg problem, as we cannot build human experience in space without being in space, and we can’t be in space without the human experience of space exploration. This chicken-and-egg scenario leaves open the window for a very gradual adaptation to spacefaring—so incremental that its effects cannot be discerned over ordinary historical scales of time, but which, looking back over a longue durée, might be obvious in hindsight. The slowness of this incremental process is also the reason for the period of time required for such a mythology to come into being.

13. The Weston Principle

Mythologies come into being over scales of time that are nearly incomprehensible to the individual human being, and because of this we have often—more often than not—misunderstood the mythologies by which we live. We do not know the histories of our mythologies, because these histories are lost in the mists of time, and it is only in relatively recent scholarship that a sustained effort has been made to uncover the origins of stories so close to the human heart that we cannot see them objectively without the greatest effort.

Jessie L. Weston published From Ritual To Romance a hundred years ago in 1920. Weston’s book traced elements of the Arthurian mythology and the Grail legend to pre-Christian sources. Arthurian mythology constitutes a significant corpus of medieval literature, deeply Christian in its symbols and motifs, but the wealth of detail on display in the Arthurian tradition cannot be exhausted by distinctively Christian ideas. Weston’s research supplied the origins of the non-Christian remainder of the Arthurian tradition from earlier and older mythology. In its time Weston’s thesis was controversial much as Frazer’s The Golden Bough, a major influence on Weston, had been controversial. We are no longer shocked by such scholarship.

The principle by which Weston worked can be generalized beyond the specific circumstances of Arthurian mythology supervening upon the mythology of early agricultural societies such as described in Frazer’s The Golden Bough. The mythology of such societies as described by Frazer would have, in turn, been indebted to the earlier mythologies of their predecessor societies, perhaps dominated by intensive gathering and transhumance, and the mythology of these societies would in their own turn have been indebted to yet earlier mythologies of hunter-gatherers, such as we possess a mute record in cave paintings and prehistoric sculpture. And just as past mythologies owed part of their substance to previous mythologies, any future mythology will owe part of its substance to mythologies represented in the present and earlier. I call this the Weston Principle.

Our records of past mythology are significant only up to five thousand years ago, when written language appeared, and before that our evidence is only indirect, if it exists at all. From Çatalhöyük (during the Holocene, from about 9,500 to 7,700 years before present) we have many intriguing paintings and sculptures exhibiting a thematic unity—bulls, aurochs, and corpulent Venus figurines—but, lacking written records, any reconstruction of the belief system of which they are the material expression, can only be speculative. Further excavation may reveal additional evidence, but we have no reason to expect finding the Anatolian equivalent to The Epic of Gilgamesh, as there is no evidence at all for written language during the time of Çatalhöyük.

Before Çatalhöyük we have the remarkable cave art of the Paleolithic, itself a period of prehistory extending over more than three million years and consisting of a succession of cultures, each of which may have had their own mythology, received from a processor and passed down to a successor culture, with descent with modification at each stage of transmission. Over this long succession of hunter-gatherer Paleolithic cultures one suspects that the mythology remained relatively simple as long as social organization remained relatively simple, but that development accelerated with the advent of cities, complex social organization, and eventually written language. We arrive at length at the depth and complexity of something like the Arthurian tradition by the accumulated mythological development of successive human societies extending back in deep time.

Record-keeping technologies introduce an asymmetry into history. First language, then written language, then printed books, and so and so forth. Should human history extend as far into the deep future as it now extends into the deep past, the documentary evidence of past beliefs will be a daunting archive, but in an archive so vast there would be a superfluity of resources to trace the development of human mythologies in a way that we cannot now trace them in our past. We are today creating that archive by inventing the technologies that allow us to preserve an ever-greater proportion of our activities in a way that can be transmitted to our posterity.

The Weston Principle connects these mythologies through time based on an evolutionary sequence in which each stage of development is indebted to the stage that preceded it, and no stage of development begins as a blank slate.

14. The Beginning of the Inquiry

We are, as human beings, adrift without an adequate mythology—where there is no vision, the people perish. The institutions of human life—what Braudel called the structures of everyday life — are no less subject to institutional drift than industries, scientific research programs, and civilizations, though in the absence of more sophisticated social organization, the institutions of human life are ultimately reducible to subsistence. Indeed, a reduction to subsistence is what awaits us if we allow our institutions to drift downward to their lowest common denominator.

Assuming that we wish to avoid a reduction to subsistence, which is social collapse, it is in our interest to cultivate some mythology that will allow us to retain some of the gains that we have made upon mere subsistence, and, if possible, perhaps also to better these gains and to transcend our present condition in favor of a stage of social development as far removed from the present as the present is removed from bare subsistence. But mythology cannot be fabricated on demand; a mythology is organic to the life of a people, or it is not a mythology (perhaps this is the proper demarcation between mythology and ideology).

A spacefaring mythology would be organic to the life of a spacefaring people. Mythologization, including spacefaring mythologization, is a process that occurs over the longue durée (section 12), incorporates material from the deep past of humanity (section 11), and must shape itself to the most recent cultural forms that are its immediate predecessors (section 10). These general principles are some of our clues that point us in the direction of some future spacefaring mythology.

We cannot yet say what a spacefaring mythology would be, but we can make a systematic inquiry into the forms of human experience that will eventually be represented within a spacefaring mythology—the full range of human experiences become lived experience in outer space, and, from that lived experience in outer space, become the raw material to be shaped into mythic forms. This, then, is not the end of the inquiry, but the beginning.

Notes

[1] Carl Sagan, Cosmos, New York: Random House, 1980, Chapter 1, p. 5.

[2] What I am here calling the “Founding Era” Michael J. Neufeld has called the “Heroic Era” in the book he edited, Spacefarers: Images of Astronauts and Cosmonauts in the Heroic Era of Spaceflight (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press, 2013): “The missions of the first astronauts and cosmonauts opened a period I call ‘the heroic era’ of human spaceflight—both for the media representation of their image and the actual danger of their occupation.” Neufeld reckons the Heroic Era from Gagarin’s 1961 flight to the 1986 Challenger disaster, so his Heroic Era is a little offset from, and a little longer than, the Founding Era as I define it.

[3] I have slightly revised the wording of these inflection points since I introduced them in The Spacefaring Inflection Point.

[4] If human civilization had transitioned into an early spacefaring breakout, with no lapse in the continuity of spacefaring developments, we would by now be more than sixty (60) years into this historical process of becoming a spacefaring civilization. For an historical parallel, if we take the origin of the industrial revolution to be James Watt’s steam engine (commercially introduced in 1776), the continuity of development of the industrial revolution meant that sixty years later we come to a time when railroads were being built and the telegraph was being invented. If the industrial revolution had entered into a period of stagnancy after fifteen years, there would have been no railroads in the 1830s.

[5] Eleni Panagiotarakou, “Agonal Conflict and Space Exploration,” chapter 47 in The Ethics of Space Exploration, edited by James S.J. Schwartz and Tony Milligan, London: Springer International Publishing, 2016.

[6] “I am afraid that it is from baser motives that Governments are willing to spend the enormous sums involved in making space-travel possible.” Quoted in Earth to Russell by Chad Trainer. While Russell never withheld his disdain for the Space Race, in other contexts he was more willing to consider a spacefaring far future for humanity; cf. Bertrand Russell and Olaf Stapledon.

[7] In psychodynamic psychology, the idea of sublimation is that otherwise destructive energies are channeled into some other part of life, often expressed constructively in art or science or invention. Sublimation on a trans-personal level, the sublimation of the worst instincts of the crowd, can also channel otherwise destructive energies into creative projects, and it is this that accounts for the great monuments of civilization such as the pyramids, the Parthenon, the Taj Mahal, the LHC, ITER, and the ISS.

[8] Clark, Kenneth, Civilisation, Chapter 5, “The Hero as Artist,” p. 120. Later in the same book Clark wrote, as if to hammer home his earlier point, “The dazzling summit of human achievement represented by Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo da Vinci lasted for less than twenty years.” (p. 139) And again, regarding the impressionists: “…it is surprising how short a time the movement, as a movement, lasted. The periods in which men can work together happily inspired by a single aim last only a short time—it’s one of the tragedies of civilisation.” (p. 290) It would be instructive to compare computer technology to spacefaring technology, as computer technology seems to have experienced nearly continuous development over several decades—still perhaps within a charitable interpretation of Clark’s window of achievement, but four times as long as the Founding Era. Also instructive is a comparison with nuclear technologies, though in the case of nuclear technologies we know that their stagnation was the result of both proliferation concerns and public discomfort with nuclear power.

[9] Clark’s Civilisation television series, like the book of the same title, was first broadcast in 1969—the same year in which the Apollo Program succeeded in landing human beings on the moon and returning them safely to Earth. Since Clark focused on art and society rather than science and technology, his examples are mostly drawn from traditional humanistic studies of civilization rather than technical studies of civilization, but Clark’s point could be argued either way.

[10] For one superficial example, the total cost of the Voyager Program from 1972 to 1989 was 865 million dollars (51 million dollars per year, on average); the cost to operate the LHC is about a billion dollars per year. This is not a criticism of large particle accelerators, only a comparison of costs. Also, the Voyager costs have not been adjusted for inflation, which one would need to factor in for an apples-to-apples comparison.

[11] The arguments that highlight a simple-minded and ultimately self-defeating distinction between human space exploration and robotic space exploration have led to an artificial debate about whether space exploration funds should be spent on human missions or robotic missions. The debate is artificial because, if our space program had not entered into a state of institutional drift, and if a vigorous space program had tumbled forward into an early inflection point for spacefaring civilization, then the scientific instruments we would have been able to build in space would have far exceeded capacities of the scientific instruments we have sent out with robotic space exploration missions, and cosmology would have become “big science,” so integrated with the central project of spacefaring civilization that it would be virtually indistinguishable from that civilization itself.

[12] In this connection I am reminded of the famous claim that the British acquired their overseas empire in a fit of absence of mind (“We seem, as it were, to have conquered and peopled half the world in a fit of absence of mind.” John Robert Seeley, The Expansion of England, 1883); one might contrariwise claim that we have failed to converge upon a spacefaring civilization in a fit of absence of mind. No one, single decision led us to our present condition, and no conscious choice was made not to pursue the space exploration vision. In the present context I am choosing to employ a strong formulation of our failure to attain spacefaring civilization, largely in order to avoid any ambiguity on the topic. A full discussion of this point would constitute the matter for another essay.

[13] Fernand Braudel, The Perspective of the World (Civilization and Capitalism, Vol. III), p. 17. Both Hegel and Nietzsche, incidentally, also distinguished three kinds of history, but these were not distinct time-scales of history, as in Braudel, but, rather, they were kinds of historiography. I have previously discussed Braudel in my Centauri Dreams post Synchrony in Outer Space. I hope to discuss Hegel and Nietzsche in relation to the historiography of spacefaring civilizations in a future essay.

[14] Fernand Braudel, The Identity of France, Vol. I, New York: Harper & Row, 1988, p. 408.

[15] Fernand Braudel, A History of Civilizations, Penguin Books, 1993, p. xxiv.

[16] Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, Volume 2, Part Three: Event, Politics and People, p. 901.

[17] Fernand Braudel, On History, “History and the Social Sciences,” University of Chicago Press, 1980, p. 27.

[18] White, Frank, The Overview Effect: Space Exploration and Human Evolution, third edition, Reston, VA: AIAA, 2014, p. 3. My use of “central project” differs somewhat from White’s use as I have sought to develop the idea in relation to the institutional structure of civilization. However, it was in White’s book that I first encountered the idea, so my use of it is related to White’s use by descent with modification. Some of my posts about the central projects of civilizations include Civilizations and Central Projects, An Anecdote about the Unifying Role of Central Projects, Central Projects and Axialization, Some Desultory Theses on the Central Project of Contemporary Civilization, and The Central Project of Properly Scientific Civilizations, inter alia. What I have not yet done is to write an explicit and systematic exposition of central projects, or to generalize the idea of a central project to other institutions beyond the institution of civilization.

[19] John M. Logsdon argued that there was no Sputnik Crisis: “It was a ‘Gagarin moment’ rather than a ‘Sputnik moment’ that precipitated massive government support for the technological innovations needed for success in space.” (Logsdon, John M., “John F. Kennedy’s Space Legacy and Its Lessons for Today,” Issues in Science and Technology, Vol. 27, No. 3, Spring 2011, pp. 29.) We will have occasion to further consider Logsdon’s paper in what follows.

[20] Excerpt from the ‘Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs’ President John F. Kennedy, Delivered in person before a joint session of Congress May 25, 1961.

[21] John F. Kennedy Moon Speech – Rice Stadium, September 12, 1962. Both speeches are well worth reading in their entirety.

[22] Logsdon, John M., “John F. Kennedy’s Space Legacy and Its Lessons for Today,” Issues in Science and Technology, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Spring 2011), pp. 29-34.

[23] I don’t want to make it sound like the pursuit of von Braun’s vision would have been a cake walk. A mission as complex as von Braun’s Mars mission would have almost certainly resulted in some failures and fatalities, though if the will had been present to carry out a plan this ambitious, the mission would have continued despite fatalities, as indeed the Apollo Program continued despite the fatalities of Apollo 1, and even fulfilled Kennedy’s Lunar landing timetable despite the setback to the program. When space shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after launch, killing all aboard, the Space Shuttle program was suspended for almost three years.

[24] David S. F. Portree’s blog Spaceflight History: a history of spaceflight told through missions & programs that didn’t happen has an excellent treatment of the IPP: Think Big: A 1970 Flight Schedule for NASA’s 1969 Integrated Program Plan.